Being in the extreme Northeast of India, this region of seven States and more than 45 million people has always found itself at a disadvantage because of poor communication with the centres of power. Moreover, the whole region with only 22 members of Parliament has very little power of advocacy. But in the initial stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic its relative isolation turned out to be a blessing in disguise because the virus took a long time to reach the region. Nearly a week into the national lockdown the Northeast has only two confirmed positive cases – a 23-year old woman who returned to Manipur from UK on 21st March after completing her doctoral studies and a Baptist pastor who returned to Mizoram from the Netherlands two days later. The real number may be higher than this because testing is low in India. But in the Northeast it is bound to be much lower than in the rest of India.

That advantage can disappear in the next few days. Because of high unemployment in the Northeast a large number of its youth migrate to cities in peninsular India (known in the region as Mainland) in search of unskilled or semi-skilled work in the hospitality industry, as security guards and other low-paid jobs. Around 100,000 of them have come back from cities where the pandemic has spread since the enterprises where they work have closed down or have suspended operations because of it. One will know during the next few days whether they have carried COVID-19 with them. Testing which is low in India is to a great extent limited to air travel, especially to foreign travellers entering India. According to a news item (Times of India e-paper, 29th March 29, 2020) India tests only 19 persons per million, the lowest in the world, the next lowest being Japan with 319. Testing is slowly being extended to train travel. But the migrants of the Northeast have reached their villages already without being tested. As a result, one may not know the extent of the spread of COVID-19 immediately. Testing is non-existent and health services are poor in their villages. The lockdown can prevent the spread of the disease where social distance works. Most returnee migrants live in small houses in which it is not easy to enforce social distance. So if they are infected already they may spread it to others. One will know it in the next few weeks.

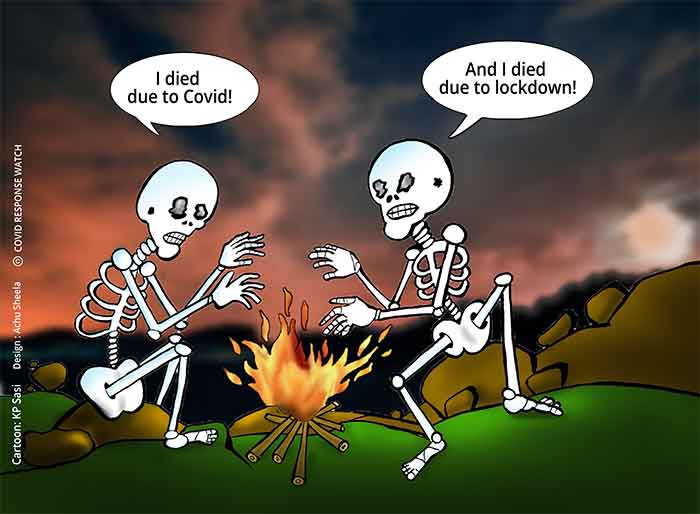

The danger of the virus spreading is only one aspect of the pandemic. Of equal importance is the economic pandemic. Even if the disease does not reach the region through the migrant workers, the returnee migrants and their families face an economic disaster. Like migrants in the rest of India they too were holding low paid jobs and do not have savings to tide over a crisis of this magnitude. At present they are without work, without social and financial security so they and their families may face even starvation. The economic pandemic is not limited to the 100,000 returnee migrants. The region also has lakhs of migrants from other states like Bihar and from Bangladesh. They sustain themselves through daily wage unskilled work. With the lockdown they are deprived of such work with no alternative and they too face starvation.

To this danger has to be added racism linked to the virus. With Mr Donald Trump many people in Mainland India call COVID-19 the Chinese virus. A relatively large number of migrants from the Northeast have Mongoloid features. Because of it in the cities to which they migrate, they are taunted as Chinese or Chinkis and as carriers of the disease. For example according to a news item three students from Nagaland were denied entry to a mall in Mysuru because of their ‘Chinese’ features. Others from the region have complained of some locals taunting them as Corona. For example in her blog Dr Alana Golmei from Manipur who now resides in Delhi and is General Secretary of the Northeast Support Group recounts how on three different occasions the staff of NCERT taunted her and her companion from Meghalaya taunted them as “corona virus” when then entered the NCERT campus. They apologised when confronted by Golmei. A nurse from the Northeast working in Bengaluru recounts how a small child pointed to her, shouted ‘corona virus’ and ran away out of fear. She asks whether children are born racist or are made so by their parents. Many landlords have asked the North Easterners to vacate their premises though they do not want to return to the Northeast. Thus they are subjected to a racist pandemic. One has also to be on the lookout to see whether the villages to which they come back discriminate against the returnee migrants as possible carriers of the virus.

The civil society (CSO) in the Northeast has to face this challenge. Many civil and church representatives led by the Inter-Agency Group (IAG) met on 27th March in Guwahati to look at the possibilities of coming together to prepare food packets for the migrant and other workers who face starvation. They have worked out a plan and have asked for permission from the district authorities. This permission is still in the pipeline at the time of writing. They want to go beyond relief to ensure that the Central and State government packages for the poor reach the needy.

This is a major challenge that the CSO and church groups should face and on which they should work together. They should also realise that this is only the first step and they should go far beyond it once the lockdown is lifted. The health infrastructure is extremely poor in the region. Government health services exist only on paper. The pandemic can spread if a proper infrastructure is not built within the next few weeks. The CSO-Church combine can do it. Unlike in the South where by and large these bodies run hospitals on a commercial basis, in the Northeast their infrastructure consists mainly of rural dispensaries. In the seven states together they have only four hospitals, all of them run on a charitable basis. But their dispensaries render yeoman service without getting any funds from the state. This rural infrastructure needs to be activated on a permanent basis. On one side, the CSO and church groups can put pressure on the state-run health services to function properly. On the other, together they can demand that the state fund their dispensaries in order to ensure that a good public health infrastructure is created. They cannot run away from this challenge of building a permanent effective health infrastructure in order to prevent future pandemics. They have to accept this challenge as intrinsic to their mission.

The writer is Director of North Eastern Social Research Centre, Guwahati. [email protected]

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER