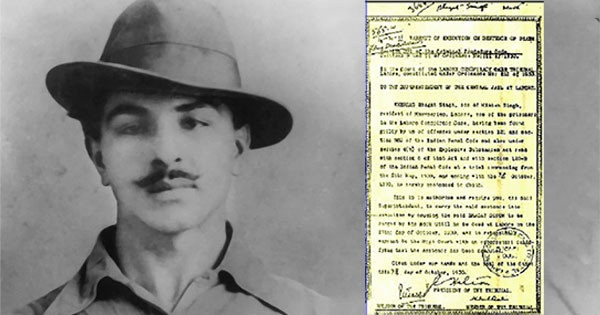

“We are next to none in our love for humanity. Far from having any malice against any individual, we hold human life sacred beyond words. We are neither perpetrators of dastardly outrages, nor, therefore, a disgrace to the country […]” This was the statement by Bhagat Singh and B K Dutta in the sessions court, Delhi, on June 6, 1929. Asaf Ali read out the statement in the court on behalf of the revolutionaries facing trial.

The statement clarifies the revolutionaries’ position further as they said:

“We humbly claim to be no more than serious students of the history and conditions of our country and her aspirations. We despise hypocrisy, our practical protest was against the institution, which since its birth, has eminently helped to display not only its worthlessness but its far-reaching power for mischief.”

The revolutionaries were emphatic in making their position – love for humanity, no malice against any individual, human life sacred, not perpetrator of dastardly outrages, despise hypocrisy, protest against the institution with its far-reaching power for mischief. This statement, although known to all, needs reiteration. The need for reiteration of this position arises as to a section of today’s political activists, human life bears no value, rather, sectarian ideology values; as this section throws away humanity while practicing ideology and politics. Dastardly outrages are part of political activism of this section; and hypocrisy is one of the tools this section uses in propagating and practicing its ideology and politics. This section doesn’t aim at institutions organized and kept active to torment humanity, torture people, loot people’s resources, exploit labor, and perpetuate exploiters’ rule, which ultimately keeps the system of exploitation intact. To this section, practicing lie is their morality, as this section doesn’t look at exploitation, which uses lies to fool the exploited. Nevertheless, no noble, from class point of view, cause, no ideology and politics of people, no political movement of the exploited is possible to organize on lies and hypocrisy, by sparing institutions of exploitations, by ignoring the question of exploitation – appropriation of surplus labor. This is the reason that makes Bhagat and Dutta’s statement immemorial in history.

The statement is considered as, Professor Chaman Lal writes in his The Bhagat Singh Reader (HarperCollins Publishers India, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, 2019; henceforth Reader) one of the “classical political documents” of this subcontinent. He also considers it as one of the “most significant political statement from the Indian revolution and revolutionaries.”

However, this should be mentioned that the statement refers to ideals of many political figures including Shivaji, Kamal Pash and Lenin as equivalent; although that is not in reality. Lenin had proletarian class point of view, which is absent in some other cases. The reference to the ideals, it’s understood, was from the standpoint of spirit – attitude for defiance, struggle, and challenge – in broader terms, perhaps, and not from specific political point of view.

The revolutionaries made another statement. Both of the two statements are considered as classic political documents from this subcontinent. These documents are essential to understand the development of political thought and political struggle in this vast land spanning from the Khyber to Kohima, Manipur. These are important documents in anti-imperialist struggle, and in the struggle for liberation of the people in this wide land; because, (1) imperialism has yet to be pushed back from this land rich with resources and with strategic position, and, (2) people are not liberated from exploitation. Black sahibs have replaced white sahibs, only. In cases, situation in areas of socio-economy and politics has deteriorated if compared to a number of aspects between the two – colonial and neo-colonial – periods. The fundamental contradictions are broadly the same: between the exploited and the exploiters, between imperialism and the people.

A number of political forces ignore these contradictions as these forces don’t find contradiction in life, in society. The reason behind their failure: Identifying contradiction in life, and consequently, in economy and politics, in areas of interests. A few don’t admit the contradictions because of their ideology, which in ultimate analysis doesn’t stand for the exploited. Moreover, a part of today’s “staunchest” fighters are “fiercely” against one brand of reactionaries, one colored backward-looking forces, one type of repression; but they feel shy to look at the entire question of the exploitation and dispossession. They are scared to question the entire system of exploitation. They forget to search the root of all repression against all the exploited irrespective of color, caste and creed; and they, thus, join hands with another brand of reactionaries, with another color of sectarian and supremacist roaders, with another faction of imperialists, and, at times, shamefully, with intelligence agencies donning another cloak. Nevertheless, the crude “clever tact” gradually is exposed to political activists aware of basic questions related to contradictions in a society. That’s the reason these “fierce fighters” don’t look at the contradiction-question, but shout with questions of repressions to a single sect – an act of betrayal to the exploited people.

From this point, the documents are not only classic, but also essential learning material for today’s learners of class politics. And, here, Professor Chaman Lal has done the splendid work – present the political documents. The Reader, thus, appears an essential book for political scientists and political activists/learners.

Bhagat Singh’s call is still relevant if one looks at the reality gripped by exploitation in this land. In one of his political letters, documented in the Reader, the revolutionary writes:

“The youth will have to spread [the] revolutionary message to the far corner of the country. They have to awaken crores [10 million=1 crore] of slum-dwellers of the industrial areas and villagers living in worn-out cottages, so that we will be independent and the exploitation of man by man will become impossibility.” (Message to the Punjab students’ conference, October 19, 1929, p. 65-66)

The message was read out in the conference, chaired by Netaji Subhas Bose – a powerful political position – held on October 19, 1929 in Lahore; and it was published in the Tribune on October 22, 1929.

The message, addressed to “Comrades”, begins by telling about a significant political path – renounce adventurism. The first sentence says: “Today, we cannot ask the youth to take to pistols and bombs. Today, students are confronted with a far more important assignment. In the coming Lahore Session the Congress is to give call for a fierce fight for the independence of the country. The youth will have to bear a great burden in this difficult time in the history of the nation.” (ibid.)

The proposals – to the youth, to the Congress – reflect the reality of that time: The youth were the vanguard in political fight, or, the youth were considered in that way; and, it was the Congress that was considered as the main conveyer of the call to independence. Readers of the history of political fights, factional fights, within the Congress at different phases of the political organization are aware of the factional fights and the parties entangled in those fights. The organizers of the struggle for an exploitation-free society had to confront that reality – either make a compromise with the reality, or, ignore the reality, or, handle the contradiction-filled reality in a correct way; and all of these were tactical questions.

Bhagat Singh’s last letter written to his comrades on March 22, 1931 tells the high moral ground, sense of dignity, allegiance and duties to the people, and the revolutionary spirit he held. The revolutionary, without any hypocrisy, writes:

“It is natural that the desire to live should be in me as well, I don’t want to hide it. But I can stay alive on one condition that I don’t wish to live in imprisonment or with any binding.

“My name has become a symbol of Hindustani revolution, and the ideals and sacrifices of the revolutionary party have lifted me very high – so high that I can certainly not be higher in the condition of being alive.

“Today my weaknesses are not visible to the people. If I escape the noose, they will become evident and the symbol of revolution will be tarnished, or possible obliterated. But to go to the gallows with courage will make Hindustani mothers aspire to have children who are like Bhagat Singh and the number of those who will sacrifice their lives for the country will go up so much that it will not be possible for imperialistic powers or all the demoniac powers to contain the revolution.

“And yes, one thought occurs to me even today – that I have not been able to fulfill even one thousandth parts of the aspirations that were in my heart to do something for my country and humanity. If I could have stayed alive and free, then I may have got the opportunity to accomplish those and I would have fulfilled my desires. Apart from this, no temptation to escape the noose has ever come to me. Who can be more fortunate than me? These days, I feel very proud of myself. Now I await the final test with great eagerness. I pray that it should draw closer.”

He concluded the letter by writing:

“Your comrade

“Bhagat Singh”

The letter tells about a revolutionary, about the attitude and feeling to life, people and country revolutionaries should have. It’s a lesson to all revolutionaries, to all aspiring to serve people. And, it’s not only of that period; it’s of all periods in societies struggling for radical change, for totally altering exploiter-exploited equation – make all the exploited free from all forms of shackles. The shackles are not only of economic and political exploitation, but also of indignity and dishonor.

Bhagat Singh’s letter to B K Dutt from Central Jail in November 1930 is an example of the revolutionary’s idea and ideal:

“The judgement has been delivered. I am condemned to death. In these cells, besides myself, there are many other prisoners who are waiting to be hanged. The only prayer of these people is that somehow or other they may escape the noose. Perhaps I am the only man amongst them who is anxiously waiting for the day when I will be fortunate enough to embrace the gallows for my ideal.

“I will climb the gallows gladly and show to the world as to how bravely the revolutionaries can sacrifice themselves for the cause.

“I am condemned to death, but you are sentenced to transportation for life. You will live and, while living, you will have to show to the world that the revolutionaries not only die for their ideals but can face every calamity. Death should not be a means to escape the worldly difficulties. Those revolutionaries who have by chance escaped the gallows for the ideal but also bear the worst type of tortures in the dark dingy prison cells.”

These utterances reflect the revolutionary’s attitude to life, ideal and duty. The revolutionary, like his many comrades, was steeled in the fire of revolution.

Their struggle inside prison was exemplary, also. Bhagat Singh and his comrades, Chaman Lal writes in the Reader, carried on hunger strike for 110 days, which they began on June 15, 1929 demanding status of Political Prisoner. Jatindra Nath Das, Bhagat Singh’s comrade, died on September 13, after 63 days of hunger strike. The hunger strike was halted on October 4, 1929 after concrete assurance from the colonial British government and Congress leaders. But, the British government officials not only dishonored the commitment they made, but resorted to oppressing the revolutionaries in jail, and even in court. Bhagat Singh and many were injured after they were badly beaten by police between October 21-24 in court and in jail. That was imperialist civility and rule of law!

On February 14, 1930, hunger strike was again initiated to realize all the demands. This hunger strike was of two weeks.

These struggles are noteworthy not only in the context of this sub-continent, but also in the context of all other countries.

The Reader presents many important political documents – works of Bhagat Singh – necessary for learners of people’s politics. A number of the works point out the position proletarians should proclaim. The manifesto of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) declares:

“Revolution is a phenomenon which nature loves and without which there can be no progress either in nature or human affairs.”

It characterized the Indian capital of that time:

“Indian capital is preparing to betray the masses into the hands of foreign capitalism and receive, as a price of this betrayal, a little share of government of the country.”

The manifesto, then, presented a path:

“The hope of the proletariat is, therefore, now centered on socialism, which alone can lead to the establishment of complete independence and the removal of all social distinction and privileges.”

It called upon the youth:

“Sow the seeds of disgust and hatred against British imperialism […]”

The political document, at its conclusion, declared:

“The sovereignty of the proletariat […]”

The document is an example of the ideological position, orientation and worldview the HSRA held: For the exploited, for a society free from exploitation, oppose all exploiters including imperialism.

Chaman Lal writes in the Reader: “Two documents – the manifestos of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha (NBS) and the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) – are the most important ideological texts to understand Bhagat Singh and his comrades’ struggle for Indian freedom from British colonialism. The drafts of both were written by Bhagwati Charan Vohra, with Bhagat Singh being consulted before they were finalized for publication.”

Studying Bhagat Singh is essential for the study of politics, both of the people and of the ruling elites, in this subcontinent. The Reader helps this study by presenting a lot of basic documents. Its appendices, if someone ignores rest of the volume, presents many facts documents and information required primarily for study of Bhagat Singh. The Reader, in its 616 pages, bears the hard labor Professor Chaman Lal has put to present Bhagat Singh. And, Bhagat Singh is neither a single revolutionary nor representing a single revolutionary organization oriented to proletarian ideal. Bhagat Singh represented a people’s revolutionary aspiration, dream and political struggle in a historical period. The Reader, thus, is an important resource material to begin study of that struggle in that period, which is required for study of the present.

Note: This is the 3rd/concluding part of a series introducing The Bhagat Singh Reader by Professor Chaman Lal. The 1st and 2nd parts appeared in Countercurrents, India, Frontier, Kolkata, India, and New Age, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Farooque Chowdhury writes from Dhaka.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER