An interview with MuslimPress

Why did you choose the name “Jatiindia” for your work? What’s the significance of this name?

Inequality exists in societies all across the globe. Designed by Brahmanism (which came before Hinduism), the caste system is a uniquely cruel and immutable version of this phenomenon because it has been conveniently sanctioned by the Hindu religion.

The Indian word for caste is jati, the roots of which an be traced to Hinduism’s four-varna system or varnashrama dharma as prescribed by Hindu scripture, and structured in an hierarchy of occupations with the brahmins on the top, followed by kshatriyas, vaishyas, and shudras — in that order.

Outside of this system, you will find the country’s Adivasis, India’s original inhabitants, its indigenous communities; as well as Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) — literally meaning broken, crushed people — who today are low-paid farm hands and contract laborers.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar described the workings of the caste system best when he said that it “is not merely a division of labor. It is also a division of laborers.” Himself a Dalit, Ambedkar (1891-1956) was the principal architect of the Indian Constitution, and his main focus was the emancipation of his Dalit brothers and sisters.

Over the millennia, within the four-varna system there proliferated thousands of castes and subcastes, or jatis. They are intended to be distinct gene pools, with intercaste marriage frowned upon. Caste now burdens not only the Hindu population. It has proliferated throughout India’s cultural as well as biological DNA, even into the country’s practice of Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and Sikhism. Each community has its own specific norms, all of which employ caste-style hierarchies of their own.

There would be no functioning—or shall we say dysfunctioning—India without this worst form of social exclusion in the world. So I thought why not just come right out and prefix jati to India and call it Jatiindia, i.e., the land of jatis. After all, jati/caste fundamentalism not only has survived in modern times, it is thriving more than ever under technologically sophisticated, neo-liberal fundamentalism.

People in the West like to think of India as this great land of psychedelic spirituality that introduced Gandhi and the spirit of non-violence to the world. That’s such a farce because the country’s own backyard is a landscape littered with systemic cultural violence.

I think of the caste system as a kind of racism pumped up on religio-capitalist steroids. Hence, the title for this series, Jatiindia.

How did you decide to create this piece?

The murder of Rohith Vemula prompted this series. Rohith was the 26-year-old son of a landless Dalit mother who hanged himself in a student hostel room on January 17th, 2016. Many in India have referred to his death as murder, because it encapsulates the continuing struggle confronting a cross-section of the country’s oppressed.

According to writer and democratic-rights activist Anand Teltumbde, “The reason [for suicides of Dalit scholars (like Rohith) driven by caste atrocities] can be traced to the social Darwinist ethos of neoliberalism which reversed the welfarist paradigm created by Keynesian economics. Its social implications contra-intuitively resonate with the upsurge of Hindutva forces in the country, evidenced by the BJP’s rise from a marginal position in the 1980s to be the contender for political power at the center….The strategy of the Hindutva camp is to brahmanize common folks of the dalits and to demonize the radical dalits. As dissenting Muslim youth are branded terrorist, dalit-adivasi youth are being stamped as extremists, casteist and anti-nationals.”

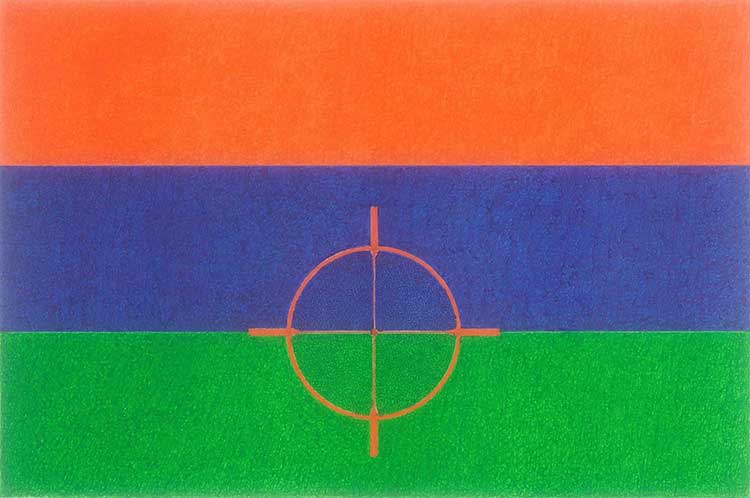

The generic title for this series is Jatiindia: A Flag of Atrocities Caste, Present and Future. And each issue addressed within this series has its own subheading.

The work attempts to bring forward some of the targeted faces of resistance who have challenged the stagnant ideology of exclusion in India (often referred to as “the world’s largest democracy” but in my mind the world’s largest hypocrisy): Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims, Christians, occupied Kashmiris, India’s northeasterners, and others who have been caught for ages between the old and the ever-mutating new—between the dogmas of religious scripture and the terrorism of the state.

The forces of these dogmas have usurped not only the souls and the humanity of so, so many people, but also their land, their rivers, their mountains, their livelihoods from under their feet. Biodiversity has been replaced with exploitation diversity.

In conjunction with Indian prime minister Narendra Modi’s visit in Washington with President Barack Obama in September 2014, the Washington Post published a jointly written opinion piece by the two world leaders titled A renewed U.S.-India partnership for the 21st century. Here’s part of what they had to say: “We will discuss ways in which our businesses, scientists and governments can partner as India works to improve the quality, reliability and availability of basic services….An immediate area of concrete support is the ‘Clean India’ campaign, where we will leverage private and civil society innovation, expertise and technology to improve sanitation and hygiene throughout India….Forward together we go — chalein saath saath.” Really? All that’s good, but shouldn’t Jatiindia first flush out the systemic and centuries-old clogged up caste system and its ensuing atrocities before the two country’s elites can move “forward saath saath”?

This is what Ambedkar, author of Annihilation of Caste, was talking about when he said that caste is “not merely a division of labor. It is also a division of laborers.” In India, bais (housemaids), who, besides sweeping and swabbing upper-caste homes also clean the toilets seven days a week. Most of them don’t have a toilet in their own one-room homes, but have a common one that many families share. I asked one such toilet-cleaning bai, “Who comes to clean the toilets in the chawl (slum) where you live?” She replied, “The bhangi (manual sewage scavenger).” There is a very tightly organized hierarchy of filth. An upper-caste-led “Clean India” campaign for the 21st century is doomed without the annihilation of caste itself and the end of the ideology of layering servants upon servants upon servants.

What does each color that you used in the flag symbolize?

The orange of the top bar symbolizes long-existing casteism, now made more open and feverish by resurgent Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) politics. Blue—a color historically adopted by the Dalit movement—here honors all of India’s oppressed people, including the occupied people of Kashmir. The bottom green bar symbolizes India’s ecological foundations, which are endangered by the ideology of neoliberalism and defended by our Adivasis and other oppressed people, including Kashmiris. The circular image (which I put in its usual place in the center of the flag in earlier versions) is positioned equally over the blue and green bars to signify a target viewed through a weapon’s saffron crosshairs.

This latest in my series, titled Now You Don’t See Me, Now You Don’t,is about the Indian occupation of Kashmir. The three pen &ink drawings that accompany this work includes a portrait of Afzal Guru’s wife and son represented as Jatiindia: A Flag of Atrocities Caste, a portrait of a pellet gun victim represented as Jatiindia….Present, and the blank crosshairs image as Future.

How do you see the situation in Kashmir?

It’s similar in a sense to the situation in Palestine, arising as it does from an arbitrary partition of territory by colonial powers. But it’s different in that most people know very little about Kashmir, while much more has been said and written about Palestine over the past half-century. As Amy Goodman of Democracy Now commented back in March 2010, “Most people here [people in the West] know it as a sweater. That’s what they think of when they hear ‘Kashmir.’” That’s how far away the plight of Kashmiris is from the conscience of the so-called “international community.”

The push for self-determination in Kashmir goes back, in fact, to the same time period as the creation of Israel, to 1947, India’s independence from British rule, and the subsequent partition of India and Pakistan. Following the partition, a plebiscite was supposed to be held to determine the fate of Jammu and Kashmir. That never happened, and things snowballed from there.

Next year will mark the 50th anniversary of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank including East Jerusalem and Gaza. Norman Finkelstein said recently, “Roughly speaking, two and a half generations of Israelis have lived with…. [and] at this point has been an active participation in a quiet brutal occupation.” As we all know, some of that desensitization of a population that Finkelstein is talking about has something to do with the fact that service in the IDF is mandatory for every Israeli citizen 18 years and older (with some exceptions).

On the other hand, upper-caste Indians’ occupation of the hearts, hands, minds, bodies, lands, waters, of some of their own people — Dalits, Adivasis, Muslims, and others, goes back many, many generations, and so does their desensitization which manifests itself in the form of absolute silence, to the inherently atrocious workings of the state machinery and the Indian population in general.

The military occupation of Kashmir, like the Israeli occupation of Palestine, translates to the active participation of the occupying population keeping silent on atrocities being committed on a daily basis by “security” forces, and the use of various forms of collective punishment.

Many refer to the summer of 2010 as the Kashmiri Intifada, with the sang-bazan (stone-pelters) storming the streets of Srinagar.

How has the government affected the daily lives of the Kashmiri people?

Stuck between a rock and a hard place — nuclear-powered India and nuclear-powered Pakistan — Indian-administered Kashmir (Kashmir, Jammu, Ladakh) is the most densely militarized zone in the world.

The fight turned into an armed struggle in the early 90s. In a 1994 resolution, Kashmir was declared an ‘integral part’ of India. Since then the Muslim-majority Kashmir valley with a population of over 12,500,000 has been saturated with close to 700,000 military and paramilitary forces (one state-armed person for every seventeen Kashmiris) dictating law and order and thereby controlling every movement of every Kashmiri.

India’s objective is to integrate the region into its territory by any means possible. According to Buried Evidece, a report put out by the International People’s Tribunal on Human Rights and Justice in Indian-Administered Kashmir, the tactics of integration include “the domestication of Kashmiri people through the selective use of discipline and death as regulatory mechanisms. Discipline is affected through military presence, surveillance, punishment and fear. Death is disbursed through ‘extra-judicial’ means, and those authorized by law….Official state discourse conflates cross-border militancy with present nonviolent struggles by local Kashmiri groups for political and territorial self-determination, portraying local resistance as “terrorist” activity.”

The report further states that, “In Kashmir, between 1989-2009, the actions of the military and para-military forces have resulted in [more than] 8,000 enforced disappearances and [more than] 70,000 deaths, including through extra-judicial or ‘fake-encounter’ executions, custodial brutality, and other means. [The report also documents] 2,700 unknown, unmarked, and mass graves containing [more than] 2,943 bodies, across 55 villages in Bandipora, Baramulla, and Kupwara districts of Kashmir.”

The years 2002/2003 witnessed a crushing of the armed rebellion in Kashmir. But what remained, among other horrors, was the Indian Parliament’s draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), the Public Safety Act (PSA), streets lined with heavily armed soldiers, traffic policemen with AK 47s, armored vehicles, mass rapes, torture centers, economic and social hardships, arbitrary detentions, hospitals overcrowded with patients suffering from multiple bullet wounds, many teenagers among dead and severely wounded, psychological problems, graveyards crowded with victims of conflict, shutdowns of the internet and mobile services, and the crackdown on newspapers.

What replaced the armed insurgency was a less violent form of rebellion. Many incidents sparked fresh non-violent mass protests in the region, including thousands of protesters taking to the streets in mid-2008 when the government decided to grant 100 acres of land to the Hindu shrine of Shri Amaranth in the Kashmir Himalayas; then an incident in May 2009 when two young women were found dead in Sophian, south Srinagar, their families alleging that that they had been abducted, raped and murdered by troops; the January 2010 killing of a schoolboy in Srinagar by Border Security Force (BSF) soldiers; and the April killing of three innocent civilians in Machil by the Indian Army. Each killing triggered more protests, triggering more killings. The cycle has continued. During these protests, many thousands of stone pelters have taken to the streets, with security forces answering back with gunfire.

Does the situation in Kashmir receive enough media attention?

The latest uprising was sparked by the killing of 21-year-old Hizbul Mujahideen commanderBurhan Wani on July 8th this year. Scores of people have since been killed and hundreds of others maimed, disfigured, and blinded by pellet guns, an innovation introduced by the Indian Army as a “non-lethal” crowd-control measure. The mainstream media has not given this kind of news the attention it deserves.

All along, the media have been silent about the atrocities the Indian military has inflicted on the people of Kashmir. Unlike other issues (such as the ongoing conflict in Manipur, on which the media are completely silent), this conflict has attracted a lot of media. But the reports are all hogwash. Real Kashmiris have no presence in the Indian media.

Take the case of Afzal Guru who was one of the suspects in the attack on the Indian Parliament in December 2001. He was an innocent Kashmiri hanged for a crime he did not commit.

Arundhati Roy wrote, “A fresh media campaign began…. ‘Afzal Guru was one of the terrorists who stormed parliament house on 13 December 2001. He was the first to open fire on security personnel, apparently killing three of the six who died.’ Even the police charge sheet did not accuse Afzal of that. The supreme court judgment acknowledged the evidence was circumstantial: ‘As is the case with most conspiracies, there is and could be no evidence amounting to criminal conspiracy.’ But then, shockingly, it went on to say: ‘The incident, which resulted in heavy casualties, had shaken the entire nation, and the collective conscience of society will only be satisfied if capital punishment is awarded to the offender.’”

And the media lies continue today.

What do you see as the major force behind these conflicts?

The people of Kashmir have demonstrated time and time again that they want nothing short of Azadi (freedom) from occupation. That’s what they’re fearlessly running toward, stones in hand, in the crosshairs of the Indian security forces, chanting “Hum Kya Chahte (What do we want)? Azadi (Freedom).”

Priti Gulati Cox (@PritiGCox) is an interdisciplinary artist and a local coordinator for the peace and justice organization CODEPINK. She lives in Salina, Kansas, and can be reached at[email protected]. Visitcaste, capitalism, climateto see more of her work.