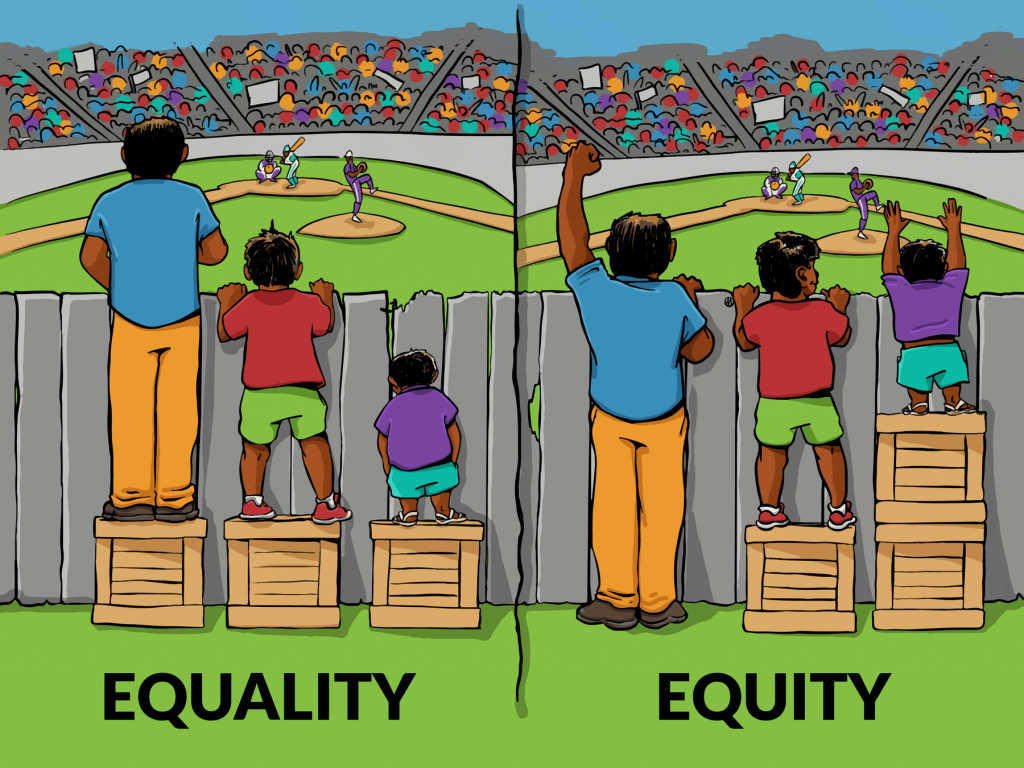

The decision of the Centre to provide for an additional 10% quota for the economically weaker section among upper caste in jobs and education is a misrepresentation of the idea of representation. Measuring social deprivation by economic standards is a caste-blind approach that usurps the spirit of positive discrimination to the socially and educationally backward caste for decades. The government would have to face the axe of the Supreme Court for its decision that contradicts the clauses of Articles 15 and 16 of the Constitution for giving extra representation to the over represented upper castes in jobs and education.

The terming of the Representation policies as ‘reservations’ for particular people in the name of caste is also a smear campaign launched by the nexus of mainstream media and upper caste ruling class.

The meaning of the Representation policies, that stands as a constitutional obligation of the state, has been misused and would further delay the progress of social justice in the country.

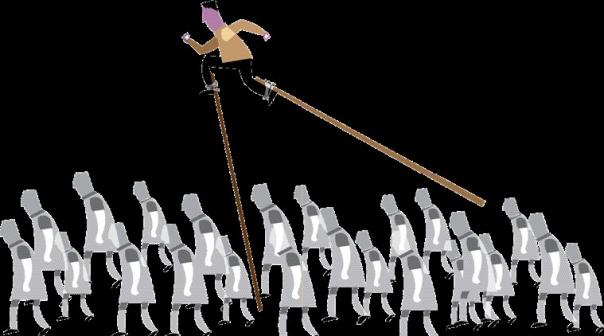

While affirmative action to the scheduled caste and tribes and the backward castes have been formulated after studies revealed that these groups are unrepresented and their representation would give a balance to the administration and governance, the current political spectrum, cutting across ideologies, believe that the representation policies are a poverty alleviation programme and the country has to do away with it to move faster. This approach stems from the myth of merit that the administration is callous due to representation given to the SC/ST and the OBCs. But it is a glaring truth that the rule of hierarchy still reigns in government jobs as the number of SC, ST and OBC workers diminishes up the ladder.

The Group A posts of the central government has a mere 12.06% of officers from SC, with 8.6% people from OBC, with the rest occupied by the upper caste. Also, a majority of government employees from SC fall in Group C jobs with 17.53%, says a report released by the Ministry of Social Justice in 2016. The most of which accounts for the job of cleaners, where people from SC constitute nearly 40%, according to a report tabled in the Parliament in 2012.

The government’s weird understanding of poverty with a cap of Rs 8 lakh is also problematic as it only give impetus to the upper caste who dominate every sphere of activity in the country. With the same logic the government is also trying to say that a Dalit earning more than Rs 8 lakh a year should choose not to avail the benefits of affirmative action.

It is also evident that the government and the ruling class is reducing the form of systemic oppression that hold sway in India that is prima facie a mix of caste and gender to a mere economic distress. The oppression faced by an upper caste poor man and a lower caste poor woman are different and contrasting on various heads. The structure to fight is multifaceted rather than monolithic.

Dr BR Ambedkar believed that a representative government was much better than an efficient government on the above line of thought. He fought tooth and nail to bring in separate electorates for the depressed classes, but fall short to the intimidation of Gandhi who sat on a fast unto death to pressurise Britain to roll back Ambedkar’s idea.

The Dalit emancipation needs to have strong mechanism in place in the form of separate electorates and any dilution would stall the process. Much evident is the present system of political representation, where members of the legislatures from SC, ST are viewed as mere party men and not the representative of the community they hailed from. And it was the system that Dr Ambedkar wanted to cease after 10 years.

Joel Thomas Mathews is a student of MA Women’s Studies at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad. Also worked as a content editor with ETV Bharat.