“Of course it is … impossible until it is done.”

Daniel K. Young, A House Divided, 139.

As a white person, I realized I had been taught about racism as something that puts others at a disadvantage, but had been taught not to see one of its corollary aspects, white privilege, which puts me at an advantage.

Peggy McIntosh, White Privilege, 189.

The year 2011 heralded in the end of sexism—an embarrassing, nasty, cultural oversight we had grown accustomed to for a long time during which most of us viewed women as a “sometime thing.” What mattered to us then, and still does to a lesser degree now, is that we have paid attention only to their appearance, countenance, smile, and display. That they should have emotions, self-esteem, and even ego was out of the question. The whole idea of proffering due respect to them was anathema to many of us. All that came to an abrupt end with the much-publicized arrest of Dominique Strauss-Khan, the then head of the International Monetary Fund, a man presumed to run for high office in France in 2012, which opened the gate to review many other cases of sexual assault. It also paved the way for the birth of the #MeToo Movement, which brought about other trials and therefore imprisonments of some powerful men reputed to be sexual predators: Tarek Ramadan, Jeffrey Epstein, Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein, to name but a few. As we later learned from the hearings, DSK had to face not only the charge of sadism but contend with an unyielding and rigid American puritanism, which had no patience for le droit de cuissage à la française! The guilty verdict against a white man who sexually abused a black woman, Nafissatou Diallo, was swift and to the point. Suddenly, the head of the IMF was not worth a tinker’s cuss. This is not France where l’amour, toujours l’amour and voulez-vous coucher avec moi, ce soir are common currency. In Protestant America, there is an outside chance that rigid austerity in conduct and morals is de rigueur. Seen from the exterior, refusing to adhere to such conduct will cost you dearly. It did Mike Tyson, Bill Clinton, Woody Allen, Gary Hart, Roman Polanski, among many others. Austere as it is, the very idea of purity in America is steeped in hypocrisy, plotting, and deceit, perhaps without knowing it. Donald Trump is the exemplar of all three. Unable to control his libido, he continues to use and abuse women whom he considers mere objects of desire. His association with Ghislaine Maxwell and the late Jeffrey Epstein is nothing more than the tip of the iceberg in a saga marked by a lewd revelry that went on unchecked for many years. A modern-day Caligula, Trump may never answer for the random violence he has inflicted on the young and not so young women who crossed his path. Today, merely to look at him must send shivers down their spines.

The lesson that ensued from the rise of the #MeToo Movement has taught us that, henceforth, there must be no victimization of women by powerful men. Can the same be said about black people, who have been persecuted, diminished, and exploited for a long time? Can we at all equate white lives with black lives and, as it happens, aren’t black lives depreciated every day while white lives suffer from a surplus of value, which tips the scales into white supremacy? Does race, an artificial construct invented by white men to undermine others, make a difference between people? For now at least, black lives are misprized and unless we reach the point where all lives do matter, they must first accomplish parity by signifying something. None of the above is beyond our comprehension if we try. All we need to do is make an effort. In consequence, it remains an open question whether racism can be put to the same test that sexism underwent. The parallel is urgent. For the intention and method of the uprisings in America and elsewhere, following the brutal killing of George Floyd, are meant to lead us to a time when we are able to imagine all people, regardless of color and/or gender, living life in harmony with one another while being governed by the same laws under the banner of no racial and/or sexual notability. In the same vein, can racism, which really is a cocktail of prejudice and power, a kind of guild where a certain ideology thrives and where the “members go through life accepting the benefits of membership,” as Noel Ignatiev would have it, “without thinking about the cost” to the rest of us; in fine, can a system, rather than a slur, exist without “white privilege” as an accomplice to the crime? No need to dwell here on the avalanche of racist sewage strewn with abuse, resentment, and hate that heads in the direction of black people every time they stand up for their rights. In this wrought-iron world of crisscross cause and effect, could it be that racism, which has been a constant hindrance to normal relations between what Trump calls “us” and “them,” is a structure of pernicious social hierarchy between people, positioned according to the way it is perceived and tied in knots to a so-called heredity?

Priyamvada Gopal attempts an answer: “One distinctive feature of whiteness as ideology is that it can make itself invisible and thereby make its operation more lethal and harder to challenge.” A vein of truth runs through her argument, which joins the one made by Ignatief sometime ago, and which seeks not to suppress white people altogether but to abolish “a system of racial entitlement that necessarily relied on the exclusion of those deemed to be lesser.” In a similar vein, Gopal writes to tell us that

[w]hiteness is not a biological category so much as a set of ideas and practices about race that has emerged from a bedrock of white supremacy, itself the legacy of empire and slavery. Confronting the idea of whiteness involves far more uncomfortable discussions than ‘inclusion,’ especially for people deemed white, since it involves self-examination and acknowledging ugly truth, both historical and contemporary. It is simply easier to try to shut it out or down.

This is no jejune point that Gopal makes. It is passionate, energetic, and insightful. It also chimes with the rising tide of public anger against those who adhere to the credo of whiteness. It tells us in so many ways that the claim which says that black lives need to matter more than they have in the past, that they should be given more onus and value, is justified. “Until we square up to the ugly realities of how whiteness operates—lethally,” Gopal perceptively adds, “invisibly, powerfully—we are doomed to fighting a toxic and pointless culture war, where the only winners are those who want hatred to prevail.” What Gopal advocates is indeed to the point, but she somehow fails to note how racism is an oxygen bottle the white system has been brought up on. It consists of advantages and disadvantages, setting up an immense iceberg, the signs of which, verbal and physical violence (of the letter), are only the tip that emerges from the fog. The very tenet “white privilege,” propelled anew to center stage by the recent demonstrations against police violence toward black people, points to all the social advantages, which benefit the persons who are not the target of racism. It shows how it has become almost a kind of instinct; one that falls within a set of social relations i.e. connections between social groups, some of whom are boxed in while others are aided by the many social hierarchies that protect them regardless of what they do. The verity of the point I am making here is nowhere more obvious than in the treatment afforded Prince Andrew after it was discovered that he had been involved in the Epstein connection, yet he is still at large in spite of the wrongs he inflicted on very young teenage girls in orgies that took place in New York, Paris, and St. James Island, in the US Virgin Islands, a property owned by the late Epstein himself. Bill Cosby, on the other hand, when found guilty of sexual misconduct, was sent to jail where he will probably rot for the rest of his life. The presence of inequality supposes then, in all logic, the presence of prerogative. That being the case, to say that “white privilege” does not exist in the West amounts to strictly declaring that racism is not alive and well. To pretend that only the second is present conveys either a superficial reading of the adage, reducing it to the principal of legal franchise, or a narrow understanding of racism.

Stemming from the struggle against racism, the maxim was popularized by Peggy McIntosh in White Privilege and Male Privilege (1989), in which she lists the daily “small things” that are pretty obvious for a white person to undertake but can be problematic, if not impossible, for a black or brown person to take on: switching the television and watching persons with whom it is easy to identify; moving into a new neighborhood without fretting about what kind of reception you and your family will get when you arrive; not worrying about the presence of the police in the vicinity where your children will play; in fine, you are welcomed in. Ever since it came about, “white privilege” has become even more relevant under Trumpism when we consider it within the present tense context. Gopal explains:

The truth is that there is nothing pleasant about confronting the reality of an acute racial hierarchy. If the racial order is really to change—and there are those who don’t want it to—it is not just black lives or racial minorities that should be the topic of discussion, but the racial ideology that currently calls the shots in western societies.

The case that Gopal makes out leads us to make the following expostulation. Surely, America, and say, France, have different histories. The US is a country built upon slavery, a place where racial segregation was constitutionally abolished only in 1968 whereas we know, fully well, that black people have been around for more than 400 years. France, on the other hand, a once colonial empire, second only to Great Britain in its quest to propagate its mission civilisatrice around the world, with its Outre-Mer possessions: Martinique, Guadeloupe, La Réunion—to mention only a handful, still views itself as an empire, even as La République continues to distinguish between its citizens in La Métropole and those who reside in La Banlieue and/or in far-flung lands. The best example that comes to mind is Mayotte, an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, which remains to this day, a département of France that is left to its own demise of hunger, violence, illiteracy, and now SARS-CoV-2, which has claimed the lives of so many people, who endure suffering and extreme poverty. The French Government continues to be in total neglect of, and indeed denial about, the development of the island while at the same time claiming that it is part and parcel of La Belle France.

As regards equality (of race), one can theorize that the same way we awoke to our responsibility and faced sexual wrongdoing, we must also become conscious of the fact that only another stirring (of interest) can shake us from our ignorance to the plight of black people. Such an excitement into action hinges on worldly mobilization as witness the massive revolts across the planet. More than ever, they show us how people of all colors are intensely involved in the critical period we all live in. Their breadth of tone is a living testimony to the tenacity of the downtrodden, who have long languished to engage in a radical change that takes into account all the pain black people have so far suffered. They dig deep into the annals of slavery, colonial heritage, and systemic racism. Concepts like “racialism,” “state racism,” “colonial thinking,” “white privilege” dot the landscape of their language. The debate over the various formulae has a tendency to generate a passionate controversy over whether we should denounce the idea of “racialization” and indeed “universalization.” In the meantime, the political vocabulary the new militants use refers to an evolution in the concept of racism itself, which, like the master’s house, must be dismantled at all cost. The traditional antiracist movements, whether they be the International League against Racism and Antisemitism (LICRA), SOS Racism or the NACCP, champion an individual and moral design of racism. Called “Truth for Adama” in France and/or “Color for Change” in the US, the committees accuse the state, its police force, its administration, and, indeed, its school system to unequally distribute high and low positions in the workplace and the many riches of all sorts of commodities while pretending that there is no racism in their ways of doing things. This political antiracism stand refers us to Fanon, who in 1956, impugned that the “habit to consider racism as a disposition of the mind, a psychological defect” is a mistake; it is rather a matter of “disposition enrolled in a determined system,” he wrote. This is, more than sixty years later, what young “racialized” groups are proclaiming out loud. They contend being subjected to a diffuse, always discreet, systemic racism at school, in the work place, and in the street where they live as in their relations to the police, a reality “white people” are not even aware of. It is for this reason that they sometimes plead for “non-mixed” gatherings.

Now, in perusing what follows, the reader should bear in mind what I present here is what we all know about the brutal killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. To a greater or lesser degree, his most foul murder has established a kind of poetics of justice. The heinous act did not just trigger countrywide outcries in America but in the rest of the world as well. A few examples: in the UK alone, the toppling of a statue of a 17th-century slave trader in Bristol and the daub of graffiti on a statue of Winston Churchill, a white supremacist avant la lettre, in London are quite telling. This is the very same Churchill who, in addressing the fate of indigenous peoples in Australia and America, said: “I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher-grade race, a worldly, wise race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.” The case for the defense of Churchill as a racist and land grabber is best articulated by another no less disparaging Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, who had this to add: “Churchill saved this country [i.e. Great Britain]—and the whole of Europe—from fascist and racist tyranny.” To counterbalance the claim, the South-African-American comedian, Trevor Noah, has a different take on the issue: “The bubonic plague was a major event in history, but we don’t go around putting up statues of rats.” Spot on, insofar as Johnson and Co. “pay homage to hate, not to heritage,” as Nancy Pelosi put it in a silver-tongued tone. They do not give a toss about anything except their super-inflated egos and self-fashioning.

Thanks to Roland Barthes, we know only too well that the function of mythology is to guard us against history. All at once, we are au courant of the fact that it is absurd to throw back racism across the Atlantic (what France did following the recent riots that took place in Paris remembering the murder of Adama Traoré in 2016). After all, France was an active participant in the Atlantic Slave Trade, which was one of the largest and most sophisticated maritime commercial ventures that saw more than ten million black people transported from Africa to the new world. They were marooned to work on sugar, tobacco, cotton, and coffee plantations; in gold and silver mines, in houses as servants or in rice fields as laborers. It flies in the face of common sense to think that France, like Great Britain, Portugal, Holland, Spain, does not bear a heavy responsibility in the enslavement of black and brown people: from Algeria, the jewel in the French crown, to Madagascar, where corvée labor on French-run plantations ran amok. The French like to point the finger at America and/or Great Britain when it comes to racism while at the same time claiming innocence for themselves. They are knee-deep in the same unfathomably cruel act. To this day France refuses to come to terms with its shady and stained past. In point of fact, it continues to think of itself as an empire of sorts while miserably failing its minorities, as an opinion poll, conducted at the end of 2017, concluded that “less than 1% of the managers of the CAC 40 and SBF 120 companies are French of non-European origin. Since then, the situation has not improved, in order to offer a positive image of diversity to French society,” Laetitia Hélouet, co-president of the XXIst Century Club, which was created in 2004, informs us. In 2018, the club put out a yearbook of influential people issued from La Banlieue, who, given the chance, can become independent managers. “It barely worked. It is a C-average performance,” Hélouet added in dismay while promising to make an effort to meet the challenge with a buoyed up version. Let me retain for a moment that idea in all its fateful detail because it leaves us dumbfounded as well as incapable of explaining the move the French National Assembly made when it legislated on the standing of people of mixed races and assigned a special legal status to the French Muslims of Algeria, otherwise known as Harkis, who, nearly seventy years after they sided with France in the Algerian war of independence, are still outcasts. To this day, they are social outcasts. The bitter reality of exclusion is also reflected in the homogeneity of the parliament, where we fail to find a single member of Arab descent, knowing that there are six millions Arabs living, working, and paying their taxes in France.

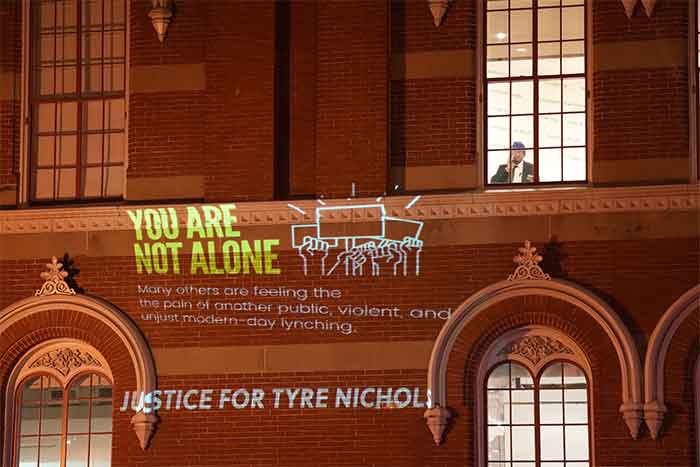

The answer to the question of race is tied to the deep anxiety neurosis white people feel every time they come face to face with their own predicament. They do so when they look anxiously at their color and realize that their “faces are not their fates.” Hanif Kureishi, who taught us a lot about ostracism, goes further in maintaining that the “… truth is that white people must be afraid. In their hearts they know it is only class, race, and privilege keeping a lot of them in position. In a real competition these mediocrities would go nowhere. In a meritocracy they’d be sweeping the floor, as the immigrants do, if they were lucky.” Kureishi is ecstatic to see the trend of events today. “It was unforgettable,” he notes, the “faces of all of those people, no longer only puppets of the market, fighting injustice and making the future. If they ask what we want, say: only the future.” Put differently, to set the pace, we must press on with the matter at hand as well as acknowledge how traumatic the infliction of racism is and how white people tremble at the thought of dealing with it. A case in point is the bill to reform the police, which Nancy Pelosi and Co. introduced and passed in the lower chamber but which was rejected in the upper chamber because of the cowardly conduct of a certain dipping donkey named Mitch McConnell and his white gang, who have already forgotten how George Floyd died. They do not really care. That George should call for his mother before he was strangled by a white policeman does not mean a thing to them. The last words he struggled to utter at least twenty times before he expired as we are finding out remind us of the nightmare scenario that these very same words could have been read out by Adama Traoré, a young man killed by French police in Paris. The demonstrations we are witnessing around the world do not speak only of George Floyd but of the many other Floyds in the West and the Rest. (Think of the cruel treatments of the Muslim, Christian, Sikh, and Low-Cast Dalits minorities in India, the Uighurs in concentration camps in Xinjiang province in China, the Rohingya people in Myanmar, and the case will be clear enough). Therefore, it is not a matter of importing a set of problems from America, as one French minister put it. In fact, the happenings in America are a catalyst in that the transatlantic mirror sends an image to old Europe and possibly the remainder of the world, where it all began more than 400 years ago when whitey embarked on a willful exchange of commodities, which included humans. Cornel West put it eloquently: the violence against poor black people wherever they are “is a lynching at the highest level—nobody can deny it.” True indeed, insofar as we are faced with the total collapse of the social experiment everywhere, be it the melting pot in America, multiculturalism in Great Britain, or Mosaic in France. It is unable to deliver any kind of nourishment for the soul. The precious poor, whether they be black or brown, are left stranded while a handsome boy resides in the Élysée Palace, a pompous Brexiteer lodges in Number 10 Downing Street, a lowlife gangster sits in the so-called White House; a stately residence that was built by the slaves, who were not paid for their hard labor whereas their masters cashed in $130 each on their backs. This is how Kureishi sees it:

What is usually left out of accounts of racism is the enjoyment it gives to those dishing it out—that hit of power and privilege, so easily obtained, telling the other who is boss, who would want to give that up-? My father and his family, who came to the west, were soon aware that the white master wanted it both ways, to use immigrant labor to build their economy, and to enjoy their share of colonialism—racism. To do that, we had to stay in our assigned place and acknowledge that nothing is deeper than skin. But that is over.

Is it really? While Kureishi’s words set us wondering, we question the present and worry about the future as we marvel at how the shepherds wonder at the angels! For now, though, the struggle must go on until we cross the white line.

At this juncture in history, there is a redemption of sorts in watching young white people stand shoulder to shoulder with black and brown and everything in between to fight back with a vengeance. “It takes a lot of effort to make the future,” Kureishi adds. “One or even several demonstrations will not achieve that. The effect will be cumulative. Some things are now impossible, and other things have become possible. And so this moment of economic breakdown and capitalistic stagnation, when neo-liberalism is destroying the very ground on which it is built, is an opportunity.” Spot on! To a large extent, the disruptive and carnivalesque mobilization against all racisms—economic, urban, social, educational, environmental, emotional, moral—reminds us of all the trappings of a merry fair. It is so because the racial fracture is mutating: we notice the togetherness of people of all colors, genders, and sexual orientation demonstrating for one cause—namely, to mark a stand for equality and justice for all. Viewed from this angle, white youth is more than a simple ally. For them, racism is no longer a matter that concerns only racialized people. It has to do with all of us together. As a result, the convergence of young people on the streets of America and Europe has dealt a serious blow to old white hegemony represented by Trump and Co. It is a step in the right direction. The anonymous England-based street artist Banksy put it perceptively: “The system is a white system.” Therefore, “. . . it is a white problem.” Indeed, for unless the US takes the question of racism to heart, black people will continue to endure marginalization, demeaning, and at times, killing, as it happened in broad daylight when Rayshard Brooks, another black man, whose sin lay in having a couple of extra drinks and falling asleep in his car in front of a restaurant, resisted arrest.

America has had a long history of violence (we still recall 1968), during which the country acquired an exquisite taste for death. A case in point: at the beginning of the last century, people took pictures of lynched and/or hanged black people, especially in the South. Later, the photographs were used to make postcards that both torturers and witnesses sent to their families in far-flung lands. In France, postcards were made of “scènes et types”—a derogatory formula that described indigenous poor people, Algerians in particular, riding donkeys or mules. Largely documented, this abject endeavor was an everyday practice. In the Wild West, photographs that exhibited corpses of “outlaws” and “Indians” were also highly prized. Recently, the images of Rodney King, badly beaten up in Los Angeles in 1991, or George Floyd strangled in Minneapolis in 2020 by a white policeman while three other officers watched without lifting a finger, fall within the scope of an American tradition that has a love-affair with showcasing the spectacle of murder. Another effect that goes back in time has to do with white systemic racism, which runs through a number of acts of cruelty, even if in America police violence does not limit itself to the question of race. In point of fact, the entire American practice of the police rests on the micro-physics of a brutality that strikes whomever finds himself or herself in the wrong place at the wrong time, but especially people of color. In the US, “police forces” or “well-organized militias,” [the expression, which comes from the Second Amendment of the Constitution, authorizes the bearing of arms in the name of security] have always been trigger happy. The massive circulation of gruesome images, which no longer emanate from torturers, hangmen, and headsmen, showing these executions, is not novel. It is as old as apple pie. Yet, we notice at least two huge differences between past practices and present-day ones. First, the exhibition of violent death was, not long ago, organized mostly by the executioners, propagandists of themselves, proud of their dirty work. This attitude lives on in the actions of the marines who were deployed in Afghanistan in 2011; they chose to immortalize their triumph by filming themselves urinating on the bodies of the Talibans, whom they had killed. However, the best part of it is that these videos are not the work of the guilty fellows who took them. They are, in fact, made to generate money for the sadists who authored them in the first place. It is, of course, nauseating that such viewings arouse feelings of celebration in the minds of the perpetrators. Be that as it may, this revulsion is accompanied by a morbid fascination for the spectacle of massacre. Second, giant social media de facto market these images of death, taken by a cell phone or a surveillance camera. They legalize, so to speak, the old underground market of snuff movies (clandestine films staging violence going all the way to murder) and so draw an indirect big profit. The plot is always moving breathlessly onward. Acting against the wishes, and indeed, the petitions issued by the Floyds, the nine minutes of George’s agony will be continually broadcast to the four corners of the world for many years to come.

To be entrenched in the view that racism runs deep in America is to be reminded of what happened on June 15, 1920 in Duluth (Minnesota) when three black circus workers: Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, were lynched in front of a cheering crowd by a raving white mob with no intervention by police. Their crime was their blackness and all the other aspects of identity that marked them as African-American. As usual, they were falsely accused of holding a white woman at gun point and sexually assaulting her, which was a canard. Poetic justice has it that on June 12, 2020, a century later, the Department of Justice granted a posthumous pardon to Max Mason, another circus black worker, who was accused of raping 18-year-old Irene Tusken. There was, of course, no evidence to support the claim, as arrived at by a family doctor who examined her and found no signs whatsoever of physical violence. Mason, the first black man to have benefitted from a long overdue pardon in the State of Minnesota, died in 1942 after spending 30 years in jail for a crime he never committed. “He would have never been condemned if he were white,” had estimated at the time a local attorney in the name of Mason Forbes, who is cited in the request for pardon, which was filed by Duluth activist Jordon Moses. Today, his proven innocence is a landmark in the pinnacle of our perseverance in a country that is ripped apart by demonstrations denouncing all kinds of racism that are still eating up large segments of the population. When an event (i.e. the late pardon) like this one happens, one finds oneself at cross-purposes with a certain reality on the ground because on the one hand it is difficult to deal with it and impossible to remain silent on the other. It is in this sense that we have to look into the present or else we cannot understand the past. If our world is in turmoil today it is because we have failed to address the grievances that a good section of the population has had against whitey. As a result, every country in the West, and America in particular, has been forced to take a hard look at itself in the mirror as well as revisit its past in relation to the question (of race) posed by the present. The masses of all colors who have joined forces to scream with pain since the death of George Floyd are asking us not only to put an end to systemic racism but also to deal once and for all with violence and discrimination against the black community. After all, the marginalization of all those people who are not white is the product of a prejudice that is rooted in the past and maintained in the present; the end-result of a practice that was not corrected at the outset; the part of a question that was never dealt with in the first place. All these shortcomings have coalesced to give birth to an untenable situation. In order to answer the call, we need both justice and reparation. We also root for new symbols that carry a rainbow meaning intent on including all of us in the many-windowed house. Such an effort can heal the wounds of the past as well as inspire us to dress the wounds of the present.

We all agree that resorting to violence does not do any good. But what are we do when the only course of action is clashing with a sadist president and/or police whose dehumanization is inbred? I wonder what the victims of police brutality would say when people realize that the said police brutality is part and parcel of a carefully crafted system that was designed long ago to keep black people in a subaltern state. It did not exist in a vacuum. This is how Cornel West articulated it in a recent interview:

The nation-state, its criminal justice system, its legal system could not generate protection of rights and liberties. And now our culture, of course, is so market-driven, everybody for sale, everything for sale, it can’t deliver the kind of real nourishment for soul, for meaning, for purpose. And so when you get this perfect storm of all of these multiple failures at these different levels of the American empire – and Martin King already told us about [everything]…. When I saw those pictures there in Atlanta, you could see Martin right there in Atlanta saying: I told you about militarism. I told you about poverty. I told you about materialism. I told you about racism and all of its forms, whatever forms it takes. I told you about xenophobia. [Today] … these chickens are coming home to roost. You’re reaping what you sow…. And I thank God that we have people in the streets. Now you’ve got a younger generation of all of these different colors, and genders, and sexual orientation saying, “We won’t take it any longer.” But you know what’s sad about it, though, brother, at the deepest level? It looks as if the system cannot reform itself. We’ve tried Black faces in high places.

I know it is madness to keep pointing to the carnage we are witnessing today in America and indeed the world. It is mainly due to the sheer lunacy of a man, a coward to boot, who, instead of helping dissolve racial barriers, engages in denial, ignorance, and above all, trivialization of a system that has entrapped so many people for a long time. Are we surprised by his crude conduct? Of course not. After all, on June 20, 2020, a certain Donald Trump held a rally in Tulsa (Oklahoma) where, in 1921, up to 300 black people were killed like rabbits in one of the most horrific acts of racist violence. That the city is still haunted by the memory of a white supremacist massacre did not concern him in the least. What mattered to him and his army of white trash is the rally, which was thwarted by the lack of participation, even if he refused to accept moral responsibility should they become infected with the virus. After all, the victim loves its executioner. We do not expect less from a soulless, hyena-like man who runs for shelter in a bunker when the going gets rough and then comes out, surrounded by straw dogs, for a photo-op, holding the holy book in front of a church as if he were the author posing for a publicity stunt.

A poseur to boot, Trump is deliberately bent on ignoring the reality on the ground; a reality that is witnessing how active mobilization has become the raison d’être for so many people fighting tooth and nail to change the status quo. We see it happening in Seattle where

Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone or CHAZ (which its Black Lives Matter organizers on Saturday renamed the Capitol Hill Organized Protest, CHOP): four-plus blocks of street and sidewalk in Seattle’s traditional gay and bohemian nightlife district, surrounding a boarded-up police precinct headquarters that the mayor ordered vacated last Monday to dampen a week-and-a-half of escalating confrontations between police and protesters [stand tall]. From there, the fluid protests, spearheaded by BLM but involving a wide spectrum of activists and ordinary citizens, coalesced with surprising rapidity into something like a provisional government.

On June 9, 2020, led by Speaker Nancy Pelosi, the Democrats took a knee for nearly nine minutes in front of the House of Representatives in support of the Black Lives Matter Movement. A telling sign, the stand consolidated the daring step that Colin Kaepernick had effected some time ago. It is his signature that has breathed new life into the movement that is keeping Trump and his lynch mob on edge. The show of solidarity by the Speaker and Co. is an immense victory for all of us. They have given us the energy we need to maintain the pressure until November 4 when we are able to vote Rambo out of office. To do so, we must cross many rivers, and cross them we shall. In the meantime, we bear out the end of racial exceptionalism. The battle is fought before our very eyes by young people who are black and brown and yellow and white. They are determined to force a change in the way we see, think, and act.

We are all more or less of one mind. Most of us agree that if racist people believe that race is multiple (white, brown, black), the majority of us tend to think about race in the singular. We do it genuinely to denounce the system that has kept many of us on the margin for a long time. It came to be known as “racialization.” The wonder of it all is that in 2018 the French Parliament voted to rid the French Constitution of the word “race” except in one case where it appears, we are told, to deal with racism head on. Fair enough, but the inscription “without distinction of race” is misleading insofar as in France, the justice system is disposed to think theoretically about the concept of race instead of considering the acts of racism black and brown people are subjected to every day. It is all a pretense. Or, to put it another way, the problem is not to convince us into believing that the police are not racist, because they definitely are—according to Human Rights Watch, young black youths (Arabs in France) are likely to be stopped by the police for no apparent reason—but to question their motive. In order to understand racism, like sexism, one has to look at it from the point of view of those who are subjected to its insults, torture, and pain; in fine, its victims. When the singer Camélia Jordana musters the courage to scream the world down, she means it. The fear of the “men and women who go to work every morning in La Banlieue (suburb),” she sings, “and who are massacred for no reason other than the color of their skin,” must give us pause. Her attitude against inequality stands at the opposite end of the key board from that of the then French Minister of the Interior, Christophe Castaner, who had nothing to say about the matter except to denounce her in a diatribe: “The freedom of public debate does not permit (us) to say everything and anything.” Why not? One may ask. Castaner ignores the calls for new ways of looking at systemic racism which is neither a social logic nor a faux pas, but rather an institutional practice (of society), the effects of which are measured by the great pain they wreak on black and brown people. On the other hand, the US Attorney General, William Barr, another hollow man, whose reason for being is to lie to the world and cover up his misdeeds while fattening himself, declares in an interview with the CBS program “Face the Nation”: “I don’t think that the law enforcement system is systemically racist. I think we have to recognize that for most of our history, our institutions were explicitly racist.” A dipping donkey, Barr would never go so far as to be the Attorney General for all Americans, including black people, instead of acting as the right-hand man for Trump and Co. Instead, he fantasizes about what he calls “justice for all.” All the more so since systemic racism remains implicit in all the institutions across the scale. A case in point is the subtle and overt racism experienced by black athletes on the job. Chris Grier of Florida is the NFL’s only black general manager to hold the post out of 32 white NFL teams across the country—a post nearly always out of reach of black people. If this is not deep-seated prejudice, what is? And get this dizzying fact: 88% of police stops in 2018 involved black people, while only 10% affected white people.

Of course, we are not done with racism nor with sexism for that matter. The end of racial and/or sexual exceptionalism simply means neither the one nor the other depends to a large degree on the will of the people on both sides of the racial and/or gender divide. West knows that our future is at stake. He put it succinctly:

Too often, our Black politicians, professional-class, middle-class, become too accommodated to the capitalist economy, too accommodated to the militarized nation-state, too accommodated to the market-driven culture, tied with celebrity status, power, fame, all of that superficial stuff that means so much to so many fellow citizens. [We] … got a neo-fascist gangster in the White House who really doesn’t care, for the most part. You got a neo-liberal wing of the Democratic Party that is now in the driver’s seat with the collapse of Brother Bernie. And they don’t really know what to do ‘cause all they want is show more Black faces, but oftentimes these Black faces are losing legitimacy, too. Because the Black Lives Matter Movement emerged under a Black president, Black attorney general, and Black Homeland Security, and they couldn’t deliver. You see? So that when you talk about the masses of Black people, the precious poor and working-class Black people, poor and working-class brown, red, yellow, whatever color, they’re the ones who are left out, and they feel so thoroughly powerless, helpless, and hopeless – then you get rebellion. And we’ve reached a point now, it’s a choice between non-violent revolution – and by revolution, what I mean is the democratic sharing of power, resources, wealth, and respect.

He concludes:

If we don’t get that kind of sharing, you’re going to get more violent explosions. Now the sad thing is in this neo-fascist moment in the White House, you got some neo-fascist brothers and sisters out there who are already armed. They show up there at the U.S. Capitol and they don’t get arrested. They don’t get put down. Even the president praises them. You see what I mean?

Really, what West wants to tells us is that the miracle we all hanker for is a choice, a societal one. Can we honestly continue to reclaim racial and/or sexual exceptionalism, he seems to be saying, in the name of a white culture that is determined to carry on excluding a good section of the population because it is black or brown? The question has no easy answer. However, what is certain is that today, it is up to us and to the many young, happy white people who are on the right side of history to realize once and for all that universalism does not suffer from exceptionalism. After all, the very idea that we call “America” has failed miserably those who have built it with their sweat and tears and blood. The time has come to demand that this black and/or brown constituency get an honorable seat at the table as well as receive due credit for all the pain it has suffered for the last 400 years.

In and out of our hearts flows a jolt like no other we have felt in the past. It is exhilarating. We stagger as we take stock of the situation. The surge of pride at the sight of what we see and hear must give us pause as we continue to fight for the removal not only of the triangle, a Nazi-like symbol, once used by Nazis to degrade prisoners in concentrations camps, Trump and Co. put forward on June 18, 2020 but also for the dislodgement of two more statues—notably, one of Cecil Rhodes at Oxford University and another of Jean-Baptiste Colbert in front of the National Assembly in Paris. We have to follow in the footsteps of labor-controlled councils in municipalities across Britain, which fair-minded people lit purple in solidarity of BLM. The Royal Bank of Scotland and the Central Bank of England have apologized for having had close ties with slavery. They even promised a reparation of sorts to the victims. The decision came after the toppling of the statue of the slave owner Edward Colston in Bristol in June 2020. In France, the air has been heavy with smoke and teargas as young and not so young people took a knee and raised a fist in support of the carnage black and/or brown people go through every day. In Ghent, a statue of Leopold II, the Belgian king who despoiled and plundered the Congo as well as profited from cruelty and persecution while hundreds of thousands of Africans died in the process, was cloaked in a hood with the banner “I Can’t Breathe” and bespattered with red paint. In Copenhagen, the rioters chanted in unison “no justice, no peace.” There were skirmishes and tussles in Sweden; US embassies and consulates from Milan (where there was a flash mob) to Krakow (where they lit candles) were the focus of protest, while tens of thousands of marchers, from London’s Trafalgar Square to The Hague, from Dublin to Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, violated social-distancing orders to make their voices heard. In Belgium, King Philippe has apologized for the first time ever for the “deep wounds” his country inflicted on Congo during the colonial period. However, the question of reparation remains unanswered. It is not enough to say that he is going to “combat all kinds of racism” and that he will “push for the reflection pioneered by the Parliament in order to finally pacify our memory” i.e. “to acknowledge the suffering of Otherhood.” The king falls short in facing the denial of the crime Léopold II committed during the colonial period when millions of Congolese people perished in the jungle while working in the mining industry of rubber and/or collecting ivory. We are more than ever ready at the rendez-vous, face to face with the past as well as beyond gestures of good will. There must be funds on tap to bring all the wrongs to closure. Failing that, the king is engaging in fantasy.

At this crucial moment, in this state of emergency, what is really at stake here? Everything we have fought for centers around the idea of racial and/or gender equality and justice. I mean the thing itself, what linguists call the “signifier” and “signified,” which make the sign that carries the meaning, not the hollow word. The recent decision 7/2 in favor, and the one before that 6/3 also in favor, by the Supreme Court are steps in the right direction. These decisions are landmarks for equality before the law. In the former, the court told us that no one is above the law and that includes Mr. President. In the latter, it ruled that federal anti-bias law covers millions of gay, lesbian and transgender workers. Another ruling against police brutality will be a giant step. In the meantime, we must interrogate the past, the present, and indeed the future. We need to engage in a war on bigotry and prejudice. One will have to be insane not to rise against the injustices; injustices inflamed by a venal, vapid, lowlife creature; an ineffectual and puffed-up, obvious idiot named Donald Trump, who continues his assault even on language in that he tells it like it is not. As a case history, it is the various ethnic groups’ demands for recognition that are perfectly legitimate and if the current demonstrations are clearly on the side of universal values, we have to make sure that they do not open onto a logic of rupture or withdrawal (into oneself), a radicalization or even a breaking down of energy. There is a potent common denominator in the revolts that were given rise to in the US and the rest of the world by the murder in cold blood of George Floyd and, in France, by the remembrance of the 1916-killing, still the object of a judicial inquiry that has been dragging for too long, of Adama Traoé: they have so far been inscribed in a history; one of struggles for justice, equality, and human rights; struggles that advocate non-violence and peace. Thus, in the US, the 1950s Civil Rights Movement and up until the mid-sixties, in South Africa, the long quest for parity led by Nelson Mandela or in France steered by the 1983-March for Equality and against Racism, have, in their own ways and in different contexts from one another, brought to the fore the universal values I am reflecting on here. They have done it with style and chutzpah and for that reason alone, we must point to the method they adopted to lead the fight; a method that has ruled out, at least for now, the risk to drift toward anarchy or even disintegration. It is in this sense that we ought to understand the callings on everybody to join forces and fight back with every fiber. So far, the stirrings are enthusiastic and powerful; indeed, they have not only reached large segments of the population but have also affected major public opinions. They have also affected those who, like Trump and Co., are obsessed by their lived experience of hatred, discrimination, prejudice, and violence. Such ado involves, democratically, the whole citizenry, without distinction of national origin or color of the skin. But prior to the time when they proved to be capable of becoming the main concern of all of us, and even, in certain cases, of obtaining a planetary echo, as it is the case today with the senseless killing of yet more black men and women or further down the line, when the results of the action are insufficient or untimely, it may happen that they fall into a logic of reversal, in which case they then take on other forms of struggle and/or other meanings in the bearing of arms against injustice.

In the same way, two cardinal measures can be implemented as soon as possible if we want to calm the situation. The first one centers around the demand for respect of universal values like equality, liberty, and the right to life, which has not yet managed to stand on its feet nor has it given way to hatred, anger, rage, or riotous violence. In due course, such logic can lead up to the moment when well-thought action will be able to exact non-violence. That is why scenes of rioting and looting, which marked the beginning of the uprising in the US following the death of George Floyd, ended paving the way for peaceful demonstrations and dignified ceremonies that were organized for his burial. Even so, nothing else can be done when mobilization slows down; when, in the eyes of the principal actors, the bitter acknowledgement of failure asserts itself, or insufficient political measures are late to arrive. Only then does the specter (of death) suddenly crop up all over the place where violence can erupt again at any given time. This latter one usually comes to remind us of the despair of those who are no longer able to find the stable in another modality of intervention. No wonder, then, that it was in the spin-offs of the Civil Rights Movement, and just before the 1965-Watts riots (a district in Los Angeles), that Bobby Seale and Huey Newton set up the Black Panthers Movement in 1966, which invited an action combining stellar exemplarity and concrete support for black communities across the nation, culminating in organizing in their midst screening tests of sickle-cell anemia. Later, its members, disillusioned and despaired, converted to radicalism while resorting to the armed struggle à la early Mandela. The second course of action that can suddenly arise prior to but mostly further down the line of an anti-racist massive rally has to do with the move from identity drifting to self- racialization. When the movement is not yet fully-fledged, the energies that will eventually put it in motion, are intensive, and above all, when the results are not up to the level the resistance movement aspires to, racism, instead of provoking a universal awakening, tends to run into a logic of rupture, a withdrawal, an identity crisis, and indeed, a closing (of the mind) that is racial in nature. This is the case when nearly a year after the 1983-March for Equality and against Racism in France, a second march in 1984 ushered in the crumbling of the movement, which led to a progressive dis-involvement with its worldliness. Above all, that is how for several years appeared, again in France, shifts of the population calling for both a cultural and postcolonial set of themes centering around the revival of heritages, traditions, customs, and values that are exclusive to the different groups of victims of a pernicious system, itself deep-rooted in the colonial experience, and more or less blown to bits by it.

The question surrounding issues of identity claims is also a legitimate one, even if sometimes it can turn into a radicalization of sorts, the main thrust of which swerves around an affirmation of identity. Here, one must give fitful thought to the current stirrings still that are taking place across the world. That they are peaceful in nature is not an accident. That they are well-nigh is more than a little relief at passing the test of hatred. We are thrilled at the thought that what has happened in a little month measures up to what happened in half a century or more. Still, we must not let up now. Indifference is not an option for us any more than slackening off. For now, we must adhere to an agenda that excludes all sorts of clashes between the races. A step in the right direction was taken by the European Parliament on June 19 when it adopted a resolution declaring “slavery a crime against humanity” and demanded that December 2 be declared a day of the abolition of the slave trade. The text, symbolic in nature, was adopted as follows: 493 for, 104 against, and 67 abstentions. Among those who voted against the resolution are 22 French members who subscribe to Le Rassemblement National, a right wing party led by none other than the debauched Marine Le Pen. Our success will depend to a large degree on the reaction of those institutions like the European Parliament, who have decided to right the wrongs of the past as well as on the direction public debate will take in the days to come. One thing is certain, though. It is not Trump nor the Senate, led by Mitch McConnell, a fascist with an attitude that will ease the pain of injustice in America. For when the president pretends that he is more than an adversary of the Black Lives Matter Movement, and that he is responsible for national unity, he deliberately fuels racial cleavages between communities while celebrating the ugly side of the clashes between “them” and “us” as he recently did in Mount Rushmore. His interventions have done nothing more than sow confusion in people’s minds and hatred in their hearts. On the other hand, in France, the then Minister of the Interior, Christophe Castaner, who at the beginning of the riots saw fit to create a rift between people with his declarations on the subject of the demonstrations that took place on June 2, which were linked to the death of Adama Traoré, spoke of the “outbursts caused by these gatherings, which are not legitimate because they endanger the health of all of us.” But soon afterwards, the French authorities, unlike their counterparts in the US, presented themselves as particularly aware of the brutality of the police toward people of Arab and/or black origins. In doing so, the government tried to appeal to the values of La République, which, in France, stands for the mode of expression of universalism. However, what the government forgot to note is that for now there can no longer be any prevarication. Everything must be faced, even if that means the likelihood of total disaster. The tone changed when the advent of this young new voice stood up to meet the challenge while remembering George Floyd whose untimely savage killing brought about all the changes we are bearing out today. Suddenly, this millennial voice not only informs us that the fight against racism is a commitment of the highest order but demands respect for the individuals, regardless of their color. It also recognizes their difference.

Like a virus, racism mutates, and every mutation makes it more dangerous. The old stereotypes decreeing the physical and moral inferiority of the targeted minorities make room for pseudo-cultural arguments destined to establish an incompatibility between the values and morals of certain “races” within a given society—say France. It is these narratives that enable clichés to prosper and also fester like resentments. It is not an accident that 45% of French people are convinced that “Islam is a threat to French identity” and that 34% of them believe that “Jews have run a financial worldwide conspiracy.” Moreover, the reader will regret to learn that it is in the work place that the question of “origin”—in a wide sense—raises its ugly head: nationality, birthplace, area code of one’s residence, name, physical appearance, attire, diction, manners, patronymic; the list is too long to call up. Origin remains the main source of discrimination. The phenomenon affects the public and private spheres equally. The odd thing about it is that all the great struggles for equality have been fought by white and black people together. They did it in the name of universal values. (We still remember how Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau and François Mackandal, a voodoo priest, achieved some success in organizing plantation slaves who led a rebellion against France in Saint-Dominique). As Cheikh Tidian Gadio, the Senegalese diplomat, put it: “I do not apologize for my blackness and I do not turn my back on white people.” Correct, in that to see everything in brown, black or white is to miss out on the beauty of the world. We do not claim a color, we ask for justice. “The tiger does not proclaim its tigritude. It pounces,” Wole Soyinka accurately prompts us. Justice, which is not a revenge match, must therefore punish racism in opinion and in action. It is in this sense that corrections are being made across the West. We are glad to learn that Uncle Ben’s rice farm scrapped the brand image of black farmer, and Quaker Oats is retiring the more than 130-year-old Aunt Jemima brand and logo, acknowledging how its origins are based on a racial stereotype. I hope they are genuine in their quest and that they are not just pretending to do the right thing in order to amass more profit. The pub chain and brewer Greene King and the Insurance Market Lloyd’s of London will make the reparations to the siblings of enslaved Africans in order to correct the wrongs they suffered during slavery. That the British Government of the time—when Slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833—should pay the compensation NOT to the slaves, but to the shareholders such as Simon Fraser, a founder subscriber of Lloyd’s, tells us a great deal about the way black people were treated then. We are also glad to learn about a petition, signed by 1,000 insiders, accusing Médecins sans Frontières, the in vitro fertilization baby laid by none other than Bernard Kushner in 1971, the once upon a time darling of the Left turned neo-conservative in the Sarkozy government. He is the one who masterminded the invasion of Libya and killing of Muammar Khaddafi. The truth, which had been covered up for a while, emerged after the death the Libyan dictator. The petition maintains that the so-called humanitarian organization has shored up colonialism and white supremacy in its work done mostly by a privileged white team whose motive in life has run on a dehumanizing program that is racist in nature. These points cannot be too strongly emphasized. With this end in view, one may claim that the silver lining lies in the recent decision by the US Supreme Court which blocked Trump from cancelling the DACA immigration program; the Obama-era platform that offered undocumented immigrants brought to America as children the chance to legally reside in the country. The vote was 5/4 in favor. Hail to Chief Justice John Roberts who tipped the balance in favor of the program. Choke on it, Mr. President!

We are also glad that the saga called Gone with the Wind is dead and off the shelf, at least for now. The decision to do away with it came when HBO Max decided to take it off the list of classics after John Ridley, the producer of 12 Years a Slave complained about its misrepresentation of black people during the Civil War (1861-1865). The novel and indeed the movie are pretty deceitful because they show the desire to celebrate white heritage in its full glory. America is the only country in the world that glorifies the enemy. If not, how can you praise a traitor which the Confederacy was when the South faced the North in a bloody war that claimed the lives of more than 800,000 people? Its member states fought tooth and nail against the US army. The script by Victor Fleming (1889-1949) was drawn from the novel, with the same title, written by none other than the white supremacist, Margaret Mitchell (1900-1949). The film was screened in 1939 to a fanfare of publicity. The financial gain the novel and the movie made is to this day a landmark in both the literature and film industries. And if the former sold 30 million copies, the latter won a record of eight Oscars—the most lucrative deal in the history of Hollywood. Until recently, the one and the other became totems as the French anthropologist, Claude Levi-Strauss, understood the term, to the extent that the fans, mostly white, gave them the acronym “GWTW.” In addition, ever since its publication, Gone with the Wind has been a living symbol of the rallying cry of the Ku Klux Klan troops as well as of all those who look back nostalgically to the good old days in the good Old South with its mansions, southern belles, plantations, and why not, slaves. Originally, the novel sprung from a desire to foil anti-Tom literature in reference to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe, one hell of a reference for abolitionists. To thwart Beecher, Mitchell espoused without nuance the ideology of the Lost Cause—that is to say, the description of slavery as a happy institution, a southern belle family welded by affection and not by servitude, a lost paradise devoid of cruelty but also a tendentious representation of the war and the years that followed the reconstruction of the defeated Confederate South. The story is depressing, inhuman, and perverse, to say the least.

One of the most telling responses to the Black Lives Matter Movement came out in the shape of a PSA (Public Service Announcement) that gave prominence to Hollywood iconic figures who thought it wise to be part of an obscure agenda against hate. The slogan “I Take Responsibility” was launched to showcase the stand of Sarah Paulson, Julianne Moore, Justin Thoroux, among others, who saw fit to censure their own erstwhile silence on police violence toward black people. However, the buck did not stop in Hollywood. For it has, of late, become the fashion to join the fray. Not only Hollywood moguls but also rapacious CEOs, mega-corporations, and hallowed institutions lost no time to jump on the wagon and claim that they are on the side of black people. The move is false because it lacks genuine commitment to reform. In point of fact, what the Black Lives Matter Movement has taught us is that we must revisit our ways of seeing and/or telling. It has also shown us how complicit we have been in allowing an ugly thing (i.e. racism) to happen and indeed foster for such a long time. Still, we are somehow unable to break the shackles of something we call “privilege,” even if those who find themselves on the right side of the color line keep telling us that we must “check” it. They, however, fail to remind us how “privilege-checking” may distract us from reflecting on the essential failings the movement has excavated and which may lead us to deal only with the simpler, personal solutions to racism. What the Hollywood PSA revealed is that the language of “white privilege” dilutes systemic inequality to a large degree and as a result, the purpose of the game of checking one’s privilege becomes a futile “public exercise in self-flagellation,” Momtaza Mehri gracefully writes,” focusing on the repentantly privileged while neatly obscuring how intrinsic anti-black racism is to the world. Why seriously challenge unequal resource distribution when all you need to do is renounce the privilege that gives you access to the very resources hoarded at the expense of others?” She asks and answers with equal aplomb:

To the privilege-renouncer, there is little need to address an inconvenient fact: the immense economic order that spans the globe has historically needed a black underclass, both domestically and overseas, to survive. Racial capitalism, a term popularized by the scholar Cedric Robinson (with its roots in apartheid-era South Africa), is a way of understanding capitalism’s processes of exploiting who it racializes and racializing who it exploits. We see this through the dispossession of indigenous people from their land, the transatlantic slave trade, and colonial enterprise.

Mehri is on target in arguing the case. What I would add goes in tandem with what she says. Alas, twinned with capitalism, anti-black racism lives on, and even flourishes, in what Jacques Derrida dubbed “la mondialisation,” which in his view, is an “alliance between a strange Christianity, similar to the death of God, and teletechnoscientific capitalism.” It is the latter one that has kept Africa, for example, in bondage to the West, and now China, through the extraction of all of its resources by vulturine and greedy lending organisms like the European Central Bank, the IMF, Exim Bank of China, and the World Bank as well as by giant predacious corporations such as Amazon, Microsoft, Alibaba, Google, Shell, Facebook, and the like. The effects on the environment are devastating, to say the least. What is ironic is that the local bourgeoisie gets much benefit from such shady undertakings while poor people bleed to death. The privilege theory has also demonstrated how the Black Lives Matter Movement has spawned an elite of black commentators and celebrities who have been at the forefront of every debate, late night show, and morning show to sermonize young black people on how they should behave when faced with police brutality, forgetting how privileged they are and how privilege-less those who are standing up for equality remain. They also forget that dearth of privilege can be fatal. No one has articulated this latter point better than Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who defines racism not as enmity via-à-vis those without privilege, but rather a measure that begets a “group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” This is really and truly accurate when we weigh the confounding number of black people dying of SARS-CoV-19 at three times the rate of white people in America. In the United Kingdom, the death rate of black people is more than triple that of their white countrymen and women. A large number of people die because they are poor. They simply cannot afford health care. It is in this sense that many people have made the connection between the death of George Floyd and that of Miguel da Silva in Brazil, a little boy who fell from a high-rise building while the owner of the household where his mother labored from sun rise to sun set watched without a care in the world. The incident tells us in so many ways about the way black domestic workers are treated on a daily basis. Note how the poor take a hammering when they find themselves in the crossfire between race and class. It is called power.

It is a hard thing to describe what you really feel when an issue engages your emotions. Writing on it touches you like a lover, with a lover’s trepidations. That is why the official discourse on anti-racism has forced many of us to rethink our stand in the world. While we embrace the effort, we must continue to self-reflect. Getting rid of our prejudices ought to be accompanied by the deconstruction of the rationales, edifices, and finances that have fully sustained global anti-blackness for a long time. Or, to put it as Momtaza Mehri did is to be reminded of the luminosity of her argument toward race, privilege, and above all, class.

Being courageous enough to reimagine the world as we know it will only deepen our genuine solidarity with those who are currently struggling to survive. Instead of timidly admitting to our various privileges, let’s ask ourselves what a world where all black life matters everywhere would look like—and accept nothing else.

I would like to think that she is not alone in raising awareness to the gripping issue we all face today because her argument displays a wise benevolence, a dexterity to see both tragedy and the soft glow of redemption. The result is a rich, commodious narrative whose power is matched only by its generosity of vision.

It is with humility that I want to end this essay with a reference to a cappella song by the 12-year-old Keedron Bryant. The song, penned by his mother, Johnetta Bryant, is a hymn to freedom. It also addresses the weight of social injustice in America and indeed the fear of a youth to face adult life in a country where he can be killed simply because he is black. Listening to Keedron singing his song, one can only surmise that it casts a chill over those of us who care about the plight of an entire community trying to hammer some sense into its life. That Keedron should release his song at a time such as the one we are traversing is pretty prophetic. At this point, I have an outré avowal to put forward. In addition to the joy one feels listening to “I Just Wanna Live,” one cannot help but deeply reflect on how it rings the chimes of the commemoration of the ending of slavery in the US on June 9, 1865, nearly two years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. The video of the performance that was made by Warner Records is even more telling; it features brown-and-black-and-white stills of protestors holding signs of the poignant lyrics, which I must quote:

I just wanna live

God protect me

I’m a young black man

Doing all that I can (Can)

To stand

Oh, but when I look around

And I see what’s being done

To my kind (Kind)

Every day (Day)

I’m being hunted as prey

My people don’t want no trouble

We’ve had enough struggle

I just wanna live

God protect me

(Just stay right by my side)

So many thoughts in my head (Head)

Will I live or will I end up dead? (Dead, dead)

It’s an unequal sequel

No matter where I be

There’s no place safe for me (me, me, me)

Oh, oh, oh-oh

I’m not asking for too much

So Laord please, help

I just wanna live

God protect me

The devil knows who else from all the ends of America and indeed the rest of the world where these handsome black and white and brown young and not so young people scream with anger, crimson like fire, while their (and our) hearts shout for joy at the midnight hour when Trump is no more. Hallelujah!

Mustapha Marrouchi is a writer on a wide range of topics including literature, politics, cultural criticism, and Islamic issues. He is the author of half a dozen books, including Edward Said at the Limits.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER