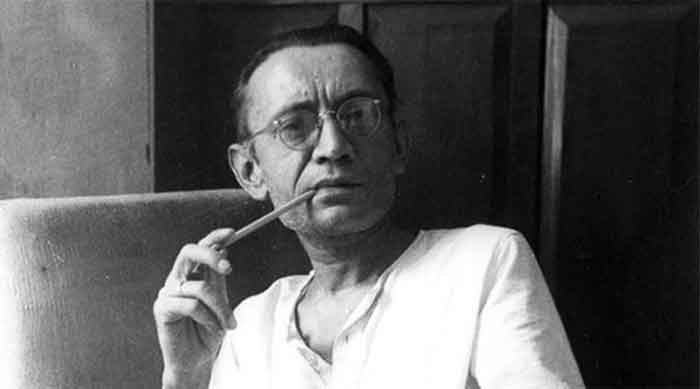

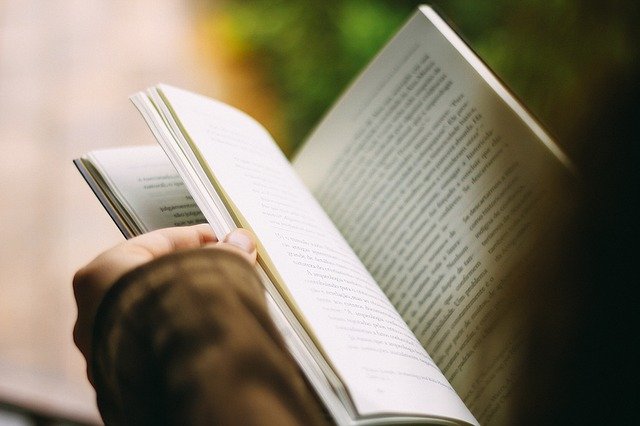

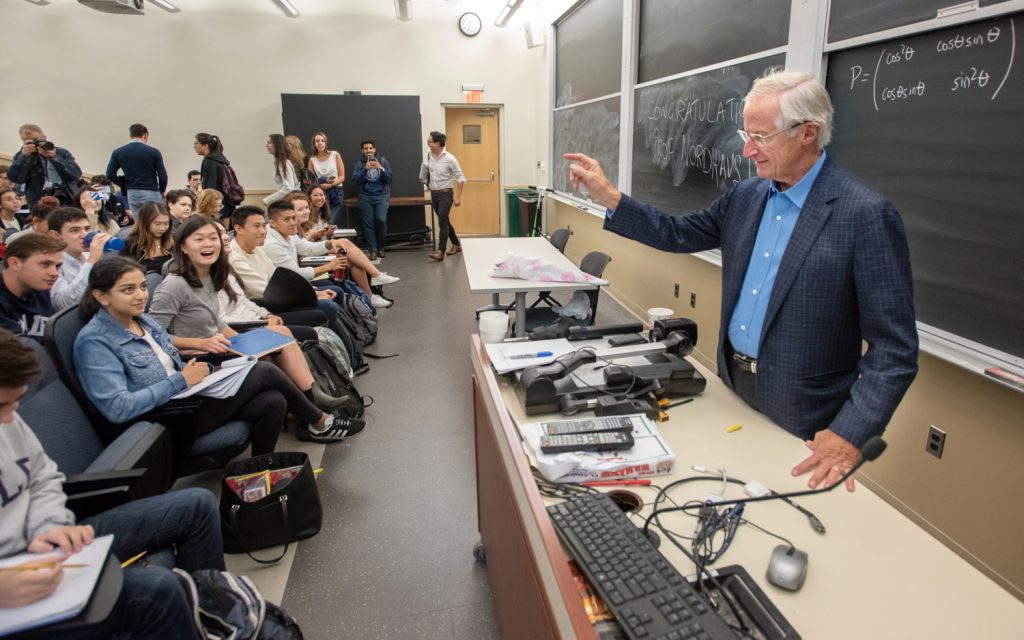

William Nordhaus shaping vulnerable minds in his Yale classroom – Oct. 8, 2018. (Photo credit: Yale/ ©Mara Lavitt)

How ironic for the Washington Post to opine “Earth may have no tomorrow” and, two pages later, offer up the mini-bios of William Nordhaus and Paul Romer, described as Nobel Prize winners.

Without more rigorous news coverage, few indeed will know that Nordhaus and Romer are epitomes of neoclassical economics, that 20th century occupation isolated from the realities of natural science. Nordhaus and Romer may deserve their prizes for economic modeling, but each gets an F in advanced sustainability.

Nordhaus won his prize (actually the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel”— not the Nobel Prize per se) for his mastery of mathematical modeling. He applied his skills to carbon taxes for lowering greenhouse gas emissions. All along he prescribed economic growth – the key driver in greenhouse gas emissions—as the way to afford such taxes!

In 1991 Nordhaus uttered one of the most iconic sentences in the history of unsustainability: “Agriculture, the part of the economy that is sensitive to climate change, accounts for just 3% of national output. That means that there is no way to get a very large effect on the US economy” (Science, September 14, 1991, p. 1206). Think about that. He must have set a graveyard’s worth of classical economists (Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill…) to rolling. They’d be rolling in laughter if the folly of Nordhaus wasn’t so dangerous.

No follow-up should be needed to expose the ludicrous nature of Nordhaus’s statement, but just in case: Agriculture is the very foundation of the economy. No agriculture, no anything else. Think about it. Any hit on agriculture—whether from climate change, bad luck, or stupid policies—has a magnified effect on the entire, integrated economy. Nordhaus’s “3%” statement was a classic case of ivory-tower cluelessness.

Too many trees for seeing the forest?

Romer, meanwhile, deserves some credit for his elegant theory of “endogenous technological change,” which took the work of Robert Solow (the father of economic growth theory) to the next level by describing in nuanced detail how R&D leads to technological progress. That said, there has never been a bigger forest missed for so many trees. For him, all that mattered was capital and labor; he said nothing about land, natural resources, or the environment.

Some readers may recall Julian Simon, the ultimate Pollyanna who claimed in the 1980s (and I paraphrase after thoroughly reviewing his 813 page Ultimate Resource II during my post-doc studies), “Sure, there are environmental problems caused by growth, but the more people we have, the more brains we have to solve the problems. Therefore, the more people we have the better, without limit forever.” Romer’s work amounted to a highly nuanced repetition of Simon’s self-christened “grand theory.”

Romer said in a nutshell: We have capital and labor. Part of the labor force is devoted to research and development (R&D). As limits arise, we get over them with more R&D. So we need ever more people, with ever more devoted to R&D, to keep raising the bar for GDP.

For Romer, it was as if ideas alone could overcome water shortages, biodiversity loss, mineral depletion, soil erosion, pollution, and climate change. As if ideas could be perpetually borne out of human minds struggling in a degrading environment, a warming climate, and an imperiled agricultural base (not to mention a crowded, noisy, and stressed out society). Romer was like a cook thinking up recipes with no idea where the ingredients would come from.

A generation and then some of economists and business students have been led to the exceedingly dangerous myth that there is no limit to either population or economic growth. Nordhaus and Romer have done as much as anyone to lead them into such a fallacy. Yet politicians and publics heed their advice, while the media regurgitates their fallacious notions.

Does Earth have “no tomorrow,” as the Washington Post wondered? One thing is for sure: Any hope for a happy tomorrow on Earth means rejecting the neoclassical economics of today. Even when such economics wins the “Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.”

Dr. Brian Czech is an author, teacher, full-time conservation biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and a recognized authority on Ecological Economics. Described by Publisher’s Weekly as “as good at popularizing economics as Carl Sagan was science,” Dr. Czech argues that mainstream economics is based on a dangerously flawed theory of economic growth, which can be dismantled through ecological principles. His first book Shoveling Fuel for a Runaway Train has become a popular manifesto for Ecological Economists as a roadmap to a sustainable future, and he has also produced a video, The Steady State Revolution: Uniting Scientists and Citizens for a Sustainable Society.