Sadgati (1981) marked a watershed in Satyajit Ray’s career. He suffered a massive heart attack soon after Sadgati was in the can, and never recovered fully from the blow. And he was not quite the same artist ever again. You realise this as you watch Sadgati after several years, as I happened to do recently, and look back to Shakha Prasakha, or any of three other features (Ghare Baire, Ganashotru and Agantuk) Ray made between 1984 and 1992, when he died. Sadgati was the last great film to have come out of the Satyajit Ray stable.

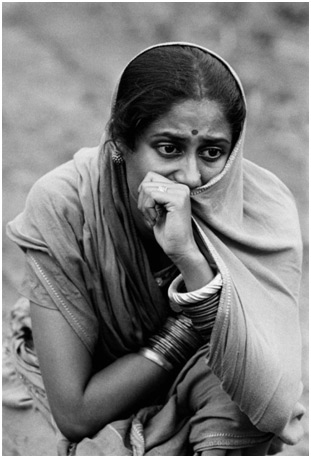

And since it was made for television, it is special even in such a distinguished oeuvre as Ray’s. For one, it is short, running to just about fifty minutes. A simple, unilinear story and sparseness of both dialogue and background music are its other distinctive features. Indeed, the impression you take away from the film is of an extraordinary economy of expression. And of great intensity. Such great intensity that, at times, you catch yourself looking involuntarily away from the screen. For example, when Dukhi (Om Puri) hacks away apoplectically at the monstrous block of wood without making the slightest difference to its hulk, his face contorted in anger and desperation. Or when a devastated Jhuria (Smita Patil) cries inconsolably, as she hears Dukhi is dead, her sobs rising steeply above the surrounding sounds of a perfectly ordinary village evening.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rRpaPV3QayY

Like all great Ray movies, Sadgati peoples its plot with fully believable human beings, not stereotypes, even less with caricatures. As utterly sanctimonious and self-aggrandising as he is, the Brahmin (Mohan Agashe) is nevertheless an authentic figure in his own right, as is his petulant and unfeeling wife who thinks nothing of throwing a smouldering piece of firewood at the lowly Dukhi (a chamar, or professional tanner, an ‘untouchable’) when he makes bold to ask for a fire to light his clay briar with. Or of telling her husband that the chamar has no business expecting to be fed by them, no matter that he has been slaving away over that incredible hulk of wood at the Brahmin’s insistence. The frothy moralistic flummery to which the Brahmin treats his two devout visitors – when he goes on about life being but tattered clothes to be flung away for the divine to manifest itself – is pure nonsense, of course, but he pulls it off with elan, without allowing it to look, or sound, one bit like a parody. As the Brahmin mouths that eloquent homily about death and after-life, Dukhi enters the frame of the shot, hesitant and apologetic, foreshadowing his own death which will come in a little while from then.

Sadgati tells a grim story, the grimmest perhaps of all Ray movies, but that does not stop Ray from leavening it with gentle humour – the kind of refreshing, unselfconscious humour that you come across in nearly every great Ray film. (An element entirely missing from his last few movies, though, and this is another feature which sets his best work apart from his second-best.) Dukhi asks Jhuria to ‘recite’ the grocery shopping list that he has just asked her to memorise – and she fumbles, to Dukhi’s exasperation. Sometime later, Jhuria unloads that list on the village grocer – and, in trying to remember the items, he fumbles exactly as Jhuria had done in the first place. The irony is not lost on the artless Jhuria, who breaks out into a ringing laugh. The sprightly little girl — Dhania — whose intended marriage is what launches the story, animates the plot like a whiff of fresh air even as she capers and skips about their hut or plays at her own solo games in the courtyard. In another deft touch, Ray has the same herd of cattle that overran Dukhi in the morning, as he left home never to return, overrun Jhuria in the evening as she, distraught on learning about Dukhi’s death, collapses in a heap on the slushy village road. The herd that left home in the morning returns in the evening, but not Dukhi.

Sadgati – meaning deliverance –is pivoted on an indictment of untouchability and of the caste system in general. It is a savage indictment, pressing its charges with relentless intensity, but doing so through purely visual statements. The Brahmin must dispose of the chamar‘s corpse quietly. He proceeds to deliver Dukhi’s body to where animal carcasses are landfilled. He has no one to turn to for help, and thinks up an ingenious method of doing his job while preserving his caste sensitivities intact. As he hauls Dukhi’s body over a rugged terrain, he pants and huffs from its heavy weight. He is mortified that he is reduced to doing this, but believes he has stayed ‘clean’ throughout his ordeal. As he nears his destination, we are not sure if it is dusk or dawn. A curious half-light etches his lumbering frame against the horizon, the half-light of that limbo between life and death, hope and despair which holds the viewer in thrall. It is one of the high points of Indian cinema, a summit Ray himself touched only rarely. Sadgati is an angry, angry film, but its anger is not the kind that sets off a bomb with a huge racket; it is anger that pulsates like a fully stretched bow-string, taut and quivering, as Ray himself said once. And Om Puri and Smita Patil once again showed us why they are considered two of our finest dramatic actors across all languages.

Anjan Basu freelances as a cultural commentator. He can be reached at [email protected].

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER