Widespread “increases in extreme heat” due to climate crisis could bring unprecedented risks to the U.S. in coming decades, warned a new study.

By 2050, hundreds of U.S. cities could experience an entire month each year with U.S. “heat index” temperatures above 100F (38C) if nothing is done to check emissions and the consequent climate crisis, said the study report by the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS).

In the U.S., the National Weather Service (NWS) heat index scale starts topping out above temperatures of 127F (52C), depending on the combination of temperature and humidity.

The report – “Killer Heat in the United States: Climate Choices and the Future of Dangerously Hot Days (2019)” – by Kristina Dahl, Erika Spanger-Siegfried, Rachel Licker, Astrid Caldas, John Abatzoglou, Nicholas Mailloux, Rachel Cleetus, Shana Udvardy, Juan Declet-Barreto and Pamela Worth provides a detailed view of how extreme heat incidents caused by dangerous combinations of temperature and humidity are likely to become more frequent and widespread in the U.S. over this century.

Few places would be unaffected by extreme heat conditions by 2050 and only a few mountainous regions would remain extreme heat refuges by the century’s end, said the report.

The report also describes the implications for everyday life in different regions of the U.S.

The report said:

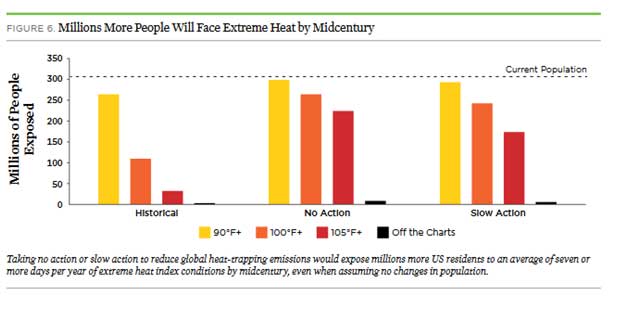

“As extreme heat grips more of the country, growing numbers of people would be exposed to dangerous conditions (Figure 6 above). Based on 2010 population data, and assuming no changes in population size or distribution, the number of people in the United States exposed to an average of 30 or more days per year with a heat index above 105°F would increase roughly 100-fold, from just under 900,000 historically to more than 90 million — or roughly 30 percent of the population — in the no action scenario. … By midcentury, more than 6 mil-lion people — equivalent to roughly the entire population of Missouri — would experience such conditions.”

The scientists have analyzed where and how often in the contiguous U.S. the heat index — also known as the National Weather Service (NWS) “feels like” temperature — is expected to top 90°F, 100°F, or 105°F during future warm seasons (April through October).

While there is no single standard definition of “extreme heat,” the scientists have referred to any individual days with conditions that exceed these thresholds as extreme heat days.

They have analyzed the spread and frequency of heat conditions so extreme that the NWS formula cannot accurately calculate a corresponding heat index. The “feels like” temperatures in these cases are literally off the charts.

The scientists have conducted this analysis for three global climate scenarios associated with different levels of global heat-trapping emissions and future warming.

The report said:

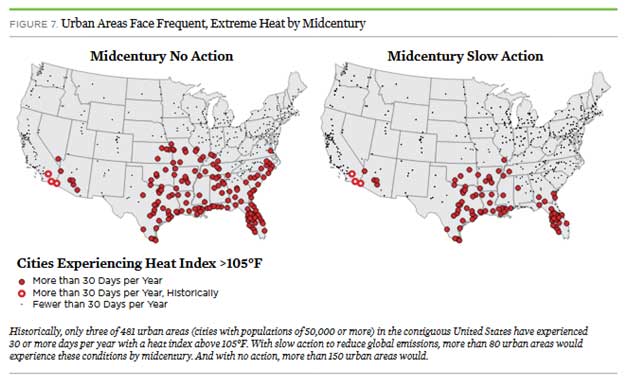

“Historically, 29 of 481 U.S. urban areas have experienced 30 or more days with a heat index above 100°F. With no action to reduce heat-trapping emissions, that number would rise to 251 cities by midcentury and include places that have not historically experienced such frequent extreme heat, such as Cincinnati, Ohio; Omaha, Nebraska; Peoria, Illinois; Sacramento, California; Washington, DC; and Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Nearly one-third of all urban areas — 152 out of 481 — would experience an average of 30 or more days per year with a heat index above 105°F, compared with just three historically.”

Cities’ unique land surface properties tend to make cities hotter than the surrounding areas. The phenomenon is known as the urban heat island effect. Cities contain relatively fewer shade-providing trees and an abundance of heat-retaining materials and surfaces, such as asphalt, cement, and pavement. The extra heat absorbed during the day is then re-radiated at night, keeping air temperatures in urban areas up to 22°F warmer than their surroundings. Moreover, nighttime air-conditioning releases additional heat into the city environment.

The study results show that “even by midcentury, cities throughout the country can expect frequent, intense heat to a degree that is historically unprecedented. These increases in urban heat will likely be compounded by … the urban heat island effect. … During heat waves, the urban heat island effect can be particularly harmful, as it reduces or eliminates the cooler hours when people can get physical and mental relief. Not surprisingly, violent crime often spikes in cities during heat waves. While this analysis only examined daily maximum heat index values, nighttime conditions — when the heat index is most likely to be at a minimum — are particularly important in determining the overall health impacts of an extreme heat event in cities.

Rapid action to limit the suffering

The report said:

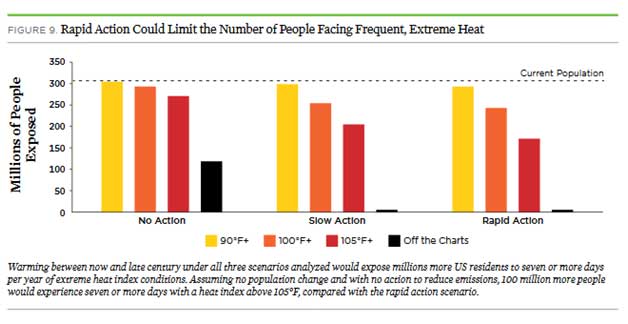

“Steep, rapid emissions reductions that result in future warming of 2°C or less would result in roughly half as many days with a heat index above 105°F nationwide, and about 125 million fewer people would be exposed to a month or more of such conditions, compared with the no action scenario. If aggressive measures are taken to bring down global heat-trapping emissions, roughly 114 million people in the United States — the equivalent of the populations of California, Florida, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia combined — would avoid exposure to the equivalent of a week or more of off-the-charts conditions.”

With both heat and population on the rise, the scientists expect many more people would be harmed. But some are more vulnerable to heat today and would be exceptionally so in an overheated future.

In the report, the scientists have outlined some of the implications for key overlapping segments of the U.S. population.

Outdoor workers

The report said:

By midcentury, “millions of outdoors workers already at elevated risk of heat stress including construction workers, farm workers, landscapers, military personnel, police officers, postal workers, road crews, and others would face greater challenges. Construction workers, who currently account for about one-third of occupational heat-related deaths and illnesses, may be at particular risk. For example, Texas and Florida, two states with some of the highest proportions of people employed in the construction sector, are poised to experience an additional month’s worth — or more — of days with a heat index above the worker-safety threshold of 90°F in an average year by midcentury. Similarly at risk are those employed in the agriculture, fishing, forestry, and hunting sectors, which account for about 20 percent of heat-related deaths and about 10 percent of heat-related illnesses reported to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). These workers will experience more risk even by midcentury. Much of this outdoor work, including agricultural work and roofing, requires being in direct sun, often for extended periods of time. Exposure to direct sun can raise heat index values by as much as 15°F. Within this sector, migrant farm workers face significant barriers to preventing heat-related illness. These workers often lack access to regular breaks, shade, medical services, health insurance, and training in prevention techniques. Despite clear risks, some agricultural business models make occupational heat-related injury and illness more likely by creating incentives for workers to push themselves beyond safe limits. For example, farm workers are often paid by the amount they harvest, which incentivizes them to skip breaks and overexert themselves. Heat-related illness is almost certainly underreported among migrant farm workers, as they are less likely to report their symptoms to supervisors and more likely to self-treat. One reason for the underreporting is that noncitizens or undocumented workers may fear punitive action upon reporting a workplace injury or illness and have little to no recourse.”

On the issue of labor capacity and productivity, the report said:

“Evidence suggests that, in addition to direct health impacts, increasingly extreme heat has already reduced global labor capacity, as it is more difficult to do the heavy work associated with industries such as agriculture and construction when it is extremely hot. Continued warming throughout the 21st century is projected to further reduce labor capacity and productivity. By the year 2100, estimates for the no action scenario suggest that lost labor hours would represent more than $170 billion in lost wages.”

People with low income or experiencing poverty

The report said:

“Even within a given setting, such as a city, vulnerability to heat is not equally distributed. Centuries of social discrimination and subsequent uneven opportunities for economic advancement have forced part of our population — disproportionately minorities and people experiencing poverty — into a state of heightened exposure and vulnerability to climate-related threats. U.S. residents who are not white, have low or fixed incomes, are homeless, and those in other historically disenfranchised groups are particularly at risk of heat-related illness and injury for a multitude of reasons, including lack of access to air-conditioning or transportation to cooling centers and residence in the hottest parts of cities.”

The report cited the 1995 Chicago heat wave that claimed the lives of more than 700 people, which is seen as not simply a natural disaster, but a societal one as well. The isolated, elderly African Americans suffered a disproportionate death toll because they were unable to flee overheated, non-air-conditioned apartments.

The report said:

“With one in three households in the United States already struggling to afford the cost of energy and few state-level policies banning utility disconnection during extreme heat events, the inability to pay for air-conditioning also raises the risk of heat-related illness for low-income people and families. Socioeconomic status is consistently identified as a factor in heightened heat health risk.”

The report recommended following actions [cited in brief]:

- The federal government must invest in scientific research, data, tools, and public communication related to extreme heat risks and protective actions, including fully implementing the NWS Weather-Ready Nation Strategic Plan.

- State and local governments will need to invest in developing localized heat adaptation plans and heat emergency response plans, especially in places that are unaccustomed to heat but will increasingly be at risk.

- Federal and state governments should expand funding for programs to provide cooling assistance to low- and fixed-income households, especially for elderly people and those with medical conditions.

- State utility regulators and legislators should require utilities to provide uninterrupted power service for residents, especially for elderly adults, sick people, and people with disabilities during periods of extreme heat.

- Congress should direct OSHA to set health-protective national occupational heat standards for outdoor and indoor workers under the Occupational Safety and Health Act.

- Federal, state, and local authorities should set standards and provide incentives for utilities, businesses, and homes to increase reliance on renewable energy, energy efficiency, energy storage, and microgrids.

- The federal government should increase efficiency standards for refrigerators and air conditioners and implement regulations to phase out use of hydrofluorocarbons, which are powerful heat-trapping gases used in these appliances, as agreed under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

- Utilities should implement flexible demand solutions that help shift demand away from times of peak energy consumption, such as that which might occur during extreme heat days.

- Utilities should invest in increasing the resilience of the electricity system by protecting generation, transmission, and distribution systems from heat-related threats, such as droughts and wildfires.

The report said:

“If we are serious about keeping people safe in the long term from extreme heat, the most consequential thing the world’s wealthiest nations (including the United States) can do is make deep cuts in our heat-trapping emissions and continue to implement and strengthen the Paris climate agreement.”

The report’s other recommendations include:

- An economywide price on carbon to help ensure that the costs of climate change are incorporated into our production and consumption decisions and encourage a shift away from fossil fuels to low-carbon energy options. Revenue from carbon-pricing policies can be used to support investments in energy efficiency, low-carbon technologies, adaptation, energy rebates for low-income families, and transition assistance for fossil fuel–dependent workers and communities.

- A low-carbon electricity standard that helps drive more renewable and zero-carbon electricity generation and helps deliver significant public health and economic benefits.

- Policies to cut transportation sector emissions, including increasing fuel economy and heat-trapping emissions standards for vehicles; increased investment in low-carbon public transportation systems, such as rail systems; replacing gas-powered public bus fleets with electric bus fleets; incentivizing deployment of more electric vehicles, including through investments in charging infrastructure; and research on highly efficient conventional vehicle technologies, batteries for electric vehicles, cleaner fuels and emerging transportation technologies.

- Policies to cut emissions from the buildings and industrial sectors, including efficiency standards and electrification of heating, cooling, and industrial processes.

- Policies to increase carbon storage in vegetation and soils, including through climate-friendly agricultural and forest management practices.

- Investments in research, development, and deployment of new low-carbon energy technologies and practices.

- Measures to cut emissions of methane, nitrous oxide, and other major non-CO2 heat-trapping emissions8. Policies to help least developed nations make a rapid transition to low-carbon economies and cope with the impacts of climate change

Extreme heat and human health

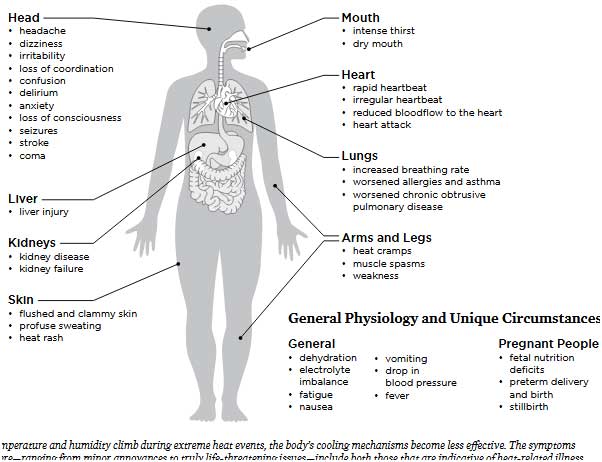

To show reactions of extreme-heat on human health, the report presented the following diagram:

During extreme heat events, the body’s cooling mechanisms become less effective. The symptoms shown here — ranging from minor annoyances to truly life-threatening issues — include both those that are indicative of heat-related illness and those that are signs of pre-existing conditions exacerbated by extreme heat. SOURCES: BASU ET AL. 2012; BECKER AND STEWARD 2011; CURRIERO ET AL. 2002; DONOGHUE ET AL. 1997; GARCÍA-TRABANINO ET AL. 2015; GLAZER 2005; LUBER AND MCGEEHIN 2008; LUGO-AMADOR, ROTHENHAUS, AND MOYER 2004; AND SEMEZA ET AL. 199