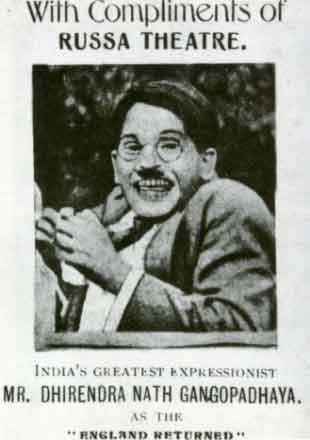

A hundred years ago, a silent film called Bilet Pherat (England-Returned) was made. That pioneering work placed its maker by the side of such greats of early Indian cinema as Dadasaheb Phalke and Hiralal Sen.

The example and exploits of Dhirendranath Gangopadhyay, or DG, as he was popularly known, were been recalled on many occasions by Mrinal Sen or Dinen Gupta, the well-known cinematographer, both of whom served their apprenticeship under the older director’s affectionate and watchful eyes.

DG(1893-1978) could have been anything he wished to be, such was his prodigious talent in more than one field. Added to this were his social connections and friends in the right places. Among his well-wishers was Rabindranath Tagore who gave his daughter, Mira Devi, in marriage to DG’s elder brother.

But DG’s temperament or his expectations from life were not cut out for easy success. The visionary in him, wanting to navigate virgin waters, made him give up a handsome job of Rs 1300 per month as Principal of Nizam’s Art College in Hyderabad. The year was 1918; and the salary blithely given up in favour of an uncertain career in filmmaking, represented nothing less than the loss of a small fortune.

Out of that decision to work in films in Calcutta grew a scathing critique of the manners and hybrid ideas of Westernized oriental gentlemen so uproariously portrayed in Bilet Pherat (1921). Besides being a pioneering work in a medium that was still groping to find its feet on Indian soil, Bilet Pherat stood for nationalist feelings in a period of great political upsurge.

An abhorrence for behaviour that was borrowed and barren was an important aspect of this film. In the decade between 1921 and 1931, DG directed more than a dozen films on a wide range of subjects, often using humour laced with sarcasm to expose human follies and foibles.

Some of the films indicate the director’s strong social conscience and his attitudes fashioned by socialist convictions. The Marriage Tonic (1923) or Takay Ki Na Hoy (Money Makes What Not, 1931) reveal DG as a commentator with a flair for the absurd and the bizarre.

DG made his first ‘talkie’, Mastuto Bhai, in 1934. This was followed in the same year by Excuse Me, Sir in Bengali and Night Bird in Urdu. Cartoon, made in 1949 in Bengali, was his last outing. Many of these films were box-office successes, and their popularity is to be measured in terms of the eagerness with which the educated of the day picked up DG’s dialogues or scene-stealing gestures as an actor.

It is to be remembered that DG was seen to advantage in the role of the lead performer in many of his films. His histrionic skill was evident in the varied roles he played. From the absurd elite to the hypocritical Brahmin priest, DG carried off each role with his customary panache.

Old-timers remember him to this day as much for the lines he wrote as for his acting, especially in humourous roles. But DG’s career as an artist, intellectual, producer and citizen was far from being a bed of roses. There were many thorns strewn on the way to success; and many enemies were made. Although an extremely pleasant and generous person, he was wise enough to understand that when one sets out to achieve something out of the ordinary he inevitably meets with impediments.

One serious obstacle that DG faced was the unrelenting opposition of the orthodox sections of Bengali society of the day. Cinema, or ‘bioscope’, as it used to be called in those days, was not highly thought of in so-called polite society.

What to speak of making a film or acting in it, many shrank even from the thought of frequenting the theatres, for even the filmgoer was widely looked upon as someone without character; and to get women to act in films was well-nigh impossible.

Once DG approached a friend of his and asked whether he would let his wife act in one of his films. The friend promptly replied, “Why don’t you get your wife to act in your film?” DG lost no time taking up his friend’s suggestion. This was how Romola Devi, DG’s wife, came to act in his films. The creative iconoclast that he was, DG’s life is studded with examples like this of courage and commitment in the face of social censure.

DG himself is on record on the subject of individual initiative to overcome popular prejudice. He wrote, “Let me talk about cinema in 1918 when everything was topsy-turvy; it looked like that when we came to the medium of cinema. None can imagine what a storm blew over our heads when we came in contact with the art of cinema. We were then looked down upon as ‘untouchables’ by orthodox society. It was a time when we had to work only with theatre professionals… After the release of my Bilet Pherat, it won huge applause and box-office collection; but, for that, we were lambasted by a section of the orthodox society. All the artists were panned heavily for nothing. It was a cruel experience.”

If patience and the urge to look beyond one’s immediate situation has any lasting reward, DG’s rich and eventful life is ample proof of it. Fortunately, it was given to him to see before he closed his eyes that filmmaking had received the respect and importance it deserved. The sea-change in popular perceptions about the world of film art, as indeed the worth of those who participated in the construction of a film, enthused the great man.

As much is evident from what he wrote, “(But) now cinema has become a part and parcel of daily life. No one now raises a questioning finger or doubt about the usefulness of cinema; and people feel happy if they can somehow be linked to it. When I left the Principalship of the Art College in Hyderabad and devoted myself to the art of cinema, I had never dreamt of spinning out money. It was my profound love for the medium, for which I could sacrifice anything…”

DG had the visionary’s proverbial gift of spotting a talent when he saw one. At least two names can be mentioned in this connection. Both the director Debaki Kumar Bose and the legendary actor-director Pramathes Barua worked under DG’s banner (the Indo-British Film Company) before going on to work with others or on their own and carve out a niche for themselves in the folklore of Indian cinema.

DG got together in one place other great but, alas, now-forgotten names like Dinesh Ranjan Das, Hem Gupta, his wife Romola Devi, Sukumar Dasgupta, Kanai Ghoshal, Sabita Devi, Satishchandra Ghose, the cameraman KG, and others.

DG was to write with pride and a deep sense of satisfaction about the quality of artistes and technicians he could muster and coordinate: “(A refurbished Indo-British Film Company) became an institution of people and ladies coming from noble families. No doubt, for such an act I had to suffer enough humiliation.”

What comes across from these words is the director’s quest for respectability and social acceptance not only for himself but also his team; and, more important, to earn for his chosen medium the status of seriousness and relevance that he was convinced it deserved.

In the evening of his colourful and chequered career as both creative artist and film entrepreneur who sought to accomplish channels of production, distribution and exhibition in Calcutta alongside those in non-Bengali hands, such as the powerful and prestigious Madans, DG was gratefully acknowledged as a genius who made filmmaking an honourable proposition for generations to follow.

The Padma Bhusan was conferred on him in 1972 when he was almost 80; and the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 1976 in recognition of a lifetime spent in the service of cinema. The maverick, who had defied scorn and opposition to do what he wanted to do, had indeed come a long way.

But the most lasting recognition of DG’s lifework is perhaps contained in the perceptive words of the great Bengali litterateur Tarashankar Bandopadhyay who, felicitating DG on his seventieth birthday in 1963, wrote: “The path that Satyajit Ray travelled to become famous truly began long ago; had you turned your attention to the genesis, you would discover a colossus standing high, and he is DG.”

Come to think of it, no award can exceed the value of one great artist’s praise for the work of another.

( Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.)

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER