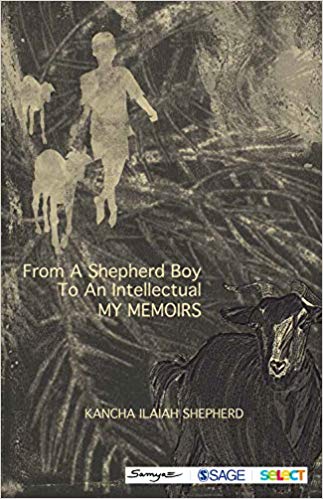

This is the Preface of the just released Autobiography of Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd entitled “From A Shepherd Boy To An Intellectual–My Memoirs”. Published by Samya/Sage (Select) New Delhi. Countercurrents reproduces the introduction.

PREFACE

I never intended to write a memoir. My two books Why I Am Not a Hindu and Post-Hindu India, generated debate and controversy among the Brahmin-Baniya readership and at the same time also inspired thousands of young people coming from the Dalitbahujan backgrounds. Even the Shudra upper castes like Kammas, Reddys, Marathas, Patels, Jats, among others, took a supportive stand. These two books divided the productive and unproductive forces on caste lines. Because of these books the whole question of production and caste culture came in for a live debate and in the process much ideological discourse got generated about the future course of Indian struggles and transformation.

If Ambedkar were to be alive he would have been happy that after Mahatma Phule and him a person from a shepherd community (Dhangar in the Maharashtra context) has taken up the battle at least a little bit further. However, he would have been unhappy that neither he nor Phule left their own life stories written by themselves, which may have told us something different. Even Mahatma Phule who deeply distrusted brahminic writing, had to have his life story told by Dhananjay Keer, a sympathetic Brahmin of Maharashtra. I, therefore, thought I should leave my own account of my life. Given the kind of attacks that the Brahmin-Baniya communities of the Telugu region launched against me recently, I thought I should complete this memoir as soon as possible. I have been living in an environment of attack on intellectuals fighting for equal rights of people. I have stood by the Dalitbahujan masses all my life. This led me to write it in a hurry.

In 2016–2017 much dust was raised mainly by two communities – the Brahmins and Baniyas – about my intension in writing my two books, which they rather strongly felt have changed the discourse about production relations and the caste system in India. Even within communist circles my books have become a bone of contention. Since both books dealt at length about the nature and character of the Hindu religion and its historicity, the right wing political forces – mainly Brahmins, Baniyas and Jains – working around the BJP took up a major campaign against my writing. It was in this context that the Arya Vysya community with the support of conservative Brahmins and the BJP launched a major agitation against me personally and also my books. In 2017 the Arya Vysya agitations and death threats created a national and international counter agitation. The university campuses played a key role, apart from the Dalitbahujan, progressive social forces in countering the Arya Vysyas and right wing forces.

This situation also led to several court cases against my books, particularly Post-Hindu India, though Why I Am Not a Hindu also came up for scrutiny in some of the petitions. The court cases involved the Supreme Court of India, the Joint High Court of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana states and also about half a dozen local court cases. In 2015 one of my articles ‘Is God a Democrat or Not? published in Andhra Jyothy, a popular Telugu newspaper, had to face a court case, and a famous High Court lawyer A. Satya Prasad, who is a progressive and stands for democratic values, got it quashed. As I am writing this preface I am going round the first class Magistrate Courts of Korutla, Jagtial district, and Malkajigiri, Hyderabad, and three other cases are pending in police stations. All of them are filed by the same Arya Vysya forces and when I go to attend the cases they try to attack me in the court premises itself. The attack on 22 November 2017 at Korutla court is well known. However, I have filed a quash petition in the Joint High Court of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana and the same A. Satya Prasad is arguing on my behalf. Since I have a lot of respect for the Indian constitution and the Indian judiciary I will go through the judicial process.

The Brahmin associations of the Telugu states in 2016 attacked my writings. They abused my name Ilaiah as an unworthy name, my caste as not worthy of respect. In order to answer them I had to add the word ‘Shepherd’ to my name, as a mark of my parental profession as it is a most respected profession globally, both spiritually and socially. It was at this stage I decided to write my memoir because the Brahmin-Baniya castes are respected by the lower castes even though they show disrespect to my caste people. In many parts of India the shepherding communities do not have any sense of being humiliated, disrespected and even abused. They still do not abuse the abuser. This is true of many other OBC communities. A sense of self-respect needs to be injected into their being through various modes of writing. Autobiography, memoir, and biography of people who fought against oppression, humiliation and exploitation are definitely better tools.

Many people from the Brahmin-Baniya castes have written about their own greatness in their autobiographies, in English and local languages. But I have not even seen a single autobiography of person born and brought up in the shepherd community in regional languages, particularly in Telugu, leave alone in English. And also I have no hope of somebody writing an authentic biography of mine from a lower caste background because they have not yet realized the importance of writing their own memoirs.

An interesting thing happened after Post-Hindu India was dragged to the Supreme Court of India by the Arya Vysya Sangham. On 12 October 2017 a three judge bench of the Supreme Court constituting the following judges gave a historic judgment. Chief Justice Dipak Mishra, Justice A. M. Khanwilkar, and Justice D. Y. Chandrachud stated:

We do not intend to state the facts in detail. Suffice it to say that when an author writes a book, it is his or her right of expression. We do not think that it would be appropriate under Article 32 of the Constitution of India that this Court should ban the book/books. Any request for banning a book of the present nature [Post-Hindu India] has to be strictly scrutinized because every author or writer has a fundamental right to speak out ideas freely and express thoughts adequately. Curtailment of an individual writer/author’s right to freedom of speech and expression should never be lightly viewed. Keeping in view the sanctity of the said right and also bearing in mind that the same has been put on the highest pedestal by this Court, we decline the ambitious prayer made by the petitioner.

The writ petition is, accordingly, dismissed.

This judgement gave not only to me but to Dalitbahujan writers and thinkers confidence that they can write their opinions without any fear of attack or ostracism. Writing is the only medium that can change the conditions of the oppressed Dalitbahujans. After Ambedkar, I took up this task, and this writing has to be done on a continuous basis, generation after generation.

There is no doubt that such writing generates fear among the oppressor caste forces. What I have realized in my lifetime is that caste-centred change is resisted more than class-centred change. This is because caste hegemony gets into the bloodstream of people born into those castes. So also caste inferiority gets into the bloodstream of the oppressed castes. Class inferiority could be easily overcome but not caste inferiority. Class exploitation could be easily fought but caste exploitation. That is the reason why caste struggle is more difficult than class struggle. Since caste is both cultural and economic, the fear of changing caste relations haunts much more than changing class relations.

Those castes that constructed indignity of labour both socially and spiritually feel terrible if the changes are on the cards. Hence the anger against my writing has come from all men (not so much women) who were born and brought up in Brahmin-Baniya communities, irrespective of their ideological location in their political lives. The fear of the basic unproductive castes is that their hegemony gets smashed if my writings are allowed to influence the social forces: castes, classes, groups, interests. It is so because I am a member of the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). The Backward Classes are the mainstay of the Hindu religion and they are the biggest pillars of the economic activity and service to the Brahmin-Baniyas.

Though Dalits are at the base of the Indian economic activity, by sheer numbers the OBCs, who have never challenged the Hindu system, are counted as gullible followers of Brahminism. Even if Dalits are given a separate nation, as Ambedkar demanded during the colonial times, the Brahmin-Baniya labour-free life can be lived with the services of the OBCs. If the OBCs move away from Hinduism, like Dalits are doing now in many areas, the very structure of Indian society will change. All the hopes of the oppressor castes will collapse swiftly.

Several groups took up a campaign that I am already a Christian convert and that is the reason why I am writing all these books. By writing this book I wanted to tell the nation that it is wrong. My critique of Hinduism, Brahminsm and Baniyaism is being done from my positioning as an OBC, who as I said in Why I Am Not a Hindu, is from a large community that has had nothing to do with Hinduism for millennia. But is it more ‘Indian’ than what the upper castes call their nationalism.

This memoir once again will relate that the Dalitbahujans of India historically are more nationalists than the castes that have not contributed to the basic production of India.

A memoir by and large deals with people, places, castes, communities, with whom an individual has interacted. In mine I have dealt with institutions, individuals, their behaviour with me, my work and also my intellectual being in an unconventional way.

Most of the interactions, happenings with individuals I have seen in relation to their caste background, not based on their individualism. Because of caste cultural training of people from their childhood individualism has not yet taken roots in India. By and large we are what we are based on, how we are trained in our caste culture in the childhood. I strongly feel that a keen love for equality and a fair promotion of talent are important for a nation to prosper and challenge the hegemonic countries in the world. My critique of Hinduism, Brahminism and Baniyaism are meant for evolving human society of equality in this country and making India a great nation. It is also meant to evolve democratic individualism in India. My purpose is my strength.

There were questions, when I was writing this book, whether the caste behaviour of individuals is the same everywhere in India. Particularly if the Brahmin-Baniya readers, who feel a serious critique of those caste cultural, academic and political behaviour in relation to me is generalized too sweeping because all over India these persons do not behave in the same way. Since these two—Brahmin, Baniya castes are the major hegemonic castes and they have a pan-Indian existence with the same caste name, they complain No . . . No . . . this behaviour cannot be generalized for every Brahmin or Baniya living in all parts of India. What they do not realize is that I am generalizing that behaviour based on my experience, interaction working with them, living with them, discussing and debating with them, wherever I did. I cannot talk about people I never met or worked with. That is what a memoir is all about.

This is not a research work on communities. Even the research work on a community or caste cannot study every individual of that community or caste and generalize that community’s culture, character, behaviour, attitude and so on. Those who do not agree with me have a right to do so. But they cannot stop me exercising my right to come to my own conclusions about communities and castes and their socio-economic and behavioural patterns. The way I want to come to a conclusion is based on my encounter with them and is entirely based on my personal relationship and understanding. This is also true of men and women. A woman’s conclusions cannot be questioned by men when they have no similar experience.

Subjective negativism may develop in an individual from an oppressed caste as against an oppressor caste. That is not unexpected. But the oppressor caste could wholly be subjective towards the oppressed castes, who form the base structure of the Indian society. There is a universally known character of a shepherd. When a shepherd sees a baby in the hands of a mother, whose life is in danger along with the baby, the shepherd knows how to mislead even the king who plans to kill that baby and the mother. That kind of misleading of the killer king is actually leading the humanity on a proper course of survival: development. As a community the shepherd community is known as the most honest and hard working. It is this community, the world over, known as the community that knows the truth better and lives for taking care of lost sheep. In India for millennia this community has been seen as worthless, wretched and stupid. All my life I lived to change this narrative. When writing the story of an Indian shepherd, I do not need a certificate from the community of priests, who never loved a sheep, never taken care of one in the whole history of this nation. They have no love lost for the shepherds, even now.

My generalizations in this book are purposive. Yes, they are biased to some extent to the shepherds, who established the base economy, culture, if not politics of the Indian society. When the whole community or caste remains oppressed in all spheres that generalization is certainly valid and in their own interest. No social transformer should depend on the opinion of a person from an oppressor caste or community. That is what I did all my life. This memoir also operates outside the framework of what is usually defined as autobiography, with dates, chronology, events, phases of life and so on. It is a memoir of a Shudra, people who are all over India, outnumber others, but are unknown in the written world of India.

The most known autobiography in India is that of Mahatma Gandhi, from a Baniya, vegetarian background. The other most known autobiography is that of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, who was to some extent a de-Brahmanized Brahmin (an un-Hindu in his own way, a meatarian, beefarain and an arch enemy of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh). Quite tragically no Shudra leader of a national stature has written an autobiography or memoir that I know of, at least. Mahatma Phule, Periyar Ramasamy Naikar, nor Narayanguru (all were OBCs) did not leave an autobiography of their own.

Ambedkar, the Indian messiah of the Dalitbahujans, did not leave his own account, but his biography, written by Dhananjay Keer, is a well-known book. Of late, many Dalit writers are writing their own autobiographies. But the Other Backward Classes have not even been doing that. In that sense mine is the first story of a Shudra, written in English, to tell the truth upside down from the point of view of the Gandhian truth and also the historical brahminical truth. That is the reason why I wrote a chapter ‘My Experiments with Untruth’ in this book. Truth and Untruth are two different and opposite values from the Dalitbahujan and Brahmin-Baniya points of view and value systems.

This book would not have been in this shape but for the support offered by my friends at Samya, particularly Mandira Sen, who took a personal interest in completing this book. Ever since I put my first book Why I Am Not a Hindu, into their hands, their editing has enriched my books and improved their readability. I thank Mandira Sen and the Samya team for all their editorial fine tuning work from the bottom of my heart. I also thank Sage for publishing this book jointly with Samya. I thank Mohasina Anjuman Ansari, research assistant at Centre for the Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, for help in writing this book.

I thank all my family members for helping me in various ways all my life. I thank all the productive castes and communities of India, whose labour power helped me to live in the higher educational institutions that have hardly done justice to their productive, ethic, culture and history.

I hope this memoir encourages many Shudras (OBCs) to write their own memoirs.

Hyderabad

29 January 2018

Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd

Prof. Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd Chairman T-MASS and political theorist.