“Your honour, I represent the United States government”. The Westminster Magistrates Court had been left with little doubt by the opening words of the legal team marshalled against the face of WikiLeaks. Julian Assange was being targeted by the imperium itself, an effort now only garnished by the issue of skipping bail in 2012. Would the case on his extradition to the US centre on the matter of free speech and the vital scrutinising role of the press?

Thomas Jefferson, who had his moments of venomous tetchiness against the press outlets of his day, was clear about the role of the fourth estate. A government with newspapers rather than without, he argued to Edward Carrington in 1787, was fundamental so long as “every man should receive those papers and be capable of reading them.” To Thomas Cooper, he would write in November 1802 reflecting that the press was “the only tocsin of a nation. [When it] is completely silenced… all means of a general effort [are] taken away.” The press provided the greatest of counterweights against oppressive tendencies, being the “only security” available.

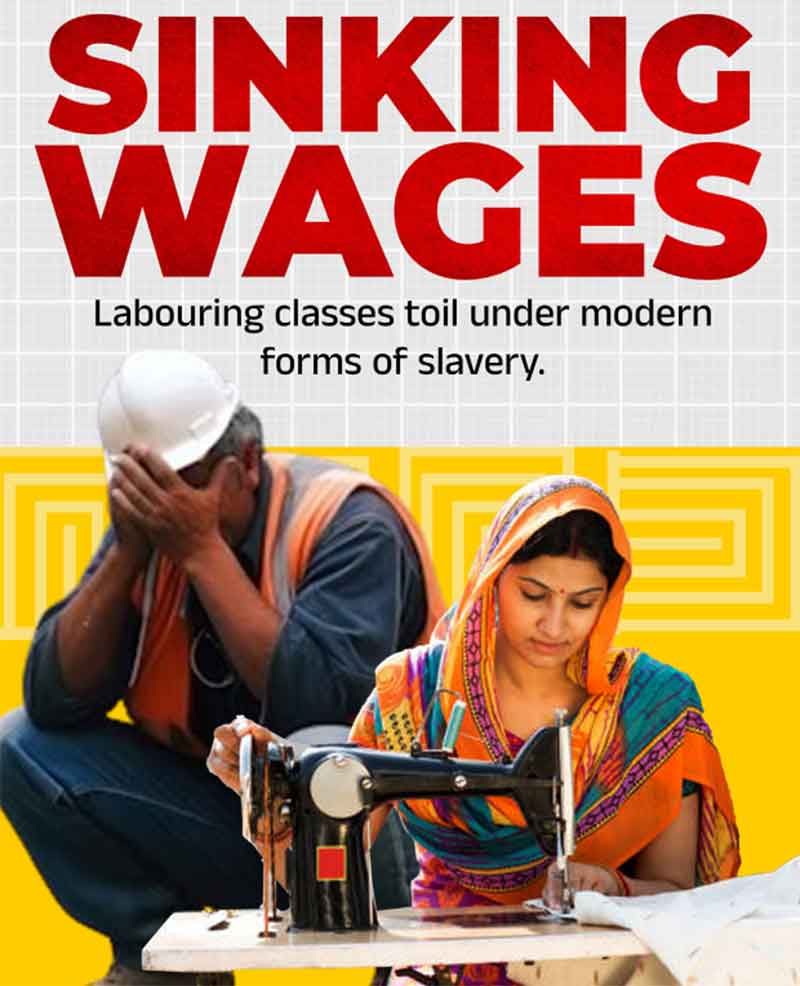

Not so, now. The fourth estate has been subjected to a withering. The State has become canny about the nature of the hack profession, providing incentives, attempting to obtain favourable coverage, and, above all, avoiding dramatic reforms where necessary. An outfit like WikiLeaks is a rebuke to such efforts, to the hypocrisy of decent appearances, as it is to those in a profession long in tooth and, often, short in substance.

It has logically followed that WikiLeaks, the enemy of the closed press corps and an entity keen to remove the high priests of censorship, must be devalued and re-labelled. This has entailed efforts to delegitimise Assange and WikiLeaks as those of a rogue enterprise somehow detached from the broader issue of political reportage. In this, traditional media outlets and the security establishment have accommodated each other; the State needs secrets, even if they rot the institutional apparatus; exposing abuses of power should be delicate, measured and calm. Scandals and embarrassments can be kept to a minimum, and the political system can continue in habitual, barely accountable darkness.

The indictment against Assange is the clearest statement of this strategy. It insists on shifting the focus from publication and press freedoms, which would pit the legal wits of the prosecution against the First Amendment, to the means information is obtained. Unscrupulous method, not damning substance, counts. In this case, it is computer intrusion laced with the noxious addition of conspiracy, a criminal concept vague, flexible and advantageous to the prosecution. The other side of the bargain was, the document alleges, Chelsea Manning, who thereby gathered the “classified information related to the national defense of the United States” pursuant to a pass word cracking pact, relaying it to WikiLeaks to “publicly disseminate the information on its website.”

A delighted Hillary Clinton, as she has always done with Assange, revelled in the prosecutorial brief, approving of an approach she could scant improve upon. At a New York speaking event, with husband Bill also in attendance, she suggested that journalism and Assange were matters to disentangle, if not divorce altogether. “It is clear from the indictment that came out that it’s not about punishing journalism, it’s about assisting the hacking of the military computer to steal information from the US government”. Call it something else, and the problem goes away. “The bottom line is that he has to answer for what he has done, at least as it’s been charged.”

West Virginia Democratic Senator Joe Manchin went one better than Clinton on John Berman’s New Day on CNN, doing away with any niceties, or impediments, British justice might pose to extradition efforts. “We’re going to extradite him. It will be really good to get him back on United States soil. So now he’s our property and we can get the facts and truth from him.” The Senate Intelligence Committee vice chair Mark Warner has similarly given the hurry on to British courts to “quickly transfer” Assange in an effort to finally give him “the justice he deserves”. New York Senator Charles Schumer, who obviously thinks the Constitution is irrelevant in this whole affair, simply wants red tooth in claw revenge for Assange’s “meddling in our elections on behalf of Putin and the Russian government”. To Schumer, the issue of a security breach seems less important than avenging the lost Democratic cause against Donald Trump.

Media coverage of Assange’s efforts over the years have often centred on the tension between the mind blowing “scoop” and the pilfering “hack”. Scoop Assange is to be praised; Hack Assange is to be feared and reviled. The paper aristocrats such as The Washington Post and The New York Times have blown hot and cold on the subject. One study from 2014 in the Newspaper Research Journal, in assessing publications run in the two over the course of the Cablegate affair, showed a rejection on the part of The Grey Lady of WikiLeaks as a journalistic outfit, with the Post taking a different view.

The fault lines are now sharper than ever. Assange’s arrest has done much to out the security establishment gloaters. Their tactic is one of personalising character and defects, as if that ever made a difference to the relevance of an idea. Michael Weiss, writing for The Atlantic, is characteristically obscene, and does everything to live up to the national security establishment he praises. Assange was a man who “reportedly smeared faeces on the walls of his lodgings, mistreated his kitten, and variously blamed the ills of the world on feminists and bespectacled Jewish writers”. As he was pulled out of the Ecuadorean embassy he looked “very inch like a powdered-sugar Saddam Hussein plucked straight from his spider hole.”

This grotesque exercise of equivalence – Assange the cartoonish beardo on par with a murderous dictator – has been supplemented by a general air of mockery, some of it more venal than others. Such behaviour has always been music to those who believe in the sanctity of the state. Guy Rundle of Crikey noted the same tendency of many a hack who had gathered outside the court to cover Assange’s trial. Their behaviour, in mocking Assange the man rather than Assange the publisher, “essentially validated every critique of mainstream media that WikiLeaks has ever made: that the profession is full of natural psychopaths, who spruik cynicism and call it even-handedness, who speak power to truth, who wilfully mistake the adrenaline rush of the micro-scoop and the petty scandal for genuine contestation.”

In this war of language, the treatment of Assange can only be seen as one thing: an act of muzzling a publisher framed as a computer security breach. In so doing, it criminalises the very act of investigate journalism, the sort that actually exposes abuses of power rather than meekly accommodating them.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]