On his 90th birthday, a tribute to the man whose life more than anyone else’s tells us what it takes to be human

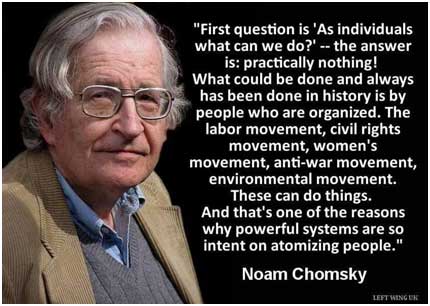

Six weeks after 9/11, Noam Chomsky was on a brief lecture-tour in India when one of his engagements took him to the Asian College of Journalism in Chennai. There, in the Q&A after his talk, a budding journalist asked him if Chomsky was not being “too optimistic” about the possibility of change in a world that otherwise looked quite bleak. The Professor’s reply was simple, matter-of-fact:

…there is no measure of how optimistic you ought to be. In fact, as far as optimism is concerned, you basically have two choices. You can say, ‘Nothing is going to work and so I am not going to do anything’. You can therefore guarantee that the worst possible outcome will come about. Or, you can take the other option and say, ‘Maybe something will work and I will engage myself in trying to make it work. Maybe there is a chance that things will get better.’ That is your choice. Nobody can tell you how right it is to be optimistic……

No hint of high passion here, nor any rhetorical flourish, for Chomsky clearly thinks that he was merely stating the obvious. But he also knows that, for the modern-day intellectual, often there is no such thing as the obvious. As far back as June, 1966, while delivering at Harvard (in an anti-Vietnam War rally) what proved to be one of the 20th century’s great speeches, he had said:

It is the responsibility of intellectuals to speak the truth and to expose lies. This, at least, may seem enough of a truism to pass without comment. Not so, however. For the modern intellectual, it is not at all obvious.

For Noam Chomsky, however, this responsibility was always axiomatic. His life was early anchored in this responsibility, and that tie has held firm and true ever since the late 1930s, when, as an adolescent, his moral consciousness was being shaped by events such as the Spanish Civil War, the rise and the crimes of Nazism and the West’s (at least partial) complicity in those crimes, Stalin’s purges and the horrors of the Second World War. At age 10, he wrote his first ‘political’ essay for his school magazine – a piece on Red Barcelona that fell to Franco’s Falangists that year (1938). By 1960, he was a strident critic of American foreign policy in the Cold War era, repeatedly tearing the veil off the facade of ‘American altruism and humanitarianism’ in external affairs. In The Responsibility of Intellectuals, the landmark 1967 essay that had evolved out of the Harvard anti-war speech, he squarely confronted American intellectuals (and Americans in general) with the question of war guilt: in the context of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and, more immediately, of America’s war on Vietnam:

Let me … return to .. the responsibility of intellectuals. (Dwight) Macdonald (American activist-writer) quotes an interview with a death-camp paymaster who bursts into tears when told that the Russians would hang him: “Why should they? What have I done?”, he asked. Macdonald concludes: “Only those who are willing to resist authority themselves when it conflicts too intolerably with their personal moral code, only they have the right to condemn the death-camp paymaster.” The question “What have I done?” is one that we may well ask ourselves, as we read, each day, of fresh atrocities in Vietnam – as we create, or mouth, or tolerate the deceptions that will be used to justify the next ‘defence of freedom’.

Chomsky’s personal moral code never left any room for ambivalence. His choice, as he indicated to the young Chennai journalist, was made early on in his life: he forever asks himself the question “What can I do?”, for he knows that, only then, can one spare oneself that agonizing, wrenching question later: “What have I done as this situation was developing around me?” During 1966-68, safely settled at the pinnacle of a brilliant professional career as one of the world’s foremost language theorists/philosophers, he yet plunged headlong in the anti-war movement then sweeping through America’s cities, her university campuses, participating in teach-ins, protest marches and in that electrifying sit-in demonstration just outside the Pentagon which resulted in one of his several jail-terms. The novelist Norman Mailer, who happened to be Chomsky’s cellmate in prison and was meeting the young professor for the first time, describes Chomsky as “a slim, sharp-featured man with an ascetic expression and an air of gentle, but absolute moral authority”. He also recalls how Chomsky seemed “uneasy at the thought of missing class on Monday”. Chomsky, then 37, taught at MIT, where he had been made a tenured full professor at age 32 in the School of Modern Languages and Linguistics. His sharp and unremitting critique of America’s war on Vietnam made him virtually persona non grata in the US, denying him any space in either the liberal or the conservative media universe, and threatening the funding of the many research programmes he ran at the MIT. In the end, it could only have been his formidable academic credentials –and his standing as an internationally acclaimed expert – that saved his job.

A precocious child and a brilliant student, Avram Noam Chomsky received his PH D from Penn at age 26, but had been a Harvard Fellow before that and was a well-known name among linguists and language philosophers already. He soon emerged as one of the pioneers of the Cognitivist (as opposed to the Behaviourist) framework for linguistics. Syntactic Structures, his first book published when he had just turned 28, had revolutionised linguistic theory. He followed it up with a steady stream of sparklingly original books and treatises such as Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, The Sound Patterns of English, Topics in the Theory of Generative Grammar and Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Rationalist Thought. By the mid-1960s, Chomsky was already among the foremost language theorists/philosophers in the world. His Language and Mind (1968) is credited with opening the door to psycholinguistics and neurolingusitics. His academic influence soon extended to such widely diverse fields as psychology, anthropology, computer science, neuroscience, education theory, mathematics and literary criticism, besides, of course, philosophy. No wonder, then, that he remains the most-cited scholar in all academic work in the humanities and social sciences put together. The number of books Chomsky has himself authored (well over 100, not counting the many, many others which he has collaborated on or edited or which comprise interviews given by him) easily makes him one of the most prolific writers in human history. As he turns ninety, he remains as productive as ever, having published at least 7 books over the past 3 years.

A vast majority of Chomsky’s books and other writings, though, cover non-academic, political subjects. Titles such American Power and the New Mandarins; Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass media; Necessary Illusions; Pirates and Emperors: International Terrorism and the Real World; World Orders, Old and New; Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance; 9-11; Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship; and the more recent Requiem for the American Dream and Optimism over Despair: On Capitalism, Empire and Social Change, all best-sellers, bear testimony to Chomsky’s unrelenting search for the truth, behind carefully-crafted appearances, in American foreign policy and in the country’s media culture. His staggeringly wide scholarship, eerily keen eye for detail and phenomenal memory combine in his fluent, lucid, often acerbic, prose to make him modern-day-world’s most famous, and eminently readable, polemicist. He has long been a thorn in the side of successive US administrations, Republican and Democratic, for his incisive, insistent probing of the real drivers of American policy in Central and South America, Indo-China and the Middle East. His unblinking, unforgiving gaze on how the US propped up the most brutal regimes in countries like Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala and Chile through the 1970s-1980s, earned him a place on President Nixon’s (in)famous ‘Enemies List’, which became public through a faux pas of a Nixon administration functionary in course of the Senate Watergate hearings. For a long time, his was the lone Western intellectual voice against Indonesia’s unspeakable atrocities in East Timor. Agio Pereira, one of the front-ranking leaders of the Maubere Resistance in East Timor, fondly remembers how he first “heard of Prof Chomsky… in the late 1970s when … he paid from his own pocket for some Timorese refugees to fly to the USA to speak out about the tragedy of the people of East Timor”. Chomsky championed the cause of East Timor’s independence at numerous international forums (including the UN), lecturing, meeting activists and writing about it tirelessly till the nation won its freedom in 2002. In February, 2002, he appeared unsolicited in an Istanbul court to plead that he be made a co-accused in a prosecution involving Fatih Tas, an important Turkish publisher. Tas had published a Turkish translation of Chomsky’s American Interventionism, a book of essays highlighting the Turkish government’s relentless persecution of the Kurdish population which amounted, in Chomsky’s words, to “one of the most severe human rights atrocities of the 1990s”. Not amused, the Turkish state was prosecuting the publisher for “producing propaganda against the unity of the country”. To the government’s dismay, however, Chomsky himself turned up in Turkey to ask that he be tried alongside Tas. The professor’s presence in Istanbul made sure that all the world’s media were also present in strength in the court on the fateful day. The Turkish authorities baulked at the idea that their record of violence against the Kurds could possibly be brought out in graphic detail in the courtroom even as the whole world looked on, real-time. They panicked, and dropped the prosecution, saving Tas from a possible jail sentence of at least a year. Chomsky’s reaction was characteristically under-stated. Because “the United States provides 80% of the arms for Turkey for the express purpose of carrying out repression”, he felt it was his duty, as a US citizen, to protest against Turkey’s human rights abuses. What must also have played on his mind – though he wouldn’t think of mentioning it – is that it was his book that had got the publisher into trouble.

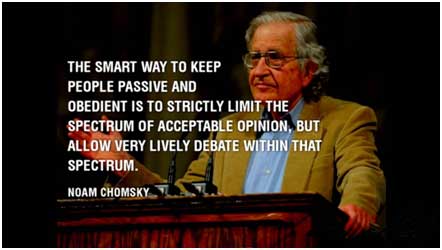

One theme that Noam Chomsky has indefatigably worked on over many decades, is that of the freedom of expression in liberal democracies. He believes that this much-vaunted freedom is largely a sham, because powerful interest groups, solidly invested in maintaining and strengthening the status quo in the political economy of ‘advanced’ democracies, manage to limit the spectrum of public discourse with finesse. Once the contours of debates have been firmly, unalterably drawn – and any outliers irrevocably ‘demonstrated’ to be deviant or anomalous— public opinion is conditioned to stay within those clearly-marked boundaries only, and not stray beyond them. Chomsky famously described this process as ‘the manufacturing of consent’, and he has demonstrated the efficacy of this system in the context of the American liberal media/ liberal opinion time and again. He showed how, when opposition to America’s involvement in Vietnam was growing within the US, the media helped the regime in successfully turning the debate into one revolving around questions of expediency rather than of right or wrong. American Power and the New Mandarins cites numerous instances of ‘soul-searching’ liberals arguing that stepping up military commitment to Vietnam did not make sense because it was proving to be not so productive/cost-efficient. This tendency met with the media’s broad support and encouragement, because it did not raise – on the contrary, it undermined – the really important issue at stake here – the fundamental immorality of the intervention – which the mass protests called into question.

Born to Jewish parents himself, Chomsky has been one of the sternest critics of Israel’s illegal occupation of Arab territories and of its abysmal human rights record, once characterising Israeli action in Gaza as “worse than (the South African) apartheid”. Hardly surprising, then, that he was barred from entering Israel, on a lecture tour, in 2010. In 2011, he lent his powerful voice to the Occupy movement in the US, lecturing and writing about the initiative repeatedly, his speeches, articles and interviews later being collated in a book titled Occupy. In February, 2016, when the government of India was seeking to foist a fraudulent, though impossibly clumsy, case of sedition upon the students of JNU in Delhi, Chomsky added his name to an angry denunciation of the government’s action. In October this year, he travelled to Brazil to agitate against the likely (then — a fact now) election of “the fascist, racist, misogynist and homophobic candidate (Bolsonaro) who calls for violence and armed repression”. Indeed, despite the Brazilian authorities’ reluctance to let him meet the Workers’ Party leader Lula da Silva, he insisted on interviewing Lula in his prison cell. And only last week, he told an interviewer that he thought Donald Trump and his Republican cohorts were ‘criminally insane’. He was, in fact, only elaborating on a point he had made sometime back: that the Republican Party was “the most dangerous organisation in world history”.

When asked what his ‘Utopia’ consisted in, Chomsky told the same interviewer this:

I don’t have the talent to do more than suggest what seem to me reasonable guidelines for a better future. One might argue that Marx was too cautious in keeping to only a few general words about post-capitalist society, but he was right to recognise that it will have to be envisioned and developed by people who have liberated themselves from the bonds of illegitimate authority.

Noam Chomsky would hate to have it pointed out to him that he happens to be one of such people. Indeed, that there are only a few like him.

Based out of Bangalore, Anjan Basu freelances as a translator, literary critic and commentator. He can be reached at [email protected]