With Chaitanya Tamhane’s second film, The Disciple, headed to the Venice International Film Festival in September, it may be worthwhile recalling, Court, his first film that bagged the National Award for Best Feature Film in 2015. As we live through the COVID moment witnessing the targetting of students, teachers, and poets, Court’s damning testimony of caste oppression and its tribute to people’s everyday struggle seems highly relevant today.

According to one estimate, over 81 cases of violence against Dalits were reported during the lockdown. In Court, Tamhane carefully unpacks the question of violence by revealing how Dalits occupy a highly tenuous position within the question of who is human. Argentine philosopher and semiotician, Mignolo, explores who the ‘human’ in human rights is, exhorting us to interrogate how our personal locations within caste embroil us in its violence, and how the discourse of human rights often negates the possibility of a radical politics, reaffirming instead the status quo serving the powerful.

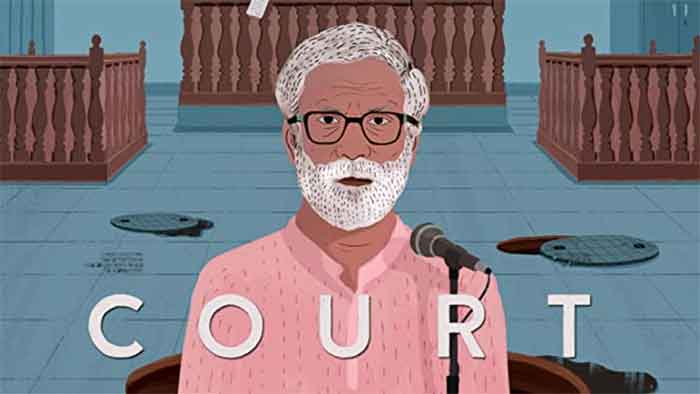

Court depicts the lives of those who are involved in a court trial after the death of a safai karamchari (sanitation worker), Vasudev Pawar, who dies of asphyxiation inside a manhole. Upon the death of Pawar, a Dalit activist, Narayan Kamble (played by Vira Sathidar), is arrested for abetting his ‘suicide’. Consequently, in the trial that follows, Kamble is linked to the death of Pawar through his revolutionary work as a musician and performer. While Kamble claims that he had no intention of aiding or abetting Pawar’s suicide, the police alleges, through a stock witness, that Kamble had performed a song urging safai karamcharis to enter into manholes and claim their own lives. In the hearing that follows, Kamble’s high profile lawyer, Vinay Vora (played by Vivek Gomber), and the state prosecutor, Nootan (played by Geetanjali Kulkarni), frequently clash on various issues, including the relevance of colonial laws within a post-colonial court, and the severity of Kamble’s sentencing.

Thus, Court provides an involved and telling commentary about law, justice, caste and revolution.

The construction of “human”, according to Mignolo, assumes that it is an all-inclusive “universal category that does justice to everyone”. Court shows how this supposed universality, further inscribed in the Indian constitution, proves to be exclusionary. In the due process of justice, we find Judge Sadavarte (played by Pradeep Joshi) and the Dalit widow of Vasudev Pawar, Sharmila (played by Usha Bane), enveloped by the problematic humanness of human rights, locked as they are in the antagonisms of caste, gender and class that mediate social relations within the court room.

The exploitation intrinsic to human rights

While Mignolo argues that the locus for the human in the global discourse of human rights is a white male, in Court, it is modelled around an upper caste male. Those who fall out of this category share a relationship that is colonial and extractive with those within it – that is, those who are human exploit those who are non-human. Vasudev Pawar’s relationship with the Brahminical Indian state is defined purely in terms of the surplus value his labour generates. He is not provided with safety equipment, and his death does not raise alarm as it would, if a human life were lost. Interestingly, prosecutor Nutan is also defined in terms of the work she does within the court room, and her unpaid emotional and physical labour within her home is not recognised.

A key question that arises in this regard relates to how the state operates to completely evade the standpoints and experiences of the Dalit. Mignolo argues that those protecting the power structures are the very same actors who speak on behalf of the human. Thus, Dalit issues are articulated by actors who seek to define the contours of humanness. This is evident in the case of Vinay Vora, whose arguments in the court room on behalf of Narayan Kamble, his client, are in English, a language that is entirely foreign to Kamble. Ironically, even as Vora appropriates the Dalit struggle to make his impassioned pleas, the court room is still preserved within the lingua franca of power, erasing the voice of Kamble, who as a Dalit is rendered non-human.

Violence and the Dalit Body

In the courtroom, Pawar’s death is sought to be framed as ‘asphyxiation due to the absence of safety equipment’. The extreme indignity meted out to Dalit bodies in treacherously perilous urban sanitation work is thus reduced to a question of ‘right to equipment’. Court thus reflects on how caste in urban India is erased, and the right to life and dignity is construed as a de-casted demand, simply unattainable for those who are non-human. The law is supremely inadequate in accounting for the daily violences that Dalits are subject to. This means that to be the subject of violence requires a quintessential humanness that some simply cannot aspire to. Vasudev Pawar is hence not a legitimate subject of state violence, and his death cannot amount to a caste atrocity unleashed by a Brahminical state apparatus.

Indian courts have routinely refused to use the word ‘atrocity’ in order to describe violences on Dalits that have ranged from the phenomenal to the everyday. The experience of law in and of itself is thus tantamount to extreme violence. Court’s incisive take on violence can also be understood through Agamben’s ‘state of exception’ – the fact that law contains within itself the language for its own suspension. Thus, the violence of law occurs as much, in its absence. Kamble’s revolutionary work is quelled by the the Dramatic Performances Act and UAPA, effectively suspending any claim he can have to the constitutional language of freedom of expression.

In depicting the city of Mumbai as having multiple histories and layers, Court addresses the implication of humanness in spatiality. As Mignolo points out, human rights become a powerful discursive tool that enables a geopolitical remapping of space, dividing it into the ‘First’ and ‘Third’ worlds, or as in the case of Court, into the slum and the gated community. When Kamble’s protégé and friend, Subodh, visits Vora’s apartment, he must face a predictable scrutiny that Vora does not have to undergo when he barges into the slum, looking for Sharmila Pawar. Thus, the prerogative to occupy is available only to those inhabiting the gated (“casted”) community in what profoundly marks the human politics of space.

The Covid moment

The current historical moment reflects in many ways the construction of humanness posed so profoundly by Tamhane, with the state’s response to the pandemic rendering so many invisible. By manufacturing distress in the migrant crisis, the state has revealed how it is enmeshed in a similar discourse of human rights. Retreating in its familiar neoliberal fashion, the absent state easily forgets the migrant labourer and her slum dwelling, as both occupy the peripheries of urbanness and humanness. The absence of protective gear for Pourakarmika workers and the ruthless neglect of their demands are hauntingly similar to Vasudev Pawar’s condition, reaffirming Court’s interrogations. By showing how the Dalit is absent from the human in human rights, Tamhane’s Court presents us with the pandemic called caste.

In his theorisation, Mignolo does not refute the agency of those who are pushed to the margins of humanness. Rather, he shows how those relegated as non-human actively negotiate power and take part in organised struggle. This renunciation of victimhood is recurrent in the lives of all the Dalits in Court. For instance, despite being incarcerated repeatedly, Narayan Kamble consistently returns to his comrades, participating in performances and the printing and circulation of revolutionary literature. By emphasising the daily resistances of Dalits, Court invokes beautifully the centrality that the Dalit movement accords to dignity and personhood, and indeed, the infectious promise of resistance that no virus can consume.

Achintya Anita Gurumurthy is a student of law

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER