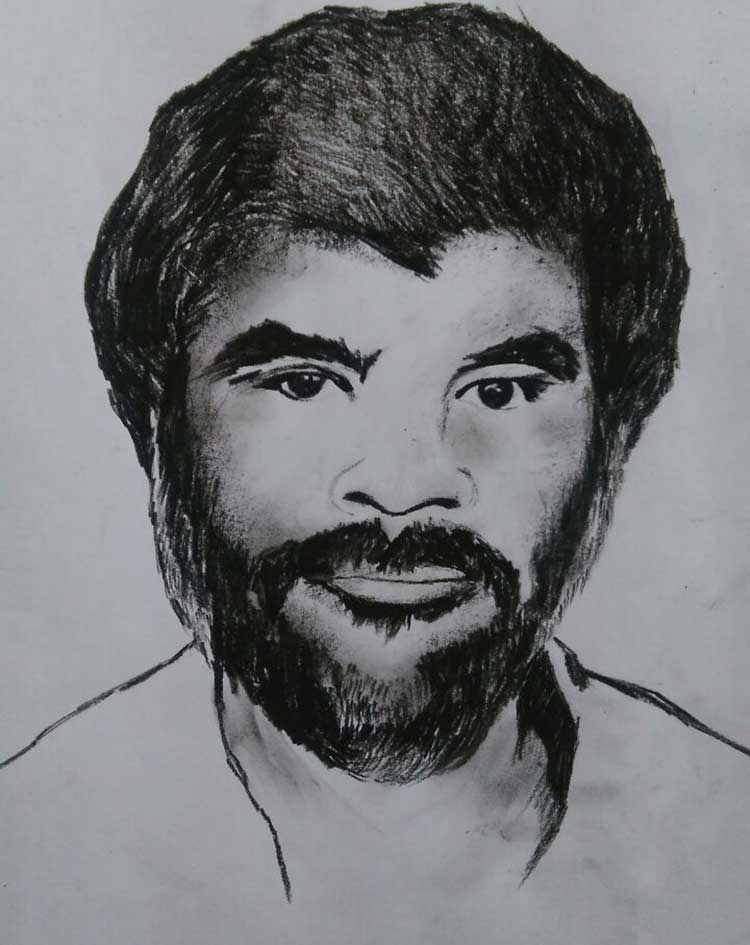

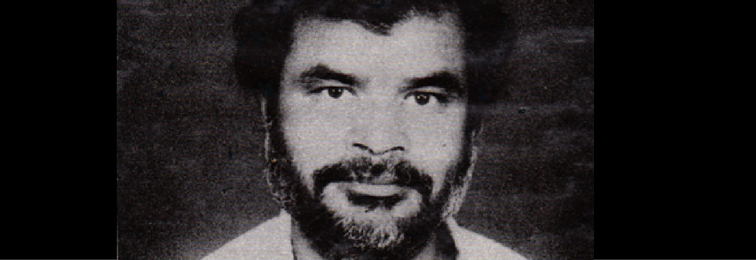

One of the most prominent people in the contemporary labour movement of India, Shankar Guha Niyogi, lost his life for the cause three decades ago. From the time he began his work in Chhattisgarh in the nineteen sixties until his martyrdom in 1991, he led innumerable class struggles. He was the prime mover of a new stream in the labour movement – this stream did not confine itself to eight hours of a worker’s daily life, it did not limit itself to demands for better wages or bonuses or responses to chargesheets; rather, all aspects of the 24-hour day of a worker’s life (health-education-housing-culture-sports-prohibition of alcohol-liberation of women-the historical responsibility of workers towards other exploited classes of society) were part of the agenda of the union, the goal was nothing short of the transformation of society.

His originality lay in the creative application of the ideas of Marx-Lenin-Mao on the ground in Chhattisgarh. The politics of “sangharsh aur nirman” (struggle and creation), initiated by him, was a notable addition to the ideas of scientific socialism. Niyogi was a trailblazer in both the theory and practice of involving the working class in the the movement to transform society by establishing their leadership in the struggle for people’s liberation.

And yet, within just three years of Niyogi’s death, the leadership of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha lost its way. The CMM split into two parts over disagreements about his ideals and the movement, for which Niyogi and sixteen brave workers gave their lives, entered a precarious situation.

I spent eight years in Chhattisgarh. I was the spokesperson for one of the opposing sides in the intense conflict over ideology within the CMM since 1992. After the break up, I was the main organizer for one of the groups, CMM-Niyogipanthi. So I may not be the right person to answer the question of what went wrong, since I will not be able to respond from an impartialstandpoint. I will probably end up taking sides even without wanting to. However, here is my take on the subject in the interests of a wider understanding of what really happened.

The Chhattisgarh movement got a lot of popular support after Niyogi’s death. The anger of the workers of Bhilai-Urla-Kumhari-Tedesara-Dalli-Rajhara was at a boiling point. With the help of allies the workers could have, at that time, shut down the factories and had their demands met. The government could have been forced to punish the murderous capitalists. But the leaders, stunned by the sudden death of the person at the forefront, lost their bearings. That is why the spontaneous 7-day industrial strike was abruptly halted. Instead, there were fasts, meetings, processions, protests by Mrs. Guha Niyogi, symbolic courting of arrest for a day and so on. There was a lot of publicity, but no direct pressure on the capitalists.

Here it is necessary to provide an overview of the organization of the CMM. Before the 1990 Bhilai movement, the red-green banner was mainly active in the Dalli-Rajhara, Danitola, Ari Dongri, Bandi Dongri, Hirri, Baradwar, and Rajnandgaon area. CMM was a loose umbrella organization for the different labour unions, it had no formal membership. Members of the red-green unions and active village leaders were considered CMM members. The only office-bearer was the President Janak Lal Thakur. However, the need for democratic practices within the organization was strongly emphasized. Every wing took decisions through a democratic process and Comrade Niyogi, along with Janak Lal, maintained contact with each wing.

With the Bhilai movement in1990, the CMM organization grew appreciably and people felt the need to build a central committee. But one attack after another from the state apparatus left no time for that. In 1991, after Niyogi received hints of a conspiracy to kill him, he recorded his thoughts about the organization and the movement in a secret cassette. He named nine activists who were in the forefront and whom he thought of as suitable members of a central committee – Janak Lal, Ganesh Ram, Nilratan Ghoshal, Phagu Ram, Bhimrao Bagde (five labour leaders) , Sheikh Ansar (youth leader), Dr. Saibal Jana, Dr. Punyabrata Goon, and Anoop Singh (three intellectuals, the first two doctors at the Shaheed hospital). He also suggested that leading labour activists be included in the central committee through democratic election.

After listening to the cassette, the workers unanimously approved the nine-member committee. But the committee could not become fully functional because of practical problems. The Shaheed hospital had only two doctors at that time, both members of the central committee. Only one of them could be available at any point for committee work. Also, I had already begun some very important work – in order to give Niyogi’s thinking wide publicity, I set up the “Shaheed Shankar Guha Niyogi Smriti Raksha Samiti” under the CMM publications arm, the Loksahitya parishad. One after another we released printings of Niyogi’s previously published writings, his unpublished writings, and evaluations of his work. There was also the job of being the CMM spokesperson – meeting journalists, talking to visiting leaders and activists of allied organizations, and maintaining contact with them. Moreover, Sheikh Ansar and Bhimrao Bagde were in primary charge of Urla and Kumhari, respectively. As a result, the Bhilai leadership was provided by just three people – in the worker areas by Cde. Ghoshal and, ten kilometres away, at the Hudco colony by Janaklal and Anup. The Dalli-Rajhara labour union was the source of funds for the movement. As leaders of that union, Janaklal and Ganeshram were “more equal among the equals”.

The workers wanted a militant movement. So from time to time a militant program was announced such as a gherao of the owners’ residential area Nehru nagar, obstruction of Murli Manohar Joshi’s ekta yatra, a call for an indefinite “fill the jails” or direct action. But each time, Janak and Anup, reassured by promises from the police and government, withdrew the agenda without consulting the workers. Looking back, I can see that the journey from class struggle to class compromise began right then.

The workers grew restive, they began to raise the slogan “do or die”. The leaders were at a loss. That is when (February, 1992) a friend of the Chhattisgarh movement since 1977 and a close political associate of Com.Niyogi, Com. Prafulla Chakrabarti, now known for the Kanoria jute workers struggle, suggested an “agenda for the great struggle”. This proposal was based on a 1990 speech given by Com.Niyogi. (In later years, the Kanoria great struggle was modelled on this agenda.)

The labour leaders discussed the proposal. Then, after extensive discussion at every level of every branch of the organization, the agenda for the shutdown of Bhilai was adopted. More than a thousand worker mukhiyas, divided into 29 teams, spread the word in more than 4000 villages in five districts and built up unprecedented worker-farmer solidarity in support of the Bhilai agitation. The Bhilai agitation was no longer just a workers’ movement, it was transformed into a movement for people-centred development in Chhattisgarh. It was decided that on 28th May, 1992 five lakh people would shut down Bhilai. The previously mentioned central committee worked well only during that period from February to May. By then two new doctors had joined the hospital, groups of doctors came from Kolkata to help. As a result, the two of us, doctors on the central committee, set aside our hospital duties and dived into the work of the movement. In this phase, everyone except Anoop Singh was on the same page regarding the Bhilai stoppage agenda. (Anoop opposed this plan at every meeting of the central committee.)

The authorities were alarmed at the extensive preparation for the Bhilai shutdown and additional police personnel were brought in from other districts. But at the last minute, based on verbal assurances from the industry minister Kailash Joshi, Janaklal and Ganeshram withdrew the plans for the shutdown of Bhilai on May 25th. And yet, just a few hours before that, an assembly of the extended central committee had decided not to withdraw the agenda without a written promise of change. The whole organization was outraged at the undemocratic action of these two leaders.

A struggle between two lines of thinking began in the central committee – democratic centralism versus just centralism. Everyone other than Janak, Ganesh and Anoop was in favor of democratic practices. We raised a demand in the central committee for self-criticism by the leadership and a return to the previously planned agenda. The members of the central committee were divided on this question – half were in favor of self-criticism and the rest were opposed to it under any circumstances. This standoff continued.

On 25th May, almost 50,000 people assembled in Bhilai. And yet, not even a procession was organized as a show of strength. 25th May 1992 was the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Naxalbari uprising (when the date of the shutdown was set, people did not realize this).The CPI(ML)-red flag put up posters all over Bhilai for this occasion. There was no procession because of fears that the Naxals would infiltrate it and incite violence. People from the villages returned disappointed. Only four thousand or so unemployed workers and their families began a sit-in in Bhilai.

The sit-in agenda that was taken up under pressure from the workers lasted from 25th May to 1st July. It was decided that the sit-in would continue until demands were met. Instead, our worst fears were realized – because of the absence of the threat of a Bhilai shutdown, the demands were not met despite repeated tripartite meetings in Bhilai-Indore-Raipur.

Each day of the sit-in cost more than 25 lakh rupees and funds were running out. On the other hand, the blazing sun, rain and thunderstorms under the open skies of May and June drove many workers back home. Even then, from 2500 to 3000 workers stood firm, they would not return without getting what they wanted. In order to break this stalemate, the leaders suddenly decided to block the railway line on July 1st. What should have been an undertaking for 3 lakh people was taken up with less than 3000. The machinery of the state launched a barbaric attack to finish off the CMM. Almost 200 labour leaders and mukhiyas were imprisoned on various charges. A curfew was imposed for seven days and section 144 remained in place for two and a half months.

After the shooting, Nilratan Ghoshal, Sheikh Ansar and Bhimrao Bagde were arrested. Two other central committee members, Janak and Anoop, went into hiding. (Phagu Ram was not active in the committee right from the beginning, he preferred spending time with his art.) Ganesh and the other Rajhara leaders were terrified. Dr. Jana and I got busy working to revive the Bhilai organization starting July 2nd. As doctors we were relatively safe from the police. We got significant help from Niranjan Lal Yadav, a CMM leader in the cement industry. Like the legendary phoenix, CMM was reborn from the ashes. There was a massive gathering in Bhopal on 3rd September, on 16th September the authorities were forced to withdraw section 144 and, on September 28th, the first anniversary of Niyogi’s martyrdom, there was a tremendous display of the triumph of people power over brute force. All of this happened in the absence of the top leaders, but it happened in a streamlined manner because by then we had set up a committee with the Bhilai mukhiyas and established democratic procedures for making decisions.

The leaders that were in hiding opposed pressure tactics other than meetings, processions and gatherings – they were afraid of more shootings. We argued in the central committee that class struggle was the only way to get our demands met. Janak-Ganesh-Anoop considered the democratic framework that we set up in Bhilai an attempt to undermine their leadership. We were made to return to our hospital duties, Com. Yadav was forced to go back to Balodabazar. And no central committee meetings were convened after 1st October 1992. I was relieved of all organizational responsibilities.

As long as the central committee was active, we voiced our support for democracy and class struggle in the committee meetings. Now we lost the opportunity to speak there or at the meetings of mukhiyas. The Janak-Ganesh-Anoop coterie took all the decisions since they were in charge of the funds.

But we did not give up. On 14th February 1993, we opened a clinic in Bhilai to stay in touch with the workers. Dr. Jana and I stayed in Bhilai on alternate weeks. And we took this opportunity to communicate our views at the same time. I can reveal now that I was the centre of a secret group of Bhilai workers who wanted democracy in the organization and who wanted the Bhilai movement to proceed on the path of class struggle. My companions called for an agitation demanding the release of prisoners. They wanted to use the elections to move the struggle forward. I was behind them. The leaders in power were aware of my role in this and began the effort to oust me from the organization right from 1993. The workers kept these efforts in check.

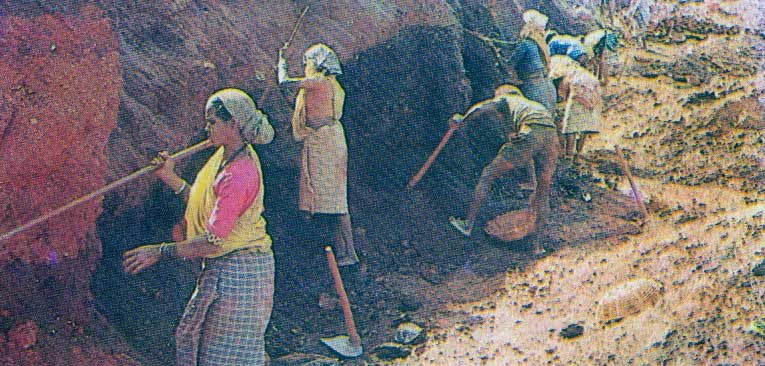

The leaders got their chance in June 1994. On 31st May, the leaders signed an agreement with the management of the Bhilai Steel Plant to mechanise the Dalli mines. Workers had blocked mechanisation since 1978 under Niyogi’s leadership, a semi-mechanised process was in use because of pressure from the movement. Other doctors from the Shaheed hospital and I opposed this agreement since it would result in more than half the workers losing their jobs. Com. Asha Niyogi also spoke openly against this agreement at a public gathering on 3rd June, the Shaheed divas of Dalli-Rajhara.

The leaders were unable to refute our arguments from an ideological standpoint since everything we said was supported by the writings of Com. Niyogi. So they brought up a diversion setting Chhattisgarhis against non-Chhattisgarhis. I was accused of collaborating with AITUC to bring out a leaflet criticizing the agreement. On 21st June, in my absence (I was in Kolkata on family business), some mukhiyas from Dalli-Rajhara called a meeting and suspended me from the hospital. I made a written demand that I be allowed to speak at a meeting of mukhiyas from all branches of the CMM. I was not given that opportunity. I then took what I had to say directly to the membership of the CMM in a six-page leaflet. This pushed the the leaders’ tolerance over the limit and they decided to expel me. On 13th July the Bhilai mukhiya meeting rejected the expulsion, the Balodabazar and Champa branch organizations also rejected it. Despite that, the leaders put out a press release saying that Dr. Gun has been expelled.

My companions did not leave the organization for me, they continued the ideological struggle within. On 18th August, the leaders came to Bhilai with police protection and announced the expulsion of Nilratan Ghoshal and several of my other associates.

We had wanted unity, we had wanted Niyogi’s ideals to be championed by the CMM. But now we were left with no choice but to form a parallel organization. The Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha (Niyogipanthi) came into being. This name was chosen because we wanted to uphold Niyogi’s ideals of democratic centralism and class struggle within the CMM.

On the one hand, there was the financial strength of the CMM, popular support gained under the pretext of nationalism, help of the police and authorities, and good relations between Janak Lal and the Chief Minister Digvijay Singh. On the other, there was CMM (Ni) trying to keep Niyogi’s ideals alive. The battle was uneven.

In the meantime, an important leader on our side (who will remain unnamed) raised doubts about the red-green flag. He gave as his opinion that a labour union should be free of politics and flags. He asserted that there should be no agitation, and that our only option was to talk to the owners and pocket unions and get back to the factories. Some of our associates, confused by this, became agents of the owners. The larger segment of the group was rendered inactive by the disagreement between me and the other leader. (Indian workers are still very dependent on leaders. Who knows when we will get rid of this feudalistic mindset!)

It will take a long time to build up a movement again in Bhilai. CMM has abandoned the path of struggle, they believe in getting their demands met through discussion. (The CMM leaders say that Niyogi was not a revolutionary, he was a Gandhian.)

But I still hold out hope. The blood of the martyrs has not been shed in vain. As exploitation increases, the Bhilai movement will grow strong again in order to fight back.

One might ask why things turned out this way. I think the reason for this failure was the absence of a central role for scientific socialism after Niyogi. Should we then say that Niyogi failed? Before criticizing him we must first understand the historical context of his work. His pioneering organization and movement was created with uneducated or poorly educated, unskilled, first generation workers (who came from the villages and among whom a feudalistic mindset was very strong). He came to Bhilai to look for the next line of leaders but lost his life within a year. And yet, with the work that he did in just this one year, and all our efforts that have followed, Bhilai has undoubtedly made valuable contributions to the fight for social transformation in India.