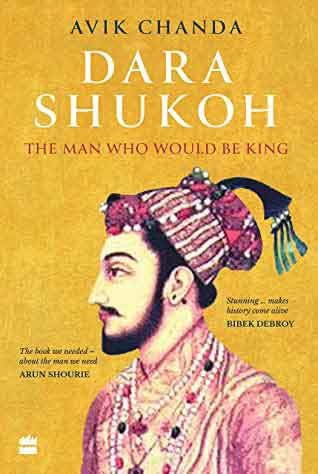

Title: Dara Shukoh: The Man who would be King

Author: Avik Chanda

Publisher: Harper Collins, 2019

Scanning the list of books already written on Dara Shukoh, I wondered why the author had chosen to write yet another book about Dara Shukoh, but that was before I came across Avik Chanda’s impressive work. A magnificent tome, it is richly palimpsestic and multi-layered and articulates the many complex layers of its protagonist’s personality and the forces that he had to grapple with. The book also displays an impressive array of materials and archives that were sourced by the author in putting together this fascinating chronicle.

In adding to a genre of what is known as popular history, the author has left no stone unturned. In doing so, he neither puts Dara on a pedestal, nor does he vilify him. Instead, he shows his protagonist’s limitations in his military campaigns, his aloofness and withdrawal from much of court politics, his intellectual leanings and his impatience with the petty nitty gritty of everyday politics on the ground, which often came across as arrogance to the people surrounding him.

Avik Chanda’s prodigious research helps him write what seems like the definitive version on the tragic prince.. About Dara Shukoh, he writes:

The emperor’s Shah Jahan’s favourite son, heir-apparent to the Mughal throne prior to his defeat by Aurangzeb, Dara has sometimes been portrayed as an effete prince, utterly incompetent in all military and administrative matters. But his tolerance towards other faiths, the legacy of his philosophy and the myriad myths surrounding him, have far outlived him and continue to fuel the popular imagination. In truth, the Crown Prince was a highly complex person: a visionary thinker, a talented poet and prolific writer, a scholar and theologian of unusual merit, a calligraphist and connoisseur of the fine arts, and a dutiful son and warm –hearted family man.

He also goes on to add:

…he was also cold and arrogant to the mass of courtiers and commanders, whom he felt were inferior to him, intensely superstitious by nature, easily swayed by mystery and magic, an indifferent army general and shockingly naïve in his judgement of character.

Chanda thus sets the record straight; there are no heroes and villains in his version. Instead, we are presented with a complex, multi-faceted scholarly man whose aesthetic taste and judgement were impeccable and one who could participate in scholarly debate and disputation with the best scholars of his time. A man of eclectic tastes, entrenched in his faith, deeply spiritual and almost other-worldly, Dara Shukoh did not like the strict asceticism of the mendicants. Instead, he believed in a faith full of love and compassion, and experienced nothing but supreme disdain at the Machiavellian machinations of the nobles and courtiers surrounding the king. Interested in mysticism, he was also open in his pursuit of religious knowledge, heterodox rather than orthodox.

Biographies can be of many types, hagiographical, celebratory, laudatory and critical. The best biographies are the ones which show not only fidelity to fact, but also stop short of creating two-dimensional cardboard cut-outs of its protagonists as heroes. Instead, the author undertakes a prodigious amount of research and steers clear of the epistemic trap of producing historical stereotypes. Rather than depicting heroes and villains, who are judged based on present standards of morality, we have historically dense, nuanced characters whose impulses and motives are subjected to psychological scrutiny. Thus Dara writes of his encounter with Mullah Shah, an experience so profoundly moving that he felt it had to be recorded:

The doors of divine bounty and mercy were opened upon my heart and he(Mullah Shah) gave me whatever I asked. Now even though I belong to the people of the world…..I am not one of them, for I have known their ignorance and affliction. Even though I am far from a dervish, spiritually I belong with them.

Dara Shukoh goes on to add:

In the discipline of the school to which I belong, there is contrary to the practices laid down in other schools, no pain or difficulty. There is no asceticism in it, everything is easy, gracious and a free gift. Everything here is love and affection, pleasure and ease.

Dara is an avid notetaker, and wonders, whether like his grandfather, Jahangir, he too, should keep a detailed journal. We remember also the richly woven narrative and sensuous details of the Baburnama (written originally in Persian by Abdul Rahim, 1589-90, and translated later from the nineteenth century onwards), which has come in for a fair amount of appreciation and critical work.

It is in these moments that we see the panoramic sweep of monumentalist history and historiography interspersed with jewels like these, little vignettes which record the still, small voice of history. This massing of small but telling details, like Dara’s relationship with his wife, and his sister, Jahanara Begum, shows a man to whom humanity is of paramount value, a man who seemed to have an understanding of the bedrock of our common humanity. While Dara’s understanding of the nuances of his faith, especially Sufism, is truly remarkable, with its notions of tawhid and dhikr/zikr, fana (love and devotion), ideas that are similar to many ideas within the contours of Bhakti devotion. We are in danger of losing sight of this substratum of a common devotional and cultural imagination in the present climate of intolerance that seems to sweep across the world.

Even as he extols Dara Shukoh’s understandings of these nuances, Avik Chanda also mentions, in almost the same breath, that his immersion in the biography of Sufi saints, Nafahat-al-Uns, results in his neglect of state affairs and administration of the empire. His ignoring the call of duty is overlooked by his doting father but noticed by the courtiers.

Historical agency and history’s inevitability are both in evidence here. Further, it is noteworthy to see the intelligence and capabilities of Dara’s sister, Jahanara Begum. Apart from remarkable women like Mehr-Un-Nisa or Nur Jahan, there were many notable women in the Mughal court. It is interesting to speculate if there could be a ‘her story’ (or her stories) that we could wrest from the margins of this historical and biographical discourses. There are more stories here, not only the tragedy of Dara but of his handsome, noble , dignified son, Suleman Shukoh, which leaves a lasting impression on Zebunissa, Auranzib/ Alam’s daughter who had been betrothed to her cousin and then turns rebellious, penning verses that reek of apostasy, as if to avenge his execution. Aurangzeb may have won the throne, but that victory certainly comes at a cost.

The book ends on a note where there are no absolute winners or losers. As Aurangzib/Alamgir realises, with hardly and inheritors who are both competent and trustworthy, his earthly achievements fade before Dara Shukoh’s reputation, which seems to grow in posterity/ posthumously. In a sense, all historical events are but wrinkles in time, as viewed from the perspective of eternity.

Reading through Avik Chanda’s account, it is worthwhile to pause for a moment and think about the purpose and function of history, both in narrativising as well as studying it. History is not just a compendium of facts about the past, but a revisiting of the past in the light of the present. Further, there is no one overarching historical truth, but a series of facts which are woven into narratives with different and varying interpretative twists, from varying ideological perspectives and vantage points.

To that extent, the history and biography of a man who stood for a confluence of Indo-Islamic tradition and culture, went beyond its doctrinaire aspect, and embraced mystical traditions which embodied the richest motifs of Sufism, so remarkably similar to that of the Bhakti movement calls for varied interpretations. It is interesting — and at times tempting — to speculate, in a counterfactual way, whether history would have been any different if Dara Shukoh, and not his brother, Aurangzeb, had ascended the Mughal throne. Perhaps not, since history is the great leveller, devouring good and bad alike as it races and hurtles through time and space.

Dr Meenakshi Malhotra is Associate Professor in English at Hansraj College, University of Delhi. She has edited two books on Women and Lifewriting, Representing the Self and Claiming the I, in addition to numerous published articles on gender and/in literature and feminist theory. Some of her recent publications include articles on lifewriting as an archive for GWSS, Women and Gender Studies in India: Crossings (Routledge,2019),on ‘’The Engendering of Hurt’’ in The State of Hurt, (Sage,2016) ,on Kali in Unveiling Desire,(Rutgers University Press,2018) and ‘Ecofeminism and its Discontents’ (Primus,2018). She has been a part of the curriculum framing team for masters programme in Women and gender Studies at Indira Gandhi National Open University(IGNOU) and in Ambedkar University, Delhi and has also been an editorial consultant for ICSE textbooks (Grades1-8) with Pearson publishers. She has recently taught a course as a visiting fellow in Grinnell College, Iowa. She has bylines in Kitaab and Book review.

Originally published in Borderless Journal

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER