Around a month ago, a workshop intended to address the gender gap in the sciences called Pressing for Progress 2019 was held at the University of Hyderabad (UoH). Early this October, Telangana Today reported that the UoH Vice Chancellor Appa Rao Podile addressed the attendees, sharing with them his thoughts on the conference and its aims.

I read this with some consternation. The Vice Chancellor’s name was not unfamiliar to me, and indeed, many of my colleagues. His infamy owes largely to his involvement in the institutional murder of Dalit scholar Rohith Vemula, who in the face of severe caste-based discrimination at the hands of the administration, took his own life in January 2016, a fact taken notice of by scholars across the globe. His suicide triggered a wave of protests and demonstrations across the country, and at the UoH itself these protests were quelled by violent police action. An independent fact-finding report by Profs. Suvrat Raju (ICTS-TIFR), Prajval Shastri (IIA), and Ravinder Banyal (IIA) concluded in no uncertain terms that the UoH administration, of which the Vice Chancellor was the head, bore the lion’s share of the blame for conflict, writing

“… we feel that it would help greatly if Prof. Appa Rao Podile were to voluntarily step down from his position as vice chancellor. As the head of the administration, he must accept responsibility for its multiple failures … we do not see how Prof. Appa Rao can possibly contribute positively to the University in the current polarized atmosphere. His very presence as vice chancellor has led to a sustained conflict that has embarrassed the University.”

In addition to this, UoH employees have brought forward explosive allegations of corruption and against the Vice Chancellor, alleging his involvement in “illegal appointments, unsanctioned posts, financial corruption, illegal nexus with those accused of fraud, [and] shielding alleged sexual offenders”.

The very same Prof. Shastri, one of the authors of the aforementioned fact-finding report, was the host of Pressing for Progress 2019, a conference dedicated to understand the origins of the “persistent gender gap in the physics profession in India” and “deliberate on ways of promoting gender equity”. This was supposed to be a progressive workshop, an important first step towards gender equality at least within the physical sciences. How, then, could Prof. Shastri and the other organisers allow the well to be poisoned thusly, by letting the Vice Chancellor take the stage? What sort of message does this send to academics from underrepresented groups, who are almost certainly insecure of their own position in the academy, about its commitment to securing for them a safe place in it?

The most charitable interpretation of this turn of events is pragmatism, that poster-child of liberal thought. “It is better,” we will no doubt be told, “to accept some indignities along the way if it means being able to start a conversation! And what would you rather we do? Not organise a conference like this? That would be the worst imaginable situation, where people aren’t talking about this issue!”

Of course, we’ve heard these arguments before. Liberalism prioritises pragmatism to the point of allowing itself to be dragged towards the political right on every issue, since its commitment is fundamentally not to any notion of justice but to “democratic” and “transparent” processes, to ideals untethered to any material circumstances; over time and unbeknownst to itself, it inevitably turns more grotesque and incoherent.

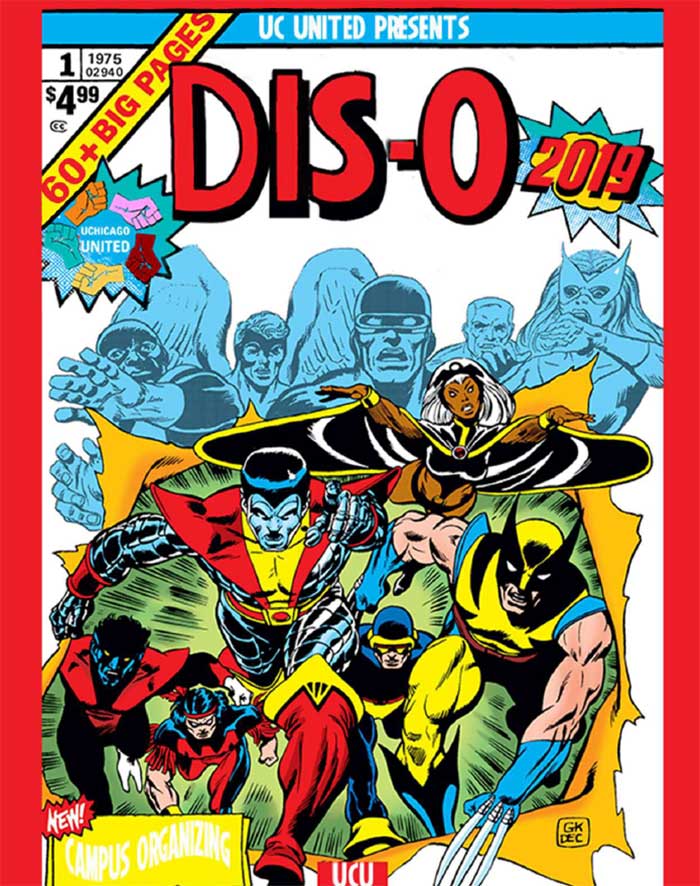

I don’t want to dwell too much on this example. I merely bring it up because it offers us a recent example of the lack of institutional memory. Indeed, this is a problem plaguing the academy, not just in India but across the globe, especially when it comes to instances of sexual harassment or the treatment of religious and ethnic minorities. In this context, I was pleased to see UChicago United’s 2019 Dis-Orientation Book (DisO), a 76-page guide to incoming students that prominently discusses the history of the University of Chicago. Referring unambiguously to this lack of institutional memory, the authors write:

“It can be so easy to repeat what has already been done and lose the opportunity to learn from and build upon what came before. Make no mistake: interrupting the passage of intergenerational knowledge is within the administration’s interests… Dis-orientation is more than just an indictment on the University and its oppressive ways. It is a starting point to understanding how we as university students are complicit in ways that we may not even know.”

A light-hearted, pop art aesthetic accompanies otherwise serious discussions of the University’s relationship with socio-political movements outside its walls, the question of what a university should look like and what values it ought to uphold, the role of the police on campus, the University’s relationship with the neighbourhoods around it, its stance on immigration, and its history in relation to race, labour, and LGBTQ+ movements.

The question of what role university spaces play in society and politics is one that visits us constantly, given the scale and magnitude of student unrest on campuses just in the last five years. For the University of Chicago, the Kalven Report, authored in 1967 in response to widespread protests against the Vietnam War, would supply the university with the position it takes on social and political issues to this day, namely that there is

“… [a] heavy presumption against the University taking collective action or expressing opinions on the political and social issues of the day, or modifying its corporate activities to foster social or political values, however compelling and appealing they may be.”

The Kalven Report has been invoked, in the past and to this day, to justify a refusal to divest from apartheid South Africa, companies doing business in Darfur, fossil fuel conglomerates, and companies profiting from Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories. The DisO points out, significantly: “this inaction is itself a political position.”

While the Kalven Report does recognise “exceptional instances” when “the university’s financial entanglements ‘may appear so incompatible with paramount social values as to require careful assessment of the consequences’,” the DisO notes that as far as the University administration is concerned, even apartheid and genocide apparently don’t qualify as “incompatible with paramount social values.”

This notion, that the purity of academic pursuits is somehow sullied by social and/or political engagement is pernicious within the academy. Further, the ethic presented in the Kalven Report informs the response of most university administrations to social and political upheavals both inside and outside its hallowed halls.

The DisO asks: “Whose priorities should our university value, and whose concerns does it actually prioritise?” From the unrest on educational campuses today (most recently at Jamia Millia Islamia Central University in Delhi, the Army Institute of Law in Mohali, the University of Hyderabad, and the Mahatma Gandhi International Hindi University in Wardha), we gather that this question, in one form or another, is being asked by students across the country. It goes on, arguing that the values prioritised by the university administration chooses “violence in place of healing and growth, punitive instead of restorative justice, and properties, assets, and prestige instead of living, breathing human beings. It is a set of priorities that should not exist at an educational institution.”

If educational institutions are to reflect a set of priorities that include growth, restorative justice, and the mental and physical health of its students and faculty, it is imperative that we periodically jog institutional memory. Student movements, in addition to their continued and principled agitations, must make attempts to ensure the “passage of intergenerational knowledge” in much the same way that the DisO so wonderfully does.

The agitations in Jamia Millia, for example, already exhibit a commendable internationalism. All that remains is for these struggles to be documented, assiduously and in good faith, and widely disseminated.

Malhar Dandekar is an independent researcher and activist based in Bangalore, India.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER