Burkina Faso’s National Council for Emergency Relief and Rehabilitation (CONASUR) found in its August 2020 report that more than a million people have been internally displaced by the upsurge in violence in the country. This figure represents a 100% increase compared to early 2020 when Burkina Faso had 450,000 internally displaced persons. Now, almost 5% of Burkina Faso’s population has fled their homes because of violence. Increase in the number of displaced people was anticipated because in June itself the number of forcibly displaced people had reached 921,000– a 92% increase on 2019.

Large-scale displacement of people has greatly complicated the handling of Covid-19 pandemic since the sudden influx of people into another region has overwhelmed health infrastructures. To take an example, in Kaya – the main city in the Centre-North region – the local population of 130,000 has swelled by the arrival of 100,000 displaced people, who are living in four temporary camps and some makeshift shelters. Due to the unprecedented increase in the local population, the Kaya health facility has become overstretched and strained, providing care to eight times the usual number of patients.

The Origins of Violence

The origins of present-day violence and displacement can be traced back to the establishment of various militant Islamic groups in the country. One of the most prominent of such groups is Ansarul Islam, established by Ibrahim Malam Dicko (who died in 2017) in Soum province (Sahel region) in 2016. The group was formally acknowledged in December 2016 following an attack against a military base in Nassoumbou, carried out jointly with the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). This attack was preceded by another terrorist attack on January 15, 2016, when three Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)-affiliated assailants stormed the popular Splendid Hotel and nearby Cappuccino Café in Ouagadougou, opening fire, killing 30 people and wounding 71 others.

Dicko’s real name was Boureima Dicko and he was born into a family of Muslim preachers in Soboulé, in the province of Soum. In 2009, he began preaching in villages in Soum and on two popular radio stations, La Voix du Soum and La radio lutte contre la désertification (LRCD). Dicko’s rhetoric was composed of messages of social equality and discursively destabilized the dominance of traditional chiefs. His anti-establishment rhetoric ideologically impacted the historically marginalized Fulani/Peul and Remaibe communities in northern Burkina Faso who saw him as a protector of the poor and a vocal critic of the West’s hegemony.

While Ansarul Islam was fuelled by local resentments, it is also a product of various structural conditions. To understand the structural situatedness of terrorism in Burkina Faso, two points need to be comprehended. Firstly, in 1995, President Blaise Compaoré had created the elite corps Régiment de Sécurité Présidentielle (RSP) and put it under the leadership of Gilbert Diendiéré. The elite unit was lavishly funded, its personnel received high-grade training and were rewarded with spoils from the regime’s business in Burkina Faso and foreign countries. In a nutshell, the military unit and the president together constituted an elitist coterie interested in self-enrichment. RSP and Compaoré were specifically interested in Mali where involvement in the drug trafficking that crossed through the Sahel-Sahara, originating in the Gulf of Guinea and ending in Europe, promised many riches. In order to benefit from drug trafficking, the RSP stopped policing the trade exchanges and instead, colluded with traffickers by offering transit corridors against payment. By protecting drug trafficking, Compaoré’s coterie compromised a key security agency and created a conducive environment for terrorist operations.

Secondly, in 2012, ethnic Tuareg soldiers and jihadists had armed themselves with weapons from Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s looted arsenals and entered northern Mali. Many of these Tuareg soldiers formed the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) which launched an armed rebellion in January 2012. Years of neoliberal reforms and centralized control from a tone-deaf government in Mali’s southern capital of Bamako had left many northerners impoverished and dissatisfied. Therefore, in a matter of weeks, the rebels had conquered an area the size of Britain. The Tuareg soldiers were soon joined by Salafist groups that had been based across the Azawad (a stretch of Saharan land east of Timbuktu) since the early 2000s. In response to these developments, France established a special-forces base in Ouagadougou in 2010 and decided to contain the Salafists through collaboration with the Tuareg rebels. This French approach planted antagonisms between the Burkinabe state and Salafists since the latter saw the former as an opposing entity facilitating the extermination of Salafists by providing military bases to France. Currently, one can see the eruption of Salafist opposition against the Burkinabe state as Ansarul Islam – which is a Salafi organization – plunges the country into a seemingly unending conflict. As Ansarul Islam is a corollary of myriad structural conditions, it possesses transnational linkages with various other groups. Dicko had built ties to the Macina Liberation Front (FLM, or Katiba Macina), one of the many al-Qaeda-linked groups in the Sahel, which in 2017 merged with Ansar Dine, AQIM and al-Mourabitoun to form the umbrella group Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).

Since the official institution of Ansarul Islam, killings and attacks have greatly accelerated. Between January and May 2019, Burkina was the third highest-ranking country in the world in fatalities from civilian targeting, with 670 casualties, following Syria and Nigeria. In comparison to 2018, civilian fatalities rose 7,000% in Burkina Faso in 2019. According to UN figures, there has been a fivefold increase in the number of attacks in Burkina Faso between 2016 and 2020 with terrorism’s toll increasing from 80 lives per year to more than 1800 in the same period. Violence has reached such a level that on 11 August, 2020, Genocide Watch published an article where it recognized the violence in Burkina Faso as Stage 9: “Extermination”.

A Flawed Counterterrorist Strategy

In response to terrorism in Burkina Faso, a highly flawed and militarized strategy has been adopted by the Burkinabe state and other imperial powers. France, for instance, has shown interest in the Sahelian region and according to a white book released in 2013, “The Sahelian strip, from the Atlantic to Somalia, appears to be the geometrical locus of intertwined threats and, consequently, requires specific vigilance and investments in the long run”. Here, France considered “vigilance” and “investments” to be synonymous with the pure militarization of counterrorism.

In 2014, France’s Mali-focused Operation Serval transformed into a regional force codenamed ‘Barkhane’, charged with counterterrorism activity in five Sahelian countries: Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger. These five countries covered by Barkhane joined forces to form a regional security body, the ‘G5 Sahel’, with the aim of providing security for their populations. The G5 Sahel launched its Joint Force (Operation Barkhane), based in Bamako in Mali, in 2017 and also has a Defense Academy in Nouakchott in Mauritania which aims to train the future military leaders of the task force. As part of the operation, four permanent bases have been established: an intelligence base in Niger’s capital Niamey, a regional base in Gao of northern Mali, a special forces base in Burkina Faso’s capital Ouagadougou, and an HQ/air force base in Chad’s capital of N’Djamena for a total of about 5,000 French soldiers in the region.

The Joint Force fights terrorism and organized crime in three main areas: the Liptako-Gourma zone (between Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger), along the Mali-Mauritania border, and along the Niger-Chad border. Operation Barkhane is the largest French military operation abroad and costs $685 million a year, 50% of the French security and defense cooperation budget worldwide. In February 2020, France bolstered the already large military capacity of G5 Sahel by adding 600 troops to its 4,500-strong operation in five countries in the region. This military reinforcement came on top of the deployment of 200 additional troops in the region in January, 2020.

France’s militarized tactics have proved to counter-productive. In 2019, in the five countries where France intervenes, jihadist groups strengthened their geographical reach than in 2013 and the fatalities caused by war also increased. Chérif Moumina Sy, the defense minister of Burkina Faso, was forced to say, “The G5 Sahel is not effective at all”. On top of having counter-productive effects, G5 Sahel has resulted in an increasingly aggressive behavior on the part of Burkinabe forces who have been killing three times more civilians than jihadists. During the first seven months of 2020, 288 civilians have been killed by government forces, more than a quarter of the total civilian deaths caused by violence. In Burkina Faso’s east, the number of civilians killed by government forces has swelled by almost nine times so far this year compared to the second half of last year.

In June 2020, twelve men were arrested by the Burkinabe forces from their home in Tawalbougou. Of the twelve that were taken, only five survived the encounter. Six of the men were shot during the interrogations and another died due to the beatings that he suffered. The remaining five have reported that they were tortured during the interrogations. According to the men, they were taken because the army believed that they were linked to Islamic extremist groups. Contrary to these claims, the men have claimed that they have no affiliations to any jihadist organizations.

Between November 2019 and June 2020, at least 180 bodies were found in mass graves in northern Burkina Faso with evidence suggesting government forces’ involvement. The majority of the dead were found by residents within 5km of the government-controlled town of Djibo and many of the carcasses were blindfolded, had their hands tied up and were shot in the head. These findings were part of a comprehensive report produced by Human Rights Watch which documented the detention and execution of 116 men and adolescents by security forces between September 2018 and February 2020.

In spite of the excesses committed by Burkinabe state forces, France has not stopped militarily consolidating the armed forces. In fact, it has tacitly supported the violence by not condemning the attempts made by the military to ensure impunity for their actions. The National Assembly of Burkina Faso passed a law in 2019 that prohibited the “demoralization” of Burkinabe state forces. Through this law, human rights groups’ reporting on the military’s conduct has been hindered since the disclosure of killings is considered an attempt to “demoralize” the forces. All this while, France has remained silent.

USA, too, has been engaged in securitizing Burkina Faso along with France. The motivations behind these military efforts have been made clear by United States Africa Command (USAFRICOM) which states that jihadist violence in Niger, Burkina Faso, and Mali has “the potential to spread through the region and impact Western interests.” To protect “Western interests”, the US has been involved in training the Burkina Faso armed forces. US military training sessions run for two weeks and include 30 people from the army and police. The men are trained by up to 20 Americans. Furthermore, the American Special Forces Operational Detachment provides advice and support to the 11th Special Intervention Battalion which is conducting operations in the tri-border region between Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. In addition to training and advice, US military built presence in Burkina Faso in 2007 when it signed a deal that enabled the Pentagon to establish a Joint Special Operations Air Detachment in Ouagadougou. By the end of 2009, about 65 U.S. military personnel and contractors were working in Burkina Faso, more than in all but three other African countries, according to a U.S. Embassy cable from Ouagadougou.

Imperialism in Burkina Faso

The implementation of a militaristic counterterrorist strategy by France and USA only seeks to hide the deeper causes of terrorism which are rooted in imperialism. Through the imperialist subordination of Burkina Faso to metropolitan capital, the African country is being pillaged and underdeveloped. France’s monetary policies in Burkina Faso and other African states serve as an important example through which we can understand the dynamics of imperialism in the region.

The CFA franc, the French empire’s colonial currency, was officially created on 26 December 1945 by a decree of General de Gaulle. With the institution of the CFA franc, a fixed rate of exchange with the euro was set at 1 euro = 655.957 CFA franc; two central banks – the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) and the Bank of Central African States (BEAC) – were required to deposit 50% of their foreign exchange reserves in a special French Treasury ‘operating account’; and full freedom of movement was given to flows of capital and income. These measures have proved to be inimical to African countries such as Burkina Faso.

- France holds a de facto veto on the boards of the two central banks within the CFA franc zone. The president of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WEAMU) Commission attends only in an advisory capacity. This means that the monetary sovereignty of African countries has been subverted by western powers and now, neoliberal monetary orthodoxy, with its anti-inflationist bias, dictates the policies of the African Third World. African countries’ subordination by anti-inflationist policies forces them to keep the interest rate high and constrain credit expansion. To do the latter, total credit to government is strictly limited to 20% of the previous year’s fiscal receipts. Therefore, the credit-to-GDP ratio stands around 25% to 13% for franc zone countries but averages 60%+ for sub-Saharan Africa, and 100%+ for South Africa. Production capabilities are closely tied to the amount of credit available from the banking sector and the limitation of the volume of internal bank credit to states, households and small and medium-sized enterprises heavily impacts local entrepreneurs.

- The centralization of African foreign exchange reserves in the hands of the French treasury has translated into monetary imperialism wherein the treasury has often offered negative interest rates for African exchange reserves. This means that BCEAO and the BEAC have been losing money by storing their foreign reserves in the French Treasury. The money stolen by France has been used in a variety of ways and many believe that the reserves made up a part of the French contribution to the loans given to failing Eurozone countries during the financial crash in 2008. Opposing France’s theft-like policies, the president of Chad Idriss Déby had stated at the 55th independence celebrations: “Why do all exchanges go through the Bank of France? What do we gain by putting our resources into trading accounts. What is the interest rate we earn?”

- CFA franc has acted as a barrier to industrialization and structural transformation of African economies. 11 of the 15 members of the franc zone are classified as Least Developed Countries (LDCs), while the remaining countries (Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Congo, Gabon) have all experienced economic decline. The colonial currency was overvalued from the beginning and this overvaluation coerced the countries into becoming primary commodity exporters and net importers. France has greatly benefitted from the primarization of African economies since this has translated into trade surplus with regard to those franc zone countries and consequently, the maintenance of substantial foreign exchange reserves. Many a times, exchange rate overvaluation has proved to be destabilizing for an entire occupational sector. To take an example, in the mid-2000s, the cotton sector in Burkina Faso was making heavy losses due to the appreciation of the euro. Between October 26, 2000 and July 15, 2008, the euro appreciated more than 90%. This meant a huge loss of competitiveness during this period for Burkina Faso whose cotton sector was no longer profitable at the parity then observed between the euro and dollar.

- Free capital mobility within the franc zone has allowed French companies to repatriate their profits and thus, under-develop the African economies. Free transfer of incomes and capital facilitates the drain of economic surpluses from the colonies to the metropolis and creates an environment where French capital can invest and disinvest freely. In the words of Samir Amin, when “the commercial banks [in the franc zone] are foreign owned and are authorized to transfer funds in and out of the country without being subject to any control, the national authorities are bereft of all means of using the basic instruments of monetary policy.”

The discontent produced as a result of imperialism provides a fertile ground for the growth of terrorist organizations. In Burkina Faso, militant Islamic organizations were able to emotionally exploit the disgruntlement with the strong-arm tactics of imperialism to rupture the sovereignty of state. By not addressing the root of terrorism and choosing to militarize the country, imperial powers will only perpetuate the state of permanent war in Burkina Faso.

Rolling Back Militarism

As per analysts, the Covid-19 pandemic in Burkina Faso can lead to the following changes: economic growth could drop from 5.7% in 2019 to a range between 1.38% and -1.75 percent in 2020; the unemployment is expected to grow up to 5.92%; export of extraction products will contract by 6% and the export of agricultural products will contract by 16%.

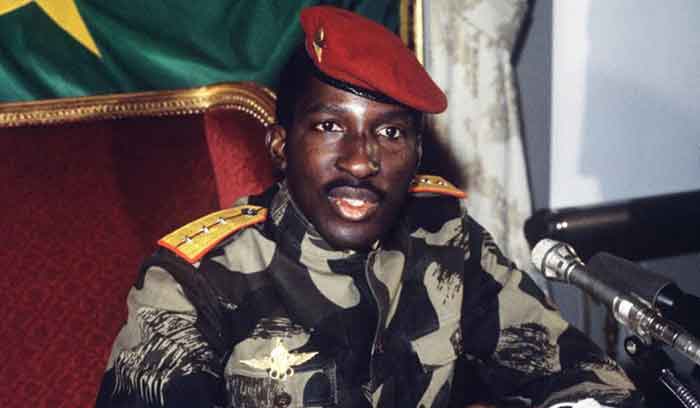

Burkina Faso’s economic distress will get further aggravated by the aggressive policy of core capitalist nations which tout “War on Terror” as the panacea to the ills of imperialism. Since American and French policies are based on imperialist exploitation, they are incapable of effectively ending terrorism and reconstructing Burkina Faso. Those nations can only further militarism and tear apart the socio-economic fabric of subjugated countries. In the current conjuncture, the application of the “War on Terror” policy in Burkina Faso needs to be resolutely opposed by the international community and an anti-imperialist stance needs to be adopted. The power of anti-imperialism was succinctly expressed by Thomas Sankara, the revolutionary leader of Burkina Faso, who had said: “When the people stand up, imperialism trembles”.

Yanis Iqbal is an independent journalist

Originally published in LA Progressive

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER