Second of three interviews from the cradle of the revolutionary uprising

Aneek, an independent, radical Baanglaa monthly from Kolkata, India, in its 53rd years of publication, interviewed three leaders of the Naxalbari Uprising. The leaders with working class background were organizing armed struggle of the poor-landless peasantry in the Naxalbari region since the earliest days of the revolutionary initiative. Following is Khemoo Singh’s interview, the second of the three, conducted by Arijit and Subhasis from Aneek, and published in the monthly’s May 2017 (vol. 53, no. 11) issue. The interview was conducted in May 2017 at Khemoo Singh’s village home in Siliguri, more than 450 km north of Kolkata. All the interviews were video recorded; and its audio parts were transcribed by Subhasis, and were vetted by the interviewees. None of them denied any part of respective interview. The interview is translated from Baanglaa by Farooque Chowdhury. The first of the three interviews was carried by Countercurrents.org, an e-journal from South India, and Frontier, the radical weekly from Kolkata, on November 20, 2017 (https://countercurrents.org/2017/11/20/aabaar-naxalbari-naxalbari-again/) and December 31-January 6, 2017 (vol. 50, no.26, http://www.frontierweekly.com/articles/vol-50/50-26/50-26-Naxalbari%20Again.html) respectively.

Khemoo Singh: “Seize lands” was our slogan

I’m Khemoo Singh. I was 14-15 years old in 1967. Kaanoo da [mainly spelled Kanu Sanyal], Khokon Majumdar, Keshab Sarkar, and other leaders of the Naxalbari Uprising regularly visited our village, and used to have meetings with the villagers. Those meetings were intense and forceful. We are influenced deeply. Jaail Singh, my father, was a member of the Krishak Sabha, peasant front of the CPM [Communist Party of India (Marxist)]. He joined those meetings. I also attended those meetings as I followed my father.

We actively took part in the movement, which began in early-1967. I was fully involved in all the processions, meetings and in all assaults on houses of jotedaars, rich peasants.

One question, political in nature, haunted me since my childhood: why crops, after harvesting, reach jotedaar’s house instead of tiller’s, why crops don’t reach share cropper’s house; why share cropper comes back home empty handed? I, since childhood, sensed the arrangement unjust. It was a permanent phenomenon that share cropper or tiller was deprived whenever sharing of crop was done on jotedaar’s courtyard. Jotedaar took away all crops on account of credit advanced to the tiller; and credit was again advanced. The issue unceasingly circulated within my head since my childhood. The issue again came up during the 1967-movement.

We joined the newly formed party [Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist)] with much enthusiasm. From its inception, a little part of the party was open; but mostly it was secret. The party was not officially banned before the promulgation of emergency in 1974. However, repressive situation turned so demonic after 1969 that we were forced to go underground in the face of terror the state was resorting to although the party was not banned. We five activists from our village went underground, and joined guerrilla unit of the party.

We carried out a number of guerrilla operations. Following is the brief description of an incident in Maagoorjaan [mainly spelled Magurjan]:

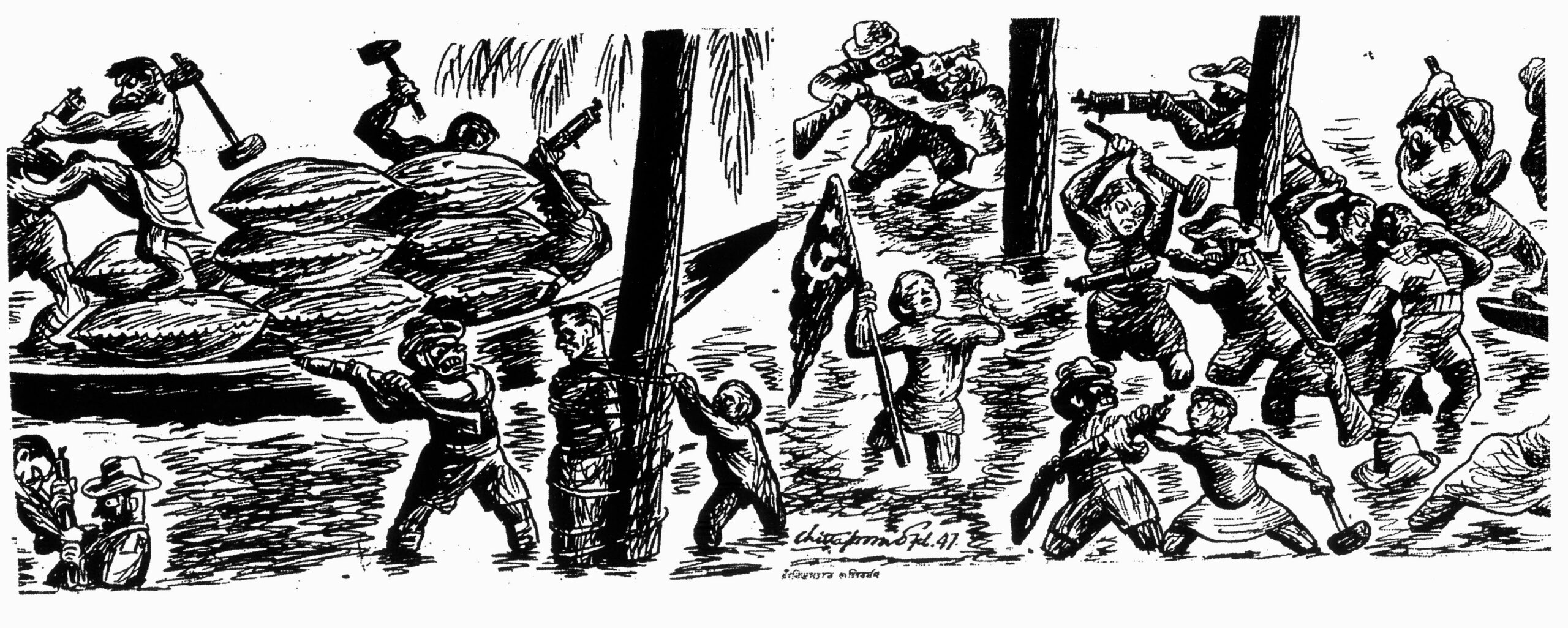

We 11 comrades took part in the Maagoorjaan operation. Six armed policemen were stationed there in a police camp in Maagoorjaan. We made an assault on the camp, and captured six rifles. One sentry of the camp fell dead.

I also took part in the assault on police camp in Beer Sing Jot [mainly spelled Bir Singh Jote]. Enemy bullet speared through head of a comrade. We paid tribute – Red Salute – to the comrade, and retreated with his rifle. Our reconnaissance related to the operation was not adequate. This impacted our planning.

There was a jotedaar at Poolooshkodor in Vaataagheshaa. He united all the jotedaars, and with their united force, made assaults on the poor peasants. A number of poor peasants were murdered by the jotedaar-force. At a later stage, our guerrilla squad annihilated the leading jotedaar in his home. We also organized a number of armed operations in Bihar, and in Dinajpur [then, Paschim Dinajpur district, which has now been bifurcated].

We were in company of Kaanoo da while we were underground. Kaanoo da was apprehended in 1970. Kadam Mallick had the same destination. We, later, in 1971, organized the Maagoorjaan incident. Our entire leadership was in jail during the time. We realized that we needed arms both for defensive and offensive purposes. Comrade Aagnoo Topo and me were in the lead in the operation. Later, comrade Topo embraced martyrdom.

During the time, political commissar and guerrilla commander were in the lead of each guerrilla squad. I was guerrilla commander while comrade Topo was the political commissar.

The small village adjacent to Maagoorjaan was our den. We were following the politics of self-sacrifice. We feared no death.

The police camp we planned to attack was by a rail track. We were crossing the track. The main guard of the camp shouted: Ei toom kon ho? Who you are? Our reply: Haamlog baazaar se aataa hoo, we’re returning from market place. We charged instantly, before he could guess anything. We snatched away his rifle while he was going to charge bayonet on us. It should be mentioned that we were armed only with ghareloo, a sharp locally-made weapon. We had no fire arms at that time. In the face of our swift action, other policemen in the camp couldn’t take preparation to counter-charge us. We captured all the six rifles, and sent those to Beer Sing Jot.

There was a village named Lakkhee [mainly spelled Laxmi] Jot in the area. Three women comrades were staying with us while we were there. We were deputed to the duty of night guard. The female comrades saw police surrounded the area while the comrades were in morning-shift guard duty. The comrades reported the police encirclement. We began planning a counter-measure. Jogen Sing, a comrade from the village I was from, was there. Comrade Jogen is now no more. On that morning, Jogen Singh and me moved to a corner, and began firing from our rifles. One police official, assistant sub-inspector or sub-inspector, named Ganesh Paain [mainly spelled Payn] from the Naxalbari Thana [police station] was there. One of our bullets hit his abdomen. The shot was from my rifle. He felled. The police party began retreating. All of us went away as the encircling police force retreated.

They, the police, later came again, and shot dead three villagers as none of us were found. The villagers were put on a line and fired on. It was a retaliatory step by police. The murdered villagers were poor farmers.

We had to spend a lot of bullets to breach the encirclement. Probably, I have not shot so many bullets in my guerrilla life. One of my comrades and me were walking down through aaeel [slightly raised earthen demarcation line between two crop plots] while the police party opened fire on us. However, we passed away. The police party re-grouped, and charged us. Each of us had one clip of bullets. Our bullets were almost spent. The rifles we were using required clearing of barrel after firing 20-25 bullets. Otherwise, the rifles turned unusable. But, we had not the time to clean rifle barrel. I fired approximately 75 bullets. Our rifles, amazingly, cooperated with us instead of creating trouble. Two, one home guard and one from paramilitary force, fell dead. All of us could go away without getting any hit.

Rifles captured from Maagoorjaan were used in many areas including Lakkhee Jot. We punished jotedaars with these rifles. Jotedaars’ fire arms were also seized using these rifles. Charu da [Charu Majumdar] wrote: People’s Army of the peasantry in India came into existence with the Maagoorjaan incident.

There was a very big jotedaar in Dinajpur. The area was adjacent to the border of Bangladesh [at that time, it was East Pakistan, a part of Pakistan]. His rifle was seized after annihilating him with the Maagoorjaan rifles.

We also attacked a similar big jotedaar in Bihar with the Maagoorjaan rifles. He had two guns. Seizure of guns is not enough. Cartridges of gun enable to use the gun. We also seized cartridges of the seized guns. The jotedaars didn’t have a large number of cartridges. We seized whatever was at hand. We seized all the bullets while capturing rifles in Maagoorjaan.

Gradually stock of our bullets and cartridges began to dwindle. Many of our comrades were apprehended. They had only guns. I was also apprehended with a rifle. I had no bullets. The rifle turned useless. I tried to secure the rifle. I hid it. But, police found out the hiding place.

Police began charging at me. I began to run towards Barajharoo Jote. One of our comrades was there. Police were firing at us and began encircling all of us there. I had no means to carry on resistance. I was apprehended. The incident was around 1975.

I was taken to Karseong after arresting me. Then, I was moved to Siliguri Special Jail. After a few days, I was sent to Burdawan Jail. I was kept at the IB [Intelligence Bureau] office at Lord Sinha Road, Kolkata, for about 15 days before I was again transferred to Burdawan Jail, where I was interned for about a year. Then, I was transferred to Bhagalpur Jail; from there, to Kishanganj; then, to Siliguri, and again to Kishanganj.

Darkest days of the Emergency Rule were passed in Burdawan Jail. We planned to observe the May Day in the jail. The main celebration would be rising of red flag within the jail. We were determined to raise red flag despite all obstacles and oppositions made by jail authority. It was decided that the person first to be brought out of jail cell would hoist red flag. We were the first to be brought out of cell. We raised red flag, and the authority turned bewildered. Then, they sent their force. The force confiscated the red flag we raised. However, our decision to raise red flag was successfully carried out.

We had a very cordial relationship with jail sepoys. They tried to help us. Hence, collecting the red flag, etc. was not difficult for us. Writings of Charu Majumdar reached us within jail.

In my life, the 1967-movement is a phase. Another phase was the underground life. The jail-life is another phase. The underground phase was comparatively longer, spanning from early-1969 to ’75.

Most of our work during the 1967-1969 phase was carried out openly. We passed about a year in underground life with Kaanoo da. We began to lead ourselves after Kaanoo da was apprehended.

A few adventurist ideas prevailed among us during the period. We identified beastly jotedaar to be annihilated. We carried out the action. However, we failed to mobilize wide section of the masses due to this method of action. Virtually, we tried to carry on action on behalf of the masses while staying isolated from the masses.

Many of us used to contemplate the method: what’s going on? Later the line of work advised to us was: hit and stay, hit and rush. We practiced the line also for quite some time.

In 1967, distribution of land, etc. work was done along with seizing of guns. After 1967, there was absence of any work with agrarian program; there was only annihilation work.

Let’s assume, in 1967-’68, we went to residence of a jotedaar to annihilate him. There was paddy stored in his golaa, barn. All poor peasants were called to assemble there; and the paddy from barn was distributed among the assembled peasants.

The village I’m from was of a certain character: it was den of all leaders of the revolutionary movement. Kaanoo da used to visit the village regularly. Brute jotedaars in our village fled away. The rest, willing to stay in the village along with the poor peasantry, knelt down to us, and said: “We are surrendering our guns to you. Please, don’t kill us.” Many of the medium, small jotedaars followed the same approach. This also happened in villages surrounding ours.

I recollect the incident of Lakkhan Singh [mainly spelled Laxman]. A huge number of villagers assembled on a school play ground. He, Lakkhan, came to the assembly, and said: “You, please, take away all my belongings including my gun; but, please, spare my life.” In our village, 11 guns were collected with this approach. We distributed guns and paddy among the villagers.

We succeeded in seizing vested land. A part of this land was distributed among the poor peasants. This happened in Booraaganj [mainly spelled Buraganj]. We had a slogan: Seize lands of jotedaars and the land retained by big landowners under false title. We were moving toward implementing the slogan. However, we could not implement the slogan on a large scale. I heard from comrades that that type of land was distributed in Beendeshwaree [mainly spelled Bindeshwari]. I was not present there. I also heard similar development in Haateegheeshaa [mainly spelled Hatighisha]. With the distribution of land under false title the poor peasantry joined us enthusiastically. The question of armed struggle arose as it appeared that arms were needed to keep hold on the distributed land.

The issue of returning back goods and properties of the poor mortgaged to rich farmers and usurers was coming up in our movement. It was developing towards the program. But we were attacked before the program developed fully. We were reaching the poor peasantry with the program; and they were getting acquainted with the issue.

We couldn’t continue the 1967-’68-struggle for a long time. Set back in the Naxalbari movement is, probably, the cause of absence of any new movement in Naxalbari despite spreading of its impact all over India. Efforts to reverse the set back were not also that much successful.

During the Emergency Rule, there is not a single village in this region, which has not experienced police arresting all the poor peasants connected to the movement. Even, those distantly related to the movement were also arrested. These peasants were released from prison in 1977. Those arrests were workers required for organizing and directing movement.

There’s a wide difference between the pre-1967-movement and the movement in 1967 and its aftermath. During the first movement, the issue of class struggle in the rural areas was not clear at all to the poor peasantry. On the one side, it was the jotedaars while the poor peasant masses were on the opposite during the period. The poor peasants could easily be made realize: who’s your enemy? It’s the jotedaars. So, we have to fight out the jotedaars.

The poor peasants’ continuous assaults on the jotedaars reduced the number of the jotedaars and their commanding force on the broader society. The huge difference in ownership of land was also not intact as of the past. Hence, today, a poor peasant can’t identify his enemy if he is asked to. At that time, the picture was clear. Today, the issue is not as clear as like the past. This makes organizing the poor peasantry quite difficult today. Today, the poor peasants can’t be organized only on the basis of land question.

However, condition of the landless peasants today is the same as of the past. At that time, the land question pulled landless in the movement. It’s a fact that the question of having no land by the poor peasants has not been resolved. With the existing condition, the issue will not be solved. Hence, there’s no reason for failure in mobilizing them. The problem is: who will mobilize them? Still today, the peasants don’t get fair price to their crops; still today, they find prices of all implements and inputs for farming are increasing.

Rather, it can be claimed that there are many other issues, which are equally important as the land question.

I had the opportunity to meet Charu Majumdar only once; and that meeting was in his home. I went to him with another comrade’s work. Charu da was to deliver the job. One female comrade was with me. Charu da asked us to sit. We heard him telling his family members in his home: “They are from a village, the rural people, probably, they need food.” That was the single time I met him. I never had any opportunity to sit with him in any meeting.

I once met Saroj Datta [mainly spelled Dutt]. There’s a place named Chopraa in Dinajpur. Saroj Datta was there in a shelter with us for a week. He was a comrade in real terms. The main discussion centered on explaining Charu Majumdar’s line. That was in 1970. He used to tell us about guerrilla action. At that time, the Party went underground. He came to Dinajpur to have clandestine meeting with us. During the time, we were with Deepak Biswas [mainly spelled Dipak], Shaantee Paal [also spelled Shanti Paul] together.

At that time, Mahaadeb [mainly spelled Mahadeb] Mukherjee was a senior leader. We saw him, a person with a big physical appearance; comrades felt overwhelmed. But, he was a bit shaky despite the big appearance. Once he told us: “I’ll be identified. So, we’ll pass by pretending that I’m sick. You’ll carry me. That will make them ignore a sick person.” We almost carried him across the big bridge on the NGP. He made a hue and cry by setting fire on blanket while he was in the Intelligence Bureau headquarters at Lord Sinha Road.

And, I stayed closely with Paanjaab Rao [mainly spelled Punjab], Keshab Sarkar and Jangal Shaaotaal [mainly spelled Shantal]. Man like Jangal Shaaotaal is rare; a very plain and simple person he was; an ideal peasant leader. Such a leader is needed now as was required during that time. We got involved with a movement in a dairy firm after our release from jail. The firm was locked out. We joined the movement to reopen it. Police resorted to firing to break down a mobilization in the movement. It was around mid- or late-1980s. Police was firing indiscriminately, and Jangal Shaaotaal was standing steadfast amidst the firing, and was shouting at police: “Chaalao golee”, “Fire, fire at me.” I saw what a hellish situation! On the opposite side, the police officer turned bewildered as he saw a person standing in front of firing line and shouting Chaalao golee while rest of the mobilization was running away. Jangal Shaaotaal was standing steadfast. Police then came forward and said with a humble tone: “Jangal Baaboo, aap vee hat jaaiye”, Mister Jangal, you also move aside”. Jangal again shouted: “Nehee, haam nehee hategaa, chaalaao golee”, “No, I shall not move back, fire”. That was a moment of courage of a leader!

Paanjaab da was such a man, who stood by the poor peasants, always fought on by the poor peasantry during underground life. Paanjaab Rao had communist conscience, which means always alive with thoughts for social change and revolution. He kept this thought alive till his last breath. The history would have been different if today there is a Paanjaab Rao, a Jangal Shaaotaal.

Khokan da was also a senior leader. These persons came through a long movement. They embraced many hardships. They organized the poor peasantry, mobilized them in struggles, and led them. The present space gained by the poor peasants in this area is due to the big movement of the peasantry, the movement led by Khokan da, Keshab Sarkar, Jangal Shaaotaal, Kaanoo da, Paanjaab Rao. Today the poor peasantry in this area is having many rights compared to the past, and that’s due to the movement these communist leaders organized while they sacrificed everything. Today’s developments wouldn’t have been possible had there not the 1967-movement.

Kaanoo da is a person with communist conscience. We were puzzled when we learned the last act by a person like Kaanoo da. Kaanoo da used to trust us too much. He used to tell us: “Thou are engaged with so much work, but are not succeeding in building up an able leader in the area!”

Farooque Chowdhury translates from Dhaka.