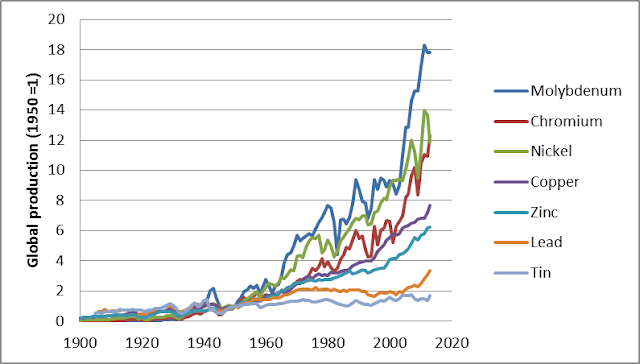

Molybdenum is essential for the manufacture of high-grade stainless steels, but at present molybdenum is hardly recycled. Yet unless reuse of molybdenum is dramatically increased, the extractable reserves of molybdenum on Earth will run out in about eighty years from now. The extractable reserves of antimony, a mineral used to make plastics more heat-resistant, will run out within thirty years.During more than a century the use of mineral resources increased exponentially with an average between 3 and 4% annually. Can this go on, given the limited amounts of mineral resources in the earth’s crust?

TOP TEN SCARCE MINERAL RESOURCES

|

Exhaustion period (in years) of remaining extractable mineral resources

|

Important applications

|

|

|

Antimony

|

30

|

Flame retardants

|

|

Gold

|

40

|

Electronic components

|

|

Zinc

|

80

|

Corrosion protection

|

|

Molybdenum

|

80

|

High-grade steels

|

|

Rhenium

|

100

|

High-quality alloys

|

|

Copper

|

200

|

Electricity grid

|

|

Chromium

|

200

|

Stainless steels

|

|

Bismuth

|

200

|

Pharmaceuticals and cosmetics

|

|

Boron

|

200

|

Glasswool

|

|

Tin

|

300

|

Tins, brass

|

What is a sustainable extraction rate?

In my dissertation I have defined a sustainable extraction rate as follows: “The extraction of a mineral resource is sustainable, if a world population of nine billion people can be provided with that mineral resource during a period of thousand years, supposing that the average use per world citizen is equally divided over the countries of the world”. Actually, the concept of sustainability is only applicable to an activity, which can continue forever. Concerning the extraction of mineral resources, I consider a thousand years as a reasonable approach. This is arbitrary of course. But 100 years is too short. In that case we would accept that our grandchildren would be confronted with exhausted mineral resources.

A sensitivity analysis reveals that even if we assume that the extractable reserves in the Earth’s crust are ten times higher than the already optimistic assumption of the UNEP International Resource Panel, then the use of antimony, gold, zinc, molybdenum, and rhenium in industrialized countries would still have to be hugely reduced in order to preserve sufficient of these raw materials for future generations. This is particularly so if we want these resources to be more fairly shared among countries and people than is currently the case. There are also environmental and energy limits to the ever deeper and remoter search for ever lower concentrations of minerals. If we want to stretch out all the exhaustion periods in the table to 1000 years, then it can be calculated that the extraction of antimony should be reduced of 96 %, that of zinc of 82 %, that of molybdenum of 81 %, that of copper of 63 %, that of chromium of 57 % and that of boron of 44 %. This is compared to the extracted quantities in 2010. These reduction percentages are high. The question is whether that is feasible. Moreover, would the price mechanism not lead to a timely and sufficient extraction reduction of scarce mineral resources?

The price mechanism fails

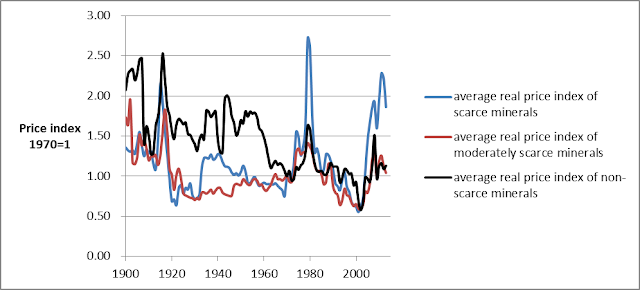

One would suppose that the general price mechanism would work: the price of relatively scarce mineral resource rises quicker than the price of relative abundant mineral resources.

TRENDS IN THE REAL PRICE OF SCARCE AND NON-SCARCE MINERALS IN THE UNITED STATES 1900-2015*

* The minerals have been classified according to their scarcity. The scarce raw materials in the figure are antimony, zinc, gold, molybdenum and rhenium. The moderately scarce raw materials are tin, chromium, copper, lead, boron, arsenic, iron, nickel, silver, cadmium, tungsten and bismuth. The non-scarce raw minerals are aluminum, magnesium, manganese, cobalt, barium, selenium, beryllium, vanadium, strontium, lithium, gallium, germanium, niobium, the platinum-group metals, tantalum and mercury.My research makes clear that the price of scarce mineral resources has not risen significantly faster than that of abundant minerals. I demonstrate in my dissertation that, so far, the geological scarcity of minerals has not affected their price trends. The explanation might be that the London Metal Exchange looks ahead for a maximum period of only ten years and that mining companies anticipate for up to thirty years. But we must look much further ahead if we are to preserve scarce resources for future generations.

Eventually, the price of the scarcest minerals will rise, but probably not until their reserves are almost exhausted and little remains for future generations.

Technological opportunities are not being exploited

Are the conclusions I reach over-pessimistic? After all, when the situation becomes dire, we can expect recycling and material efficiency to increase. The recycling of molybdenum can be greatly improved by selectively dismantling appliances, improved sorting of scrap metal and by designing products from which molybdenum can be easier recycled. Alternative materials with the same properties as scarce minerals can be developed. Antimony as a flame retardant can be replaced fairly easily by other flame retardants. Scarcity will drive innovation.

Thirty to fifty percent of zinc is already being recycled from end of life products, but although it is technologically possible to increase this percentage, this is barely happening. Almost no molybdenum is recycled. Recycling is not increasing because the price mechanism is not working for scarce minerals. In the absence of sufficient financial market pressure, how can technological solutions for recycling and substitution be stimulated?

What should happen?

I argue that what is needed is an international agreement: by limiting the extraction of scarce minerals stepwise, scarcity will be artificially increased – in effect, simulating exhaustion and unleashing market forces. This could be done by determining an annual extraction quota, beginning with the scarcest minerals. Such an international mineral resources agreement should secure the sustainable extraction of scarce resources and the legitimate right of future generations to a fair share of these raw materials. This means that agreement should be reached on reducing the extraction of scarce mineral resources, from 96 percent for antimony to 82 percent for zinc and 44 percent for boron, compared to the use of these minerals in 2010. In effect, such an agreement would entail putting into practice the normative principles that were agreed on long ago relating to the sustainable use of non-renewable raw materials, such as the Stockholm Declaration (United Nations, 1972), the World Charter for Nature (UN, 1982), and the Earth Charter (UNESCO, 2000). These sustainability principles were recently reconfirmed in the implementation report of Agenda 21 for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2016).

Financial compensation for countries with mineral resources

Countries that export the scarce minerals will be reluctant to voluntarily cut back extraction because they would lose revenue. They should therefore receive financial compensation. The compensation scheme should ensure that the income of the resource countries does not suffer. In exchange, user countries will become owners of the raw materials that are not extracted, but remain in the ground. An international supervisory body should be set up for inspection, monitoring, evaluation and research.

Not a utopian idea

In my dissertation, I set out the case for operationalizing the fundamental principles for sustainable extraction of raw materials, which have been agreed in various international conferences and confirmed by successive conferences of the United Nations. The climate agreement, initially thought to be a utopian idea, has become reality, so there is no reason why a mineral resources agreement should not follow.