The Arctic is increasingly at risk as temperatures warm and sea ice melts away, warns U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in its Arctic Report Card (ARC), an annual report on the state of this crucial ecosystem.

Climate crisis is causing chaos in the Bering Sea, home to one of America’s largest fisheries, said the U.S. federal government agency’s scientists in the 2019 ARC on Tuesday. The Bering Sea chaos is an example of how rising temperatures can rapidly change ecosystems important to the U.S. economy.

Scientists said warming in the Arctic, which functions as a global air conditioner, could lead to rapid changes far away from the region.

Rising temperatures in the Arctic have led to decreases in sea ice, record warm temperatures at the bottom of the Bering Sea and the northward migration of fish species such as Pacific cod, said the ARC.

While the changes are widespread in the Arctic, the effect on wildlife is acute in the eastern shelf of the Bering Sea, which yields more than 40% of the annual U.S. fish and shellfish catch.

The warning was the latest from a U.S. government agency about climate crisis even as U.S. President Donald Trump has voiced skepticism about global warming and pushed to maximize production of oil, gas and coal. Last month the Trump administration filed paperwork to withdraw the U.S. from the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change.

The report identified a decrease in recent years in the Bering Sea “cold pool,” which used to be a dependable mass of very salty frigid water down to the sea floor that functioned as a natural fence separating fish species. That has likely caused a shift in distribution of walleye Pollock and Pacific cod, the report said.

No cold pool was found in 2018 and this year it was smaller than normal, it said.

Fish stocks are scrambled, with some species moving north. Crab fishermen in Nome have reported catching more cod than crabs, as Pacific cod are not doing as well south of there.

Last week, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council shut down the 2020 Pacific cod harvest in the Gulf of Alaska.

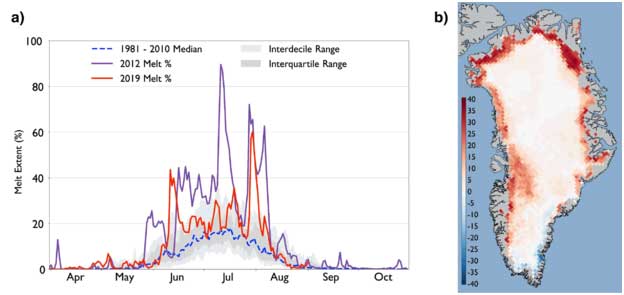

The report also said the melt of the ice sheet over Greenland this year rivaled that of 2012, the previous year of record ice loss.

It also detailed a shift of Arctic permafrost regions from being a sink for carbon dioxide emissions to a source of them, as warming uncovers soil, triggering microbes to emit the main gas linked to global warming.

The wide ecosystem changes also affect the 70 communities of indigenous people in the Bering Sea, with hunters seeking seals, walrus, whales and fish having to travel much farther offshore as the ice melts.

According to the ARC, the Arctic has experienced its second warmest year since 1900, raising fears over low summer sea ice and rising sea levels.

The North Pole has been warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet since the 1990s, a phenomenon climatologists call Arctic amplification, and the past six years have been the region’s warmest ever.

The average temperature in the 12 months to September was 1.9 degrees Celsius higher than the 1981-2010 average, according to the ARC.

The end-of-summer sea ice cover measured that month was the second lowest in the 41-year satellite record, tied with 2007 and 2016, the report said.

“It’s heartbreaking,” said Simon Kinneen, the chairperson of the North Pacific Fishery Management Council.

Cod stocks have been hard hit by successive heat waves in the Gulf of Alaska, fishery scientists say.

“Our hunters are finding it more difficult to navigate on the land and are moving out to sea,” Mellisa Johnson, the executive director of the Bering Sea Elders, told a meeting in San Francisco of the American Geophysical Union, where the report was released.

“The changes going on have the potential to influence the kinds of fish products you have available to you, whether that’s fish sticks in the grocery store or shellfish at a restaurant,” said Rick Thoman, a meteorologist in Alaska and one of the report’s authors.

“Two years ago nobody was talking about a wholesale shift in the Bering Sea ecosystem,” Thoman said.

“2007 was a watershed year,” Don Perovich, a Dartmouth engineering professor who co-authored the report, told AFP.

“Some years there’s an increase, some years there’s a decrease, but we’ve never returned to the levels we saw before 2007,” he added.

The year up to September has been surpassed only by the equivalent period in 2015-16 – the warmest since 1900, when records began.

In the Bering Sea between Russia and Alaska, the last two winters have seen maximum sea ice coverage of less than half the long-term average.

The ice is also thinner, meaning airplanes can no longer land with supplies for the residents of Diomede, a small island in the Bering Strait, who now depend on less reliable helicopters.

Thick ice is also vital for locals who travel by snowmobile and stow their boats, or hunt seals and whales.

As the ice forms later in the fall, the inhabitants are isolated for a greater part of the year.

The “shorefast ice,” anchored to the sea floor, is increasingly rare, and it is on this ice that fishermen and hunters store their equipment.

“In the northern Bering Sea, sea ice used to be present with us for eight months a year. Today, we may only see three or four months with ice,” indigenous residents wrote in an essay included in the ARC.

“We are seeing coastal landslides, large sinkholes and methane bubbling up through our ponds in summer,” the indigenous authors write. It’s that last part, methane release, or greenhouse gases in general, that extends far beyond the Arctic.

That’s because permafrost soils, composed partially of carbon-rich organic matter, contain at least two times the amount of carbon than there is currently in the atmosphere. Because of warming, permafrost is no longer a net sink for carbon; it has become a net emitter of heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

The ARC makes clear that what happens in the Arctic will not stay in the Arctic — the changes reverberate all around the world and will only accelerate as the globe continues to heat. But the ones most at risk right now are the indigenous people who count on knowledge passed through the generations.

“The world from our childhood is no longer here. Our young children today are seeing so much change, but it is difficult for them to understand the pace. We are losing so much of our culture and connections to the resources from our ocean and lands,” they write.

Dr. Ted Schuur is the author of the permafrost section of the report. He says these emission signals are “kind of like a ‘canary in a coal mine’ telling us that permafrost ecosystems are out of historical balance, and are starting to cause climate change to happen faster.” This is yet another feedback, which accelerates Arctic amplification.

Greenland ice losses rising faster than expected

That acceleration is vividly illustrated by melting water cascading into the ocean from Greenland.

According to another study released Tuesday, Greenland is shedding ice seven times faster than in the 1990s. This pace is on the high end of the warming scenarios laid out by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). As a result, the study estimates that 40 million more people worldwide will be exposed to coastal flooding by 2100, for a total of 400 million.

Greenland ice melt in 2019 (in red), compared to the record year of 2012 (in purple). NOAA

It is not just sea ice that is receding, according to the report: ice on Greenland is also melting.

For the rest of the world this melt is measured by rising sea levels. Each year ice melting from Greenland alone raises global sea levels by 0.7 millimeters.

The snow reflects the sun’s rays back to space, but when it melts, it uncovers more area for the sun’s heat to be absorbed and melts the permafrost, the soil that remains constantly frozen.

Greenland has the world’s second largest ice sheet after Antarctica, which is melting at a slower pace. Scientists noted Tuesday that Greenland is struggling too, however.

It has lost 3.8 trillion tonnes of ice since 1992, enough on its own to add 10.6 millimeters (1.06 centimeters, 0.4 inches) to sea levels, according to a study report – “Mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet from 1992-2018” – by the Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise (IMBIE) team in the journal Nature on December 10, 2019

If all of Greenland’s ice melted, or were diverted into the ocean as icebergs, the world’s oceans would rise by 7.4 meters, scientists say.

A team of 96 polar scientists from 50 international organizations has produced the most complete picture of Greenland ice loss to date. The IMBIE team combined 26 separate surveys to compute changes in the mass of Greenland’s ice sheet between 1992 and 2018. Altogether, data from 11 different satellite missions were used, including measurements of the ice sheet’s changing volume, flow and gravity.

The findings show that the rate of ice loss has risen from 33 billion tonnes per year in the 1990s to 254 billion tonnes per year in the last decade, which is a seven-fold increase within three decades.

The assessment, led by Professor Andrew Shepherd at the University of Leeds and Dr Erik Ivins at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, was supported by the European Space Agency (ESA) and the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

In 2013, the IPCC predicted that global sea levels would rise by 60 centimeters by 2100, putting 360 million people at risk of annual coastal flooding.

Professor Shepherd said: “As a rule of thumb, for every centimeter rise in global sea level another six million people are exposed to coastal flooding around the planet.” “These are not unlikely events or small impacts; they are happening and will be devastating for coastal communities.”

The team also used regional climate models to show that half of the ice losses were due to surface melting as air temperatures have risen. The other half has been due to increased glacier flow, triggered by rising ocean temperatures.

Ice losses peaked at 335 billion tonnes per year in 2011 – ten times the rate of the 1990s – during a period of intense surface melting. Although the rate of ice loss dropped to an average 238 billion tonnes per year since then, this remains seven times higher and does not include all of 2019, which could set a new high due to widespread summer melting.

It should be mentioned that 360 billion tonnes of ice is roughly equivalent to 1 millimeter of global sea level rise.

Dr Ivins said: “Satellite observations of polar ice are essential for monitoring and predicting how climate change could affect ice losses and sea level rise.”

“While computer simulation allows us to make projections from climate change scenarios, the satellite measurements provide prima facie, rather irrefutable, evidence.”

“Our project is a great example of the importance of international collaboration to tackle problems that are global in scale.”

Guðfinna Aðalgeirsdóttir, Professor of Glaciology at the University of Iceland and lead author of the IPCC’s sixth assessment report, who was not involved in the study, said: “The IMBIE Team’s reconciled estimate of Greenland ice loss is timely for the IPCC. Their satellite observations show that both melting and ice discharge from Greenland have increased since observations started.”

“The ice caps in Iceland had similar reduction in ice loss in the last two years of their record, but this last summer was very warm here and resulted in higher loss. I would expect a similar increase in Greenland mass loss for 2019.”

“It is very important to keep monitoring the big ice sheets to know how much they raise sea level every year.”

Satellite missions providing data

The satellite missions providing data for this study are European Space Agency’s ERS-1, ERS-2, Envisat, and CryoSat-2, the European Union’s Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency Advanced Land Observatory System; the Canadian Space Agency RADARSAT-1 and RADARSAT-2; the NASA Ice, Cloud, and land Elevation Satellite; the NASA / German Aerospace Center Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment; the Italian Space Agency COSMO-SkyMed, and the German Aerospace Center TerraSAR-X.

Arctic Report Card: Update for 2019

Arctic ecosystems and communities are increasingly at risk due to continued warming and declining sea ice

Highlights of the ARC report

- The average annual land surface air temperature north of 60° N for October 2018-August 2019 was the second warmest since 1900. The warming air temperatures are driving changes in the Arctic environment that affect ecosystems and communities on a regional and global scale.

On the land

- The Greenland Ice Sheet is losing nearly 267 billion metric tons of ice per year and currently contributing to global average sea-level rise at a rate of about 0.7 mm yr.

- North American Arctic snow cover in May 2019 was the fifth lowest in 53 years of record. June snow cover was the third lowest.

- Tundra greening continues to increase in the Arctic, particularly on the North Slope of Alaska, mainland Canada, and the Russian Far East.

- Thawing permafrost throughout the Arctic could be releasing an estimated 300-600 million tons of net carbon per year to the atmosphere.

In the oceans

- Arctic sea ice extent at the end of summer 2019 was tied with 2007 and 2016 as the second lowest since satellite observations began in 1979. The thickness of the sea ice has also decreased, resulting in an ice cover that is more vulnerable to warming air and ocean temperatures.

- August mean sea surface temperatures in 2019 were 1-7°C warmer than the 1982-2010 August mean in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas, the Laptev Sea, and Baffin Bay.

- Satellite estimates showed ocean primary productivity in the Arctic was higher than the long-term average for seven of nine regions, with the Barents Sea and North Atlantic the only regions showing lower than average values.

- Wildlife populations are showing signs of stress. For example, the breeding population of the ivory gull in the Canadian Arctic has declined by 70% since the 1980s.

Focus on the Bering Sea

- The winter sea ice extent in 2019 narrowly missed surpassing the record low set in 2018, leading to record-breaking warm ocean temperatures in 2019 on the southern shelf. Bottom temperatures on the northern Bering shelf exceeded 4°C for the first time in November 2018.

- Bering and Barents Seas fisheries have experienced a northerly shift in the distribution of subarctic and Arctic fish species, linked to the loss of sea ice and changes in bottom water temperature.

- Indigenous Elders from Bering Sea communities note that “[i]n a warming Arctic, access to our subsistence foods is shrinking and becoming more hazardous to hunt and fish. At the same time, thawing permafrost and more frequent and higher storm surges increasingly threaten our homes, schools, airports, and utilities.”

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER