In the era when most of the government regimes all over the world are being installed by the multinational companies and transnational corporations behind the garb of parliamentary electoral set up or in the name of democracy (21st century’s – White man’s burden) to facilitate naked plunder of natural and human resources; it then becomes the responsibility of every person to revolt against the dictatorship of the capitalist class all over the world and work towards the establishment of an egalitarian society.

In India, there has been a constant struggle by the exploited masses (Dalits, Adivasis, Women, Minorities) against the dominant ruling classes-castes, the agents of imperialism and their infrastructure of political governance and social institutions since last century. This struggle has intensified since the transfer of power from British colonizers to their agents of imperialist capital. The first phase of revolutionary communist movement in India started with the Telangana movement. Before Naxalbari, Telangana movement had already set precedence to a well organised Communist Revolution.

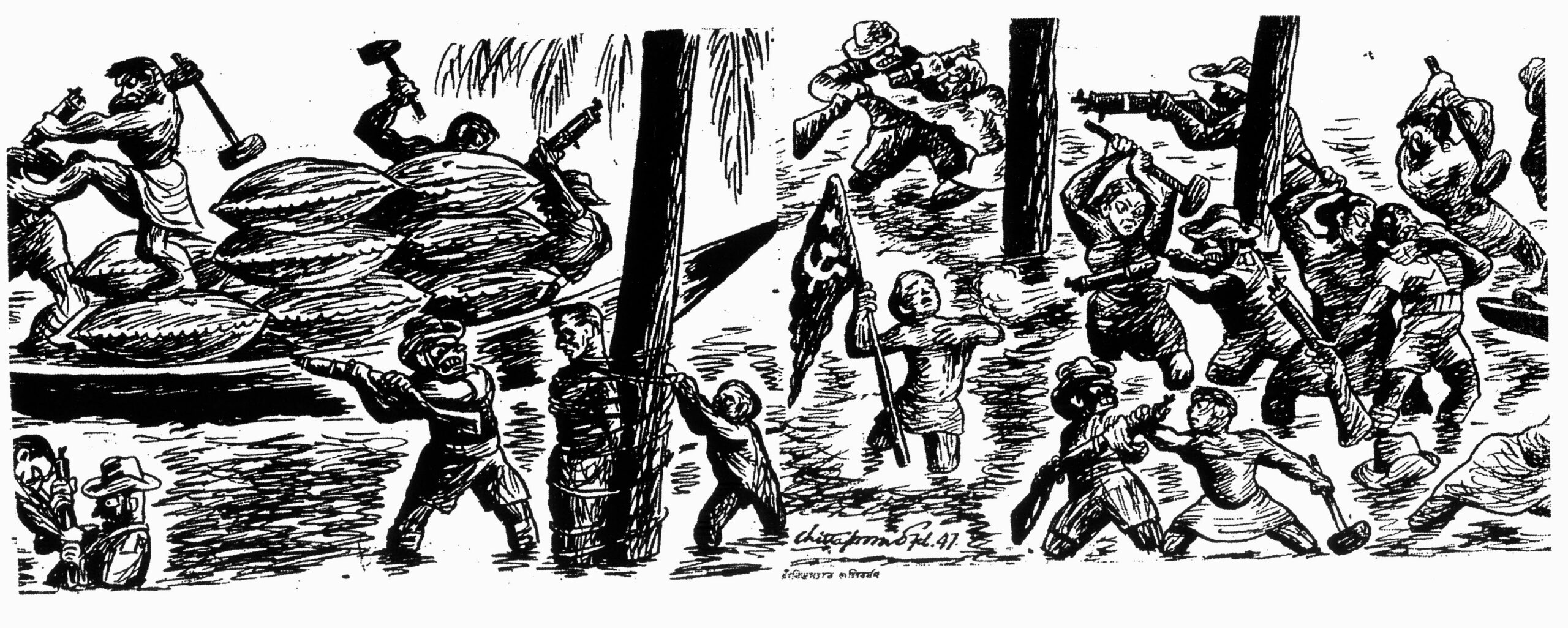

“By 1947, a guerrilla army of about 5000 was operating in Telangana. During the course of the struggle which continued till 1951, the people could organize and build a powerful militia comprising 10,000 village squad members and about 2,000 regular guerrilla squads. The peasantry in about 3000 villages, covering roughly a population of three million in an area of about 16,000 square miles, mostly in the three districts of Nalgonda, Warangal and Khammam, succeeded in setting up ‘gram-raj’ or village soviets. The landlords were driven away from the villages, their lands seized, and one million acres of land were redistributed among the peasantry. In the brutal suppression by the newly independent state of India as many as 4000 communists and peasants were killed, and more than 10,000 communists and sympathizers were put behind bars.” (Sumanta Banerjee, India’s Simmering Revolution: The Naxalite Uprising)

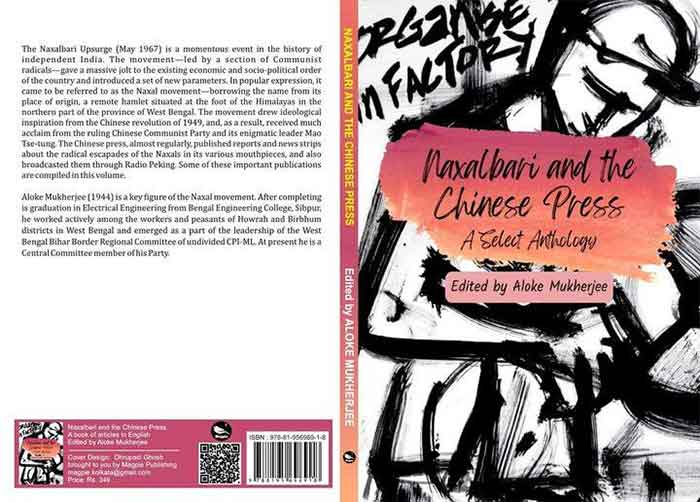

But the Naxalbari movement differed in two ways from the Telangana movement. Firstly, in its fight against the comprador bourgeoisies, and against increasing domination of American imperialism in the country. Secondly, in its struggle against the revisionist and opportunist parliamentary communist parties. Charu Mazumdar who led the struggle states in his writing that “the People’s Democratic Revolution in this country can be led to a victorious end only in opposition to all the imperialist powers of the world.” And this is possible when we break the economic structural base on which Imperialism bases itself in the country. He writes: “Because forty crores of people out of the total population of fifty crores live in the rural areas…feudal exploitation continues to be the main form of exploitation to which they are subjected, the contradiction between the peasants and the landlords in the countryside remains even today the main contradiction.” To uproot this, the only way is “the establishment of liberated zones by the peasants’ armed forces under working class leadership.” (Suniti Kumar Ghosh, The Historic Turning Point: A Liberation Anthology)

Such detailed and experienced understanding of the contradictions in the country, and chalking out of the way forward was the beginning of the revolution in India. The shivers it sent down the spine of the dominant ruling classes in the country made them use the coercive machinery of the state to crush down the movement. But the movement was far from being getting suppressed. The correct recognition of the enemy classes and the use of armed resistance, rejecting the path of parliamentary politics appealed the oppressed masses and many sections of middle class to join the movement. For dalits this revolutionary communism was also the way forward. The movement soon spread all over the country. In Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, the landlords who had fled from villages in the wake of the mass peasant upsurge, did not dare to come back even after the police repression was launched against the guerrillas. The struggle still continues in the many states and parts of the country even after it was massively repressed fifty years back. Now, the movement is much stronger than before and has successfully liberated much wider area, thus becoming the biggest security threat for the Indian ruling classes as spoken by our previous Prime Minister. Also, the Naxalbari movement was not just against economic oppression, but also had its own cultural implications specifically in the field of art and literature. The movement tried to bridge the gulf between two different caste-class realities — the reality of the city bred middle class poets, and that of the tribal, Dalit poets of the countryside. This cultural encounter between two different realities divided by rich and poor; high caste and low caste; rural and urban, came face to face resulting in the integration of the urban activists into the struggle of the oppressed masses. This integration happened when the urban bred young people rejected the colonial education system, and their middle class ethics. The urban youths sacrificed their comfort zones, and countered the knowledge system in which they were born and brought up. But the process of integrating with the masses was not an easy task. The uneasiness involved gave rise to a style of literature written in deep turmoil and agony. The process of self-transformation of the middle class-caste youth involved perceiving the social reality from the worldview of the masses.

Similarly, understanding of the contradictions in Indian society, aims and objectives of the Naxalite movement reverberate in the Dalit Panthers manifesto. Dalit Panthers in their manifesto explain the root causes of the persistence of caste, and how it has been reworked to further the exploitative interests of the imperialist powers, and their agents in India. The manifesto clearly states:

“Due to the hideous plot of American imperialism, the Third Dalit World, that is, oppressed nations, and dalit people are suffering. Even in America, a handful of reactionary whites are exploiting blacks. To meet the force of reaction and remove this exploitation, the Black Panther movement grew. From Black Panthers, Black Power emerged. The fire of struggle has thrown out sparks into the country. We claim a close relationship with this struggle. We have before our eyes the examples of Vietnam, Cambodia, Africa and the like.” (Dalit Panther manifesto)

Dalit Panthers not just revolted against caste oppression, but also against the semi-colonial structure by targeting the corrupt parliamentary system, organising workers to shut down factories, and boycotting elections in Bombay. Apart from the Dalit Panthers, it was only the revolutionary Naxalites who broke the myth of an independent Indian nation.

For the Dalit Panthers:

“The struggle for the emancipation of the dalits needs a complete revolution. Partial change is impossible. We do not want it either. We want a complete and total revolutionary change. Even if we want to move out of the present state of social degradation alone, we will have to exercise our power in economic, political, cultural fields as well. We will not be satisfied easily now. We do not want a little place in the brahmin alley. We want to rule the whole country. We are not looking at persons but at a system. Change of heart, liberal education etc. will not end our state of exploitation. When we gather a revolutionary mass, rouse the people, out of the struggle of this giant mass will come the tidal wave of revolutions. Legalistic appeals, requests, demands for concessions, elections, satyagraha – out of these, society will never change. Our ideas of social revolution and rebellion will be too strong for such paper-made vehicles of protest.” (Dalit Panthers manifesto)

This new awakening in the dalit masses and the glorious background of Naxalite movement led to the emergence of the militant literary and social movement led by the Dalit Panthers. This was the first time dalit movement took an anti-establishment stand.

“The literature of revolt vowed to take revenge for the centuries of oppression: it sprang up on notice boards, in slums, in small magazines and posters… the Bhagwad Gita burnt; campaigns to break the practice of untouchability in various forms were organized… On 5 January 1974, in a mammoth rally in Worli, Bombay, the Panthers called for the boycott of the forthcoming Lok Sabha by-elections… they supported the strike of the textile workers going on then. Hearing the call for boycott, the Shiv Sena attacked the meeting… In protest, the Dalit Panthers organized a big morcha on 10 January, which was again disturbed by Shiv Sena. In the police firing, one young poet, Bhagwat Jadhav, was killed. After this, riots broke out between Panthers and the Shiv Sena in Worli, in the heartland of the textile workers’ chawls. For over two months the fighting raged between the two groups.” (Anuradha Ghandy, Scripting the Change)

The Dalit Panthers like the Naxalites confronted state repression, upper-castes private armies, and ruling class goons. But this militancy of the Dalit Panthers did not last long as the leadership fell prey to the ruling class co-option and containment. By 1979, Dalit Panthers group got splintered into nine factions led by their self-styled autocratic leaders. Though, not all groups got co-opted in the mainstream politics. On the other hand the Naxalites smashed the barriers that were erected by the dominant ruling classes that prevented people from uniting against their common enemies. The movement not only broke the caste hierarchies by bringing people from all the section of the society together, but also led the movement of gender equality and democratization of the Indian society. In all parts of the country which were engulfed by the movement, revived the popular folk songs, dances, arts, and created a revolutionary culture which speaks of the values which Ambedkar wanted to establish. Though the rebellion was crushed by the dominant ruling classes in some states, but the rupture that was brought in the Indian political and cultural system continues even now. The present maoist movement in India is the spreading of the same “spark that set the prairie fire”, that is, the Naxalite movement. It has been 50 years since the Naxalbari movement, and the movement has now spread across many parts of India. So far we have witnessed that the movement has won the support of exploited masses to an extent that they are ready to sacrifice their lives for the establishment of an egalitarian society for all. It is equally important to point out that this is the only revolutionary communist movement in India that has been constantly developing and growing even after constant state oppression on it since its inception. Looking at the present state in India with it’s self-proclaimed ‘democratic’ status, a claim which rests on invisibilizing and erasing the thousands of dissenting voices growing every day and every minute in the country, it becomes imperative on our part to realize and acknowledge the significance of the suppressed and gagged voices, and become a part of them, instead of conveniently brushing them under the national carpet. The task at hand requires that people facing oppression instead of closeting themselves in class and caste categories, and thereby alienating themselves from each other, begin to unite together and work to ensure that there be equality for all – a fight geared towards ending the reign of Capitalism, which thrives on these divisions, co-opting and absorbing all oppositional voices. Dalits becoming capitalists for individual gains, garnering benefits at their own individual levels, and thus, in effect, they becoming a part of the oppressive structure are a case in point. Looking at the history of the Naxalite and the Dalit Panthers movement, and the art generated by these movements, we can while on the one hand begin to learn the importance of uniting against the hegemonic forces in society, on the other hand, engaging with their literature, can also enable one to unlearn all the class and caste prejudices one is born into and which makes us the interpellated subjects we are. It is pivotal to keep in mind Bhagat Singh’s revolutionary call for change, and remember that there is not one, but several Naxalbaris burning in India, and the moment requires that we don’t let that fire die.

Sourabh Kumar is an Independent Researcher, Democratic Rights Activist, Former Assistant Professor of English in Ram Lal Anand College, Delhi University.

REFERENCES

Banerjee, Sumanta. India’s Simmering Revolution: The Naxalite Uprising. London: Zed Books. 1984.

Ghandy, Anuradha. Scripting the Change: Selected Writings of Anuradha Ghandy. New Delhi: Daanish Books. 2011.

Ghosh, Kumar Suniti ed., The Historic Turning Point: A Liberation Anthology. Calcutta: S.K. Ghosh. 1992.