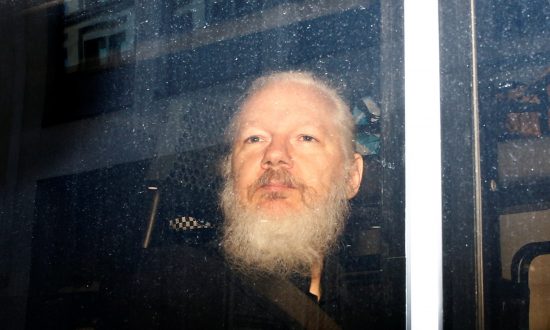

While Australian journalists bonded and broke break in condemning national security legislation that some of them had previously supported, one figure was barely mentioned. Julian Assange was making his first public appearance since April for a case management hearing at the Westminster Magistrates Court.

Those in attendance were disturbed. Craig Murray professed to being shaken. “Every decision was railroaded through over scarcely heard arguments and objections of Assange’s legal team, by a magistrate who barely pretended to be listening.” His condition had deteriorated: receding hair, premature ageing, lost weight. Some cognitive impairment seemed to have set in: incoherent trains of thought, a trouble to articulate and recall events.

By the end of the session, we were left with a few points of consideration. The first, as ever, remains that British justice is, at best, a ceremonial cloak that continues to operate in the shadows of power. Observe formalities, but do away with the substantive matters.

The second is an unfolding international dimension that links private security firms, the US intelligence services, and Ecuador in what can only be described as a political effort to eliminate a one of the most recognisable figures of publishing in recent memory. He must be done away with, mentally and physically eroded as person and being. Spiritually, he must be snuffed out.

With odds firmly against him, Assange’s defence team were keen to impress district magistrate Vanessa Baraitser on two grounds: that they be granted a preliminary hearing on the issue of whether the extradition might fall foul of the US-UK Extradition Treaty of 2003; and that they be granted a postponement of the February 24, 2020 full extradition hearing.

The latter point was based on two grounds: Assange’s acute legal isolation in Belmarsh prison and emerging evidence arising from a Spanish investigation currently underway into a surveillance operation on Assange when resident in the Ecuadorean embassy in London. The material gathered there might prove critical to the defence, not least of all its evident illegality.

When Assange was asked by the magistrate whether he had understood what had transpired, he gave the sort of reply that one would justifiably expect from a bruised, ailing political prisoner. “I don’t understand how this is equitable. This superpower had 10 years to prepare for this case and I can’t access my writings. It’s very difficult where I am to do anything but these people have unlimited resources… They are saying journalists and whistleblowers are enemies of the people. They have unfair advantages dealing with documents. They [know] the interior of my life with my psychologist. They steal my children’s DNA. This is not equitable what is happening here.

Magistrate Baraitser was not exactly feeling generous, though she did relent in granting a two months extension to Assange’s defence team, ostensibly to give them time to consult evidence emerging from Spanish investigative proceedings.

The Spanish angle on this is critical, concerning, in the words of the WikiLeaks press release, “clandestine operations against Assange, his lawyers and doctors and Assange’s family, including at the Ecuadorean embassy.” These centre on the conduct of David Morales, owner of UC Global SL, a Spanish security company charged with protecting the Ecuadorean embassy in London when Assange was its famous tenant.

Morales is being investigated by the Audiencia Nacional, Spain’s High Court, for allegedly ordering the surveillance of Assange’s conversations in the embassy, including those with his lawyers, and passing on material to US intelligence services. Morales, keen on being as comprehensive as possible in this endeavour, specifically requested his team to list “the Russian and American citizens” visiting Assange, material of which was sent to a File Transfer Protocol server in the company’s mother ship location in Jerez de la Frontera. The storage material there comprises data from phones, details on professions, and matters of nationality. Rather damnably, employees who worked for Morales’ company have revealed that the Central Intelligence Agency had access to the server.

The case being presented against Morales is a true cocktail of breaches: privacy violations, the violation of lawyer-client privilege, bribery, misappropriation, money laundering, and the criminal possession of weapons.

Morales was arrested in Jerez de la Frontera on September 17, but as the investigation is under seal, relevant material had not surfaced till this month. That said, the rather seedy resume of UC Global SL was already common knowledge, with an investigation by El País revealing the existence of a surveillance apparatus created by the company with the specific purpose of targeting Assange.

While Baraitser permitted the defence extra time to incorporate material arising from these revelations, she refused to postpone the date set for the full extradition hearing, scheduled for February 24, 2020. The matter will, however, be revisited during the December 19 case management hearing.

What the magistrate did not discuss was the evident intransigence of British authorities who have frustrated efforts by the investigating Spanish Judge José de la Mata to question Assange. On September 25, the judge sent a European Investigation Order (EIO) requesting a videoconference with Assange, who would be a witness in the case against UC Global SL. The EIO process, which came into force in Spain in 2018, is designed to ease the laborious processes behind the customary transfer of evidentiary material from one EU state to another. But the United Kingdom Central Authority (UKCA) has decided to stonewall the application, claiming that “these types of interview are only done by the police” in the UK. Nor was the request by De la Mata clear, either in grounds or on the assertion of jurisdiction.

Baffled, De la Mata has pressed the issue in determined fashion, citing previous examples of international cooperation treaties, and noting that restrictions on videoconferencing only apply to the accused, not a witness. “We also provided a clear context for our case, describing all the events and crimes under investigation.” On jurisdiction, the matter was also clear: the suspect was Spanish, the victim (Assange) had filed a complaint and the crimes in question (unlawful disclosure of secrets and bribery) were also crimes in the UK. Quod erat demonstrandum.

The district magistrate also cold shouldered hearing preliminary arguments as to whether the extradition request was barred by the 2003 US-UK Extradition Treaty. Lawyers representing Assange noted in their court submission that the Extradition Treaty “was at the time contentious, reducing the number of safeguards that might prevent extradition, in particular safeguards from the UK to the US.” Despite much weakening on the subject of citizen protections, one section in the treaty remains unaltered. Article 4(1), retained in the 2007 ratified version, makes the point that, “Extradition shall not be granted if the offence for which extradition is requested is a political offence.”

The US prosecution is positively larded with political implications. Each of the 18 charges against Assange has, at its core, an allegation of intent, namely to obtain or disclose US state secrets in such a way as to damage the security of the United States. Given that state of affairs, the defence sought to advance three grounds: that the court had jurisdiction to determine the issue of whether the charges were political in nature; that the court rule that the offences were such, pursuant to Article 4 of the Extradition Treaty, and “for that reason alone, extradition should be refused in the case.” The magistrate was not so obliging, either in listening to the grounds or giving reasons for her refusal.

Back in Assange’s home country, the editors of News Corp, Fairfax, the ABC, SBS and The Guardian, held hands in their damning campaign dubbed “The Right to Know”. Death to cultures of secrecy, they proclaimed. Onwards transparency warriors. But as with much in journalism, it is slanted, specific and skewed, ignorant of some of the most far reaching changes in the industry in the last decade. Assange remains indigestible to their sensitive palettes. Should he be extradited and convicted, their campaign will come to naught, a mere sliver of after-the-fact protest.

Perhaps fittingly, Australia has produced two notorious figures associated with journalism. They lie at two extremes of the information spectrum: Rupert Murdoch (yes, the same man behind News Corp), who continues to traffic in tits-and-bum titillation and demagoguery, influencing elections through such organs of demerit as The Sun; and Assange, who prefers revealing official secrets through WikiLeaks and, his accusers sneer, influencing elections.

At least some Australian politicians have taken the very public step of not only supporting Assange, but suggesting he return to Australia. It took some time, but this cross-party group have realised that behind the Imperium’s quest to punish the human face of WikiLeaks is a political purpose marked by the ugly, ghastly visage of the national security state.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER