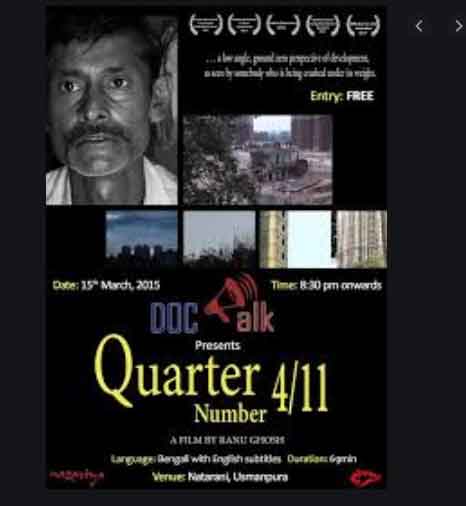

In ways more than one, Quarter Number 4/11, a documentary about demolitions and displacements and resultant miseries to a defenseless but defiant working class family, is reminiscent of Anand Patwardhan’s epic Hamara Shahar, made a quarter century earlier.

“Quarter Number 4/11 is a ground-zero perspective of urban real estate development, narrated through the plight of ex-factory worker Shambhu Prasad Singh, a victim of the development in Calcutta’s South City, eastern India’s largest mixed-use real estate development. Shot over ten years, the film is about one man’s losing fight to hold on to the ground where he was born, raised and earned his living. It is the narrative of a man who is being forced to evacuate his ground to make space for ‘development’.”

The words belong to the Calcutta documentary filmmaker Ranu Ghosh who critiques the contemporary cancer of despoliation in the name of development through the precarious life and tragic death of a Bihari worker who refused to vacate his company quarter despite threats and stark inconveniences to himself and his family. Shambhu’s father and grandfather before him had worked in the same once large and prosperous Usha Factory in the Jadavpur area of the city. Although they had some agricultural land back home, theirs was essentially a working-class family which had seen good days in an urban space.

For decades prior to its closure in the 1980s when the Left Front was in power, the factory had been making ceiling fans and sewing machines which enjoyed great popularity both at home and abroad. The ‘Usha’ brand was instantly recognizable and synonymous with dependability. But, citing militant trade unionism as deterrent to production and productivity, the Delhi-based owners of the factory pulled down its shutters, throwing hundreds of workers like Shambhu out of work. Soon after the closure, negotiations for the sale of factory land began between the owner and a conglomerate of seven powerful real-estate developers. Within the factory premises on Prince Anwar Shah Road – a familiar stretch of asphalt in Jadavpur – stood rows of quarters where the workers and their families lived. When the developers moved in, all the workers with the lone exception of Shambhu vacated the quarters where many of them had been born. Those who gave in were unable to stand the heat of threats from the new owners.

The film tells Shambhu’s and his family’s story of stout resistance against the tyranny of gigantic cranes, bulldozers, hammers and hordes of uniformed securitymen. Ranu Ghosh records the whole saga with comradely eyes in a neo-realist style of a latter-day vintage.

Quarter Number 4/11 (2011, digital, 70 minutes, Bengali and Hindi with English subtitles) shows the isolated Singh family going about their daily routine with what could only have been a show of nonchalance. Clearly, they did not wish to give a sense of victory in any way to their oppressors. Meanwhile, the viewer is left to imagine with a growing sense of disquiet the daily horrors that the family must have been subjected to, especially the mental pressures after sunset. While Shambhu took on the job of a minibus conductor to keep the home fires burning, his wife did her puja, cooked, stitched and washed, and took care of her child. The boy watches television, does his homework at night and prepares to leave for school in the morning. Ranu Ghosh enters the family spaces and records the details of the three deprived and determined lives as only a deeply involved chronicler with her head and her heart in their right places, can.

No family can do without its quota of fun, even when in the midst of dire adversity, for such is the nature of human existence. Even a family as badly cornered as Shambhu Prasad’s is unlikely to go down without a fight, once it is convinced of the enemy’s wrongdoing and the justness of its own cause. When the whole city is caught up in Durga Puja or Chhat revelries, is it possible that Shambhu’s little son, his feisty wife or the man himself will allow their flawed destiny to keep them away from the celebrations? They join in the fun, propelled forward by their big hearts and the little means at their disposal. Not all the massive instruments of intimidation at work all through the day and night around Quarter Number 4/11 can rob the Singhs of their robust engagement with life in all its abjectness, punctuated once in a long while by a few moments of carefree happiness.

Ghosh records with striking detachment many of the small happenings around the quarter or inside it, even as the viewer has the growing feeling that the besieged dwelling’s days are numbered. The filmmaker is, of course, involved in the family’s destiny, but not in any overt way. The film’s dramatic structure takes on the look of an authentic thriller precisely on account of the distance that Ghosh has decided to keep between herself (the detective), those under her scrutiny (the pursued), and the largely invisible sinister pursuer.

Sometime after the commencement of shooting, there comes the dreaded moment when the filmmaker is warned to keep off the huge site where the construction of a shopping mall and a sheaf of multi-storied buildings is in progress. But Ghosh is not to be fettered. She passes on a digital camera to Shambhu along with an elementary course on how to use it. From then on, Shambhu takes to shooting those spaces in his life entry to which is denied to Ghosh. From a worker in the painting division of the erstwhile Usha Fan Factory, Shambhu Prasad Singh becomes a home-grown cinematographer, not out of inclination but out of necessity; a subaltern artist is hewn out of the hard rock of adversity combined with a desperate will to record for posterity a few facts about an oppressed but undaunted Indian family. It stands to Ranu Ghosh’s credit that when the credits start rolling at the end of the film, she shares the honours for camera with Shambhu, in fact placing his name before her own.

In one of the more heartening passages in the film, the viewer travels with Ghosh and the Singhs to their village home and family acres. Shambhu’s retired father and his mother, especially the mother, dote on him. They cannot bring themselves to accept the undeserved fate that has befallen their son. They approve of Shambhu’s decision to fight his case in court. Both are full of love for Shambhu, but he appears to be more attached to his mother who he takes into his firm embrace in full view of the camera. She cautions him against evil elements in the big city, but also encourages him to continue with his battle for his rights and for his dignity. Fondly, the camera takes in the family exchanges, interior and exterior views of the modest family dwelling, and the nearby fields where crops are grown. All-in-all a rural idyll of family togetherness lasting for a short while is drawn. The spell is, however, broken once the family is back in Kolkata, which had once been a bastion of working-class struggle and solidarity but is now reduced by time and circumstances to a pale shadow of its former self.

This change pains workers like Shambhu deeply, which comes across sharply in one sequence showing him having a drink with some of his former colleagues who, unlike him, appear to have made peace with their conscience and the shrinking world around them. Shambhu records the drinking session with the digital camera given him to use. He gives vent to his frustration at having been abandoned by his friends or the Union people in more words than he has so far been shown using to express himself. Hard words are exchanged, decibels rise, the distance that has crept into their relationship is underlined.

Visually, the passage is as exciting as it can get. The uncertain quality of sound or image is in sharp contrast to the polish associated with the work of a trained and experienced hand like Ghosh. The earthy aesthetics ingrained in Shambhu’s cinematography do more than ordinary justice to the fear and frustration in the lives of those fractured people portrayed in the film, but none more fractured than the hapless Singhs. In a sense, Shambhu’s untutored camera – strangely, all the more effective for being untutored – is a tribute to the inventiveness of Ranu Ghosh’s evolved camera-mind.

The sequence showing the man getting ready for sleep underscores not just his personal struggle but the uncertain status of the class to which he belongs – the “hewers of wood” without wood to hew and the “drawers of water” without water to draw. Perhaps, a more bitter irony of workers galore but no work available to them, is difficult to visualise! Shambhu does his present job not because he likes it, but because no work of less strain and better pay is available to him.

But that sequence – we realise after the film is over – held in it the premonition of what finally happened to the brave luckless fellow. In the midst of his fight against the might of organised capital and the dwindling will of labour, Shambhu Prasad Singh met with a violent end in what was said to be a road accident. The suspicion still lingers that there was an invisible hand behind the death. The film does not tell us what happened to Shambhu’s wife and son, leaving the viewer to assume that they returned to their native village in Bihar to nurse their wounds away from the public eye.

Cesare Zavattini, whose ideas about cinema, society and politics were greatly responsible for the birth of Italian neo-realism after World War II was over, would have been happy with, and deeply disturbed by a film like the one under review. One is reminded of Zavattini’s words: “I want to meet the real protagonist of everyday life, I want to see how he is made, if he has a moustache or not, if he is tall or short, I want to see his eyes, and I want to speak to him.” In a strange sequence of events, by turns ordinary and unforgettable but never boring, Ranu Ghosh resurrects before our eyes ‘a real protagonist of everyday life’ and makes it possible for us ‘to speak to him’ about his past and his present, and perhaps, through his experience, about our own future in the face of the onward march of big capital and the conspicuous absence of heart, mind, muscle and conscience on the part of lesser protagonists of everyday life, even lesser than Shambhu Prasad Singh.

Ghosh also introduces us at length to the real protagonist’s immediate and extended family which provided the necessary love and understanding on which Shambhu’s fearlessness rested. She also lets us into a severely restricted space of two small rooms and a balcony where we watch in awe the blossoming of an artist with a strange toy in his hands, the like of which he has perhaps never seen, let alone held before. Is it possible that our protagonist had imagined to himself, that one day the world would come to recognise him or to know him better through the doings in light or in dark that he had recorded with that strange, democratic toy?

( Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.)

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER