Introduction

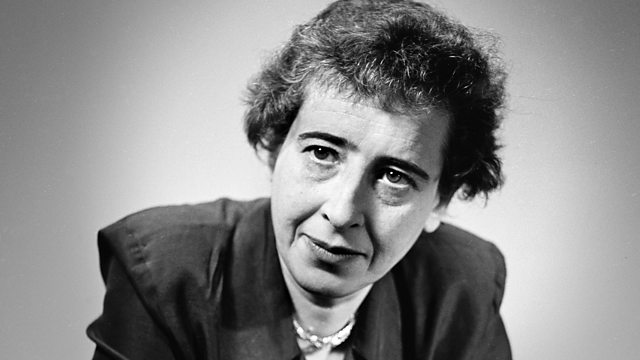

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) was a pupil of Edmund Husserl (1859– 1938), Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), and Karl Jaspers (1883–1969), three significant, prominent, 20th century German philosophers whose work grounded and remained noticeable in Arendt’s philosophy. Arendt’s philosophies also recall the German philosophical systems of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), G. W. F. Hegel (1770–1831), and have the courage to say, Karl Marx (1818–1883). Although Arendt’s philosophy does not necessarily resemble Kantian rationalism, Hegelian idealism, or Marxian dialectical materialism, she developed a philosophy that was every bit as systematic as these earlier German philosophies. Hannah Arendt’s work offers a powerful critical engagement with the cultural and philosophical crises of mid-twentieth-century Europe. Her idea of the banality of evil, made famous after her report on the trial of the Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann, remains controversial to this day. In the last few years, this dominant idea of ‘theory’ has been subjected to a robust challenge. In his recent book After Theory, Terry Eagleton has stated this challenge in a rather tongue-in-cheek way.

“The golden age of cultural theory is long past. The pioneering works of Jacques Lacan, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Louis Althusser, Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault are several decades behind us … Some of them have since been struck down. Fate pushed Roland Barthes under a Parisian laundry van, and afflicted Michel Foucault with Aids. It dispatched Lacan, Williams and Bourdieu, and banished Louis Althusser to a psychiatric hospital for the murder of his wife. It seemed that God was not a structuralist.

(Eagleton 2004:1).

Hannah Arendt was born in the German city of Hannover in 1906, to an assimilated Jewish family, and brought up mainly in the east Prussian city of Königsberg, now part of Russia. She recalled in a television interview in 1964 that ‘the word “Jew” was never mentioned at home. After Hitler became the chancellor of Germany in 1933, Arendt was briefly detained by the German authorities for gathering information, on behalf of the German Zionist Organisation, about how anti-Semitism was becoming official German policy. She felt compelled to leave Germany, first for France, where she worked for a Jewish refugee agency in Paris that was helping Jewish children and young people to make their way to Palestine, before being briefly interned in a concentration camp at Gurs at the foot of the Pyrenees after the German invasion of France in the summer of 1940. She ultimately made her escape to the USA in 1941. America would remain her home for the rest of her life.

Philosopher, Political Analyst, Biographer, and Writer

Arendt’s phenomenological roots (Husserl, Heidegger, and Jaspers) affect not only her philosophy but also her political and biographical work. Beginning with her doctoral dissertation published as Der Liebesbegriff bei Augustin (1929; St. Augustin’s Concept of Love) and afterward in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), On Revolution, (1963), On Violence (1970), and Crises of the Republic (1972), Arendt looked at, with new insights, some pivotal historical ideas and events. The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) endowed with Arendt identification as historian and political philosopher. In Origins (1951), Arendt analyzed totalitarian government systems’ rise focusing on Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. After the publication of Origins (1951), she received invitations to lecture at Princeton (1953), Berkeley (1955), and Chicago (1956) universities and joined the faculty of the New School of Social Research (1967). 1 Interspersed throughout her publications are short (with the exception of the over 300-page biography, Rahel Varnhagen: The Life of a Jewess, 1957/1997) biographical studies that represent another facet of her work and thought. In these biographical studies, Arendt analyzed individuals’ contributions with a goal of examining “how they were affected by historical times.” Arendt seemed to be particularly interested in individuals’ strengths and weaknesses during particularly distressing times. Finally, though seldom mentioned, but not without importance, Hannah Arendt was a poetess with a poet’s sensibility that appears even in her prose. “Poetry,” she said, “whose material is language, is perhaps the most human and least worldly of the arts, the one in which the end product remains closest to the thought that inspired it.

For Arendt, this awareness of the naivety of intellectuals in relation to the public world became a defining insight. Arendt’s vow to abandon the world of ideas in 1933 was, as she says, exaggerated. But even so, she never became a permanent member of a university faculty in North America. For much of her life in America she remained a kind of freelance journalist and social and political thinker. From 1944, she took on a role directing research for the Commission of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, a role that took her back to Europe after the war, and back into contact with Heidegger. Arendt also took on various roles as a visiting professor at institutions of higher education such as the New School for Social Research in New York and the Committee on Social Thought at Chicago University, and she was the first woman at Princeton University to become a professor. But Arendt remained, to borrow a phrase from the feminist thinker Gayatri Spivak (1942–), ‘outside in the teaching machine’. This perhaps shows her distrust for traditional methods of thinking and its institutions, as well as her desire to carve out a new, independent role for the intellectual in public culture. No doubt this was partly informed by Arendt’s experience of the depressing way in which many faculty members in German universities had shown little resistance to Hitler’s rise to power in the 1930s, and scant support for their Jewish colleagues who were banned from teaching.

Arendt’s life in America eventually saw her participating actively in American public life and its debates in the 1950s and 1960s about civil rights, civil disobedience and racial segregation, political corruption and the Vietnam War. In the first years after her arrival in America, though, when the war in Europe was still raging, Arendt took a strong and active role in the Zionist movement, urging the formation of a Jewish army to fight Hitler in her contributions to a German language newspaper published by the Jewish émigré community, Aufbau. Arendt was profoundly resistant to a view of the Jews as innocent victims of the Nazis, a view that she thought the Jews of Europe had taken on about themselves, and that she also thought was very damaging to their self-understanding and their political identity. She wanted to claim, instead, that Jews needed to take responsibility for their actions, rather than simply portraying themselves as innocent victims, or ‘lambs to the slaughter’. Joining the fight against Hitler as a unified Jewish force, thought Arendt, would mean that they took control of their destiny. The formation of a Jewish army might mean, she suggested in the title to one of her articles, ‘the beginning of Jewish politics’. Arendt was profoundly suspicious of any attempt to understand Jews as innocent ‘scapegoats’ for Germany’s problems, another assumption about totalitarian rule that she wanted to demystify. She nevertheless thought that this was a highly seductive interpretation of what had happened to them under Nazi rule. There is, she writes at the beginning of The Origins of Totalitarianism:

“a temptation to return to an explanation which automatically discharges the victim of responsibility: it seems quite adequate to a reality in which nothing strikes us more forcefully than the utter innocence of the individual caught in the horror machine and his utter inability to change his fate.”

(OT 1:6)

Hannah Arendt and Education

Although Arendt was as well versed in classical philosophy as in the 18th- and 19th-century French and German philosophers, it was not until her work observing and assessing the Eichmann trial and writing Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963) that Arendt, with her phenomenological underpinnings and perspective, looked to history and the philosopher of history, Hegel, to help her understand and explain Eichmann’s actions and the actions of others like him. Hegel posited individuals’ day-to-day activities move history forward. From the greatest to the lowest, responding to their own needs and desires, prejudices and preferences, the power they wielded or to which they succumbed, and their responses to social and physical environments and pressures account for history’s progress: “mankind ceases to be a species of nature, and what distinguishes him from the animals is no longer merely that he has speech…or reason…his very life now distinguishes him…his history.

During the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, in addition to teaching at the New School of Social Research and writing essays and books, Arendt ever more spoke as a guest lecturer in many colleges, universities, and other organizations. These were turbulent years in the United States; the Civil Rights Movement, legislation, and U.S. Supreme Court decisions resulted in repercussion. The Vietnam War and anti-war movement created division and dissension. The deaths of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and others, formed a sense of hopelessness for the future. Constantly thinking and writing about the social, political, and educational events and issues of her time, Arendt did not follow conventional wisdom and was sometimes misunderstood as when she published Eichmann (1963). In “Crisis in Education” (1958) and “Reflections on Little Rock” (1959), for example, Arendt measured the wider implications of the thoughtlessness she saw in Eichmann, the thoughtlessness of people in response to the issues and events that confronted them, and the consequences—intended and unintended—of national leaders’ and their opponents’—the extremists and radicals— actions on the left and right. Arendt found U.S. society’s problems in these years to stem from “a security hysteria, a runaway prosperity, and the concomitant transformation of an economy of abundance into a market where sheer superfluity and nonsense almost wash out the essential and the productive…and…the problem of mass culture and mass education.”36 One can see Arendt’s analysis of the world was without sentimentality or bias. She took this same kind of analysis into her posthumously published, The Life of the Mind (1978), where she dealt with the thoughtlessness present in her society.

Hannah Arendt’s conclusion in her chapter on education in ‘Between Past and Future’:

Education is the point at which we decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility hr it and by the same token save it from the ruin which, except for renewal, except hr the coming of the new and young, would be inevitable. And education, too, is where we decide whether we love our children enough not to expel. them from our world and leave them to their own devices, nor to strike from their hands their chance of undertaking something new? Something unforeseen by us, hut to prepare them in advance for the task of renewing a coininor1 world.

Interestingly, although Arendt was not an educator and wrote very little on educational issues, her writings address a wide array of political concepts-such as natality, action, freedom, equality, public space, and plurality-that are particularly relevant for democratic societies.

Hannah Arendt on Authority: Conservatism in Education Reconsidered,” follows and begins with the assumption that most conservative approaches to education emphasize the need to teach worthy subjects and fundamental moral values to the young. One rarely encounters a conservative educator who believes in providing students with opportunities for change and innovation. In contrast, I present Hannah Arendt’s conservatism as an exception to this trend and argue that her insights on authority need to be taken seriously by democratic educators. Although Arendt favors maintaining a traditional notion of authority in education, she also insists that teachers should foster the revolutionary and the innovative in children. In effect, she helps us bridge the gap between the old (tradition) and the new (change), a problem that has troubled educators for centuries. 1 also argue that, unlike the views of mainstream conservatives, Arendt’s conception of pedagogical authority has a number of important implications for democratic education. As such, her approach to education is not only much more convincing than mainstream conservative arguments, but it also constitutes a genuine contribution to the debate over the aims of schooling in a democratic society.

The Paradox of Natality

In the preface to her latest anthology of writings by and about women of color, GIoria Anzaldia shares the frustrations that emerged when her students confronted one another directly about racism and the politics of racial identity in a course she teaches on women of color in the United States. This was no abstract, depersonalized discussion; Anzaldia writes about her students of color ‘holding whites accountable’ for racism and about her white women students, in turn, ‘begging’ students of color to ‘teach them’ about racism and to tell them what they wanted whites to do about it. Describing the resistance of her students of color to the white students’ efforts to position them as the political conscience of the class, Anzaldia attributes their refusal to become engaged in ‘time-consuming dialogues’ with white women to “their hundred years’ weariness of trying to teach whites about Racism.

Most conservative approaches to education emphasize the need to teach worthy subjects and fundamental moral values to the young. For educators like Edward Wynne, the main mission of schools is to indoctrinate the young in the moral values of the great tradition.$ One rarely encounters a conservative educator who believes in providing students with opportunities for change and innovation. Since they disregard issues such as plurality, individual creativity, and critical citizenry, these educators, as Barbara Finkelstein and others have shown, cannot contribute much to the current debate on democratic education.

Hannah Arendt reiterated over and over: “Ta the extent that I wish to think I have to withdraw from the world.” Following Martin Heidegger, Arendt insisted that “thinking is always out of order,” because the “sheer activity” of thinking only gets under way when the so-called ordinary activities of everyday life are disrupted and interrupted. For Arendt, the life of the mind (vita contemplativa) is a “solitary” yet an intradialogic experience that happens outside, or beyond, the practical world of the everyday life {vita activa) one shares with others. Arendt contended the crisis in education related to three assumptions about education. “The first,” she said, “is that there [exists] a child’s world and a society formed among children that are autonomous and must insofar as possible be left to them to govern. Arendt contended the crisis in education related to three assumptions about education. “The first,” she said, “is that there [exists] a child’s world and a society formed among children that are autonomous and must insofar as possible be left to them to govern.”51 This assumption focuses too much on the child group and deprives children of the normal child-adult relationship. The second assumption Arendt connected to the education crisis concerned pedagogy, the science of teaching: “Under the influence of modern psychology and the tenets of pragmatism…(pedagogy) has developed into a science of teaching in general in such a way as to be wholly emancipated from the actual material to be taught.” The result is a deficiency in teachers’ content knowledge leaving students to their own devices and depriving teachers of the respect that comes with superior knowledge. The third assumption about education she critiqued and deflated advanced the notion “that you can know and understand only what you have done yourself…[and therefore] results in the substitution of doing for learning and of playing for working…[both attempt] to keep the older child…at the infant level.”

Conclusions

Arendt’s life spans the first three-quarters of the last century and at the centre of her life’s work and her lived experience are found the horrors that totalitarian rule inflicted on Europe. For Arendt, what went on in Germany between 1933 and 1945 and in the Soviet Union under Stalin was without precedent. These were events that defied any form of systematic categorisation, or in other words, any attempt to understand them by subsuming them under existing political categories. Arendt thought, for example, that any attempt to understand totalitarian rule using the classical political concept of tyranny risked distorting an understanding of what was radically new and unprecedented about totalitarianism. This radical newness of the totalitarian regimes made it extraordinarily difficult for existing theoretical and philosophical systems to cope with the task of accounting for them. Like many others of her generation, Arendt then turned to art, and in particular to narrative and storytelling, in order to come to some form of preliminary understanding of the nature of the acts of the totalitarian regimes, that often seem to border on the in comprehensible. Arendt was notoriously hostile, for example, to the feminist movement, and whenever she discusses the human individual in her work, that individual is always described as a ‘he’ or as a ‘man’. Arendt’s relation to feminism will be discussed in the final section, but since a major aim of this book is to recover the meaning of Arendt’s argument in its proper context, I have decided to echo Arendt in the main, and to use the masculine pronoun when describing the various characters and social personality types that people her work. At other points, though, when I have sought to suggest the usefulness of Arendt’s work for a feminist politics. Hannah Arendt collapsed, apparently of a heart attack, while entertaining friends. A physician who was called pronounced her dead. At her death Dr. Arendt was University Professor of Political Philosophy at the New School. At the same time Dr. Arendt was working on a major three‐volume work, “The Life of the Mind.”

“Hannah Arendt was a strong voice for sanity and reason in the world’s intellectual community, devoted not only to writing but to teaching,” Dr. John R. Everett, president of the New School, said yesterday. “She loved students, and she worked with them in a way few great scholars are able to do without being tyrannical or overbearing. Arendt was a critical thinker who was profoundly concerned with questions about personal responsibility for atrocity, with problems of international justice and crimes against humanity, as well as with philosophical questions about judgment. Ultimately, Arendt condoned a practice of judgment that took place in the bright light of public space; perhaps this idea might begin to offer us illumination once again.

References

- Seyfa Benhabib, “”judgment and the Moral Foundation of 1)olitics in Arendt’s Thought,” Political Theory, vol. 16, no. 1 (February 1988): 31.

- Parekh, Bikhu (1981) Hannah Arendt and the Search for a New Political Philosophy, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Villa, Dana (1995) Arendt and Heidegger: The Fate of the Political, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Kateb, George (1984) Hannah Arendt: Politics, Conscience, Evil, Oxford: Martin Robertson.

- Passerin d’Entrèves, Maurizio (1994) The Political Philosophy of Hannah Arendt, London and New York: Routledge

- Disch, Lisa (1996) Hannah Arendt and the Limits of Philosophy, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Bernstein, Richard J. (1996) Hannah Arendt and the Jewish Question, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bromwitch, David (1998) Disowned by Memory: Wordsworth’s Poetry of the 1790s, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Burke, Edmund (1999 [1790]) Reflections on the Revolution in France, in Isaac Kramnick (ed.), The Portable Edmund Burke, London: Penguin.

- Butler, Judith (2004) Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence, London and New York: Verso.

Biography

I Pravat Ranjan Sethi finished my studies from Centre for Historical Studies, JNU, New Delhi, at present teaching at Amity University. My keen area of interest is Modern History especially Nationalism, Political History& Philosophy, Critical Theory and Social Theory.