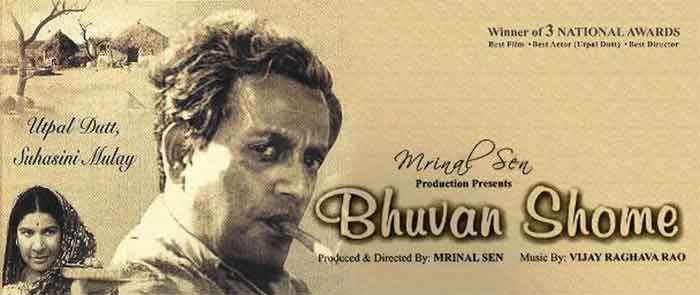

It is difficult not to miss the irony in the timing of Mrinal Sen’s passing on, roughly coinciding as it did with the fiftieth anniversary of perhaps his best-known film, BhuvanShome. It is generally agreed that it is with this film that the seminal movement called ‘New Indian Cinema’ began. The movement was an ideological/political body of work that questioned the popular commercial cinema which had preceded it for decades. The best specimens of the new cinema combined the creative and the meaningful with the interrogative and the critical. If the watchword of the earlier cinema was ‘entertainment’, cooked up very often in a shallow and sloppy sort of way, that for the new cinema was ‘enquiry’. Frequently, the questions, posed in an activist spirit, hovered round the overall uncertainty about where the Indian nation and society were headed for.

The movement came at a time of intense social and political turmoil. Gandhi was still loved and respected, but seemed to belong more to history than the breathing present; Nehru had been dead for five years, the party he had shepherded in power for almost two decades hardly resembled the one that had helped usher independence more than any other agency. Sen and several younger kinsmen portrayed much that was wrong with the system. They noticeably distanced themselves from the mundane cinema of studios, stars, high-pitched social dramas, and historical/patriotic/religious sagas that held audiences across the country in thrall. The brave new lot plunged into social and cultural interrogations around a wide range of subjects, including caste, class, feudalism, political degeneration, corruption of the urban elite, unemployment, poverty, gender bias, or the growing lumpenization of the lower and middle classes as a fall-out of lopsided economic development. Everything came to be closely observed, dissected and analysed.

If the content of the best examples of New Indian Cinema was bold and challenging, the same is to be said about their forms, styles, aesthetics, discourses and narrative modes. Everything was a sea-change from what had obtained previously. They critiqued the old with insight, courage and conscience till such time when, inevitably, they seemed to have exhausted themselves. True, they did not click all the time, but very often they did, drawing appreciation from small but loyal audiences at home and, more often, abroad.

In Bhuvan Shome, Mrinal Sen used a charming, earthy style to relate the ‘fall’ of a public official who, from the look of things, appears to think no end of himself. Perhaps, his reputation for professional correctness and adherence to principles has gone to his head. The film tells the story of an encounter, brief and tender, between the middle-aged man and a young village woman, enlivened by spurts of humour that few had thought Sen to be capable of till then. The coming together of the true-blue city bureaucrat and the young woman became an enjoyable metaphor for the traditional rural-urban divide.

The encounter has a ‘sobering’ effect on the visitor in more ways than one. Filmed in an idiom bordering on the idiosyncratic, Bhuvan Shome played a major role in creating for some years at least, a small but important audience across the country for a new kind of film art that smelt strongly of local elements, yet conveyed universal meanings. The soft breeze of culture-specific regionalism that blew across the film, lifted it to impressive heights of authenticity. The scenes of Utpal Dutt, in the role of the visiting official, trying to put on an elaborate Saurashtra pugree, is one of the many enduring memories of the film. So is the cameo of Sekhar Chatterjee as a bullock-cart driver giving Dutt a ride.

Eleven years after the making of Bhuvan Shome, the National Film Theatre in London organized a Mrinal Sen retrospective. A brochure brought out on the occasion said of the film, which had by then attained a near-iconic status both at home among aficianados of the ‘other’ cinema, as well as on the international festival circuit : “The first low-budget film financed by the government and a landmark in film history, it encouraged official sponsorship of the ‘art cinema’ which began the Indian ‘New Wave’. Set in Gujarat and made in Hindi (out of a story in Bengali), the film tells the story of an ‘honest’ bureaucrat whose colonial values are undermined by one of Sen’s most charming characters – an unsophisticated village girl.”

What the NFT brochure failed to notice was that the ‘unsophisticated village girl’ could well have been playing her own little ‘sophisticated’ game of trying to save her husband – a railway ticket-checker facing the threat of dismissal from service for committing an act of impropriety, whose papers are with Shome. True, she is not aware of Shome’s identity and knows him only as a big railway official come on a duck-shoot, but the feeling with which she asks him to plead with ‘Shome Sahib’ to pardon her husband, is enough to melt the aging man’s heart. The stern-to-view bureaucrat is ‘tamed’ or ‘humanized’ and the husband is let off with a warning, but the fact of the matter seems to be that Shome, for all his superior airs, has allowed himself to be ‘corrupted’ in the process.

A self-righteous widower who had parted ways with his son on account of an unspelt act of waywardness on the latter’s part, succumbs to the entreaties of the young woman, thereby joining in the riot of corruption in the public arena. (More than once, Sen had said that it was not his intention to portray a ‘tamed’ Bhuvan Shome, only to comment on the ways of the bureaucracy, but there are many who hold the view that here is a man with a chink in his armour and is not above committing a professional lapse or indiscretion, even if inadvertently.)

In an ending laden with irony, the shifty-eyed ticket-checker Jadhav Patel (played by Sadhu Meher) writes to his wife Gowri (portrayed by Suhasini Mulay) : “Shome Sahib has pardoned me. You’ll be pleased to know that I have been transferred to a bigger junction, which means increased earnings!” Clearly, without meaning to, Shome Sahib has become an accomplice to the malcontent Jadhav Patel’s unreformed ways and a passive contributor to the culture of corruption which was the principal bane of British India, continuing with Nehruvian India, and has continued with a vengeance ever since. (Here, it would perhaps make sense to mention that the Railways, in particular, was and is proverbially notorious for the corrupt ways of its officers and workmen alike. Both Bangla literature and cinema are full of references strengthening the popular impression about the menace of malfeasance synonymous with the country’s largest employer.)

Since Mrinal Sen’s films, arguably more than any other Indian director’s, lend themselves to meaningful political interpretations, one could perhaps justifiably take an initiative in enlarging the scope of one’s ‘reading’ of Bhuvan Shome’s change of heart and Jadhav Patel’s refusal to reform. The first Indian Prime Minister was to have found nothing wrong in reposing his confidence in the ’50s and ’60s on some, for instance, BakshiGhulam Mohammad in Kashmir, or SardarPartap Singh Kairon in Punjab, both of whom were given to settling accounts with political opponents using highhanded methods, apart from being suspected of committing financial irregularities. The Nehru era was tainted by the murky doings of people he counted among his foremost associates, such as V. K. Krishna Menon or T. T. Krishnamachari.

If the cause of public morality suffered in the case of Nehru turning a blind eye to the shadowy activities of some well-placed fellow-Congressmen, corruption in an infinitesimal but nonetheless equally sure way prevailed in the case of BhuvanShome exonerating the errant ticket-checker who, by his own admission, is emboldened to plan to become more ‘adventurous’ than before.

If, as Sen put it, “a film must project contemporary attitudes”, then it stands to reason that it must also be subjected to interpretations in keeping with contemporary political, social, cultural and historical situations. Failing to do so would amount to being disrespectful to the film in question, its maker, and its audience, or rather,the more discerning members of the audience. Like any original work of art seeking the remarkable in the seemingly ordinary, BhuvanShome has made its way into many hearts and minds in diverse ways. Over the years, viewers have come up with a variety of ‘readings’, each contributing in its own way to the legendary status of the film. No amount of undeserved carping by even such a one as Satyajit Ray, who thought it proper to dismiss the film in an acrimonious seven-word summing-up – ‘Big Bad Bureaucrat Reformed By Rustic Belle’ – has been able to cause any lasting damage to its reputation.

Seen today, fifty years after its making, BhuvanShome still engages the curious viewer’s interest by virtue of the simplicity of its story-telling; the frenetic pace at which it moves; its mesmerizing use of the tabla combined with varied incidental sounds, which together contribute to give the film its unique structure; the innovativeness of its editing; and the memorable performances of its lead and other players. The film’s excellence came to be underlined in a definitive way by its winning the most coveted national awards – for best film and best director. New Indian Cinema couldn’t possibly have begun on a more encouraging note.

Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER