Co-Written by Sanghmitra S Acharya, Sunita Reddy & Nemthianngai Guite

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has engulfed the world, has betrayed the informal sector migrant labour stranded all over the country. The dreams which were nurtured by the pull factors exerted by the ‘citylights’, were further fueled in the wake of ‘Jandhan’, which heralded a new chapter in the lives of the poor – with bank accounts and money in it. The ‘urban dreams’ were perhaps taking shape in their decision to move to the cities and towns for livelihoods. But, alas! the novel coronavirus, in connivance with the lackluster governance, shattered their elusive dreams.

Like in many developing countries, in India too, around 81% workers are in informal sector or work in small and medium enterprises (ILO, 2020). Workers are employed through contractors on a project basis, with no social security benefits; payment of gratuity, compensation for injury, death, maternity benefit, provident fund, health insurance and others like insurance against periods of unemployment (Coggin, 2018). Often without proper record, temporary nature of work with no minimum or equal wages and conditions of work are far from decent (BWI, 2018). The informality inevitably, leaves little scope for reliable data on earnings in the informal sector, particularly for those workers at the lower end of the labour hierarchy, including women workers (WIEGO, 2020). The supply of labour, particularly unskilled, is far in excess of the number of jobs, earnings for the majority of construction and domestic workers, which makes them vulnerable to exploitation. The unregistered construction workers, who form the bulk of the workforce, earn less than minimum wages. It is generally assumed that a family of four would require two minimum wages just to survive. About 70 per cent of unregistered construction workers do not earn enough to support even a small family (ILO, 2020). As with all informal economy workers, government regulation, national and local, or lack of regulation, affects every aspect of workers’ livelihoods, conditions of work and their fundamental rights (EAP, 2018). Therefore, perhaps the ‘junta curfew’, which spanned into lockdown subsequently, has left most of them jobless, homeless and hungry.

Resorting to the lockdown as a measure to control the present health crisis, version 1.0 was announced on 24 March. The sudden announcement and its uncertainty led to the closure of their work places rendering them jobless despite the safeguards[1]. Within days they were homeless too, no sooner did their landlords realized that their propensity to pay the rent was nil. They were on the roads, dejected and weary. Dejected with the city, which they adopted as their ‘karmabhoomi’. They were weary of the unpreparedness, which was leashed out on them in the name of controlling the health crisis. Thousands of them started walking back to their home towns. They feared the uncertainty of joblessness, homelessness and approaching hunger and humiliation. But there was hope that ‘things might improve’ once the lockdown version 1.0 ended after 21 days.

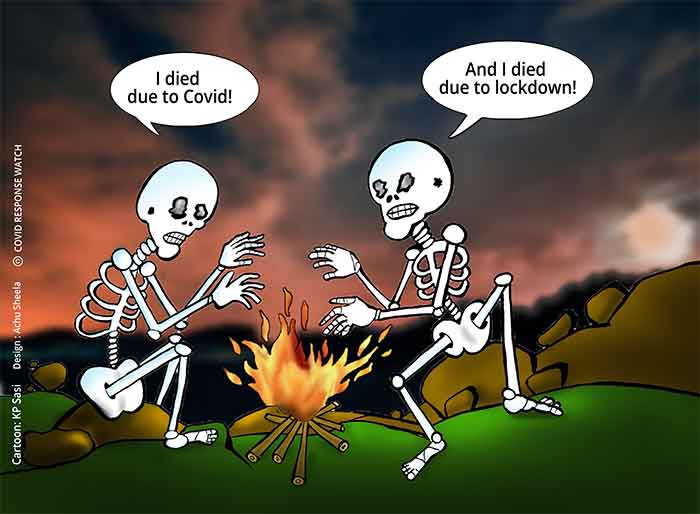

To their utter dismay, version 2.0 was announced on 14 April when the spread had taken lives of 326 persons, about 1000 had recovered. The number of confirmed cases had increased to 100024- from only one on 30 January 2020. The same day WHO cautioned the world that a public health emergency was in the making and the countries should be ready with the personal protective equipment and a strategy to address it. Perhaps, even WHO did not foresee the plight of the informal sector workers arising out of the lockdown announced without any preparation. Repeated requests were made and safety guidelines issued by the ministry to ‘stay home’ and maintain distance between persons. It made little sense to those who were already cramped in one room shanties and further rendered homeless and herded in shelters. Washing hands regularly in the absence of water and soap was certainly a luxury for them. Lockdown version 2.0 brought them on the highways, confronting the systems, to start their journey home- on foot, tucked with bundle of belongings and infants on shoulders. They were forced to do so because the shelter and food, which was provided by different agencies, including state, was inadequate. Living conditions were appalling. Above all, such a khairat -‘free food and shelter’ reduced them to beggars- from workers who earned their livelihood with dignity. Many lost their lives- not to COVID-19 but to the hunger, humiliation and exhaustion. The state was required to give them adequate support, or in its absence, allowed them to go home. Trains could have plied based on the distance and safety advisories- as it is being done now after announcing version 3.0. Certain relaxations are being considered for version 4.0.

In the states receiving and sending migrant labour, except Kerala, the number of cases increased from version 1.0 to version 2.0. Kerala responded well in addressing the pandemic and could control the spread. Kerala is also the state, which treated its labour relatively better, given the statutory ‘Kerala Labour Welfare Fund Board’ started as early as 1977 ensuring minimum wages. Despite from lower rungs, the labour in return, contributed about INR 50000 to the Chief Minister’s Relief Fund. The state too, went to the extent of not only providing them meals, but also took care in arranging the meals to suit respective regional palattes.

The fear that the number of cases will rise when the lockdown is lifted is omnipresent. This justified the extension of the lockdown ushering in version 3.0 in mid April. But how will the migrant labour be facilitated to return to their places? Who will ensure their return and how? Their work units will take time to revive. It would have been wiser to sent them home earlier. Now, when the version 3.0 which was scheduled to end on 16 May, but has led to the Verison 4.0 till 31 May, the government has started sending them home in trains- ‘shramik specials’, but at a cost. They have to pay for this service which state is obliging them with! Amazing is the ‘concern’ of the state for the helpless migrant worker. Perhaps the expenditure incurred in showering petals on the hospitals on last day of version 2.0, would have more meaningfully used for arranging food, accommodation and transportation for the stranded workers. Version 3.0 robbed them of their meagre savings, and version 4.0 will see them exhausted and perhaps infected too. It is shamefully appalling to note that the ‘vande bharat’ could be launched to bring back those stranded abroad, but nothing could be done for the ones struggling on foot to reach home, just here on the roads of the cities they toiled in, and the highways which connect them. While the ‘vande bharat’ expeditions are reported as first or second news in AIR bulletins every day, the desolate migrant workers seem to have been obliviated from the mental map of the state, despite media showing desperate images 24X7.

The lockdown has triggered indescribable suffering additionally, for the migrant women workers. With economic activities halted, women’s disadvantage in access to work will further reduce. During lockdown, there are women who have delivered babies, are fending for sick, disabled, and themselves fallen ill. They are herded in spaces, which rarely allow personal hygiene to be practiced as per the WHO advisory for the pandemic. Availability of water and toilet is questionable. Menstrual hygiene is affected most badly. In the absence of money to feed, especially if they are economically dependent, following the WHO guidelines for the use of soap is impossible. But in such conditions, expecting frequent handwashing is a misnomer, all the more when food and water is being supplied by others and mostly once a day.

Therefore, the present epidemic of the coronavirus COVID-19 is no more only a health problem. With the lockdown being projected as the only measure to combat it in the absence of a vaccine, the pandemic has moved beyond the spheres of health and health care provisioning. The lockdown has affected the economy, work, interpersonal relations, and induced psychological conditions such as stress and anxiety. The suddenness of its announcement left little space for any kind of preparedness in any sector- institutional, employment, domestic. Subsequent extensions have also been of a similar nature. It is evident from the media sources- print and visual, that the vulnerable populations have been worst affected by such decisions. People, who needed to move from one place- country, state or city, to the other, were caught stranded since the transportation system was halted. However, it also has unprecedented consequences for mobility across countries and within too. It has involved changes in controlling migration, and in the situations of migrants. Therefore, communication of such decisions by state to the people becomes extremely important.

Learning from past- need for appropriate communication

International organization like WHO, IOM, UNDP, UN Women etc. have geared up to respond to this public health emergency from a mobility perspective. Learning from the experience gained in previous emergency situations, such as the Ebola, H1N1 and SARS outbreak, for the countries is imperative. India has the expereicne of 1918 influenza, 1992 plague and dengue and the more recent NIPAH outbreak to learn from. There is a need to integrate mobility of people and health concerns across and within countries throughout the world. Communication, inevitably, becomes an important contrivance to create an enabling environment for this purpose. To ensure that mobility is taken into account in public health messages, and that migrants and mobile communities have access to timely, context-specific and correct information, various agencies- international organizations, union and state governments, local institutions, community based organizations etc. require to connect and work in consonance. If the communication regarding economic safeguard of the workers and the employers could have happened in time and appropriately, the need to travel back home would not have arisen. Dissemination of information about their safe camps, food distribution, water supply, tolet availability and other related needs remained inadequate. Even now, when the trains are expected to take them home, there is no or very little information on the paraphernalia required to register to travel home, paradoxically, in one’s own country!. The crowds at the railway stations are defying all norms of ‘disease distancing’. As the lockdown version 4.0 relaxes some mobility restrictions, there can only be hope for better information available for these desperate workers.

In India, over a short span of time, since the COVID-19 induced lockdown was announced, migrants are exposed to many vulnerabilities, far more than other citizens. ‘For this reason, working on effective communication to minimize the impact and strengthen ties with the migrant population and authorities and actors close to said population, will be a necessary baseline to face the pandemic’ (UN Migration IOM, 2020).

India started its vigil against the pandemic by screening the immigrants at the airports starting with the announcement on 4th March 2020 and started the evacuation. This was followed by the stigma and fear generated among the people- the ‘non-migrant residents’. Closure of economic activities consequent of the lockdown, resulted in unabated exodus of the migrant workers in the informal sector from the big cities to their native places. The commitment of the concerned ministry and the departments was disseminated through various modes of communication. Due to their responsibilities, it is necessary to involve and secure the commitment of the authorities to support communication activities against COVID-19 at border points, such as by disseminating information, as well as advice on prevention and when/how to seek medical care for those desirous of traveling back home. There can be posters and kiosks at the toll stations and other such junctions

With more than 42836 confirmed cases, 1389 deaths and only 1389 recovered cases on Day One of version 3.0, the spread is visible despite lockdown. As we are moving towards the end of version 3.0 and entering in the ‘relaxed’ version 4.0, the numbers of confirmed cases have surpassed that of China. As of 15 May, at 85970 confirmed cases, India has surpassed China’s 82933 by more than 3000 cases. But, India stands comparatively better than China with regards to 2752 deaths as against China’s 4633. China has 1881 more deaths than India. India’s fatality rate is around 3 percent, less than China’s 5.5 percent. But the migrant workers have borne the brunt thrice. Version 1.0 rendered them jobless and homeless, version 2.0 got them hunger and humiliation, and version 3.0 robbed them of their dignity and filled them with hopelessness- thinking of the promised ‘achche din’. Will version 4.0 do them some good and restore the hope? Good governance and its communication to the workers perhaps will.

References-

BWI (2018) Building and Woodwork International

https://www.wiego.org/resources/solidarity-building-and-woodworkers-international. Accessed on 16 May 2020

UN Migration IOM (2020): How to Focus Communication towards Migrnt during COVID-19 Outbreak’ International Organisation for Migration (IOM) https://rosanjose.iom.int/site/en/blog/how-focus-communication-towards-migrants-during-covid-19-outbreak. Accessed on 15 May 2020

WIEGO, (2020): Construction Workers. Women in Informal Employment- Globalising and Organising. http://wiego.org/informal-economy/occupational-groups/construction-workers#page-top-link .Accessed on 15 May 2020

EAP (2020):Engineers Against Poverty (www.engineersagainstpoverty.org). Accessed on 15 May 2020

Coggin,Thomas (2018): Informal Work and the Social Function of the City: A Framework for Legal Reform in the Urban Environment. WIEGO Working Paper No. 39. Manchester, UK: WIEGO. Accessed on 15 May 2020

ILO (2020): COVID-19: Labour Market Measures (India) May 14, CENTRAL GOVERNMENT Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India.

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/—sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_741923.pdf. Accessed on 12 May 2020

Bio notes

Sanghmitra S Acharya is a Professor, Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, India. She was Director, Indian Institute of Dalit Studies, New Delhi, during 2015-18. She has been a Visiting Fellow at CASS, China (2012); Ball State University, USA (2008-09) and UPPI, Manila, The Philippines (2005); East West Center, Honolulu, Hawaii (2003) and University of Botswana (1995-96). Research interest include access to health, social epidemiology, marginalization and discrimination. She is in the advisory board of many institutions including institutional research ethics boards. Her published work is in the area of health and discrimination, urban sustainability and sanitation workers.

Sunita Reddy is an anthropologist, teaching public health in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) for the past 16 years. She has contributed substantially in various social science areas of research; disasters, mother-child health, gender violence, child rights, tribal health, indigenous medicine, migrant workers, medical tourism and surrogacy. She has published widely, having three books and number of research articles/ papers in peer reviewed national and international journals and newspapers. She is a founder member of a trust ‘Anthropos India Foundation’ which engages in visual and action research. She is actively involved in a community-based organization ‘Satat’ to reach out to the rural and urban slums through its mandate which includes research and community based development activities.

Nemthianngai Guite is an Associate Professor in the Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She has also taught in the Department of Social Work, University of Delhi as an Assistant Professor for 11 years. She is a trained social worker with specialization in public health. Her research interest include Medical Pluralism; Indigenous healing systems; Global Discourses on Biodiversity and Indigenous knowledge on Medicinal plants and substances; Public Health and Social Work; Health Care Social Work Practice; Social Groups and Social Networks. Some of her distinguished international fellowship include Fulbright Nehru Post Doctoral Fellowship awarded by USIEF in 2016, and Shastri Mobility Programme awarded by SICI in 2018. She has published in national and international journals of repute and has a couple of books to her credit.

[1] Building and Other Construction Workers (regulations of Conditions Services) Act, 1996; Building and other Construction Workers Welfare Cess Act, 1996, www.labour.gov.in (Accessed on 11 May 2020

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWS LETTER