In ‘La Strada’ and ‘Nights of Cabiria’, Fellini’s boundless formal and narrative energy is married to his profound humanism

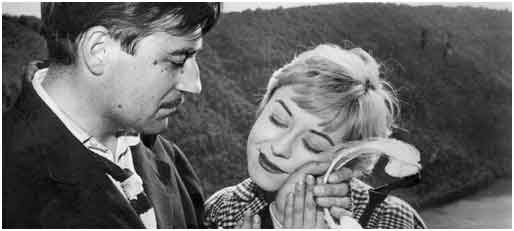

A still from ‘La Strada’ (1954)

To most cinephiles, Federico Fellini’s reputation rests on his triple masterpieces from the 1960s and early 1970s– La Dolce Vita (1960), 8 ½(1963) and Amarcord (1973). Each of these later films is a tour de force of fantasy, dreams, and extravagant flights of imagination. Watching these intensely idiosyncratic creations, it is easy to forget that Fellini’s roots as a filmmaker lay deep in the Italian neorealism of the 1940s and the immediate post-war years. He had begun his career in films by writing the script for Roberto Rosselini’s neorealist classic Rome, Open City (1945), following it up as Assistant Director on Rosselini’s next offering, Paisan (1946). Fellini’s first directorial venture – Variety Lights (1950) – was also in collaboration with another major neorealist, Alberto Lattuada. Italian neorealism typically foregrounded a world which was bare, desolate, severe – very far removed from the romantic ancient ruins, scenic old churches and lively city streets teeming with gay holidaymakers which were the staple of lavishly-mounted extravaganzas like Roman Holiday (1953). The neorealist canvas is populated by men and women scraping a living on the big city’s margins; empty night-time piazzas, bored layabouts and windswept, deserted beaches feature here more often than not. Its cheerless landscape rarely lights up with the hope of redemption. Though Fellini’s was too original a talent to be pigeonholed, his neorealist beginnings have shaped at least two of his early classics, La Strada (1954) and Nights of Cabiria (1957). Sadly, these two films often lose out on viewer as well as critical attention. The hundredth year of Fellini’s birth is as good a time as any to look back on these two little gems.

La Strada (meaning ‘the road’) tells the story of Gelsomina, a young woman who is sold by her poor mother to Zampano, a coarse and brutish one-trick travelling performer. The naive, utterly worldly-unwise Gelsomina is completely defenceless against the harsh and pitiless world she has been tossed into. She does her best to please Zampano– to whom she is cook and concubine, besides handling the drumroll and clown routines at his street performances — though she resents the way Zampano abuses her often, or takes up with any woman who happens to take his fancy. She runs away, but inevitably Zampano traces her back. On the road, they make the acquaintance of an itinerant circus, and Zampano joins the troupe as a performer. Il Matoo, the circus’s sprightly clown-cum-high-wire walker, charms Gelsomina with his restless energy and ringing laughter. Il Matoo teases the boorish Zampano relentlessly, and one day the infuriated Zampano kills him in a fit of frenzy. The death affects Gelomina deeply, and she begins to sink into catatonic depression. Zampano tries to shake her out of it, but when he fails, he abandons Gelsomina to her fate and moves on. Some years later, in a chance meeting with a woman who had known Gelsomina briefly as she wandered about the countryside all alone, Zampano comes to hear of Gelsomina’s death. Remorse consumes him, and, perhaps for the first time in his life, he feels utterly forlorn.

The story-line is simple, even thin, because, in La Strada, Fellini was essentially concerned with a moral or spiritual ambience, and a highly evolved dramatic structure might, he felt, only undermine the film’s tonal unity. In this, La Strada is not unlike a parable, or moral fable. Many of the trademark visual motifs a Fellini aficionado associates with him – the circus, religious pageantry, the Fool, a snow-bound landscape and, of course, the sea – pass unhurriedly through the film’s canvas, each component helping keep alive a sense of anticipation, which sometimes turns into foreboding. Clearly, grinding poverty, greed, jealousy, cruelty – features of a society ravaged by war— have scarred many of the film’s protagonists, but Fellini is never judgemental. Even big bad Zampano is not denied his basic humanity. When, after the clown’s death, Gelsomina sinks steadily into gloomy immobility and drifts apart from Zampano, he is clearly touched by her misery, though he hardly knows how to show her his concern. In his own rough way, he tries to feed and care for her, but is repulsed by the depth of her depression. In an episode that burns into the viewer’s memory, when Zampano abandons Gelsomina as she sleeps by the roadside in the midst of wintry desolation, he covers her in a warm blanket, and leaves some food for her. Then, as he prepares to slink away on his ramshackle caravan, he remembers the old, battered trumpet which he had taught Gelsomina to play a little and to which she had grown greatly attached. He tiptoes back, places the instrument at her feet and walks away. The whole sequence is bathed in a tenderness which it was quite hard to associate with Zampano till that point. There is just a hint that perhaps he had come to love Gelsomina, but never knew it himself, for he knew not what love was.

Zampano and Gelsomina in a still from La Strada

But of course La Strada is pivoted on the round-faced, wide-eyed, guileless Gelsomina who looks at the world around her with complete bemusement, but also great compassion. Not until the end does her easy, childlike optimism ever desert her either. She has an incredibly mobile face, and can smile through her bitterest tears. With her oversized coat, bowler hat and bobbing footsteps, if she looks rather like Chaplin, it cannot have been unintended. Like the tramp, she has an infinite capacity for joy and wonder. And like the tramp, again, she can make the line, separating gut-wrenching pathos and the preposterously funny, look very thin. Indeed, Chaplin himself was so taken with the work of Giulietta Masina, the actor (also Fellini’s wife) who played Gelsomina, that he singled her out as “the actress I admire most”. Anthony Quinn as Zampano and Richard Basehart as Il Matoo, the clown, also put in wonderful performances, but inevitably, Masina puts them somewhat in the shade. Nino Rota’s hauntingly beautiful background score is another of La Strada’s highlights. The film won Fellini a Silver Lion at Venice, and in 1956, it won the inaugural Oscar for the Best Foreign Language film.

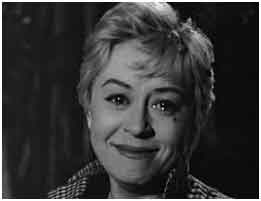

A still from Nights of Cabiria (1957)

Giulietta Masina is a live wire in Nights of Cabiria – the 1957 film about a feisty, scrappy, low-end prostitute who walks postwar Rome’s shadowy, gloomy streets armed with her high spirits, a sharp tongue, and not much else. She believes she is a shrewd judge of men, but is essentially naive. Deep inside her, she pines for love and this, together with the fact that she implicitly trusts others, proves to be her undoing again and again. A lover whom she had been pampering with expensive gifts pushes her into the river and decamps with her purse containing 40,000 lira. A magician whose show she had gone to attend summons her to the stage, hypnotizes her, and lays bare her soul – with her vulnerabilities — to the audience, who deeply humiliate her by laughing at her uproariously. A quiet, timid bachelor accosts her, and woos her over many days, slowly chipping away at her power of judgement and her mistrust of suitors. He claims he respects Cabiria’s independence of mind and suggests they were made for each other. His calm and understated manner finally manages to break down Cabiria’s emotional defences. She agrees to marry him. Cabiria sells off her house, of which she is decidedly proud, also her other belongings, closes her bank account, and brings in a handsome dowry of 700,000 lira, though the man never seemed to ask for anything. She bids farewell to her streetwalking friends one last time and proceeds to meet her husband and hand him her life’s savings. The man walks her through a wood to the edge of a ravine with a deep river. Cabiria grows uneasy, and begins asking him what he had in mind, joking that she hoped he was not about to push her into the river. Then a look into his eyes tells her he had planned to do just that. She breaks down, sobbing inconsolably, even as the man grasps at her purse and runs away with all her money. She is too stricken with heartbreak to care.

Once again a slight, very nearly flimsy, plot, but Fellini pulls off a cinematic triumph all the same. Cabiria effortlessly glides over a stunning spectrum of emotions: fear, rage, helplessness, faith and defiance. Nights of Cabiria also has its fair share of religious processions, tableaus, showmanship and magic. And of course of tumbledown shacks standing sadly in the middle of an urban wasteland. Cabiria’s proud house is an ugly little jerry-built structure situated at the far end of this same wasteland. With her waiflike innocence, she carries herself through Rome’s gutters, and, miraculously, her inner being seems capable of shrugging off all the muck and filth surrounding her. When she goes to a religious procession, she hopes Virgin Mary will be able to redeem her life, but when nothing seems to happen, she cries out that it was all a hoax. And in the film’s unforgettable finale, as she stumbles on her long, weary walk home after her final heartbreak, a band of travelling musicians passes her by, playing their soulful music. Instinctively, Cabiria warms up to the music. A smile begins to break out on her drawn, teary face. This is perhaps the closest that Fellini comes to tragedy, but a heart-warming tone of redemption is yet heard here. The film won the 1957 Oscar for Best Foreign Language film, while Giulietta Masina won the Best Actress award at Cannes that year.

Masina smiles through her tears in Nights of Cabiria

Fellini was to craft dazzlingly beautiful film narratives in later years, narratives which redefined both what movies could be about and also how they could go about representing reality. Even though some of his signature motifs stayed with him till the end, his work from La Dolce Vita onwards increasingly shed its rugged, gritty look of the 1950s, even as they shifted focus to the heart of the bustling big city. And while his later films are justly celebrated for their heady brew of fantasy, wit and dreams, the low-key lyricism of the earlier period, coupled with his deep compassion for insignificant women and men living on the fringes of the good life, make La Strada and Nights of Cabiria memorable artistic experiences.

Anjan Basu can be reached at [email protected]

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER