The depth of our dilemma is suggested by a remarkable essaypublished in New York magazine by David Wallace-Wells, “The Uninhabitable Earth,” which upset a lot of climate scientists and some activists by laying out some of the worst-case future scenarios that climate science forecasts unless our activism is visionary enough to bring about some of the better ones. The hard truth seemed to upset quite a few people who have been trying to wake up the public to the climate crisis because the experts held that telling the truth was just too much for people to live with.

No single thing, and quite possibly nothing at all, can get us out of the epic mess we’ve made this time. Let’s stipulate that at the outset. It’s pretty obvious that situations like “the Anthropocene” and “climate crisis” are here to stay.

Yet try we must, and try we do. Let’s stipulate that too, at least for some of us.

All this being the case, well, then what? Then what?

There can be no definitive answers to such questions. So if you possess that kind of hope, then you can stop reading now.

But if you’re still with me, let’s explore how hope works.

A few thoughts on the kinds of hope we probably don’t need

In an essay called “Beyond Hope,” the inimitable Derrick Jensen begins by noting “THE MOST COMMON WORDS I hear spoken by any environmentalists anywhere are, We’re fucked.” Jensen tells us “Frankly, I don’t have much hope. But I think that’s a good thing. Hope is what keeps us chained to the system, the conglomerate of people and ideas and ideals that is causing the destruction of the Earth.” He develops his critique of hope by asking:

Does anyone really believe that Weyerhaeuser is going to stop deforesting because we ask nicely? Does anyone really believe that Monsanto will stop Monsantoing because we ask nicely? If only we get a Democrat in the White House, things will be okay. If only we pass this or that piece of legislation, things will be okay. If only we defeat this or that piece of legislation, things will be okay. Nonsense. Things will not be okay. They are already not okay, and they’re getting worse. Rapidly….

He then seals the case with this claim:

Hope is, in fact, a curse, a bane. I say this not only because of the lovely Buddhist saying “Hope and fear chase each other’s tails,” not only because hope leads us away from the present, away from who and where we are right now and toward some imaginary future state. I say this because of what hope is.

More or less all of us yammer on more or less endlessly about hope. You wouldn’t believe — or maybe you would — how many magazine editors have asked me to write about the apocalypse, then enjoined me to leave readers with a sense of hope. But what, precisely, is hope? At a talk I gave last spring, someone asked me to define it. I turned the question back on the audience, and here’s the definition we all came up with: hope is a longing for a future condition over which you have no agency; it means you are essentially powerless….

When we stop hoping for external assistance, when we stop hoping that the awful situation we’re in will somehow resolve itself, when we stop hoping the situation will somehow not get worse, then we are finally free — truly free — to honestly start working to resolve it. I would say that when hope dies, action begins.

Philosopher and activist Terry Patten, author of A New Republic of the Heart: An Ethos for Revolutionaries (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2018) has a nice response to doomists and catastrophists: “If ‘it’s too late,’ we can at least write a beautiful end to the human story, through self-understanding, love-in-action, brother-sisterhood, elegance, genius, and wisdom. That is why it’s so crucial, regardless of ultimate outcome, that we cultivate our best capacities and form intimate spiritual friendships that can grow into a broader social movement inspired by a grounded, healthy, and responsive spiritual vision.”

Hope that Works

This sounds like a promising kind of hope, doesn’t it? It’s the name of a class I was invited to co-teach at UC Santa Barbara in the spring of 2018 (and in fact, this essay started life as my last words to the class). Proposed by environmental lawyer, scholar-activist, and eco-warrior Marc McGinnis in the spring of 2017 as an antidote to the shared overwhelming despair he felt after our disastrous 2016 election, the course engages students in environmental studies at UCSB in two major ways: by inviting in a variety of teachers, students, and activists to discuss what hope that works might mean, and by discussing the ideas in Active Hope, a book by Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone.

Practical hope, then, it was suggested by many of the activists who spoke to us, is generated on the ground of collective action in the present and by the creation of inspiring visions of the future. I think of Paul Hawkens’s tremendous group project, Drawdown, promising “the most comprehensive plan ever to reverse global warming,” and presenting one hundred solutions. Yes, it is limited when it comes to how we are to achieve most of these 100 best ideas on emissions reductions, but it makes the point that there are dozens and dozens of possibilities within reach, if only we summon the courage to fight for them.

Or take the budding European movement for Degrowth, which calls on the wealthy consumers of the global north to cut back their own earth-destroying pursuit of happiness through the acquisition of material objects or fossil-fueled experiences (and think of the further resources we can save by spending less on the military, financial services, insurance, mindless advertising, high-end medical technologies, crappy food, and disposable gadgets [see Giorgos Kallis, In Defense of Degrowth: Opinions and Manifestos (Creative Commons, March 2017) and the 2015 Federico Demaria et al. collection, Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era].

Or consider buen vivir, from the Quechua words sumak kawsay, rendered ungracefully into English as “living well” (as opposed to the affluenza-drenched U.S. middle-class idea of living the “good life”), one of the alternatives that comes from the global south, which teaches us that a satisfying life can be built on cultivating relationships of real solidarity in our communities (see Pablo Solón, “Is Vivir Bien possible? Candid Thoughts about Systemic Alternatives” (August 2016). The Transition Town movement teaches the same lesson, as does the Eco Vista project closer to our home in Santa Barbara. Many of these new ideas are laid out in Arturo Escobar’s stunning new book-length meditation Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds (Durham: Duke University Press. 2018).

The varieties of hope that works, then, are limited only by our imaginations and our desires for change. They are everywhere.

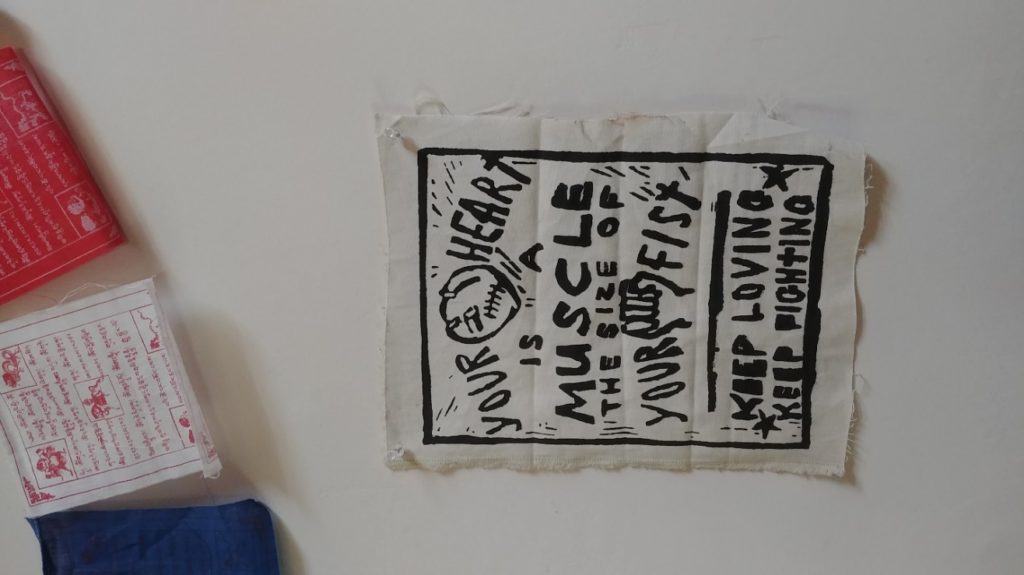

Sidewalk in the Mission, San Francisco. Photo: Joe Ashenbrucker

Active Hope

The subtitle of the book assigned for our class is How to Face the Mess We’re in Without Going Crazy. This signals its starting point…

One of the big takeaways from the book for me was to reaffirm the centrality of spirituality in activism, whether this derives as it does for the authors from Buddhist sources, or for others whom I know from a reverence for the Earth/Creation/Gaia/Pachamama (all these sources of wisdom speak to me).

By great coincidence, as I was working on this essay Joanna Macy gave a two-hour webinar on the first half of the book. She said many profound things, including:

“If you don’t speak up, or ask questions, nothing changes” (this in connection with the legend of Parsifal and the Fisher King).

“The crisis is not going to be resolved by me, or you, or any one of us, but rather all of us, if we can listen well enough to open up channels to share what is within us.”

“It’s not our power, our smarts, our busy-ness, it’s letting ourselves be used as conduits for whatever it is we are serving” [reminding me of the streets of Paris in 2015, where the slogan of the climate justice movement at COP 21 was “We are Nature defending herself.”]

Source: John Jordan

Source: John Jordan

Joanna noted that “In jazz, when you are playing, you listen to the whole group, but also to what you yourself can offer into the situation. We are servants to larger systems than ourselves, to a larger intelligence…”

She relayed Thich Nhat Hanh’s answer to the question, “What’s the most important thing we can do right now?” His reply: “Hear within yourself the sound of the Earth crying…”

She closed with a recounting of the twelfth-century Tibetan Shambhala Prophecy, which I paraphrase here from my notes on her words as the prophecy was related by her teacher:

There comes a time when all life on Earth is in danger. Barbarous powers arrive with powerful weapons and dangerous technologies. When the life of all beings seems to hang by a frail thread, this is the time of the Shambhala Warrior. You can’t tell who they are just by looking at them. They have no home. Great courage – moral and physical – is required of them now as they are going into the heart of the barbarians, their corridors of power, to dismantle their weapons.

Anything made by the human mind can be unmade by the human mind. The problems we face today arise from our habits of mind, our fears (including our fear of facing our fears). Now the Shambhala Warriors go into training, to learn to use two weapons – one is compassion, and the other is insight into the radical interdependence of all phenomena.

Neither is enough by itself. Do not be afraid of the suffering of your world…. This is not a war of good guys and bad guys. The line between good and evil runs through every heart. Our smallest actions ripple through the whole web of life. [We need both the] heat of compassion and cool understanding of the web of existence.

If my teacher had told me how this whole situation is going to turn out, I wouldn’t have believed the story. It’s that uncertainty that keeps you alive.

The spiritual (not necessarily religious, but certainly philosophical and existential) side of activism plays a surprisingly large role in the hopeful activism that I see taking shape in the world, as evidenced in the pages of Wen Stephenson’s excellent What We Are Fighting For Now is Each Other: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Climate Justice, or Pope Francis’s trenchant encyclical from 2015, Laudato Si’, or the Dalai Lama’s eloquent statement at COP 15 in Hopenhagen (or was it Nopenhagen?). It can be detected even in the more despairing note sounded by Paul Kingsnorth’s Dark Mountain Project and its haunting Manifesto. And indeed Wen and Paul engaged in a vigorous debate in which Kingsnorth said, a bit like Derrick Jensen:

Whenever I hear the word “hope” these days, I reach for my whisky bottle. It seems to me to be such a futile thing. What does it mean? What are we hoping for? And why are we reduced to something so desperate? Surely we only hope when we are powerless?

This may sound a strange thing to say, but one of the great achievements for me of the Dark Mountain Project has been to give people permission to give up hope. What I mean by that is that we help people get beyond the desperate desire to do something as impossible as “save the Earth”, or themselves, and start talking about where we actually are, what is actually possible and where we are actually coming from….

I don’t think we need hope. I think we need imagination. We need to imagine a future which can’t be planned for and can’t be controlled…. Giving up hope, to me, means giving up the illusion of control and accepting that the future is going to be improvised, messy, difficult….

I feel I have to respond to all of this by giving up hope, so that I can instead find some measure of reality. So I’ve let hope fall away from me, and wishful thinking too, and I feel much lighter. I feel now as if I am able to look more honestly at the way the world is, and what I can do with what I have to give, in the time I have left. I don’t think you can plan for the future until you have really let go of the past.

To which Wen’s rejoinder runs:

There’s something almost hopeful about that last page of the manifesto, and the last lines: “Climbing Dark Mountain cannot be a solitary exercise…. Come. Join us. We leave at dawn.”

But it occurs to me that “beauty” and “truth” (like politics) are human “confections” – anthropocentric categories. And this seems to imply a belief that something like civilization, which gave birth to art and philosophy, will not only survive, but is worth fighting to preserve. And yet, how does one propose to preserve beauty and truth, these human constructs, unless the climate is stabilized? And how does one propose to do that without engaging in politics? Are you suggesting that a new art and philosophy will give rise to a new politics? Maybe it will. But do we really have time to wait for that?

It is at this point that I part ways with both Wen and Paul, because it seems to me that the two – storytelling and politics – are intimately connected, and bound together by hope of the most active variety. My bet is that we cannot change our politics, and therefore transform the world in the directions we’d like to see, unless we find the stories that will sustain us and draw others into the struggle for climate justice. I have a whole theory of how radical social change occurs, that emphasizes that we make change by shaping political cultures of both opposition and creation that make the connections between our lives, our planetary crises, and our futures clear and important to ourselves, on a visceral and emotional level as much as a political and strategic one. Hope’s dwelling place must be at that most visceral and emotional levels of our being.

Critical Hope

What is critical hope? I’m not sure I know how to distinguish it from the last kind of hope I have to offer, which is “radical” hope. But my colleague and friend, Sarah Ray, who also spoke in the class (see a version of the talk she gave here) clued me in to Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade’s piece “Note to Educators: Hope Required When Growing Roses in Concrete,” written in 2009.

He opens with a quote from the radical popular Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of Hope (New York: Continuum, 1997):

The idea that hope alone will transform the world, and action undertaken in that kind of naïveté, is an excellent route to hopelessness, pessimism, and fatalism. But the attempt to do without hope, in the struggle to improve the world, as if that struggle could be reduced to calculated acts alone, or a purely scientific approach, is a frivolous illusion.

Duncan-Andrade has much to say on the topic, and it is not unimportant that he was writing at the dawn of Barack Obama’s first term in office, who was propelled to the presidency after writing a book called The Audacity of Hope, and campaigning on a single word:

Image by Jason Taellious (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Duncan-Andrade’s world is that of teaching in the inner city schools of Oakland, where hope is raised by well-meaning liberal educators on a daily basis, but where hope is deferred and ultimately dies unless and until it is matched by compassionate giving of oneself. This is a remarkable story which has led to the creation of an alternative school, the Roses in Concrete Community School.

Duncan-Andrade understands “critical hope,” then, as the enemy of hopelessness, the antidote to cheap hope, false hope, mythical hope, hokey hope. The title of the essay (and my own in this piece is a variant on it) is drawn from Tupac Shakur, who in his poem The rose that grew from concrete “referred to young people who emerge in defiance of socially toxic environments as the ‘roses that grow from concrete.”

The constituent parts of critical hope, Duncan-Andrade believes, are found in material hope, which refers to the resources needed to make the world we want, and in Socratic hope – “the understanding of both Socrates’ statement that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’ and Malcolm X’s extension that the ‘examined life is painful’.” With Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone, Duncan-Andrade affirms that “Socratic hope requires both teachers and students to painfully examine our lives and actions within an unjust society and to share the sensibility that pain may pave the path to justice. In my research, effective educators teach Socratic hope by treating the righteous indignation in young people as a strength rather than something deserving of punishment.”

The final ingredient of critical hope is audacious hope. Writing for educators, Duncan-Andrade says in words that summon us to scholar-activism:

To provide the “authentic care” that students require from us as a precondition for learning from us, we must connect our indignation over all forms of oppression with an audacious hope that we can act to change them. Hokey hope would have us believe this change will not cost us anything. This kind of false hope is mendacious; it never acknowledges pain. Audacious hope stares down the painful path; and despite the overwhelming odds against us making it down that path to change, we make the journey again and again. There is no other choice. Acceptance of this fact allows us to find the courage and the commitment to cajole our students to join us on that journey. This makes us better people as it makes us better teachers, and it models for our students that the painful path is the hopeful path.

Radical Hope

For me, the global climate justice movement is a source of radical hope and runs on radical hope. So does the Transition Towns movement, and so many other communities that are making the transformations we need happen by showing us how to stretch the limits of the possible.

Likewise the newest idea I am playing with and trying to take up: an invitation to re-imagine together some new kind of party. We have to allow ourselves to think about the impossible – a future without obscene inequality, without irrelevant political leadership, without cultures of violence, and indeed, without climate catastrophe, or at least, the least amount of it we can accomplish.

A special guide to this kind of future is the ever-growing genre of cli-fi, and within it the current that is becoming known as Solar Punk, which replaces the dystopian themes of Hollywood with more realistic and at the same more life-affirming stories of the future. One can also consult the works of Kim Stanley Robinson, who back in the 1990s presented three versions of California’s future – the post-apocalyptic The Wild Shore, the depressingly business-as-usual Gold Coast, and finally, the more hopeful, yet still realistic Pacific Edge – underlining that the choices we make will partly determine which future we get. Or Octavia Butler’s post-collapse Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, which point toward the emergence of whole new spiritualities with the coming of the Anthropocene. Or start with a great new collection of short stories, Everything Change: An Anthology of Climate Fiction brought to us by Arizona State University’s Center for Science and the Imagination (perhaps we need a sisterly counterpart – the Institute for Hope and Creativity!).

Fiction frees us to imagine how other worlds may come about, in a future diminished by the wreckage of our own (un)civilizational path, to be sure, but holding out the radical hope of the just social transformations that have eluded us so far.

As for me, hope has a place among the tight circle of key words I carry around. Words like imagination, creativity, love. They stand in some kind of relationship with each other, not as distant or solitary beacons in the night, but rather more like an affinity group I live for and with. They are what I wake up to in the morning, keep by my side during the day, and dream with at night. In the spaciousness of the universe and the vastness of deep time, we amount to very little. But we are right here, right now, and we offer ourselves to this struggle, with countless other beings, in every corner of the planet.

Let’s find each other.

John Foran is professor of sociology and environmental studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is a co-founder of the Climate Justice Project [www.climatejusticeproject.org] and of the International Institute of Climate Action and Theory [www.iicat.org]. He is the author of Fragile Resistance: Social Transformation in Iran from 1500 to the Revolution (1993) and Taking Power: On the Origins of Third World Revolutions (2005). A member of System Change Not Climate Change, the Green Party of California, and 350.org, he now studies movements for radical social change in the 21st century, with special focus on the global climate justice movement.

Originally published by Resilience.org