In a little-noticed move last week, Israeli defence minister Avigdor Lieberman barred an official close to Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas from entering Israel. Mohammed Madani is accused of “subversive activity” and “political terror”.

His crimes, as defined by Lieberman, are worth pondering. They suggest that Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians is rooted less in security issues and more in European colonialism.

In his role as chair of the Palestinian committee for interaction with Israeli society, Madani had understandably used his visits to Israel to meet Israeli Jews – but he chose the wrong kind.

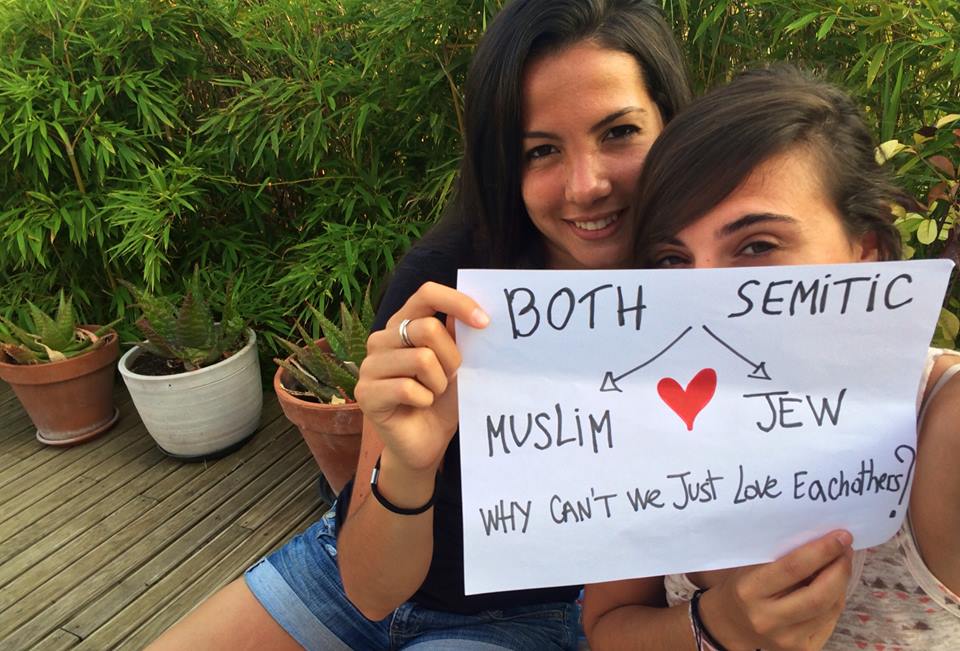

He tried to open a dialogue with what are known in Israel as Mizrahim, Israelis descended from the Jews who emigrated from Arab states following Israel’s creation in 1948. Today these Arab Jews comprise about half of Israel’s population. Abbas is known to be keen to forge ties with them.

Most of the country’s rulers identify as European Jews, or Ashkenazim. From the outset, this European elite distrusted the Arab Jews, seeing them as a “backward” population that might undermine Israel’s claim to be an outpost in the Middle East of the “civilised” west.

But more specifically the Ashkenazim feared that one day the Arab Jews might make a political alliance with the native population, the Palestinians. Then the Ashkenazim would be outnumbered. The Mizrahim, who came from countries as diverse as Morocco and Iraq, had a lot more in common with Palestinians than they did with the recently arrived Europeans.

Originally, Israel’s founders had intended not to include the Arab Jews in their nation-building project. They were forced to reconsider only because Hitler’s genocide in Europe deprived them of sufficient numbers of “civilised” Jews.

The archives reveal that Israel engineered much of the migration of Arab Jews, inducing them with false promises or conducting false-flag operations to foment suspicion of them in their home countries. They were seen as a useful cheap labour force, to replace the Palestinians who had been expelled.

David Ben Gurion, a Pole who became the first prime minister, described the Mizrahim in exclusively negative terms, as a “rabble” and “human dust”. They were a “generation of the desert”. Mizrahi immigrants were subjected to a programme of “de-Arabisation”, their presumed backwardness treated no differently from the diseases they supposedly carried. They were smothered in DDT on the flights to Israel.

Documents show the army vigorously debating whether their new Arab Jewish conscripts were mentally retarded, making them a lost cause, or simply primitive, a condition that might be uprooted over time.

Israel’s struggle, according to Ben Gurion, was to “fight against the spirit of the Levant that corrupts individuals and society … We do not want the Israelis to become Arabs”.

That task was made harder because, despite an aggressive expulsion campaign in 1948, Israel still included a significant population of Palestinians who had become citizens.

Israel kept them apart from the Mizrahim through segregation – separate communities and education systems. Mizrahi children were forbidden to speak Arabic in their Jewish schools, and made to feel ashamed of their parents’ benighted ways.

There were always those who resisted the negative stereotypes. In the 1970s some even set up a local chapter of the Black Panthers, named after the militant African-American group in the United States and echoing its demands for revolutionary change.

Today, that is ancient history. A small number of Mizrahim have joined the Democratic Rainbow, which focuses on social justice for Arab Jews. Others have sought solace in religious fundamentalism.

Yet more have internalised the self-hatred cultivated for them by the state. Many now vote for the far-right, including Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party, the official rival to the Labour party’s founding fathers.

The Likud’s zealously anti-Palestinian platform has proved appealing. Netanyahu’s warning on election eve that the “Arabs are coming out to vote in droves” rallied Mizrahi voters to Likud’s side and probably returned it to power.

Palestinian-hating Mizrahim can be seen each weekend in the stands at Jerusalem’s main football club, chanting “Death to the Arabs”.

One of their number, Elor Azaria, an Israeli soldier-medic, put the fans’ slogan into practice. In March he was caught on camera executing a Palestinian as he lay wounded on a street in Hebron. Netanyahu and Lieberman have offered him their backing.

More “moderate” Ashkenazis, including the army command, meanwhile, have distanced themselves from Azaria, fearing the damage his very public actions could do to Israel’s “western” credentials.

But their loathing of everything Arab is no less intense than the country’s founders.

Last week a group of former army generals and Ashkenazi politicians who support a two-state solution issued a video. It imagined the “nightmare scenario” of Palestinians putting down their weapons and heading to the polls to elect one of their own as Jerusalem’s mayor.

It was precisely this kind of “political terror” that led Lieberman to ban Madani from Israel last week. With the Arab Jews on the Palestinians’ side, the conflict with Israel might be ended at the ballot box. Now that truly would be subversive.

A version of this article first appeared in the National, Abu Dhabi.

Jonathan Cook won the Martha Gellhorn Special Prize for Journalism. His latest books are “Israel and the Clash of Civilisations: Iraq, Iran and the Plan to Remake the Middle East” (Pluto Press) and “Disappearing Palestine: Israel’s Experiments in Human Despair” (Zed Books). His website is www.jonathan-cook.net.