Introduction

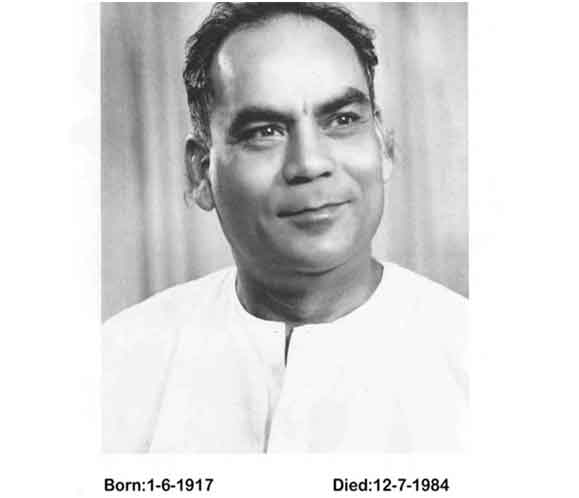

The first part gives a brief sketch of Com TN’s political life. The next section given below is an Extract from INDIA MORTGAGED, written by comrade Tarimela Nagi Reddy (1917-1976), legendary Communist Revolutionary, whose Birth Centenary is currently being observed in various programmes at different places across AP and Telangana, commencing from February 11, his birthday, at Anantapur, his home town in AP. TN and DV wished to be remembered by their views and practice, and not by statues and the like. Hence this tribute.

This Extract of 1970-71 period, though appears rather long, is worth reading in full, as it reflects the deep concern, and keen attention to detail, of the communist revolutionaries to the caste oppression, and atrocities against the most oppressed people, inseparably linked with the class question. It is to be noted that, with great anguish, passion as well as righteous anger, he was declaring all this in a Special Court, and through that to the Indian State. The Extract also recaptures a picture of the then prevailing socio-political situation in India, 45 years ago when most readers of this piece were not yet born, or were not in the know of things.

Today, 45 years later, we find basically the same situation, despite land reforms and capitalism’s advance in agrarian sector, and despite all the reformist measures and Constitutional- legal claims by ruling classes and their governments led by various political parties. Obviously, the development model, and the Constitutional-legal provisions adopted by them, made no basic difference. Not only Khairlanjis but also Unas were there then, and now too, as can be seen through the Extracts.

It may however be noted that the word Harijans, replaced by the word dalits, otherwise called as Scheduled Castes under law, was commonly used in political literature of those days. The extract is slightly abridged. Sub-headings and emphases are mostly added.

PART-1

Veteran communist legislator who said the legislatures in India are mere “talking shops”

The legendary communist leader TN, who began his life as a communist revolutionary in 1939-40, was a Member of Lok Sabha (1957-62), and three times (1952, 1962, 1967) Member Legislative Assembly, of Andhra Pradesh (AP), the first time in 1952 when he, from inside the jail, defeated N. Sanjiva Reddy, the first CM of Andhra Pradesh, and later India’s President. In over 35 years of his turbulent political life, he was imprisoned about 10 times, spent almost as many years in jail, and over five years underground, most of it in the ‘democratic republic’ post-1947. All the time it was under the same IPC, Indian Penal Code, of 1860 colonial vintage.

In the wake of Naxalbari and Srikakulam peasant armed struggles, he gave a historic speech in AP Legislative Assembly on March 11, 1969, in which the seasoned legislator called the legislatures as mere “talking shops” that did little to help the cause of the exploited and the oppressed, and resigned as MLA opting the extra-parliamentary, revolutionary path.

(See countercurrents.org July 28, 2016, Tarimela Nagi Reddy Remembered for more about him and his speech )

INDIA MORTGAGED, the immortal work by TN

INDIA MORTGAGED, the magnum opus by Com TN was originally presented as his Defence Statement in the Court of Additional Sessions Judge, Hyderabad, who conducted the trial of the famous Hyderabad Conspiracy Case 1970. There were conspiracy cases earlier against Indian communists, launched by the British, like that of Peshawar 1923, Kanpur 1924 and Meerut 1929-33, but this was the first ever after 1947, all under the same colonial law and similar sections including sections 120-B, 121 to 124 of IPC, with charges of conspiracy, sedition etc., now ever more frequent in India. Originally there were 68 accused in the Crime No 57 of 1969, but only 48 persons with TN as A-1 and DV as A-2 were tried and 18 of them were convicted in the verdict dated 1972 April 10. They were sentenced with Rigorous Imprisonment for four years and three months. It was a massive case that involved 325 witnesses and 824 Prosecution documents, and is cited by the police as a successful Text Book Case. This case was soon followed by the Parvatipuram Conspiracy Case with 140 accused persons and 502 witnesses being examined by the Court. Com TN formed, and worked as the President of, the Defence Committee for that case too. A big volume of about 600 pages with details of these (and a few other) historic Conspiracy Cases, in Telugu, was published recently in April 2016 by TN Memorial Committee with Satyanarayana Cherukuri, Advocate based in Guntur town of AP, as its Founder-Editor.

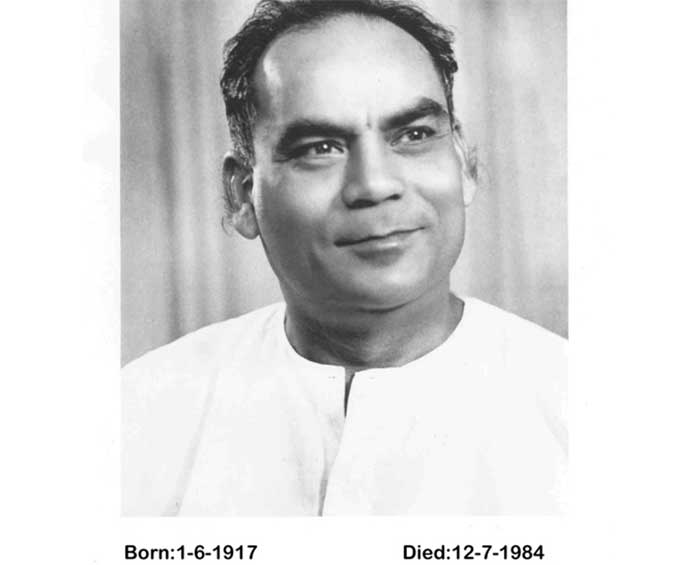

Com TN’s Defence Statement, made under Sec 313 of CrPC, was published in book form as INDIA MORTGAGED (of about 580 pages) , the first time in 1978 with a Foreword by his close comrade and co-accused, Com. Devulapalli Venkateswara Rao (1917-1984), veteran communist revolutionary known for his unique role in leading the Telangana People’s Armed Struggle (1946-51). The Telugu translation was first published in 1980. Later on several editions appeared, also in Hindi and Tamil. Com DV Rao wrote and made a separate statement, on behalf of nine accused leaders including TN, and read it out in the Court from Dec 14 to 18th of 1971. This magnum opus of DV Rao was later published in book form as People’s Democratic Revolution, An Explanation of the Programme (of around 370 pages). Together they served, as intended by the then imprisoned authors, as authentic text books and Hand Books for three generations of communist revolutionaries, with repeated reprints, unique in India’s revolutionary literature.

TN and DV : Inseparable comrades-in-arms

TN and DV, as they were popularly called, were, throughout their lives, unique and inseparable comrades-in-arms commencing from late forties, united as they were by the then revolutionary line of peasant armed struggle, Telangana being the first-ever application of Mao’s Thought in India, as signified by Andhra Thesis, 1948.

After an interregnum of parliamentary era of Indian communism that began with First General Election in 1952, they together formed APCCCR, revived and upheld the path of revolution marked by Naxalbari (1967) and Srikakulam (1968-1971) peasant armed struggles. They together led the fight against all forms of revisionism, against Soviet Social Imperialism and its Indian cohorts. They were together in opposing opportunism, both right and left varieties, upheld Marxism-Leninism-Mao’s Thought and its correct application to India and represented what is called revolutionary mass line, opposed to both parliamentary cretinism and left adventurism. They together founded, in 1975 April, UCCRI-ML, with Com DV Rao as its General Secretary. Com TN who together with DV Rao was all through in the Central Teams of India’s Communist Party since 1950, died early on July 28, 1976 of sudden sickness while being underground (during Internal Emergency period of 1975-77), and while being a CC Member of UCCRI-ML along with DV Rao who was its General Secretary from 1975 until the latter died on July 12, 1984.

It was coincidental that both were born in 1917 and both have their birth centenaries this year. Interestingly, both had interactions with Gandhiji as University students that drove both to begin their political lives as communists in late 1930s; both went underground since 1940s; both were Lok Sabha Members during 1957-62.

With common revolutionary convictions both quit CPI in 1964, and CPM in 1968; both were arrested under DIR, united as they were in opposing national chauvinism and wars, during India’s wars with China and Pakistan; and arrested again in December 1969, framed up, convicted and jailed together in Hyderabad Conspiracy Case. They came out on conditional bail pending their Appeal before High Court.

They together founded the UCCRI-ML in 1975 April that was soon after banned in 1975 June-July by Mrs. Indira Gandhi’s Emergency regime.

Both skipped bail and went underground at that time; and both died while being underground. They were united in their revolutionary political life, in dedicated work with the same line and organization, and in their death.

In a situation of perpetual and hair-splitting differences and splits amongst Indian communist leaders, no two communist leaders perhaps had such prolonged united life. This unity in their lives, work and views can be seen in several writings of both, and in the Foreword (1978 July) to the First Print Edition of India Mortgaged by DV Rao. The Foreword concludes with the following warm words that are apt to be quoted on the occasion of Birth Centenary of the legendary and immortal Indian communist revolutionary, com TN :

He loved the people immensely and the people reciprocated in the same degree. He is known for knowing the pulse of the people, and was acting accordingly. He was one of the architects of communist revolutionary line and he defended it against the campaign let loose by adversaries.

He was in Indian revolutionary political scene for more than 35 years. He sacrificed what all he had for Indian revolution. He is the product of the best in the Indian communist revolutionary movement. It is a proud privilege of communist revolutionaries to have him as their leader. (DV Rao 1978).

PART 2

Extract from : Chapter XIV on Agricultural Labour

We must also remember that wages are paid in various ways. Various forms of feudal relations exist, even in areas where commodity production and capitalist relations have developed. Sometimes the wages are paid in cash and in quite a number of places and quite a number of times – especially in the harvesting season – they are paid in kind; sometimes partly in cash and partly in kind.

“Capitalism penetrates into agriculture particularly slowly and in extremely varied forms” (Lenin), with the result that various forms of capitalist relations along with feudal exploitation co-mingle to make an excessive burden on the rural poor.

The feudal relations in our countryside are prevalent almost every-where. They have preserved almost all their medieval supremacy of the landlords over the peasantry in the villages.

In the following pages a few instances of feudal methods of exploitation will be given as examples of the prevailing and growing tensions in the villages. There is yet prevalent in the overwhelming parts of the country, a system known as ‘debt bondage’ or, ‘debt slavery’. A correspondent writing in Economic Times on June 1, 1970, on the state of the Harijans in Mysore describes the system as follows:

There is then the ‘Jeetha’ system – the pernicious practice of a system of bonded labour – something akin to slavery practised by the early American settlers. It is said to be practised in parts of Hassan district and also in South Kanara, north Kanara, Chikmagalur and Shimoga districts. The Elaya Perumal Committee describes the system thus : ‘according to the Jeetha system, the agricultural labourers are advanced petty sums of money in time of their need. They are bound in such a way that they are not able to repay the debt out of their meagre wages because under the terms of the bond they got food, cloth, and small salary only. The result is that they are not only unable to repay the loan but also have to add to it. Consequently their debt increases. Even their children are obliged to take upon themselves, the repayment and become involved in it.

Thus the lords of the land have even retained the jurisdiction over their ‘labourers’. They have preserved almost all their medieval practices, including various forms of free labour. It is true feudalism is flourishing more in some localities than in others, but the fact is that nowhere has it been entirely destroyed….. For example, the system of attached labourers is prevalent all over the country

Thus the attached labourers are characterised by debt bondage, caste restraints, tie-in allotments of land, indicating prevalance of precapitalist features of employment of labour. Attached labourers are tied down by loans, repayment of which were practically impossible.

Moreover, in many cases the employers give the attached labourers house-sites and land sometimes on a share-cropping basis. In South India large numbers of farm servants known as padiyala, pannaiyala, pulayas, paleru, jeeta, etc., work year after year, if not generation after generation for the same land-owner families.

Such a medieval system of bonded slaves, according to the Second Agricultural Labour Enquiry Report, is on the increase. The percentage of attached labourers among all agricultural labourers increased from 9.7 percent in 1950-51 to 26.63 percent in 1956-57.

There is no doubt that considerable section of the agricultural labourers in India are victims of pre-capitalist exploitation; semi-feudal feature of wage payment in kind is prevalent in vast areas of our countryside; it was revealed by the Second Agriculture Labour Enquiry Report that the employment situation as well as the terms and conditions of employment have markedly worsened over time…., they are employed only 200 days a year.

The agricultural labourers are not part and parcel of the village. They are forced to live outside the main village, in separate ghettos, under horrible conditions, without any common facilities such as wells for drinking water, roads, street lanes, etc. They are mostly illiterate.

When such are the conditions, and they are becoming worse with feudal appropriation and exploitation taking open forms of violence against agricultural labour (many more instances will be given later in this chapter), it is disgusting to note that the Soviet revisionists are showering praise on the Congress government for having implemented ‘partial bourgeois agrarian reform’. …

Even the Economic Times, June 1,1970, calls this system no better than ‘age-old serfdom’. As Ranjit D as Gupta has written, “The inter-twining of the pre-capitalist methods of exploitation and the capitalist method has subjected the underprivileged groups of rural India to absolute and relative impoverishment”.

In addition to this, they are socially oppressed in our caste-ridden society. The overwhelming majority of agricultural labourers belong to untouchable or backward castes. Social ostracism of those castes is worse than the whites attitude to Negroes in America. They are obstructed from using the wells, tanks, temples, and other public places.

The reason for this is that, during the British period, there was no fundamental change in the character of the Indian economy which remained essentially semi-feudal and semi colonial in character.

“Fundamentally caste has remained the same.”

Even after the transfer of power from the British to the Indian comprador class, no fundamental changes in the economic, social and administrative spheres had been achieved. Even to this day, the character of the Indian economy has remained essentially semi-feudal and semi-colonial.

Forms in some respects have changed, but fundamentally caste has remained the same. The system of Panchayat Raj, the growth of green revolution, the growth of commodity production in the countryside, have only helped the ruling big landlord and the big business class to increase their domination through the revivalist and obscurantist social ideology based on castes.

The primary condition for lifting agricultural workers from this horrible state in which they have been forced to exist is the elimination and extermination of landlordism. Fundamental changes in the agrarian structure and social relations in the rural areas can be achieved only through an agrarian revolution.

Untouchability

The problem of untouchability is inter-related with the problem of rural land relations. The extent and magnitude of the problem of untouchability is the reflection mainly of the economic lot of the scheduled castes, and a reflection of an economic society with feudal social and economic relations which are still strong. The economic relations in the countryside are such that they are entirely dependent on the high caste landlords.

Due to the “increasing power of, what is called in India the ‘rural elite’, “the caste system is probably stronger “ today than it was at the time when India became independent. Caste is so deeply entrenched in India’s traditions that it cannot be eradicated except by drastic surgery.”

(Asian Drama, Page 279)

The problem of untouchability can be solved only by a hundred per cent democratic revolution capable of smashing to smithereens the feudal landlord hold in the rural areas, under the impact of mass uprisings, by total elimination of landlordism.

Tension has been growing between landlords and agricultural labourers in various pockets in our country. Writing in the Economic Times (July 9. 1970) about the tensions in Thanjavur, in relation to the intensive agricultural district programme, the paper’s special correspondent noted that ‘the disturbing aspect is the running feud between the landlord class and the agricultural labour in half a dozen taluks constituting the eastern wing of the district “culminating in a “ghastly incident in which 42 persons, mostly women and children, were burnt alive”. Struggle for fair wages unleashes the fury in un-imaginable magnitude, among the landlords on the downtrodden agricultural labour.(The reference is to Kilavenmani incident, of Tamilnadu, mentioned elsewhere).

Scheduled Castes and Tribes in India

Nearly 90 percent of the scheduled caste population and more than 97 percent of the tribal population in the country is residing in the rural areas. They form 15.97 per cent and 8.16 percent., respectively, of the rural population.

Literacy among the scheduled caste and scheduled tribe population is very poor in India compared to the general literacy rate. The 1961 census shows that only 10 per cent of them are literates as against 24 per cent for the general Indian population. Among the literates, the majority constitute those who are “literate without education level”.

The over-whelming majority of the scheduled castes and scheduled tribe people are in the rural areas, and most of them are engaged in agricultural labour. As such, the emancipation of these people cannot be achieved separately and in isolation from the general problem of rural poverty.

This cannot be achieved without revolutionary redistribution of land and forcible and violent overthrow of landlordism. In short, the problem of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes can be solved only through a revolutionary change in the socio-economic structure of the country as a whole.

The State of Harijans

Economic Times produced a series of articles on the state of the Harijans in 1970. A few extracts reveal the fact that they – the lowest stratum in society both economically and socially – are being treated worse than serfs of medieval society

IN PUNJAB : They have to live in Bastis away from the socially better-placed community. They are not permitted to draw water from wells of the people of ‘high castes’. Although there are hand-pumps in the village, the Harijans are not allowed to touch them in Dehra village in Dera Basia sub-division.

Last year, a socio-economic survey was carried out, by the Planning Forum of the local Mahendra college, at village Daun Kalan, a model village in the vicinity of Patiala. It was found that though the village was economically well advanced, having a high school, a post office, an industrial training centre, a primary health centre, and other amenities, yet it was socially backward, so much so that the Harijans were not permitted to draw water from the wells of the localities.

In the village high school, there was not a single student belonging to the scheduled castes though there was no bar on admission. The overall rise in prices has forced the landless labour to demand a better wage and, wherever they did so, they face resistance from the land-owning class. Trouble arose about three months ago when the foundation stone of a village school was laid by a Minister and the Gram Panchayat donated land for a playground of the school. Incidentally, the playground included a part of such land which was within ‘lal-lakir’ (residential units of the village) and was not ‘shamlat’ land within the meaning of Punjab village Common Lands Act. While donating the land the panchayat ignored the hard fact that the Harijan families would be put to great difficulty in case no passage was provided in front of their homes. A barbed wire was raised around their houses, by February 20, 1970. On March 22, a study team of the Punjab Pradesh Congress (R) led by its president Mr. Zail Singh visited the village and found entry to two houses completely blocked. “Such incidents have multiplied during recent days throughout the state, because the police mostly acted as a silent spectator.”

The problem of untouchability is basically the problem of social and economic inequality. Harjians are considered a necessary cog in the age-old agricultural production system meant to provide cheap labour to the land-owning classes.

The old social order is resisting the new trends as a result of which a huge majority of Harjians are condemned.

Even after two decades of Independence, the social, economic conditions of scheduled castes in Punjab have not registered any marked improvement according to an official survey recently conducted in the state.

A number or instances have been given in the report where other classes used their economic power as one of the weapons against those depressed classes in the villages particularly in situations when the scheduled castes make attempts to exercise their rights. It has taken the shape of their eviction from land, discontinuance of their employment, and stoppage of their remuneration as village servants.

The report, pointed out that the per capita income of the scheduled castes population in the rural area of the state was Rs. 194 as against Rs. 483 for the general population for the year 1963-64 (Economc Times, June 29, 1970).

IN MADHYA PRADESH :

(1) A Harijan labourer was prevented from working at the construction site of a temple.

- In one case in a temple constructed by Harijans themselves, they were prevented from offering worship.

- In Mandazur, one Chamar bridegroom was made to get down from the horse on which he was riding because it was the privilege of the caste Hindus.

- Untouchability is also practiced in selected institutions. Reports are often received that, in the Panchayat meetings, elected Harijan members are made to squat on the floor, outside the main door of the meeting hall, while caste Hindu members occupy the chairs.

“Various reasons are being listed for the ineffective enforcement of the untouchability law”. One of the main reasons is “the indifference of the police towards such complaints. Such offences are generally committed by people of high caste, who also happen to be influential persons of the area. In addition to this, feudal landlords furnished a large percentage of high government officials.”

“Land to the landless Harjans is a perpetual demand in the state. Allegations of discrimination, partiality, favouratism, and watering down of the provision of the scheme of land reforms are often levelled by the representatives of the backward communities. In fact, the Situation has become so explosive that unless the government evolves a fool-proof procedure, it might explode any day.” (Economic Times, May 24, 1970).

IN MYSORE : Recently, a party of press men who were taken to a village in Kolar district by some Harijan leaders, were shocked to find that Harijans are still prevented from drawing water from common wells and are literally ostracised by the higher castes.

Democracy itself plays into the hands of petty plutocracy.

As a result of age-old serfdom, the Harijans have almost lost their faculty of reacting to injustice. Thus, the inequities have been solidified by the rigid social stratification, of which the caste is the most. significant manifestation. Political decentralisation, or panchayat raj, has strengthened their position further by offering them more opportunities for political office and patronage.

M.M. Srinivas, has described the inherent conflict of interests as follows :

“The rural elite has emerged as a class keenly conscious of the political and economic opportunities lying before it. It does not have any inhibitions about exploiting these opportunities to its own advantage. A basic contradiction needs to be mentioned here. In implementing programmes for the benefit of rural areas, government officials tend to be guided by the rural leaders who are part of the rural elite. But it is forgotten that there is a fundamental conflict between the interests of the rural elite and the rural poor. The rural elite are, as a group aggressive, acquisitive, and not burdened by feelings of guilt towards the people they exploit. Hierarchy and exploitation are so deep-seated in rural India that they are accepted without questioning. Neither the urban politician nor the administrator can do without the rural elite and the latter know it.” (Yojana, October 1, 1961).

Thus democracy itself plays into the hands of petty plutocracy.

In such circumstances, it is no wonder that contradictions are growing in the rural areas going to the extent of violent clashes. Wherever and whenever the Harijans and other backward caste rural poor assert their social rights, or fight for better wages the socially superior high caste landlords make use of this division of caste to throttle this legitimate assertion of their rights by all violent means. There are innumerable instances of these people beaten and even killed appearing in the Press. There is no hideous crime that is not perpetrated against untouchables and back-ward classes.

Violence and feudal gangsterism Stalks the Rural Scene

With the growth of the power of the rural elite, there is growing violence in the countryside. In recent years, unheard of atrocities committed against the poor in the rural area, especially on the low-caste section, have been growing in number. Social, economic and political contradictions are developing into direct confrontations, with landlords taking law into their own hands with a ferocity unheard of at any time in the past. The Ku Klux Klan is being outdone. Nazi atrocities in Germany on Jews are being re-enacted in India’s country side by the all-powerful feudal landlords.

It is my opinion that armed landlords have created and are creating a situation, wherein there seems to be no way out except armed confrontation in defence of their legitimate rights by the rural poor.

According to the Union Home Ministry’s information 93 Harijans were done to death in different parts of the country in 1969. The office of the scheduled caste commissioner has reported 355 cases of harassment of Harijans, some of them involving rape and murder.

Rarely have the culprits been brought to book. Rarely is the violator of the law punished. This criminal indifference of the authorities is not accidental. These limbs of the State are closely linked with the upper strata of the society, which is the main rural base of the Government. Harijans, as agricultural workers and landless peasants, are the worst exploited not only economically but socially.

I propose to bring to the notice of the court various incidents that have been reported in the ‘respectable’ Press, from which it is explicit that it is the landlords, under the supervision, blessing, and connivance of the administrators, who have been responsible for the violence in the country.

I would like to ask: Is it not the legitimate duty of the people to counter violence with violence?

Let us first look at the facts – at the magnitude of the issue. confronting us before we come to any conclusion. For, that would give us an idea of the type of feudal gangsterism stalking this land, an idea of the various issues involved and a glimpse of various methods adopted by the landlords.

Patriot (daily newspaper) on December 11, 1968, reported that an attack of armed gang on Harijan cultivators took place in Dharmkot-Zira section of Ferozepur district in Punjab. In this incident, huts were set on fire, crops were destroyed, and the cultivators were tied up and beaten.

The paper remarks that, it would not have been so disquieting but for the fact that it is the latest of a series of such outrages which have not been confined to one or two states.

There have been a series of incidents all over the country in which Harijans were murdered, their women molested, and their dwellings smashed up. There is a sinister pattern in the way Harijans have in recent months been terrorised and bullied in AP, MP, UP, Rajasthan and elsewhere. “Sympathetic noises from the top will not end this untenable situation. Drastic action to purge the administration of caste-mongers is the only alternative to the Harijans organising themselves for self defence.”

Now let us take the incidents mainly in the years 1970-71.

National Herald of May 28, 1970, reports that 54 Harijans belonging to 13 families were rendered homeless after their homes were set on fire allegedly by a large group of caste Hindus on the midnight of May 20, in Masania village in Dhenkanal district of Orissa.

Statesman, August 7, 1970, reported that in Tamdei village, of Sambalpur, four brothers belonging to a Gonda (Harijan) family were burnt to death on July 18, over the question of fishing rights.

Indian Express, in an editorial on August 6, 1970, writes as follows: “In recent months, there have been several other instances of atrocities committed against Harijans primarily because of their being Harijans. Following a petty quarrel between a caste Hindu and some Harijans, all huts in the Harijans quarter of an Orissa village were set on fire in May. A shocked Rajya Sabha was recently told by an M.P. from Maharashtra how a young Harijan woman was burnt to death in her state nearly two months ago. Reports about Harijans being tortured for drawing water from certain wells or for entering temples continue to come from many parts of the country.

“In most states the problem of untouchability is getting mixed up with the question of land reforms. This has created new tensions in rural society dominated by the upper castes.

The Bhubaneswar report about killing of some Harijans in a clash over possession of land in a village near Puri is a significant pointer. The question of wages of farm labourers is another source of conflict. The way the Harijans of a village near Patiala were harassed by the local panchayat a few months ago over the wage issue was truely incredible. Their houses were fenced off by barbed wire with the help of public funds because they refused to work for a daily wage of Rs. 2.50 which was less than half the nominal rate in the case of non- Harijans in the area.

“Even more shocking than these incidents is the apathy of the authorities. The state governments appear to have failed signally in securing for the Harijans their legitimate rights”.

Patriot reports on December 20, 1970, an incident in which the Harijans were being evicted from the lands which they have been cultivating for quite a number of years.

“According to Bahadur Singh, sarpanch of the village Ganna Oind in Phillavar tehsil in Jullundur district, Punjab, 24 Harijan families were allotted a plot of land by the government. After they had developed this land and installed a tubewell, one senior police officer of Ludhiana district, in collaboration with the revenue officer of the area, got the allotment cancelled. To get possession of the land he organised a police raid on the Harijans of this village in which one woman was seriously wounded. A report was lodged and no action has been taken.

“The story of Harijans of Talwand Canal is that one senior officer of co-operative societies is seeking to get Harijans evicted from the land in this village through bogus entries in the revenue records in favour of his relatives.”

Times of India, March 24, 1971, reports that Choti Khatu, a fairly big village with a population of 4,000 wears a deserted look.

About 30 to 40 Baori (scheduled caste) families lived in and on the out- skirts of the village. The 12 houses owned by the Baoris, some of them pucca, were demolished by miscreants. Four huts in the fields were burnt. The panic stricken villagers who fled have left behind all their possessions – rags, broken chappals, lanterns, charpoys, and flour-grinding stones. Even earthern pots used for storing food grains were smashed and the grains were carried away.

30-year-old Pipli, mother of five children, said. “I and three others were dragged out of our houses on the evening of March 9 and beaten up mercilessly. Afterwards, some people brought Jarhwali, who was carrying her six year old child in her arms. She too was belaboured so, the child died in her arms”.

Another woman, also called Pipli, was beaten up and kicked despite being in-an advanced stage of pregnancy. She gave premature birth the same day.

Times of India, March 26, 1971, reports about a social boycott of Harijans organised by the president of a village panchayat in Mysore State. How total the boycott was can be seen from the fact that the village grocer did not sell provisions to Harijans; the blacksmith and the potter refused to have any dealings with them; and even the priest barred their entry into the local temple.

“One panchayat in Punjab is said to have gone so far as to order Harijan houses to be “walled off from the rest of the village. Panchayats are supposed to foster democracy at the grass roots, but in practice many of them function like tiny oligarchies.”

Patriot, June 21. 1971, reports on Khurja village Harijans fleeing landlord terror. “About 15 Harijan families of a village in Bulandshahr district of U. P. have fled their homes following a reign of terror let loose by a big landlord there.”

“It was the reluctance to do a certain job by a Harijan lad of 18 years that made the Harijan basti the victim of landlords’ anger, who threatened to shoot them, and to escape it the 15 families fled their homes” and “are now in the capital, to meet and seek redressal from Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and are camping under a big tree outside Teen Murthi”.

“The landlord felt offended at the protestation of 18-year old Shohanlal, who, after working three or four hours of household chores at the landlord’s house, was refused a break for tea, even though the boy went home only after he completed the work.

“Even so, the landlord felt aggrieved. He, along with his nephews, went to the boy’s home and beat him. When his mother protested she too was kicked on the belly. The boy’s young wife was treated in the same manner. When the boy’s father who was then absent tried to raise the issue with the village panchayat, it refused to take cognisance of the incident. A complaint lodged with the police the next day had no effects for the next two days, the landlord again visited the Harijan basti and threatened to shoot them all if they did not report for work the next day.

“Struck by terror, the Harijans collected whatever they could from their houses and fled in the night and reached Delhi by train from Khurja.”

Patriot, June 22, 1971, makes an editorial comment on the rural anger. The rural landlords practising their privileged morality have increasingly set regressive social standards across the country. Thakurs, Gounders or Reddys, they all use the Harijans ghettos outside the villages for the daily conscription of cheap labour, or dead of the night forays for women and will not concede them any civilised rights as part of society.

“There have been many Kanchikacharlas in Andhra Pradesh after the first tragedy. Huts full of ‘rebellious Harijan labourers burnt alive in Kilavenmani, and many groups of terrorised men, women, and children, have fled UP border villages to Delhi and there does not seem to be anything much any one can or will do because most seem to accept that this is all part of the Indian condition – only some regretfully. The UP land-owner who threatened to shoot a family and drove them out of their village was only following standard practice. The outraged Gounders of the Coimbatore village, hit where it hurts most by the elopement of one of their girls with a Harijan boy, may be preparing for a small war of their own. For both, police help is assured since police force identified itself with the ruling or powerful interests not the weaker sections….Though ‘dadas’ are emerging among the Harijans who will sell the community’s interests, it looks as though a rural confrontation of some magnitude is inevitable unless the police are de-linked from the land-owners and the State apparatus moves to protect the weaker sections.”

Blitz (weekly), August 21,1971, reports how in Kanail village, in Gorakhpur, a Harijan boy, Samuru, was tied to ‘Khamia’ and beaten by an ex-zamindar whose fields he refused to plough when the zamindar insisted the boy should work free for him as his family and fore-fathers allegedly owed him Rs.1,32,000.

“Denying the existence of a slave trade amongst the tribals of Wynad, Kerala’s Minister for Harijan Welfare admitted that there was a system under which the tribal people were tied down by contract for a particular period to individual landlords.”

“A marriage party of Harijans was allegedly beaten up by Rajputs in Bikaner village temple, while in Ganganagar district a Harijan was beheaded and thrown in a well.”

Statesman, August 22, 1971, reports that Harijans were stunned by the announcement of social boycott, made in Duneka village, two miles from here (Moga) last night.

“The Harijans were told by the beat of drum that they would not be allowed to step on farms owned by the people in the village.”

“The social boycott reportedly follows the Harijans’ demand for wages in excess of the rates fixed by villagers of the area.”

Patriot, September 2, 1971, reports the ejectment of Harijan cultivators of common land in the village Kheri Ganeran, 12 miles from Patiala, which has whipped up tension in the village.

“The total area of the village common land is 380 bighas of which 107 bighas had been leased out to Harijans for cultivation for the last several years by the village panchayat. Now, the entire common land area in the village is in the possession of the high caste cultivators.”

Patriot September 2, 1971: Mr. Sundersingh, General Secretary, Congress Legislature Party, today alleged that the Harijans in Punjab were being harassed and ousted from their land. He also alleged that the Harijans were being killed on the false pleas that they had become Naxalitcs.

Times of India, September 8, 1971, in Current Topics says : “How can Harijans be blamed for feeling that there is built-in hostility against them in the administration?

“A new road had been constructed in a village in south Arcot district of Tamil Nadu for their’ exclusive use. It appears that the caste-Hindus of the village objected to the pollution of the regular road by the Harijans.”

The conscience of the ruling class is shocked when they hear that South African whites put up boards for railway compartments and hotels. “Dogs and Blacks Not Allowed”. Yet this ‘soft-hearted’ ruling class is no worse in their treatment of village poor.

The Hindu, September 10, 1971, report, of two cases of assaulting scheduled caste persons for entering a temple, figures today in the Maharashtra Assembly during question hour.

One incident occurred in Deogaon village, Ahmednagar district, on April 20. In another incident, a 60-year-old person of the same caste was beaten up by a sarpanch of Govhan village in Sangli district on May 22 last as he entered a Hanuman temple.

“When the opposition members demanded disclosure of the names of the accused, the Minister expressed his inability to furnish them. He, however, promised to produce the names in a day or two according to the direction of the Speaker”.

Patriot, of September 11, 1971, reports of terror-stricken Harijans fleeing a Rajasthan hamlet. Palwala Jataun, a small village in Bassi tehsil of Jaipur district in Rajasthan is today without a single Harijan. All the 40 Harijan families of the village have fled their homes in the wake of terror let loose against them.

“The incident was a sequel to the village cobbler’s refusal to mend, free of charge, the footwear of the caste Hindus. Such refusal was contrary to the traditions still followed in many Rajasthan villages that the cobblers mend old footwear of these persons free of charge.”

“A mob of caste – Hindus started wanton attacks on Harijans, indulged in arson and looting. About 10 Harijan houses were turned to ashes.”

“These people (Harijans who had come to the capital) complain that in many villages the Jats and the Thakurs were terrorising the Harijans. They had virtually made it impossible for any cobbler to live in the village. They also sometimes forcibly occupied the lands of Harijans or deliberately destroyed the standing crops from their fields”.

Times of India, in an editorial on September 15,1971, says:

“There is hardly a week which does not bring to light a fresh instance of the practice of grossest kind of discrimination on grounds of caste.”

After giving the instance of denying the use of public road to Harijans in a village in South Arcot, the editorial says that, this is a case “not just of discrimination but a reign of terror instituted with impunity under the very nose of government that revels in anti-Brahmin militancy”.

“The Harijan of the village is so defenceless today that, even where he knows he has been wronged and authority is ready to help him secure justice, he does not dare complain for fear of reprisals from the privileged part of the community, which, as the South Arcot example shows, can make life impossible for him. Land reforms have helped flatten the agrarian pyramid but not touched the base.”

“The result has been a sharpening of tensions between land owning caste Hindus and landless Harijans. Social thrust of the Green Revolution is in the same direction.”

When Chamars decided ……

not to remove and skin the dead animals any longer…

Patriot, September 18, 1971, talks of casteism running amock in Behara. “The Harijans of Behara, victims of a barbarous assault, are bitterly complaining that the days of serfdom are not yet over”.

“The chamars of the village traditionally remove dead animals. It has been obligatory all along as a part of the job of the landless labour whose current wages are Rs. 3 a month and half kg of coarse grain a day.”

“At a meeting on Sunday, the chamars decided not to remove dead animals any longer. The decision was unanimous”.

On Tuesday, a group of caste Hindus, some Thakurs and other influential persons, ransacked the Harijan basti; their shed roofs were set ablaze. Pots and pans were broken. Women and children were beaten up indiscriminately. The rampaging crowd did not leave until they killed one person. It is believed that the object of the attack was to terrorise them into continuing to perform the traditional services.

Times of India, September 21, 1971, reports how a Rajasthan Harijan tribe fights exploitation. The Reghars, a community of scheduled caste people, have fled Palawala, Ramura, Paterha and Bakri villages in Jaipur district following a series of clashes with the land-owning caste Hindus the past two months.

It is socio-economic tensions that have led to these clashes. “Part of the trouble is traceable to politicians who have been resisting socio-economic changes in the countryside.”

FEUDAL RELATIONS:

The Reghars had for decades been skinning cattle, tanning hides, manufacturing and repairing charas (leather buckets) for drawing water from the wells, and repairing old shoes.

“While they used to be paid cash for providing new charas, they had to accept food grains at harvest time for the rest of their services.”

“With the growing socio-political consciousness, these arrangements are no longer acceptable to the community of Reghars. With the growing money economy, it is but natural that the Reghars are insisting on wages in cash for their services .

“A large number of meetings have been held over the past few months to press the demand for a better deal for the Reghars. At one of these meetings the Reghars decided not to skin cattle or repair old charas and shoes unless paid in cash”.

To counter this agitation of the Reghars, “the farmers set up Kisan Sangharsh Samiti to hit back at the Reghars”. The Samiti decided to impose social boycott on the Reghars. They took back the fields leased out to Reghars on a share-cropping basis. The Reghars were also banned from grazing their cattle in common grazing lands. They were prevented from going to their fields or houses through traditional short-cuts. They were not allowed to draw water from private wells. The supply of provision from village shops was stopped.

At Palewala, 300 to 400 Jats and Brahmins with their servants surrounded the houses of the Reghars, beat up the men and women, as well as children, and looted their property.

At Bakri, the Reghars were prevented from taking water from a private well.

In some instances, the Reghars were prevented from taking possession of land allotted to them by the government.

“Despite these reprisals, the Reghars seem determined not to repair old charas or shoes. They are equally bent on not accepting food grains in lieu of wages.”

LAND FOR THE POOR:

As this demand of the landless poor, the bulk of whom belong to the scheduled castes, continues to grow in intensity, the Congress government more and more has intensified its propaganda of land reforms on one hand and has been stealthily helping a concerted move to oust them even from the small bits of land that agricultural labour possessed. The following bit of information in Patriot of September 14, 1971, is of interest.

“In Porbandar taluk of Gujarat, 20 Harijan families have been driven out of a village where they had lived for generations, their crime being that they owned small pieces of agricultural land.”

“In the Patiala district of Punjab, influential persons are in illegal possession of Nazul land transferred to Harijans, in connivance with the officials.”

“In U.P. districts of Bulandshahr, Agra, Hamirpur, Nainital, Baharaich, etc., what was revealed by the preliminary survey reports of distribution of fallow land to the landless is disconcerting. In the majority of the cases, land has been found to be allotted by the village land management committees to those who already own big slices of land or have other sources of income, as per the provision of the existing land law which treats even a person, whose parents own enough land, as landless.”

“Though the government claims that most of the waste and surplus land has been distributed among the scheduled castes and from time to time produces impressive statistics to substantiate it, in actual fact hardly any land has come into their physical possession.”

“Under the circumstances, if the scheduled castes plan direct action, they are more than justified.

It is also widely alleged that the authorities are resorting to a more suitable device to deprive the Harijans and other poorer people of the land they had been in possession of for generations, by acquiring them for public purposes. Cases of land acquired for Meerut University along the Ghat Road and for other similar public purposes. Aligarh are being cited in this connection.”

Casteism strenghthened by state agencies

Desperate Fury Inevitable

These incidents cannot be dismissed as those unrelated to the class war now raging in our country in various forms. Some of the problems in rural India of today arise from the fact that economic relations which have become outdated still persist in our villages due to the unbalanced economic development of India.

The traditional system of caste interdependence, under which poor peasants and labouring class mainly belonging to lower castes attached themselves to the landlord families, still persists.

Those people belonging to the upper castes, who had previously lived on tributes and taxes from the producing and serving castes as feudal rent- receivers, maintained their social and economic domination under British rule in the newly evolving class structure.

Their rule in society was further established and strengthened after the comprador bourgeoisie and the landlords took over power from British imperialism.

The co-operatives, bank loans, better seeds, fertilisers, and other economic benefits which the rich classes, belonging to the upper castes received, along with the establishment of panchayats, samithis, and zilla parishads, which gave them a direct link with the administration from bottom to top, strengthened them not only economically but also politically.

On the other hand, the overwhelming majority of the low-caste people, the serving castes, remained at the bottom of society as landless and semi-landless labourers.

Thus, though certain changes did take place in society, these were mainly within the caste system of the feudal structure, instead of breaking away from the institution. Forms may have changed but fundamentally caste remains the same.

The reason for this is that, during all these years, there was no fundamental change in the character of the Indian economy which remains essentially semi-feudal and semi-colonial in character.

Even the distinction of wealth in an economy of commodity production led to further intensification of the caste institutions.

As Ranjit Das Gupta in his book Problems of Economic Transition states :

“Planning efforts and various agricultural development programmes, including the much- lauded new agricultural development policies, helped to increase disparties between region to region, and between different strata within a region, benefiting most the large land-owners and the upper strata of the peasantry; land has given a new life to this hierarchical caste structure and even strengthened it in certain respects in the rural areas.”

“The dimension of the problems flowing from the pervasive persistence of the in-equalitarian caste structure is revealed by reports of burning alive of women and ; children of Harijan agricultural labourers in Tanjavur district of Tamil Nadu and the spate of violence against scheduled castes going on widely in separate parts of the country “.

This “solid foundation of oriental despotism”, as Marx brilliantly exposed, continues to exist with all its ferocity, strengthening “stagnatory, undignified and vegetative life”, “contaminated by distinctions of caste, and slavery”.

But the rural masses are awakening. Slowly, but steadily. A sense of revolt against economic and social despotism is growing. “While the promises given to rural masses are belied”, writes Yogesh Vajpeyi, in National Herald, in his series of articles on ‘Indian Village’, “awareness is dawning among the sufferers that this state of affairs cannot be tolerated anymore.”

And the villagers are realising that the tables cannot be turned upside down by playing the game according to rules of those at the top.

“This is a dangerous stage, for after the realisation that the conventional means are ineffective comes desperation, and direct action germinating out of desperate fury is rather uncontrollable.” (National Herald, May 10, 1970)

It is no wonder that the masses have come to believe that

“It is utterly useless to professedly use merely legal means of resistance against an enemy which scorns such scruples.” (Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, German Revolution and Counter-Revolution, Page 110)

Therefore, if the class character of the revolt of the exploited sometimes expresses itself in certain castes, and if the suppression of the downtrodden exploited classes takes the character of a brutal war against certain castes, it in no way obscures the basic character of class struggle. During British rule, the rural masses were so much steeped in the motion of caste and communal segregation that even their political and economic revolts sometimes took a peculiarly obscurantist character, as was the case with the Moplah Revolt in Malabar.

Here is how Engels, the greater partner of the founder of Scientific Socialism, Karl Marx, analyses the so-called religious wars of Medieval Europe:

“Even the so-called religious wars of the sixteenth century involved positive material class interests: those wars were class wars, too, just as the later internal collisions in England and France. Although the class struggles of the day were clothed in religious shibboleths and though the interests, requirements, and demands of the various classes were concealed behind a religious screen, this changed nothing in the matter and is easily explained by the conditions of the time…. the revolutionary opposition to feudalism was alive all down the middle ages. It took the shape of mysticism, open heresy, or armed insurrection, all depending on the conditions of the time. “

( F. Engels : “The Peasant War in Germany”)

(Compiled by MK Adithya. He is a media person. See also his write-up on DV Rao published by countercurrents on July 12, 2016.)