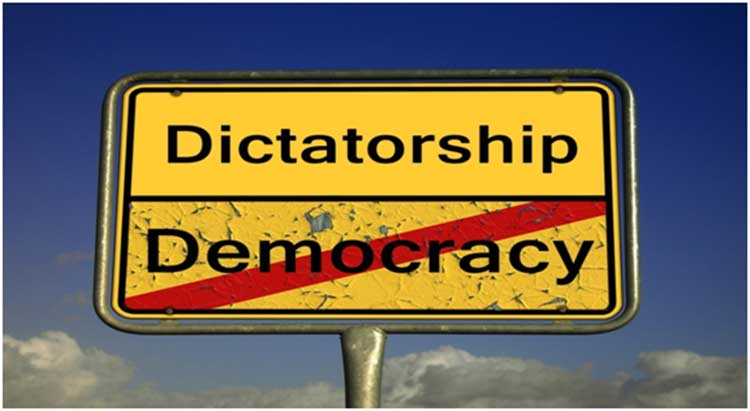

The North Shore of British Columbia is approaching yet another four-year election cycle in October 2018. But in 2014, out of a total population of some 265,000 residents, only a paltry 32,000 or 25% of the actual registered voters bothered to cast a vote for who would guide the course and direction of Canadian society along its shores; thereby calling into question the interdependence between the people and their rulers, upon which Democracy is said to be based. British Columbia is among the lowest in voter turnout in Canada. Election experts say that when voter rates dip into the low 20’s it becomes a democratically dangerous situation; with governments easily turning into autocracies, benevolent dictatorships or something worse. The problem with Canada, British Columbia and the North Shore is that they’ve never chosen any kind of compulsory voting system, nor have they yet put in place even a proportional representation system.

Yet when so few registered voters bothered to vote in 2014’s North Vancouver City, North Vancouver District and West Vancouver District’s elections questions began to be privately raised as to whether or not the results should have been declared null and void and a re-election held until some mutually agreed upon appropriate minimum percentage of voters finally decided to exercise their democratic responsibility and civic duty to actually vote.

Such abysmally low voter turnout figures raised still other questions concerning whether the North Shore’s citizenry, perhaps increasingly like Canadians everywhere, have cynically adopted more of a Why Bother attitude towards voting when they don’t feel the government is a truly democratic one that represents their views or fails to genuinely listen to and respond to their real needs and wants. Or perhaps the reason they don’t vote is because they just take for granted that what is happening in places like the North Shore with over-development, population explosion, grid lock traffic congestion and sundry other related issues always seem more like virtual done deals that have nothing to do with whatever their own particular input may be, and so such an ‘I don’t give a damn!” attitude instead leads them to pursue whatever other more personal interests in life.

One could further argue that were such political non-involvement by the citizenry on the North Shore to continue as a trend, future elected governments will become less and less democratic and deteriorate even further in the direction of what could be deemed: dynastic politics; autocratic leadership; a dangerous centralization of decision-making powers, and; the manufactured consent of the populace by those always few preferred ones, motivated by the same mindset, who always ‘get the nod’. In such a closed, alienating system the citizenry can only but feel even more so like mere subordinates and rubber stamps rather than equals.

Historically, a weak democratic process on the North Shore has allowed voters, albeit however pathetically small in actual numbers, to decide upon who is to lead their governments and continually tip the balance of power in favour of one model or another of out-of-control growth, with the results of federal and provincial elections not much better.

When, indeed, things today might be considerably different if some kind of compulsory voting or proportional representation system had previously already been in place, where a truly representative majority of those registered to vote indeed were called upon, as is required in such voting systems, whether enforced or not enforced, in federal, state and municipal governments, worldwide, such as in Australia and 28 other countries like: Belgium, Argentina, Ecuador, Liechtenstein, Costa Rica, Paraguay, Mexico, Panama, Luxembourg, Turkey, Mexico, Libya, Lebanon, Bolivia, Bulgaria, Peru, Singapore, Gabon, Guatemala, Honduras, Egypt, Greece, Paraguay, Dominican Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Schaffhasen canton of Switzerland, North Korea and Nauru.

Without such a similar voting system in place on the North Shore, throughout British Columbia and indeed Canada at large the realities of daily life will remain markedly unchanged and continue as they are. Under such conditions, one could argue that a populace so poorly represented seldom gets what they need but always gets what they deserve.

On the other hand, a compuslory voting system is based more upon the belief that it’s the responsibility and duty of every citizen, rather than a right, to cast their vote for whatever government they so choose to represent them. Some such systems even impose a financial penalty, of up to $170.00, on those citizens who fail to fulfill their civic duty. In practice, the results of such a compulsory voting system gives more political legitimacy, based upon a higher voter turn out, and a more genuine mandate to whoever is elected to govern which, in turn, benefits all individuals concerned. Other advantages to compulsory voting are that it: stimulates a broader interest in politics; acts as a sort of civic education; provides the stimulus for more political awareness which leads to a better informed population; improves the caliber of those who choose to run for office, as well as; the quality of the decisions they make.

Without such a system in place on the North Shore basically the same results probably will continue to occur with every future election. For instance, during the last voting cycle in 2014 in the District of North Vancouver the top elected councillor who currently holds office only received 11% out of the niggardly 23% of those registered who actually voted, while the lowest legally-elected standing councillor received only 8% of the tallied votes. Whereas in West Vancouver District and the City of North Vancouver, respectfully, a mere 28% and 30% of the registered voters elected into office those who have since been able to exercise enormous power regarding incredibly critical issues, such as: population densities, types of housing, size of commercial and residential high-rise development, building variances, expanded infrastrucure and complex traffic strategies that now are impacting upon the North Shore’s entire future course and direction, if not totally redefining whatever might one day be called its new ‘iconic look’, that will certainly be a radical departure from the original that once made the North Shore such an especially unique place. In previous election cycles in 2008 and 2011 the actual abysmal percentages of voter participation were so low as to cause some observers to perceive it as a veritable insult to the very democratic principle of free and open elections.

The problem with so little voter participation begins with the narrow, stacked way that potential new candidates for public office traditionally are vetted in the so-called ‘All-Candidate Meetings’ that occur on the North Shore during every electoral process; coupled with a lack of adequate coverage by the press that barely puts elections on the radar and gives them little of the special attention they deserve; neither of which seldom provide open and fair hearings of new candidates; especially when they hold progressive, or even radical philosophies, who would dare to try to break into and change the current tightly-controlled political system. Narrow, pre-selected questions chosen by those who organize and conduct the All-Candidate Meetings severly limit spontaneity and extemporaneous questions and comments by either the candidates themselves or attending general public; to the point that some deem the effort woefully lacking in incisiveness at ever getting at and exposing the real differences that exist between the incumbent politicians running for re-election and the fresh ideas being offered by those new challengers attempting to break through all the political bias and inertia.

For those among the citizenry who really do care, it behooves them in the coming weeks and months leading up to the 2018 election to contact their local community association (www.dnv.org/our-government/election-information-voters), to find out who is sponsoring their all-candidate meetings and demand a more astute process of candid, lively, open debate between the candidates and citizenry.

Another inherent problem on the North Shore is the way its political process tends to turn away or ‘turn off’ various segments of the voting public from actively participating and engaging in a process that has become too autocratic. Many among the North Shore’s citizenry know exactly what it means and feels like to have ever been treated by the politicians and their developer allies as if they were simply typecast as another one of ‘those pesky locals’, whose concerns and viewpoints, however dissident or unpopular, about whatever given controversial problem, issue or development plan, typically end up being superficially appeased, ignored, paid little more than lip service and then summarily dismissed. Hence, in many instances real, lasting bonds of trust seldom ever exist or are maintained between the politicians, their staffs and many of the citizenry. It always seems more like a relationship between the politico’s ‘up there’ in their ‘lofty crystal palaces’, and the citizenry somewhere ‘down there’ in their ‘burrows and warrens’.

One example of such a lack of trust is the cynical way in which many among the general public perceive the same old political game that is played time and again over whatever new proposed high-rise, high-density development plan. Whenever the community is invited to attend a so-called ‘Open House’ or ‘Public Hearing’ about whatever the proposal, the ‘dance’ is always the same. A pathetic few diehard residents attend, with the plan invariably receiving final approval in spite of whatever negative, critical input happen to be given by those few in attendance. Many savvy citizen-voters often don’t even choose to attend because they know or at least perceive whatever proposal put forth is already a virtual ‘shoe-in’ anyway because it has long since been hatched and ‘cooked’ elsewhere in closed-door settings between the principal politicians and developers involved before ever reaching the public’s attention. By the time the so-called ‘public hearing’ process is held the perception is that it’s simply one of the obligatory rituals always held to give formal semblance to the plan having been ‘democratically’ arrived at, with a modicum of duly acknowledged input by the public before finally receiving the necessary ‘rubber stamp’ approval.

Democracies place great emphasis on the rights of the individual but less so on an individual’s responsibilities to society. It’s easy to give short shrift to the civic responsibility of voting and instead opt for solely devoting one’s whole time with friends and family, or the decadence of some eat-drink-and-be-merry lifestyle but such choices seldom contribute to the welfare and future of the community or society at large and only exacerbate things as they are.

So with these thoughts in mind one can only hope, in the absence of any compulsory voting or proportional representation system in place, that, miraculously, a surprising difference will occur in the results of the upcoming 2018 election cycle on the North Shore of Canada.

Jerome Irwin is a freelance writer, author,long-time activist and political organizer among his community of Lower Capilano, on the North Shores of Vancouver, British Columbia.