In the days of yore, Savitri saved Satyavan

The legend of Savitri and Satyavan in the Hindu mythological epic, the Mahabharat, is a love story. Savitri, a beautiful princess, marries Satyavan, a penniless woodcutter, despite Sage Narada warning her that Satyavan, is a dead man walking. A year later, on the day of reckoning, Yama, the God of death, comes to collect Satyavan’s soul. Savitri pleads with Yama to take her too, but Yama declines. Yama, touched by Savitiri’s love for Satyavan, grants her a boon. Savitri asks for children, which Yama grants. He then realizes the implication of his boon and gives Satyavan his life back so that he and Savitri can have children.

Savitri pleads with Yama for her husband’s life, Satya.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London

The Savitri-Satyavan story is being played out in real life in the ongoing climate change saga. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), playing the role of Narada, has issued a strong warning of the possible demise of the earth (read Satyvan) as we know it today. UNEP has just published the “Emissions Gap Report 2019” (EGR2019). The report states, “We are on the brink of missing the opportunity to limit global warming to 1.5°C.”

Scientists warn that a warming exceeding 1.5oC above pre-industrial times would result in catastrophic consequences—rapid glacier melt, rising sea levels, acidifying oceans, greater rainfall and temperature unpredictability, frequent extreme weather events, rise in species extinction rates, decrease in food and water security and consequent rise in malnutrition and disease.

The EGR is published annually every November just before the inter-governmental body, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), meets to decide the future course of global action to tackle climate change. The EGR makes an assessment of the gap between greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions today and what they should be for us to remain within 1.5oC temperature rise redline.

UNEP also recently published another report, “Lessons from a Decade of Emissions Gap Assessment” (EGR10). The EGR10 compares the emission gap predictions it made 10 years ago with today’s, and concludes that “Despite a decade of increasing political and societal focus on climate change and the milestone Paris Agreement, the global GHG emissions have not been curbed, and the emissions gap is larger than ever.”

The writing on the wall is clear—climate change poses a clear and present danger. Together both reports tell us that the yawning gap between climate science and climate policy has never been wider, and that to avoid descending into an apocalypse, drastic corrective measures must be taken immediately.

Two decades of global climate agreements …. and we are still highly unsustainable

Inter-governmental cooperation to tackle climate change began in 1997, when the Kyoto Protocol (KP) was drafted. The KP granted preferential emission rights to 42 North nations, but obliged them to reduce their collective emissions by 5.2% by 2012 over the base year 1990 (the KP period). In 2013, the emission reduction of North nations for the KP period was estimated at 16%, and the KP was hailed as a “runaway success.” The KP did not bind the South nations with any emission reduction targets.

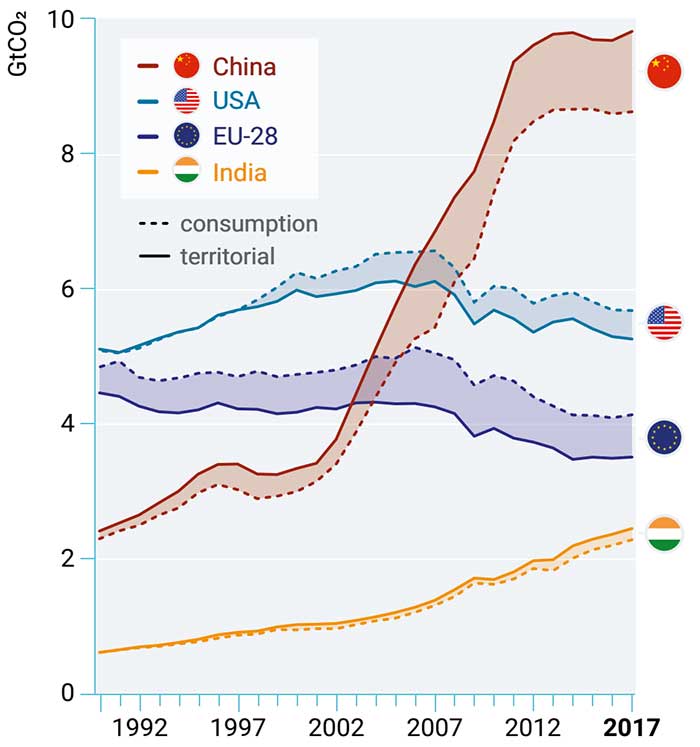

The KP required computation of territorial emissions, i.e., all GHG emissions emitted from a territory were attributed to that country. This is at variance with consumption emissions of a territory, which is the true reflector of the emissions of a territory. To compute consumption emission, embedded carbon emissions of imports are added, and those of exports are subtracted (net trade emissions) to territorial emissions.

Consumption emissions of North nations for the KP period increased by 14.5%, which questions the validity of the 16% emission reduction computed by the territorial emissions method. Outsourcing of goods and services consumed by North nations to South nations, particularly to India and China, which was in vogue by 1990, helped the North nations in two ways—reduced prices of many products and shifted the crediting of a significant amount of trade emissions from North to South nations.

Gap between territorial and consumption emissions of major GHG emitters (Source EGR2019)

Secondly, clubbing emissions of all North nations hid the real performance of their bad performers, particularly large emitters. During the KP period, the emissions of USA, Canada and Australia increased by 6% instead of decreasing by their 6% target. West European countries fared better. As against their target of an 8% emissions reduction, they reduced by 7%. During the KP period, East European and Russian emissions reduced by 55% as their economies shrank drastically after the 1990 Soviet bloc collapse. This more than compensated for the poor emission reduction performance of large emitters such as the US.

The KP was a “runaway failure.” Instead of retarding emissions growth, it transferred the crediting of consumption emissions from North to South nations, primarily China and India, and allowed the North nations to blame them for their rapid emissions growth.

KP’s successor, the Paris Agreement, drafted in 2015, aims to strengthen global response to climate change to limit warming to 2oC above pre-industrial levels and to pursue effort to limit it to 1.5oC. The agreement will also help countries adapt to climate change impacts, foster low carbon development pathways and steer global financial flows to enable these processes.

As of November 2019, 195 countries had signed the agreement. Under the agreement, each country may determine, plan, and regularly report any non-binding contribution (known as nationally determined contributions or NDC) it wishes to pledge to mitigate global warming. Each new NDC that a country pledges must be more ambitious than the previous one.

An inter-governmental meeting, known as the Conference of Parties (COP) # 25 is underway in the first fortnight of December 2019 in Madrid to take stock of the progress made by the Paris Agreement, and prepare for the next COP meeting to be held in 2020. Major course changes are expected to be attempted in COP 26, to be held in Glasgow in November 2020.

…. the gap between “what we say we will do and what we need to do” has widened

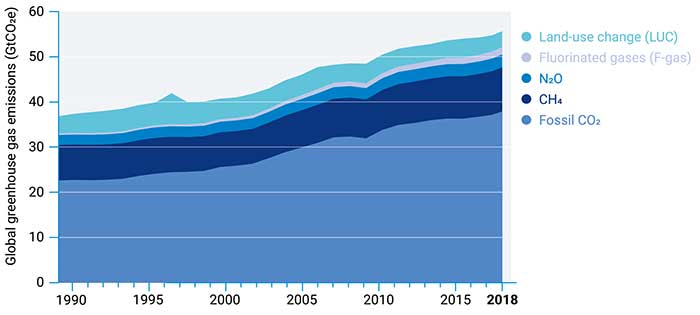

In the last decade, GHG emissions rose by 1.5% per annum, reaching a record high of 51.8 GtCO2e (without LUC), 55.3 (with LUC) in 2018. The early years of the Paris Agreement do not indicate any significant reduction in emissions growth.

Global GHG emissions from all sources (Source: EGR2019)

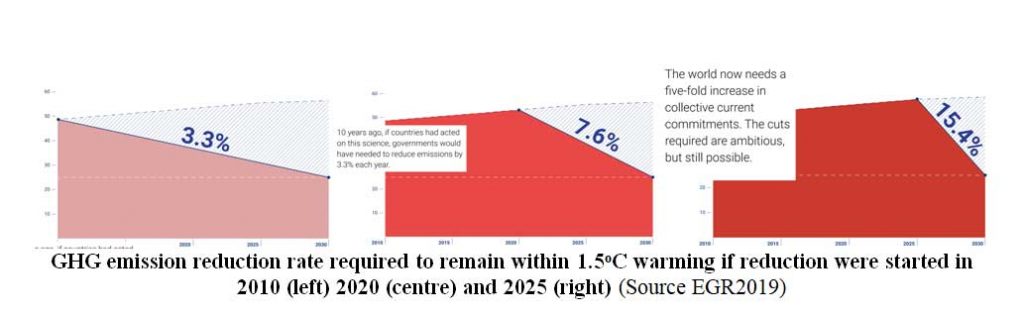

To have a fighting chance of restricting global warming to 1.5oC, the EGR2019 indicates that GHG emissions must tumble down to 25 GtCO2e by 2030, i.e., half of what it is today. If emissions reduction had begun a decade back, the reduction rate would have been a mere 3.3% per annum. If it starts today, GHG emissions must decrease by a stiff 7.6% every for the next 10 years. A 5 year delay, i.e., a 2025 start for an emissions reduction to begin will increase the GHG reduction rate climb to a virtually unattainable 15.4% per year.

To move from a GHG emission growth rate of +1.5% to -7.6% is Herculean task, a shift of 9% in one year. To do that requires all countries to have the will, wherewithal and willingness to be on the same page. This has not happened in the past. In fact, it is the reverse that has happened. The emissions gap computed in EGR2015 and EGR2018 for a 1.5oC warming almost doubled from 17 GtCO2e in 2015 to 32 GtCO2e in 2018, i.e., the Paris Agreement is failing.

For the first time UNEP has used tough language to make the COP 25 delegates and the world sit up and reflect on the business-as-usual way in which climate change happening. The EGR2019 states that, “Today our report card says we are failing to close the ‘commitment’ gap between what we say we will do and what we need to do to prevent dangerous levels of climate change.”

…. US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement makes it worse

Following up on Donald Trump’s earlier promise, in November 2019 the US announced its intention to pull out of the Paris Agreement. In the last decade US emissions, which are 13.2% of global emissions, remained constant at ~6.8 GtCO2e per annum. Assuming that that they remain flat till 2030, and other countries made deeper emissions cuts to compensate for US intransigence, they would have to reduce their GHG emissions by an almost impossible 9.5% per year till 2030. However, if US emissions creep upwards, as they did in 2018 to 3.4% per year, the biggest spike in 8 years, the other countries may not make any further cuts and the 1.5oC temperature ceiling would be busted.

There is a yawning gap between the Paris Agreement’s aim to reduce emissions and their unabated increase in GHG emissions.

Missing element in the discourse–Climate justice and development

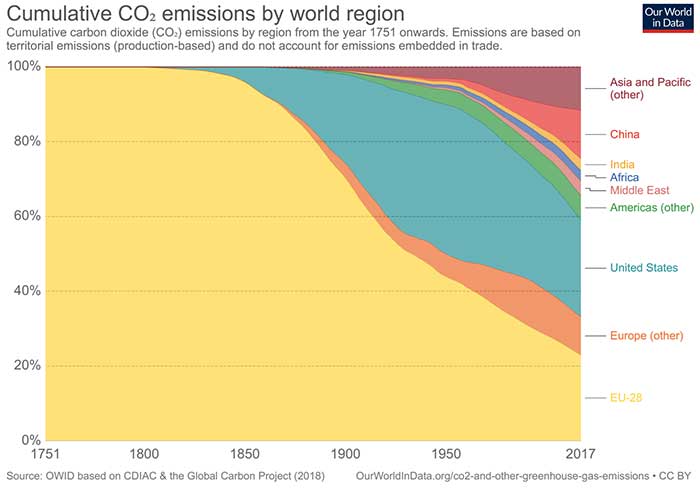

North nations (Europe, USA, Canada, Australia, Japan), with 17% of the world’s population today, are have emitting over 60% of the 2,200 GtCO2 of historic emissions (cumulative emissions 1751-2017). The per capita historic emissions of North and South nations are 1,200 and 85 t/person[2], respectively. The rich in South nations, though small in number and asset holding, also share a small fraction of the responsibility for causing climate change.

Climate justice requires that per capita historic emissions, or at least per capita current emissions, for all people of the world be more or less the same. Else, those with less per capita emissions—historic or current, will feel short changed, and will argue for increasing their emissions to catch up with the level of development of the “privileged” by burning more fossil fuels. This argument gets further lift by the considerable doubt there exists regarding renewable energy’s ability to replace fossil fuels completely.

So, what should a South nation do? Let us take the case of India. It has emitted only 3% of world’s historic emissions. With 17% of the world’s population, its current emissions are 7% of global emissions. Its per capita GHG emissions are only ~42% of the global average per capita emissions of 6.6 GtCO2e. India aspires to have its GDP grow at 8-10% per annum. Its emissions growth in the last decade was 3.7% per annum, and its emissions in 2018 grew at 5.5%. Seventy five percent of its commercial energy comes from fossil fuels. Its population below the national poverty line and multi dimensional poverty index are 29.5% and 44%, respectively.

If India allows its GHG emissions to grow, it will contribute to shooting down the 1.5oC temperature rise redline. Further growth by any of the large emitters, including India, is virtually not possible without running the risk of crossing the 1.5oC redline as the world’s remaining emissions budget for staying under 1.5°C warming is all but gone. Decreases emissions by reducing fossil fuel use implies allowing GDP growth to flag; and that condemns 30-40% of its population to remain under the poverty line as India has chosen to use the flawed trickle-down theory of development.

The North nations have forced the South nations into a Catch-22 situation where they are damned if they reduce emissions and they are damned if they do not. Moreover, South nations are far more vulnerable to climate change than North nations—because of their geography and their lower capacity to meet disasters. And India, as part of South Asia, whose historic emissions are 3.5%, is in one of two regions that will suffer the most from climate change impacts.

India will be subject to internal stresses such as extreme weather events, sea rise, floods, droughts, decreasing food and water security, internal migration. It will also be subject to external stresses as almost all of the Maldives and a quarter of Bangladesh will be under the sea by 2100. More than 5 crore Bangladeshi climate refugees may well walk into India by as early as 2050. Nepal and Bhutan will reel under frequent glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) and consequent devastating flooding. Pakistan and Afghanistan will become severely water stressed countries as their rivers are highly dependent on glacial melt, and as glaciers melt, their rivers will run dry.

…. is there a Savitri who can save the world, and India

At the current global GHG emission growth rate of 1.5% pa, the world will warm by 1.5-2oC in a few short decades. In the EGR10 and EGR2019 UNEP warns, “Unless mitigation ambition and action increase substantially and immediately, exceeding the 1.5°C goal can no longer be avoided” and “If we rely only on the current climate commitments of the Paris Agreement, temperatures can be expected to rise to 3.2°C this century.” In other words, the average temperature in future may be nearly as high as what meteorological departments currently classify as heat waves.

Recent scientific findings are noteworthy. The first is the study of Antarctica ice sheets that made scientists conclude that abrupt and irreversible changes in the climate system have become a higher risk at lower global average temperatures. The second is new evidence that climate systems separated by thousands of kilometers, e.g., the Arctic sea ice and the Amazon forests, may be inter-connected and that exceeding tipping points in one system can increase the risk of crossing them in others. The third is that new climate models being used for the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, to be released in 2021, predict that temperature rise by 2100 may be as high as 6.5-7oC. Climate change has put the earth’s environment and human society at the risk of drastic and permanent damage.

It will take time for these findings to be verified. But scientific uncertainty is no longer a good reason for procrastination, as earth, like Satyavan, has become a dead man walking. If policy makers continue to play “fiddler on the roof,” as they have till now, someone else has to play the role of Savitri and save the earth. It is only people who can do that, and save their environment and themselves. That has already started in some North nations with mass action, and must now spread to South nations.

So what should people do? They should form national rainbow coalitions of people of all walks of life—workers, farmers, fisher folk, youth, women, scientists, and link up with one another. Next they should ask national governments and the UN to declare a climate crisis and implement stringent measures immediately in the following five areas:

Sustainability: North nations emissions must become net carbon zero by 2030, and South nations by 2040. Gross global consumption should be reduced to sustainable levels and a sustainability index should be agreed upon to measure efficacy of sustainability objectives. These measures include leaving 80% of the remaining fossil fuel reserves in the ground and every nation sequestering its consumptive emissions within its territory.

Taking responsibility: All nations should take responsibility for climate change related injury, displacement and property loss to people, and damage to the environment, in proportion to their historic emissions. And within each nation, the same principle should be applied to individuals with regard to their current emissions.

Equity: By 2040, global per capita energy consumption and emissions equity should be achieved.

Governance: Decentralized and autonomous local self governing bodies of communities must have oversight powers over provincial and national governments, and international cooperation agencies. Decisions at all governance levels must be democratic and transparent.

Environmental restoration: Air, water, land, soil, and to the extent possible biodiversity, should be restored to their earlier quality.

People should also take the initiative and themselves implement such programmes that do not require government intervention or help, e.g., organic farming, dispensing with private transport, etc. After all it is the future of their children and grandchildren that is at stake.

Published in Firstpost, 13.12.2019: https://www.firstpost.com/tech/science/climate-crisis-is-there-a-savitri-to-save-the-world-from-its-climate-catastrophe-7774451.html

|

Sagar Dhara is an environmental engineer specialized in risk analysis. He had worked earlier as a consultant with UNEP, as Director, Envirotech Consultants, and faculty, BITS Pillani

[2] Per capita historic emissions are computed by dividing the historic emissions (1751-2017) of a country/region divided by the current population

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER