There has been a hurried spate of cancellations and suspensions of elections across the globe because of the risk posed by COVID-19. The trend is unsurprising. In the age of post-democratic process, suspending the procedure should only induce a cough of recognition. But it is troubling for those who take the ceremonial aspect of these things seriously. Such tendencies have worried Jon Meacham, who went to the history books to remind New York Times readers that President Abraham Lincoln, even during a murderous civil war, would still insist on having an election he could lose.

A state of emergency, in other words, need not be inconsistent with democratic practice, though Meacham conveniently sidesteps Lincoln’s tyrannical streak in suspending the writ of habeas corpus by presidential decree and his hero’s acknowledgment that the executive could “in an emergency do things on military grounds which cannot be done constitutionally by Congress.”

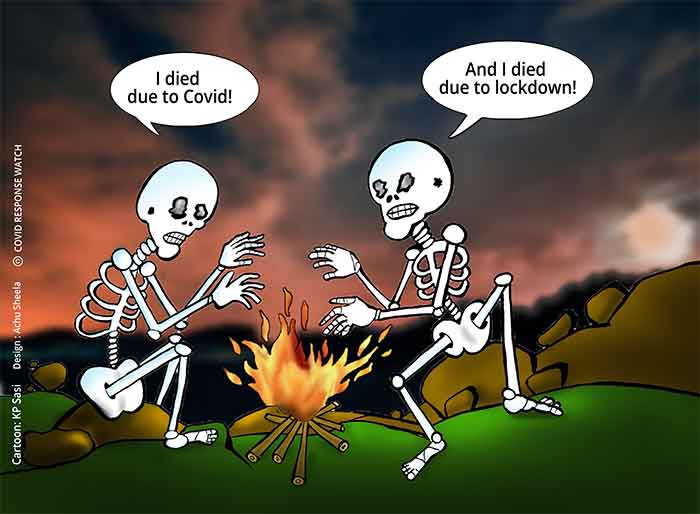

The short of it is that states of emergency are dangerous times for rights and liberties. To speak about the liberty of the subject during crisis is considered individualistic and indulgent. Put the collective and polity first and your silly notions of freedom a distant second.

States of emergency can be varied creatures. Declaring a state of emergency, writes Théo Fournier on the Italian example in responding to COVID-19, entails giving “the central government the possibility to intervene directly in the affairs of the sub-state administrations (regions, provinces, metropolitan cities and communes). The necessity of coordinated response to the crisis bypasses the principles of subsidiarity and division of competences applicable in normal times.”

Some infringements and containment of liberty may well be warranted, though the jurists warn about the need for time limits and proportionality. “Despite their severity,” comes Fournier’s assessment, “the Italian measures pass the test of a legitimate infringement.” The Italian Constitution contemplates limitations on the freedom of movement, and the measures undertaken were, for the most part, proportionate.

Pressing emergencies can furnish political opportunists with the means to fortify their positions. They seek the archive of executive justifications in times of crisis for assistance, claiming that the threat can only be extinguished with authoritarian measures. The use of the term “war” in combating infection, an erroneous formulation at best, has provided the convenient covering of an iron glove.

The German authoritarian jurist Carl Schmitt went so far as to suggest that states of emergency undercut the very idea of legal norms, repelling them as they take hold. States of abnormality demand certainty and focused responses, not vague measures heavily qualified by restraint. The only certainty that can be provided is by the unchallenged sovereign who defines what Schmitt famously called “the state of the exception”. (This leads to a classic form of circular reasoning: to be sovereign, you need to be able to define that state of the exception; to define that state, you need to be sovereign.)

In France, President Emmanuel Macron’s heavy measures do have a duration of some two months. What has tended to be drowned out is the element of opportunity that has little to do with the virus, the sovereign exploiting the situation to make hay. Being an enemy of the 35-hour workweek and unfair dismissal provisions in the workplace, Macron’s COVID-19 measures give employers full rein to dictate working conditions. As Edward Lee-Six and Véronique Samson put rather tartly in Jacobin, France was witnessing what “seems closer to an opportunistic instrumentalization of the health crisis to intensify police impunity and the deregulation of labour.”

The authors also point out the most bitter of ironies regarding Macron’s measures: the weakening of the underfunded health sector which has left a shortage of qualified staff, beds and medical equipment.

Hungarian strongman, Viktor Orbán, is also aware of the golden chances. Coronavirus has presented him a stunning opportunity to shore up what was already an unassailable position. For years, through the formidable party machinery of Fidesz, the wily politician has been sounding the gong of patriotism and attacking institutions he deems disruptive to the Magyar project. Timothy Garton Ash, that veteran student of central European affairs, has gone so far as to label Orbán the foremost iconoclast of European liberal democracy, having spent a decade or so demolishing it. The independence of the judiciary has been compromised; electoral laws have been amended to keep Fidesz cosily in power; activists have been harassed.

For Orbán, the problem is less the virus itself than other familiar bugbears. “The government wants a strong Europe,” he said during a radio interview on Friday, “but the EU has its weaknesses.” Having failed to arrive at a unified plan to cope with the economic and financial impact of COVID-19, the Hungarian PM seemed filled with that I-told-you-so confidence. “In terms of coronavirus aid, for example, Hungary has received support from China and the Turkish Council.”

The “protecting against the coronavirus” law promises to give the prime minister near dictatorial standing. It vests the executive with unaccountable decree powers, which include extending the state of emergency declared on March 11 indefinitely. The bill enables the executive to overrule lawmakers. It suspends elections and keeps information on government actions in short supply, to be delivered via the speaker of the parliament and party leaders. Journalists face hefty prison terms for reporting on information that might disturb the populace.

The Council of Europe, another one of those bodies Orbán tends to rile, has acknowledged that “drastic measure to protect public health” were warranted in responding to COVID-19. The letter by Secretary General Marija Pejčinović Burić addressed to the Hungarian leader is filled with legal reminders, though the field of states observing them is diminishing. Anti-pandemic measures still had to comply with “national constitutions and international standards”. Democratic principles had to be observed. “An indefinite and uncontrolled state of emergency cannot guarantee that the basic principles of democracy will be observed and that the emergency measures restricting fundamental human rights are strictly proportionate to the threat which they are supposed to counter.” Orbán’s snooty response was dismissive, urging the Council to “read the exact text of the law”.

The law in question also goes to show that the authoritarian can, when needed, adjust his position. Pro-government media outlets had, for instance, insisted earlier this month that the coronavirus pandemic was only deemed such by journalists engaged in “a worldwide experiment” of panic sowing. Whatever his previous views, Orbán is now gratified enough to accept the chances presented by this “invisible enemy” as, for that matter, are many others.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER