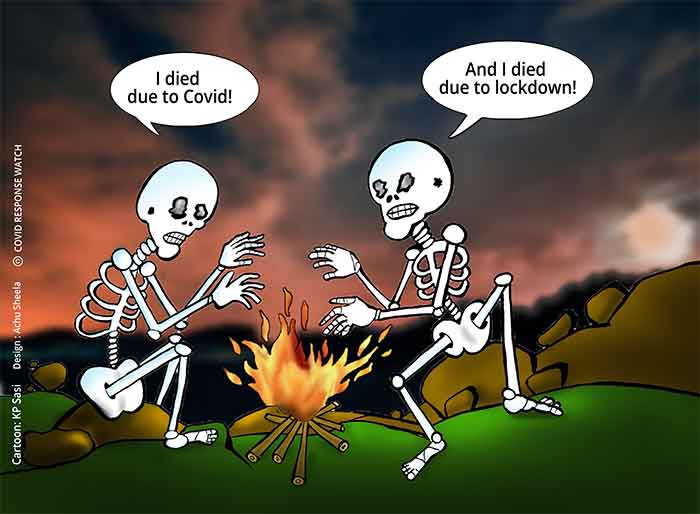

The social implications of the corona pandemic in India are proving to be as grave as its pathological ones. The country’s resolve to fight corona- by no means insignificant- has, however, led to certain outcomes that have caused reprehensible damage to the social and moral constitution. The reported twenty-two people dying on the roads- trying to reach a ‘safer’ place from where, their ‘responsible’ fight against the virus would have begun- is no mean number. The forced flight of tens and thousands of people, along with their families- the infants, the elderly, the ailing- from the cities to their native places, are stories depicting hopelessness and despair in the face of impending crisis. It is hard to miss the chaotic images as they crowd our television sets, of migrant workers in the megacities, battling at railway stations and bus stops for a ride home. The horrific stories of the labouring poor as they throng the roads to walk all the way to their native places, sometimes more than a thousand kilometres, is surely baffling. It is sadly believable when a sympathetic news reporter informs us of what the ‘fleeing’ people fear the most: not the deadly virus, but having to cover miles with no surety of either food, or water or shelter.

It is in times such as these that the deepest of the fissures that underpins our society comes to the fore in all its nakedness. After all, the strange, yet understandable phenomenon of people- with a conspicuous class identity- compelled to leave behind their jobs and workplaces in times of distress such as these, is a peculiar feature of a country like ours. The underclasses of the megacities- the labouring poor, the slum-dwellers, the migrant laborers, the construction workers- scrambling to keep their jobs or for daily necessities in the lockdown period is indicative of how social and economic inequalities that are deep-seated in the structure of society, acquire new and vulgar proportions in the face of corona crisis. That the present crisis has posed insurmountable problems for a certain class of the already marginalised communities- the urban poor- is out there for everyone to comprehend. It appears as more problematic that the ever-deteriorating condition of the labouring poor in the cities has escaped the notice or concern of the authorities, proved by the fact that these very conditions conjure up only a fleeting mention in the ‘public’ addresses of the prime minister.

Several conjectures enter the psyche of the privileged as they try to make sense of the whole situation from the safety of their drawing rooms. For the privileged classes who can afford to keep themselves safe by staying indoors, it looks as if the poor, without masks or sanitizers or the required social distancing, deliberately seek to ridicule the crisis looming large over the country that is on the verge of entering the stage three of corona spread. And, as the privileged sections physically distance themselves from the deadly virus behind the safety of the closed doors, they also externalize the people and the communities which are very evidently the worst-hit from the corona crisis. Casting their disappointment and anxieties over those less fortunate, the privileged sections refuse to understand why ‘they cannot stay wherever they are’.

The world of the ‘rational’ citizen

In the eyes of the state, it is the privileged sections which constitute the ideal crusaders against the fatal disease. The middle and the upper classes, very dutifully, bought the masks, the sanitizers and the disinfectants. They stockpiled the groceries, and even signed up for the online doorstep delivery portals. They dutifully locked themselves in, resolving to contribute to the country’s fight against the deadly virus. And, as the country slowly inches towards the end of the lockdown, and wish for all of this to get over, they plan out their time that is suddenly freed from the exigencies of routinized life and work. Besides the work-from-home hours, they have plenty to look forward to: taking care of self and the family, catching up on their hobbies, a movie here and a book there. Enchanted they watch extraordinary lives turn ordinary; a glamourous actress playing housewife, a heartthrob getting a hair massage from his mom, a cricketer singing out from his balcony. With sheer romance in the eyes, they gaze upon a star couple working out together at their home gym, they get a sneak-peak into the libraries of big personalities, read about the breeziest of outfits actresses spend their lockdown time in, they feel cheered up as our trusted news anchors engage in a round of on-air antakshari and what not. As the privileged sections settle into the microcosm of their private lives, they familiarize themselves with what the ‘rest’ of the world is doing to fight the crisis. All of this generates a feel-good factor, but more so, it makes them feel part of one community, living and fighting the fateful disease as it awaits them outside their doors. The resolve to defeat the virus also includes fulfilling the ‘civic’ duties on the call of the prime minister, as was recently witnessed in ‘thali-tali bajao’, and ‘lighting candles’ which the public complied with, with rather much jubilation and euphoria, almost bordering on a celebration, aptly reported as ‘corona ke khilaf, bharat ki diwali’ by some news channels. While the rest of the world struggles to pace up the efforts to produce as many masks, ventilators, personal protection gears for the doctors and nurses, we show our ‘tenacity’ to fight the virus from our windows and balconies by lighting candles and beating utensils.

What is more disappointing is that this is all that the government wants from us. The privileged sections very neatly fit the bill of an ‘active’ citizenry. We know how to take care of ourselves and our families when asked to do so. We are not perplexed by the fact that in a democracy, the legitimacy of the state rests on how well it is able to fulfil its responsibility to take care of its citizens. In the current scenario, as the state fails miserably to provide even the basic needs, let alone masks and sanitizers, for as close as millions of citizens in our country, we choose to look in the other direction, which in turn, contributes to normalizing a particular form of rationality: a rationality that rests on the notion of self-care, which also, incidentally, becomes a criterion of citizenship. A rational citizen understands the need of the times, the need to take care of self, and by taking care of self can one also contribute to nation’s struggle against the virus. Those who are bereft of this rationality- like the hordes of people on a ‘run’ in time of crisis- do not qualify as citizens or for any of the entitlement it accrues. It almost seems to justify the treatment they receive on their way: brutal police beating, forceful detention, ‘chemical’ spraying, lack of any institutional help in terms of food, drinking water or medical care. All seems legitimate in the name of containing the deadly disease, and reigning in the blatant ignorance and recklessness reflected in the actions of certain communities, that are assumed to be responsible for the disease’s faster spread.

The rationality of self-care underlying the definition of a ‘responsible’ citizen is distinguishable by its closeness to or dependence upon the market or privatized resources. The market is there to assist in the face of a host of challenges thrown up by the current crisis situation: we can buy the required masks, order sanitizers online and get home essentials delivered at our homes. Recourse to private health care, that provides for the expensive corona test is available to the lot of us who can afford. Thus, what is also enabled is the idea of a very individual, personal battle against the virus. In their personal spaces defined by ‘exclusive’ safety and privacy, the privileged sections fight an individuated battle against the spreading disease with a range of market solutions. While all of it sounds fair, considering we all are rational economic agents in the age of the market, who look to optimize every situation in life, it does contribute to the ‘otherization’ of those who are on the wrong side of the world of marketized and privatized services and solutions. These million ‘others’ do not partake in the enthusiasm of the market because they cannot afford its ‘inclusivity’. Their best bet is public utilities, like public health care, ration and public transport, and when the public infrastructure- as it is, on very shaky grounds- dismantles completely, the people dependent on it are thrown on the roads at the expense of their lives.

The imminent social crisis

We must realize that the current crisis represents a social problem, the struggle against which cannot be limited to individual responses by the ‘responsibalized’ citizenry. Neither is the resultant institutional and infrastructural break-down limited to being a feature of the present-day crisis only. We must understand its age-old and deep-rooted origin to see how a health-crisis like corona is allowed to render millions of people job-less and home-less. The almost criminal negligence on the part of the state to come up with a viable plan for the teeming millions who have been left to fend for themselves in times such as these, must be questioned. It must be asked as to why in such troubling times, the government is not ready to spend more than a meagre 0.5 per cent of its GDP on health infrastructure. Rather than feeling elated at a false sense of appreciation that we are ‘doing our bit’ in the service of the nation, we must problematize the current scenario when the government pleads the citizens to take care of themselves. Those worn out by the biting economic inequalities of the times cannot be reduced to being a collateral in our fight against the corona- we must ask why the government is treating them so. The recent incident of hundreds of migrant workers, reportedly ‘rioting’ on the streets of Surat do not represent deviation, rather they hint at the real, human cost of the financial crisis that stares in our face. All they ask of the government is to either reopen their factories for work, or allow them to go to their native places. As a collective, we must acknowledge that their rights are as important for a system of inclusive democracy to develop. In her critique of neoliberalism, Wendy Brown (2007) tells us how privatization becomes a value and practice entering deep into the lives of the citizen-subjects. However, the normalization of a rationality that treats freedom as a private commodity to be enjoyed by those who can afford it, must be fiercely resisted. The true test of the time calls for extending the same freedoms to those who do not form part of our immediate personal lives. The gross indifference and unaccountability reflected on the part of the state and society towards rising inequalities and systemic deprivation must be challenged. which has made corona a bigger social, economic and political crisis than what it already is.

Therefore, while the ‘I-am-saving-lives-by-staying at home’ motto makes sense because it seeks to fulfil the basic requisite of social distancing in the fight against the contagious virus, we must think- and think hard- of our responses as a community to many social and economic fault-lines, made prominent by the recent crisis. Couple of days ago, several Muslim gujjar families, including women and children, were thrown out from the Hindu-dominated villages of Hoshiarpur in Punjab on the charges of spreading the virus, in the wake of the Markaz debacle in Delhi. In Gumla region of Jharkhand, a youth was killed in the course of altercation between the two communities, arising out of a rumour that the Muslims were deliberately spreading the virus by spitting around. According to a data by the National Commission of Women, there has been a twofold increase in domestic violence cases across the country in the lockdown period. The lockdown has made women more susceptible to domestic abuse, and no recourse to report their abuse outside their homes. Similarly, the number of cases of abuse and violence against children inside the homes by family members and caretakers has seen a sharp increase. There have been cases of dalit and Muslim victims of COVID-19, being denied medical care, and even burial grounds in cases of deaths. All of these, among others, constitute the ‘unintended’ consequences of a health crisis, how the social and moral fabric of a society comes completely undone under its pressure. Does our nation-wide struggle against the virus even begin to address these tragic issues reflecting grave human injustices?

The final task of showcasing genuine responsibility would be to pause for a moment to think about the lot of our fellow citizens who are running not so much from corona, but from their economic circumstances. We must understand that to ‘quarantine’ the labouring poor from their work and minimum wage, is not a temporary measure in face of a crisis. Rather, it is similar to uprooting them from the material conditions of life, not to mention, the indignity which is inflicted on them by shutting doors in their faces. It may appear that the ‘civilized’ existence of the privileged is in no way related to the world of the poor and the marginalized. However, these very people form the crucial yet ‘invisibalized’ labour that constitute the backbone of urban economies. They are our construction workers, security guards, rickshaw-pullers, vegetable vendors, maids and gardeners, mall employees, grocery shop workers, delivery boys and the like who work in the service of the privileged. These are the people who have been the most expendable ones, as we oust them from their life conditions in the name of lockdown, and who do not figure as a major concern in the policy responses of the state and the administration. Is it too much to say that as a society, we have failed them?

Shashwati is Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science at Mata Sundri College for Women, University of Delhi. She has completed her Ph.D from Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Email: [email protected]

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER