The word “prophet” is rooted in the Greek word prophetes, a word that breaks down etymologically into “to speak before or foretell”. A soothsayer is considered a prophet in the sense that he foretells events. Such is the soothsayer in Julius Caesar who tells Caesar to “beware of the ides of March” when he was doomed to assassination. The Prophetic books of the Old Testament inform the people of Israel what God desires of them and what will happen if they disobey His commands. In Amos 3:7, it is written: “Surely the Lord GOD will do nothing, but he revealeth his secret unto his servants the prophets.” This designates the place of the prophet as one who knows God’s secrets. Amos reveals that the prophets had been instructed to remain silent until the burden became too great. Throughout Scripture, there is a love for justice which maintains the distinct definition of sympathy for the disadvantaged, and upholding God’s Word. A prophet is thus one who speaks on behalf of God Himself. The prophet Amos indicates throughout that the Lord will speak when He is out of patience. God is a God of all nations and will not tolerate disobedience even from Israel.

The Arab poet, Adonis, said, “It is an awful idea that after this one prophet, after this one book, everything would be said and written, isn’t it? If Mohammed would really be the last of the prophets, then no human word can be uttered anymore, and even much more frightening, no divine word either. The holy book is a trap closing in on us. Every monotheistic religion has the same problem. Christianity had the chance to avoid the trap but it didn’t. It identified itself with power and it embraced dogmatics.” Here we have a radical view that prophecy continues in the modern world. Richard Wilbur in “Advice to a Prophet” writes:

“Nor shall you scare us with talk of the death of the race.

How should we dream of this place without us?—

The sun mere fire, the leaves untroubled about us,

A stone look on the stone’s face?”

Here the poet is a prophet of a particular kind. Bringing God’s message to the people becomes something peculiar— in this, the prophet defines the meaning of humanity. The role of prophet in Wilbur’s poem is one who does not warn of the imminent threats to human life, but rather defines the human role within Nature and Being itself. The modern reflection of God is much more personal and forgiving. As stated by Adonis, Christianity could have unleashed the powers of human language but, instead, gave way to power structures. Language carries the unique gift of uniting disparate things. The power of analogy is that of reconciliation. The poet, with his or her unique gift, invites comparisons between things that have little in common as if to agree with Heraclitus who wrote, “All things contain their opposites.” Perhaps not their opposites, but definitely things of dissimilar nature. The dark contains the light, and the light is contained by the dark. One interiorises the other. This strange capacity of language to reveal what is concealed in the dark is a magic of its own. A word is a form of conjuration, something brought into being by shining a light on it. That light itself is the poem—a unified body of language that conditions the reader to a certain subjectivity, thus causing the reader to recognise some hidden aspect of him or herself.

What is this thing of revelation? “Apocalypse” is from the Greek apokalupsis which means to unveil, uncover. The nightmarish visions portrayed in Revelations are considered to be end of the world prophecies. The opening of the scrolls, the rivers of blood, the hellfire and dragon tossed into the pit: these things are seen as happening at the endtimes. This branch of Biblical study is called eschatology. What is it that eschatology uncovers? What is God unveiling to us in His prophetic writings?

Is it that true theology, the branch of learning concerned with the study of God, includes a side of God we are less acquainted to receive and understand? In Answer to Job, Carl Jung proposes what he called the Quaternity. According to Frith Luton, “The quaternity is one of the most widespread archetypes and has also proved to be one of the most useful schemata for representing the arrangement of the functions by which the conscious mind takes its bearings.” In Answer to Job, Jung writes of Job himself, “Because of his littleness, puniness, and defencelessness against the Almighty, he possesses, as we have already suggested, a somewhat keener consciousness based on self-reflection: he must, in order to survive, always be mindful of his impotence. God has no need of this circumspection, for nowhere does he come up against an insuperable obstacle that would force him to hesitate and hence make him reflect on himself.” The Quarternity is an extension of the Trinity. Jung believed the traditional conception of God was lacking. He invented the Quarternity to define the evil face of God. Thus, God becomes a holistic vision of the cosmos.

In Answer to Job, Jung portrays a human god who is capable of feeling guilty. In the end, Jesus is sacrificed not to cleanse humankind of sin but to rid God himself of guilt. Why wouldn’t God share the being of that created in His image? However, traditional theology includes a study of theodicy or reconciling divine goodness with the existence of evil. The ultimate question is why God might permit evil. We might even ask what constitutes a definition of evil. C. S. Lewis writes in Defense of Christianity, “God created things which had free will. That means creatures which can go wrong or right. Some people think they can imagine a creature which was free but had no possibility of going wrong, but I can’t. If a thing is free to be good it’s also free to be bad. And free will is what has made evil possible.” However, the definition here has an inevitable fallacy. In using free will to excuse God of wrongdoing, Lewis tells us he cannot imagine a free creature that has no capacity to do wrong. In applying this logic to God Himself, we are left with two possibilities. Either God isn’t a free creature, or God is also capable of wrong. In what capacity could God not be free? God is seen as “omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent.” He is defined as sui generis, a being that causes itself. How could a self-caused being not maintain perfect autonomy? If God has will, He must have the ability to err if we take Lewis’s definition at face value.

Continuing along my original line of inquiry concerning the Apocalypse. What does it say about God’s nature? One, it demonstrates that we as fallible creatures are capable of causing great destruction. Why is that quality inherent in us? The Apocalypse, or “unveiling”, is shown to be final — creation is revealed for its full promise. The conclusion of time is the extinction of choice — it is ultimate revelation of true being. All secrets come undone. The lid to Pandora’s box is unclasped and all evil is unleashed. This tells us that something is hidden within Creation itself. Our awareness is incomplete. The Apocalypse completes that awareness and shows us the purpose we missed—complete annihilation. Why should God desire the annihilation of His creation? Why did He command the death of His Son as a sacrifice to the world?

Humankind is bent on forging a utopia, a paradise that lasts eternally. Behaviorist B. F. Skinner invented a utopia based on his model of psychological conditioning where people are entirely robbed of choice. Instead they are conditioned by authorities to fit their chosen roles. This theory is presented in Walden Two. In this novel, Skinner applies his understanding of behaviorist psychology to the creation of a perfect society. Children are conditioned to perform certain roles from the onset. Each person has a role chosen for them. What we don’t consider is who is making the decisions for the roles given to each person. By nature, this model eliminates choice by individuals—yet how is there any order without choice? The authorities are making the ultimate decisions but who chooses that role for them? In this utopian vision, we see a flaw inherent in the system itself. Humankind is robbed of “freedom and dignity” for the sake of a perfect community conditioned to serve the aims of the community as a whole. Yet what criteria is used to sponsor this concept of communal well-being? Again, who decides?

Aldous Huxley presents us with a similar enigma in Brave New World. This is a utopia that is so oblivious to its flaws that it is dystopian to the onlooker. People are robbed of dignity again, but in the process, they become childlike in their understanding. Human misery is alien to them because they take measures to eliminate it and inoculate themselves from it. The results are the same. We are left with a set of social engineers who demonstrate scientific objectivity in their observations. They comment on the community, applying their superior awareness of things. Knowledge is too specialised in such a community. It becomes the risk of those designated to “know” rather than the shared offerings of the community. So much for community.

Lois Lowry’s The Giver is another dystopian vision where knowledge becomes specialized for a few. The Giver is a person who is entrusted with the collective history of humankind, and this person imparts it to another person as the role is relinquished. This arrangement resembles the pagan priesthoods where the Eleusinian mysteries were kept secret exempting those initiated into the sacred cult. What did these secret rites entail? No one knows because they are extinct. However, the parables of Jesus Christ contain a certain mystery to them. They are the prophecy of God in themselves. Jesus was known for his unique gifts of teaching and language. The ancient prophecies concerning him told us that he would not be physically attractive so that his message would be the accent of his coming to the earth. In Matthew 13:11, Jesus answers his disciples who ask why he taught in parables. “He answered and said unto them, Because it is given unto you to know the mysteries of the kingdom of heaven, but to them it is not given.” So, what are the rites of the initiated?

Paul the Apostle writes in 2 Corinthians 4:4, “In their case the god of this world has blinded the minds of the unbelievers, to keep them from seeing the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God.” Jesus is also described as the unveiling in various verses—thus the Apocalypse is understood as the wedding of the Paschal Lamb. In Exodus 12, the Paschal Lamb is the sacrifice whose blood is put on the doors of the firstborn of Israel so the avenging angel would spare them. Jesus Christ is seen as the Paschal Lamb in the New Testament whose blood protects believers from the avenging angel, or Satan. In Revelations 19:7 it is written, “Let us be glad and rejoice, and give honour to him: for the marriage of the Lamb is come, and his wife hath made herself ready.”

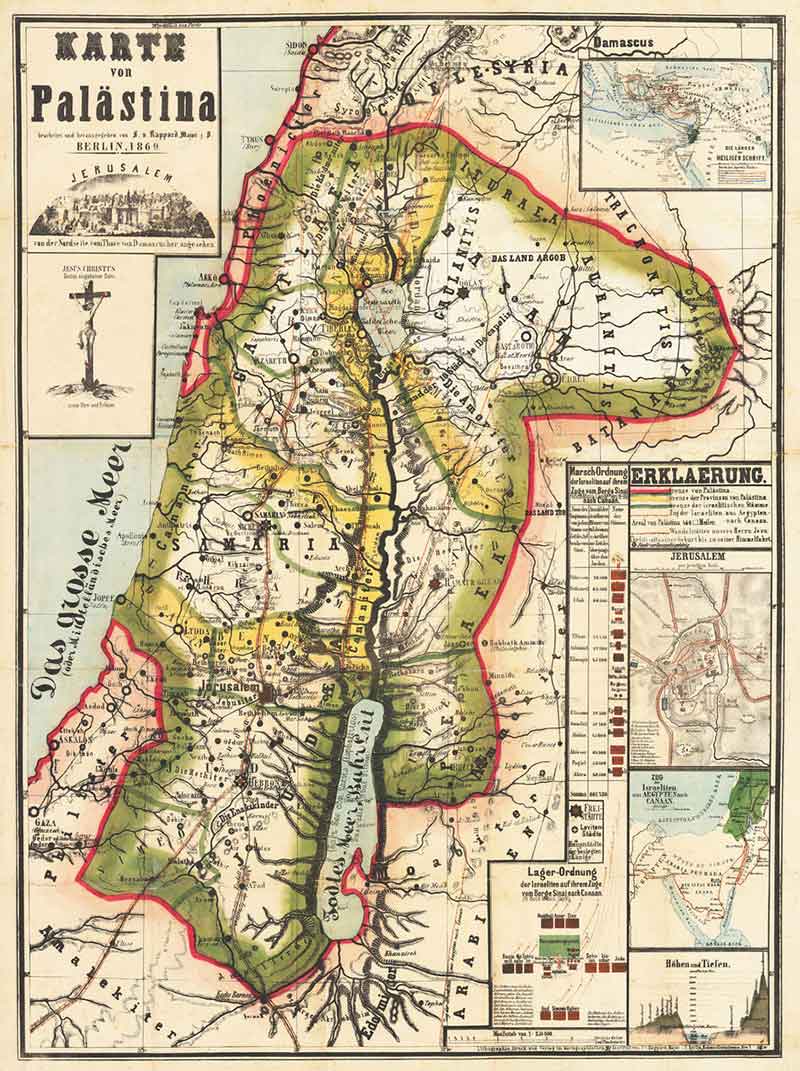

It seems God spares those He decides to spare. The firstborn of Israel were spared by Moses’ prayer and desire for their freedom from Egypt. One man’s strong desire for the justice of his people pleases God. As we know, Israel would later also sin and be condemned. However, the revelations of Israel became the truth of all of the nations and God’s people span the entire world.

The relationship of utopia and apocalypse is nowhere more apparent than in the Holy Bible. God defines Israel’s purpose. History shows they failed in acknowledging God after His power rescued them from Pharaoh. Even Moses came up short of God’s will and was not permitted to see the Kingdom of God. One universal truth of Scripture is that all of us, no matter how holy or chosen, fall short of God’s grace. It is thus we see the emergence of Original Sin. Original Sin is itself a revelation of St. Augustine, early Church father and Christian apologist. He began his journey in truth as a Manichean. In Confessions, he tells us that God showed him the error of his ways. It was then he discovered the power of Original Sin—that darkness cast on the world by Adam’s first disobedience. We are created in God’s image but are not God Himself; Jesus Christ alone is seen as the true image and equal of God in his Passion and innocence.

In short, utopia is the promise we can redeem ourselves with radical changes to our world or relations. Utopians tell us that their vision is superior and if we conform to it, we will all be better off. Politicians are often utopians with realist proclamations. They desire to shape the world in their own image, as God did with us, and grant us our salvation. The poets use utopia as a vision—it becomes a kind of mnemonic device in understanding the nature of the world. Prophecy is a revelation of utopia—which is modeled after God’s being. Our concepts of goodness are even deficient, but we all desire to live in a world of productivity and happiness for all. A poet casts his or her eyes forward to a world known in the imagination. Such visions shape the world as ideas and influence our thinking. The Romantics, for instance, were conservative republicans. They desired freedom from authoritarian righteousness—both political and religious autonomy. William Blake, an Anabaptist, voiced these visions the best in All Religions Are One. He writes, “That the Poetic Genius is the true Man, and that the body or outward form of Man is derived from the Poetic Genius.” He further explains that all nations experience this poetic genius differently. He defines this capacity as prophecy. Our true state of Being is poetic. Our form is a distinct relationship to that poetic being. Poetry, then, is being itself expressed in variety.

I remind the reader again of Heraclitus: “All things contain their opposites.” Therefore, what we see conceals a deeper mystery and faith. Even consciousness withholds certain fundamental values and truths from us. The unveiling of those values and truths has great destructive and restorative power. The Apocalypse is a lifting of the veil of consciousness to bring the powers of wholeness to Being. It is ultimate light and extinction—and therefore it is a vital annihilation. The power of chaos is spoken of in Genesis where we see God wrestling with the deep to create a new world. The creation of a new world from rough matter is the very act from the spirit of utopia. Utopians desire to restructure existence to perfect it. God summons His powers of light to unveil the cloud of unknowing.

Poetry as Being and Knowledge is the truth of God. It declares itself to the world and seeks to order it and restore its original purpose. However, the poet is largely unconscious of this power when he or she writes. Language is the poet’s tool. The poet casts language like a net to gather truth and display it to the world. The poet is a maker, a prophet, a seer, a utopian radical.

The Poet is the sheer image of God and the shadow of Christ’s spirit.

Dustin Pickering is the founder of Transcendent Zero Press and editor-in-chief of Harbinger Asylum. He has authored several poetry collections, a short story collection, and a novella. He is a Pushcart nominee and was a finalist in Adelaide Literary Journal’s short story contest in 2018. He is a former contributor to Huffington Post.

Originally published by Borderless Journal

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER