It says a lot that societies who are still part of what is rather weakly called the free world could do this. Technology, viewed as emancipating and rewarding, can actually introduce different chains and shackles, becoming repellent and self-defeating.

The field of privacy is one such precarious area, permanently assailed by the chest-thumping innovators. Privacy, that intangible phenomenon Mark Zuckerberg, at one point, thought had been abolished as a social norm, less by the vague controls of Facebook than by the volition of users to “share information”.

The world of surveillance has gone total and, of greater concern, become totalising. Social media details shared, distributed and monetised is but one aspect of this world with withered privacy. Products sold to the general public for use – take the talking doll “My Friend Carla” – invite a data accumulating entity into the home. The doll’s manufacturer, Genesis Toys, insists on ensuring “that our products and services are safe and enjoyable for our customers.”

That particular doll, ironically enough, has concerned those in the business of surveillance, a form of unwarranted competition to those who are in the know. Jochen Homann of Germany’s Federal Network Agency insists that the country-wide ban, which has come into force, was designed to “protect the most vulnerable in our society.”

And what, exactly, was so irksome about this intrusive creature? For one, it relays a child’s audio question through wireless means to an app on a digital device. This question is rendered into text which is then used in the conduct of an Internet search. An answer is generated, and verbalised through the doll.

“Items that conceal cameras or microphones and that are capable of transmitting a signal, and therefore can transmit data without detection,” observed Homann stridently, “compromise people’s privacy.”

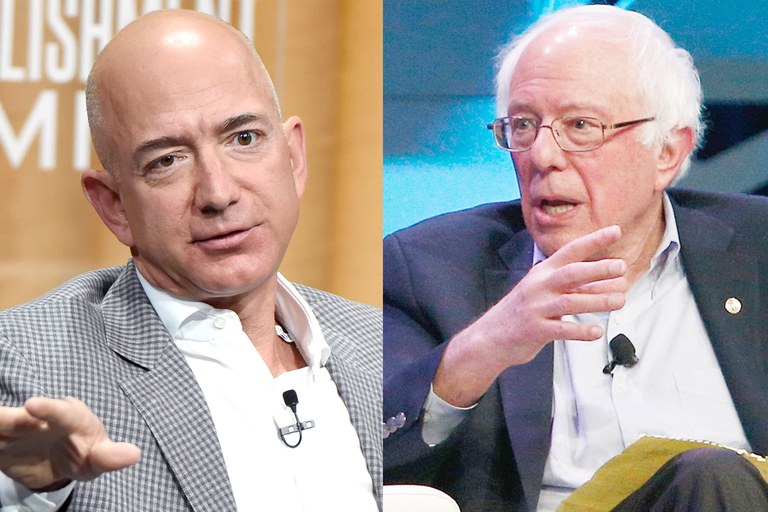

Dolls connected to the internet; sex toys linked to the world wide web; and, of course, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos haunting you in the home with Alexa, a talking digital assistant connected with the speaker Echo. Alexa, this happy searching missionary, scouring and gathering intelligence for that weighty mother ship, Amazon, all used in the name of profit and customer experience.

For one thing, Alexa shows how sources of inspiration, entertainment and variety have shifted. Like the search-hungry connected doll, Amazon’s Alexa, after being woken from digital slumber via Echo, conveys material through Amazon’s servers, where the audio is analysed. The command is thereby sent back to the Echo device. Both the voice audio and the response, is stored and linked to the user’s account.

Amazon’s terms of use describe Alexa as streaming “audio to the cloud”. This takes place “when you interact”. The main company duly “processes and retains your Alexa Interactions, such as your voice inputs, music playlists, and your Alexa to-do and shopping lists.” With the creation of the voice profile, Alexa duly makes use of the recordings “to create an acoustic profile of your voice characteristics. This allows Alexa to call you by name and personalize your experience.”

Brad Stone of Bloomberg finds it thrilling, using Alexa’s speakers to “play music and news, tell jokes and get the weather.” Obviously a bit short in the department of imagination, is Stone. But even he admits that privacy is very much for the chop. Volumes of data are conveyed to parent companies via Amazon Echo and Google Home.

For all that, there are the converts who use decidedly benign, if not neutral language, in describing these “in-home voice assistants” who are advertised as non-corporeal butlers equipped with the Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Reports of the Echo and Google Home’s ability to spy on you,” writes Eric Ravenscraft in myth-busting language for How-Ro-Geek, “have been greatly exaggerated.” For one, such devices might be in a permanent listening mode, but not recording. Comforting, even if of the cold variety.

There is another cold comfort as well, the sort we can get from bumbling and privacy loathing intelligence services: there is simply too much in terms of what can be recorded or listened to on either Google Home or the Echo. Surfeit and plenty might just save us.

Ravenscraft is, however, privy to an important point of data storage, a facility that can be tapped into, be it through the prying eyes of government officials, or the venturing hack. Amazon’s storage of recordings might well become a source of interest to the authorities, a point made with exemplary and troubling effect by Edward Snowden in 2013. “Naturally, if Amazon is going to store recordings of even some of the things you say in your home, you might want to know if the company is going to turn that over to the government.”

Bezos has been spending time reassuring consumers that, when it comes to privacy, his company is up with the times. Echo is “no different from your phone” but when hitting “the mute button on Echo, that red ring comes on that says that the microphone is turned off. That mute button is connected to the microphone with analog electronics.”

Such technological developments are less innovations than rampages, conditioning human approaches to communication and the way information is shared. Desensitised as subjects, humans are set to become mere sets of units and data themselves, their behaviour a historical set to be analysed, exploited and even predicted. The need to have an entrenched, global regime of privacy protections, far from being less important, is more vital than ever.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]