Abstract: Even before the full impact of COVID-19 on Health of Indians is clear, the economic impact of the measures to deal with the pandemic are already posing grave concern. The paper highlights the global overview of the pandemic on economic situation. Indian economy was in dire straits even before COVID-19 reached shores. Specifically, the lockdown and other movement restrictions backed by scientific and political consensus on their inevitability, have directly led to dramatic slowdown in economic across the board. Grave danger on Livelihoods of lakhs of Indians posing a wide range of concerns on their income generating and informal activities. Paper analysis the economic impact of already slowing Indian economy in context of livelihood. This conceptual paper also envisages the way forward to deal with livelihood security and economic slowdown in regard to COVID-19 pandemic.

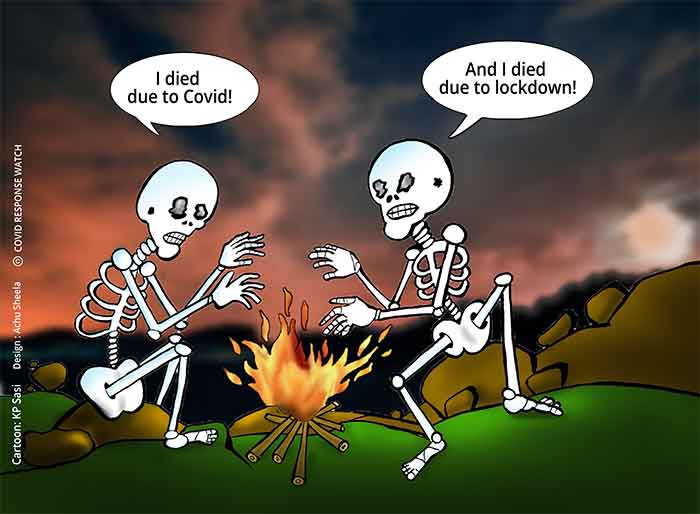

We are now witness to a historical calamity, never seen before. Earlier, either it was an event like say a world war, where lives were stake. Or, it was Great Depression or financial meltdown, that affected livelihoods. But, the present COVID-19 outbreak situation is a dangerous amalgamation of both, threatening life and livelihood alike in virtually every part of the world. To put it in context, it is a potent combination of a World War-3 and Great Depression. The recent report published at King’s college London and Australian National University, warns that between 6% and 8% of the Global population could be forced into poverty. Oxfam has urged richer countries to step up their efforts to help the developing world. Failing to do so, it added could set fight against poverty by a decade and by as much as 30 years in some areas, including Africa and West Asia.

Livelihood and Pandemic: A scenario of Informal Sector:

The “informal” nature of labour work in India means that the lockdown imposed a severe burden on this section of the workforce, which is the prime form of employment in India. According to Prof. K.P. Kannan, who served as a member of the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector, headed by the late Arjun Sengupta, (https://www.epw.in/engage/article/covid-19-lockdown-protecting-poor-means-keeping-indian-economy-afloat), of the 460-470 million workers, about 369 million (more than three-fourths) are engaged in agriculture or work in micro, medium and small enterprises (MSMEs) employing less than 10 workers each. Of the remaining, more than half are temporary or casual workers in the organised sector; the automotive industry is a prime example of organised industry employing workers on contract, apart from the government itself employing an increasingly large fraction of its workforce on contractual terms, often through contractors. Thus, informality is to be seen not just as a monetary relationship but one that is embedded in social relations. The tenuous nature of this relationship could have a significant impact on the nature and extent of the recovery, if and when it happens in the future, to which we will turn to a little later. (Sridhar, 2020).

The lockdown has exposed the existing problem of the devalued labour of 100 million internal migrants workers and an economy that cannot ensure their safety and sustenance. So desperate were these workers to leave the cities and towns where they worked that they left in scores to their villages on foot, braving hunger and thirst, the scorching summer sun, police harassment, forested areas, and the threat of disease and death. For decades, internal migrants toiling in cities have remained uncounted in national statistics, excluded from urban governance facilities and services, and unrecognised either as workers or as citizens by their employers or governments. Before announcing the lockdown, the government had forgotten that its celebrated economic growth model—based on high-growth sectors and world-class infrastructure in large urban agglomerations—is built through the labour of rural-urban migrants. With a large number of intermediaries between employers and migrant workers, they find it hard to identify the employer or even the company that hires them, remaining solely dependent on the petty contractor. Many more migrant workers are labelled as “self-employed” but in reality are piece-rate or home-based workers. They receive work from local agents who pay them a marginal amount based on their output. The lockdown has meant a loss of orders, and these women workers are left with no employer to ask for their wages. When the government announced that employers must pay wages to workers despite the suspension of work, migrant workers were left without standard work contracts or identifiable employers to pay them. (Jayaram & Mehrotra, 2020).

Overall, about 136 million non-agricultural jobs are at immediate risk, estimates based on National Sample Survey (NSS) and Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS) data suggested. These are people who don’t have a written contract and include casual labourers, those who work in non-registered in Nano businesses, registered small companies, and even the self- employed. The coronavirus situation will only exacerbate unemployment. Adecco Group of India, a staffing company estimated that the automobile industry can lose up to a million jobs in the dealer ecosystem, front-line roles, and the semi-skilled. Around 600,000 ground and support roles on contract in the aviation industry are at risk. Santosh Mehrotra, a human development economist and professor at the Centre for Informal Sector and Labour Studies in Jawaharlal Nehru University, pegs India’s labour force at 495 million. In 2017-18, about 30 million were unemployed, which implies that 465 million are currently employed.

Who among the already employed are the most vulnerable? The easy answer is those that don’t have the security of employment; those without any social protection. They are often bracketed as “informal” workers. (Das, 2020)

COVID-19 and Globalisation:

The World Trade Organization has now estimated that in a worstcase scenario, global trade could dip as much as 32% indicating the kind of dislocation they expect in large economies. Already US-China war and Iran Sanctions plus turmoil in West Asia has caused the process of globalisation into hardships last year. The term “slowbalisation” was being used. World trade have never really recovered since the global financial crisis- from 10% growth, it had been hovering around 1% to 2%. Add to that the trade wars and the WTO talks process coming to the halt made the situation worst. Now, with this pandemic there is another recognition of vulnerability that global economic interdependence creates, as lot of supply chains were dependent on China, specifically pharmaceuticals. UNESCAP hs released its annual Economic and Social Survey, it says that the COVID-19 crisis is challenge never seen before and it is going to be a bigger shock for the world Economy than the global financial crisis. It is clear that many economies going to shrink as a result lakhs of people’s livelihood is on stake. (Sachdev, 2020)

Agriculture taking a dual hit of Climate Change and Pandemic COVID-19:

Climate change has been a problem for different sectors and grave challenge for humanity to deal with. It has displaced lakhs of people who lost their livelihood. Indian Agriculture is in grave danger of dual calamities of Climate Change and COVID-19. Excessive rainfall in March 2020 — accompanied by thunder, hail and lightning — severely damaged crops, affecting farmers across the country. The irregular weather patterns come close on the heels of an economic quarantine, itself the fallout of a worldwide pandemic caused by the COVID-19 disease outbreak. The country recorded 77 per cent more rain than normal between March 1 and March 19, 2020, according to India Meteorological Department data. There was large excess rainfall — more than 60 per cent than normal — recorded in 381 districts, 57 per cent of all districts in India. Farmers suffered severe losses from the unseasonal rain and hail, with four lakh hectares of farmland damaged across the country, according to media reports. Around 650,000 farmers in Uttar Pradesh suffered estimated economic losses up to Rs 255 crore, according to Skymet Weather, a private weather forecasting agency based out of Noida. The distribution of rainfall throughout the country was uneven as most of it was concentrated in 13 states and Union territories in the north, central and east central regions. (Sangomla, 2020).

COVID-19 is disrupting some activities in agriculture and supply chains. Preliminary reports show that the non-availability of migrant labor is interrupting some harvesting activities, particularly in northwest India where wheat and pulses are being harvested. There are disruptions in supply chains because of transportation problems and other issues. Prices have declined for wheat, vegetables, and other crops, yet consumers are often paying more. Media reports show that the closure of hotels, restaurants, sweet shops, and tea shops during the lockdown is already depressing milk sales. Meanwhile, poultry farmers have been badly hit due to misinformation, particularly on social media, that chicken are the carriers of COVID-19. (Dev, 2020)

Micro Small and Medium enterprise (MSME) is in Peril:

There were over 6.3 crore MSME in the country, which account for almost half of all exports and the third of the national GDP. They employed 11 crore people, and were struggling to pay wages, given the shutdown of many businesses, the sharp depression in demand and massive cash crunch. The impact on the manufacturing sector will be quite large because people are required to go to their workplaces and that has been curtailed due to the lockdown. The small-scale sector will suffer more than the large-scale sector, as these businesses work with a limited amount of working capital and, as their sales will decline, they will exhaust it. They will retrench workers or if they are self-employed, they will lose work soon and that will reduce demand further. In India, because the small-scale sector is very large, both in number and employment, the impact will be substantial. It is here that the crisis will be the deepest since these workers have the least resilience to face a fall in incomes. This could lead to a societal crisis. (Kumar, 2020)

Analysis and Way Forward:

The Jan Kalyan Yojana: a package of 1.7 Lakhs rupees and unprecedented consistency of a three month- planning and coordination from different stakeholders of government, inclusion of COVID-19 tests under Ayushman Bharat and capping the test price at INR 4500 by private hospitals, and commitment to procure 40,000 ventilators by June 2020 are welcome moves and provide much needed respite. But a detailed strategy for the execution and delivery of services remains veiled. Let us examine the solutions in 5 crucial areas.

Firstly, Food Security: Releasing food is all the more crucial as the emergency cash transfers proposed by the finance minister are likely to have severe limitations. This year, Food Corporation of India, have reached a staggering 77 million tonnes in March, before the rabi harvest, when food stocks typically rise by another 20 million tonnes or so. Public food storage on this scale has never happened in India before. Meanwhile, the shadow of hunger looms large as the lockdown devastates people’s livelihoods. (Dreze, 2020).

Government of India should release this excessive food to marginalized households even without asking for any kind of documents like Ration Card, or Aadhar. Secondly, Solution to Agricultural Activities: It’s a Rabi harvesting season and farmers can’t just sit and wait for his crop to destroy during the lockdown. I think government should come up with some plan to transfer farm produce to local markets. Organisation like NAFED and E- Nam portal must be activated to do marketing for the farm produce. Farmer Producer Organisation can act as a link between markets and Farmers to carry farm activities. Several states have set deadlines to procure farm produces, I think keeping supply chains functioning well is crucial to food security. It should be noted that 2 to 3 million deaths in the Bengal Famine of 1943 were due to food supply disruptions Thirdly, Package for Small plus Medium sized business. As proposed by Jayram Ramesh, congress leader Centre to set up a Rs1 Lakh crores corpus fund as part of a relief package for the sector, tax sops and another measures to ensure liquidity, preventing mass unemployment. Ensure payment to daily wage earners and self- employed workers announced in Jan Kalyan Yojana. Fourthly, Suspend fiscal limits for states and centre for a year. Amend FCRBM act 2003 and come up with such measure where states and centre has not abide to fiscal limits when it comes to saving lives.

Lastly, use of grassroot institutions like Panchayats and Self Help Groups in containing COVID-19 through various measures. When States are fighting to its full potential grassroot institutions can be very crucial as every village is in itself a fortress during these difficult times and every village needs attention with the influx of thousands of migrants labourers into their villages, there is imminent need to isolate them at least 14 days, where panchayats stakeholders can be handy. Same with Self Help Groups, as we have immense demand for food and cooked meal, government can set up community kitchen run by SHGs. The government must Fastrack all these measures to control the situation s I believe it’s a fight where community participation is very crucial.

Bibliography

Sachdev, M. (2020, April Friday). A double Whammy for India- Gulf Economic ties. The Hindu, p. 6.

Sridhar, V. (2020, April Friday). Economy in Deep Freeze. Frontline.

Jayaram, N., & Mehrotra, R. (2020, April Saturday). Frontline. Marooned in the City.

Das, G. (2020, March 31st ). 136 million jobs at risk in post corona India. livemint .

Sangomla, A. (2020). Excess March rainfall: What it means for COVID-19 outbreak. . Down To Earth , 1-5.

Kumar, A. (2020, April 14). Impact of Covid-19 and what Needs to be Done . Economic and Political Weekly.

Dreze, J. (2020, April 9). Excess stocks of the Food Corporation of India must be released to the poor. . The Indian Express, pp. 1-4.

Dev, S. M. (2020). Addressing COVID-19 impacts on Agriculture, food security, and livelihood in India. Washington DC: International Food Policy and Research Institute.

My name is Lavrez Chaudhary, I have completed my Masters in Social Work from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. After completion my masters, I have worked with Rajasthan Government at Rajasthan Gramin Ajeevika vikas Parishad, Ministry of Rural Development and Panchayat Raj as Young Professional for more than two years.

Email Address: [email protected]

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER