Australia has always nursed a contradictory, repressive relationship with its Pacific neighbours. Being a satrap of great powers, it has performed the role of gate keeper and monitor of regional instability, a condescending, often paternalistic agent. At stages, it has also entertained more direct colonial interests. For almost seven decades, Australia controlled Papua New Guinea, assuming power over the former British colony of Papua in 1906.

The conclusion of the First World War saw Australia draw in more former colonial territories once under German control, including German New Guinea. In Papua, stiff British tradition prevailed under the guidance of Hubert Murray. As Murray’s entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography goes, “Although aware that in some British colonies attempts were being made to rule through customary laws and to use influential villagers on local courts, Murray maintained the English-Australian legal system.” In New Guinea, the emphasis was on the enthusiastic and fairly ruthless exploitation of the indigenous population for economic gain.

The initial defeat of Australian forces in the Pacific by Japan brought a brief halt to its colonising hubris. After the Second World War, the colonising drive reasserted itself, this time in the guise of modernisation. Paternalism was enforced; theories of development were implemented.

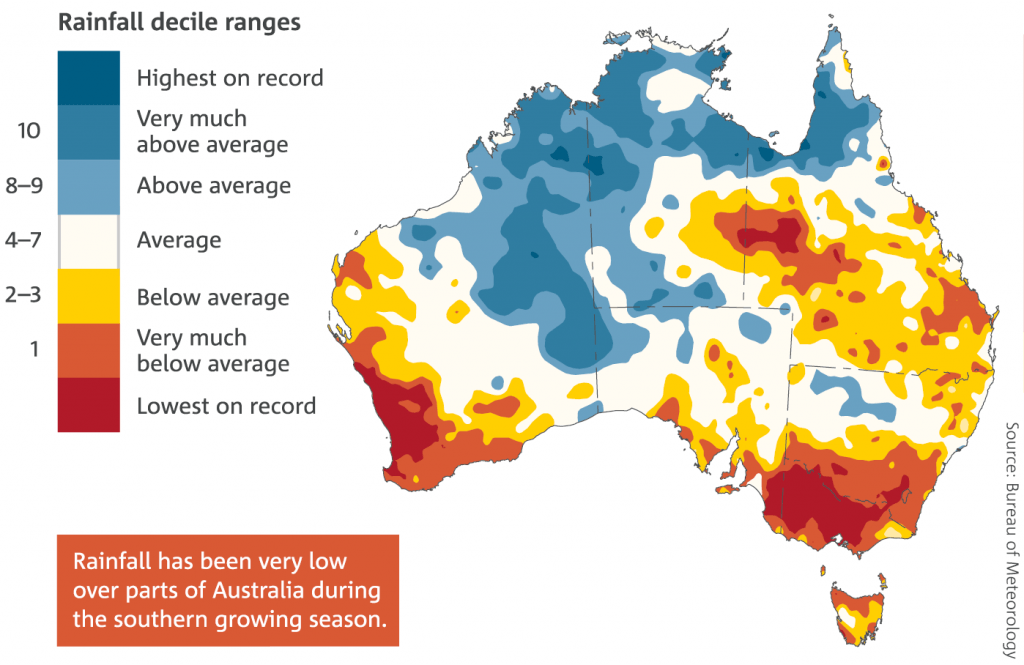

Little wonder, then, that Australia has a relationship of bleak contradiction with its neighbours, hovering between that of subsidising supporter and interfering father. But Australia now finds itself as the state seemingly out of step with the modern age. Climate change remains at the forefront of Pacific nations, a terrifying, existential threat that promises a liquid, submerged future. The government of Scott Morrison, by way of contrast, remains irritated by such notions of a warming earth and the growing number of doomed species. There is mining to be done, coal reserves to be extracted. The plunderer, in short, remains enthroned in Canberra.

What Morrison has instead done is to offer a package of $500 million, announced ahead of a meeting of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) Leaders Meeting, to take place at Tuvalu on Wednesday. According to Alex Hawke, Australia’s Minister for International Development and the Pacific, this constituted the “most amount of money Australia has ever spent on climate in the Pacific”.

The amount did little to inspire the popping of champagne corks through the region: the package was an accounting readjustment on existing spending arrangements and aid programs, despite Hawke’s suggestion that the aid budget had remained unaltered. Amidst such voodoo budgeting, Prime Minister Morrison insisted that the commitment highlighted “our commitment to not just meeting our emissions reductions obligations at home but supporting our neighbours and friends”.

In a sparse media statement on August 13, Morrison confirmed that he would “continue to work with our partners to build a Pacific region that is secure strategically, stable economically and sovereign politically.” Lip service was paid to the Blue Pacific narrative – the acknowledgment of shared ocean resources, geography and identity – and the Boe Declaration. Morrison gave the latter the most cursory of mentions, a conscious understating of the declaration’s acknowledgement that “climate change remains the single greatest threat to the livelihoods, security and wellbeing of the peoples of the Pacific and our commitment to progress and implementation of the Paris Agreement”.

Pacific Island leaders, however, are keen to remind their Australian counterpart that the sum of money dressed up as improving resilience in the face of climate change should not be taken to be an indulgence of polluting dispensation. As Tuvalu Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga explained, “No matter how much money you put on the table, it doesn’t give you the excuse not to do the right thing.” That right thing would be to reduce emissions, “including not opening your coal mines”.

Tuesday’s meeting of the Pacific small island states yielded a declaration less than musical to Morrison and his cabinet, a direct scorning of Australia’s environmental policy in calling for “an immediate global ban on the construction of new coal-fired power plants and coal mines” and the urging of all countries “to rapidly phase out their use of coal in the power sector”.

Morrison prefers to focus on the influence of that other C word, China, and the increasingly unhinging need to curb its influence. Pacific governments already owe Beijing some $US1.3 billion, a debt arrangement causing beads of sweat to form on the brows of Australian diplomats. But the Pacific family remains divided in their interests. The Solomon Islands, for instance, is warming to reconsidering its recognition of Taiwan as a separate, independent state, a point of some concern to Morrison, who wishes Taiwanese recognition to be a continuing policy.

In June, Solomon Islands’ Prime Minister Manasseh Sogovare went so far as to conduct a fact-finding tour of various neighbours with close China ties. In the words of a government law maker, John Moffat Fuqui, the taskforce would assess “the kind of development relations they have, the kind of assistance they get, the conditionalities or lack of conditionalities they might have, the kind of governance”. Nauru’s President Baron Waqa will not have a bar of it. “Taiwan is a very, very strong partner with those of us in the Pacific.”

Where the Morrison government hopes to be most mischievous in tampering with the PIF agenda remains climate change. In the realm of foreign policy, the Australian prime minister is hoping to have it both ways: placate, even bribe regional leaders into thinking that some climate change policy is chugging away, while maintaining the emissions schedule back home. To do so, Australian delegates have taken liberties in an annotated draft of the Pacific Islands Forum declaration. The August 7 comments ruthlessly excise references to climate change, carbon neutrality, the 1.5C limit in temperature rise, phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and a ban on new coal power plants.

The findings of the International Panel on Climate Change’s report on 1.5C are also given the heave-ho, with suggestions that Australia might “recognis[e] the information” without endorsing assessments that a fall of global emissions by 45 percent by 2030, with the attaining of carbon neutrality by 2050, had to take place for the limit of 1.5C to achieved. In the opinion of a regretful Hilda Heine, president of the Marshall Islands, “We would be lying to say we’re not disappointed, extremely disappointed.”

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER