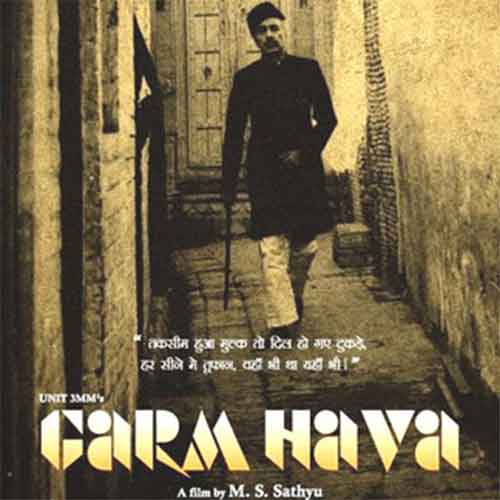

Mysore Shrinivas Sathyu, who turned ninety on July 6 this year, is an important figure in the annals of New Indian Cinema by virtue of just one film- Garam Hawa (Hot Winds, 1974), a scathing dissection of the diseased mentalities that caused the Partition of the country (read, Partition of Bengal and Punjab). Garam Hawa achieves its purpose by portraying the repeated tragedies that befall one Salim Mirza ( played memorably by Balraj Sahni in what turned out to be his last outing) and his family, but which cannot rob them of their humanity, or their confidence to stay on in a badly ravaged Agra, post-1947, where generations of Mirzas had lived before the blow fell.

Speaking in the mid-1970’s, at the height of energetic discussions across the country on his debut film, Sathyu observed: “ What I really wanted to expose in Garam Hawa was the games that politicians play. Actually, there are no human considerations at all. I am not talking only about India, but even in Vietnam, Biafra, Germany….it is all the same. How many of us really wanted the Partition? Look at all the suffering it caused.

Perhaps, Sathyu had no premonition of the furor that Garam Hawa would cause on its theatrical release. In certain circles, the film was made out to be pro-Muslim, and its director was accused of fishing in troubled waters. But the reality was quite different: not only had Sathyu shown a unique cinematic vision and narrative skills of a high order, but been scrupulously fair in his interpretation of the socio-political circumstances of the time.

Replying to the charges brought against him by elements whose ideological children were to corner political power in Delhi years later, Sathyu argued: “I am not denying that the Hindus, too, have suffered under Muslim rule. It is an age-old wound that has been carried on and on, but nobody wants to talk about it. You want to hush it up, to pretend it doesn’t exist. Unless you discuss it openly and try to understand the problems, you are not going to solve it by just hiding it”.

The director couldn’t have put it better. In its own way, Garam Hawa was being faithful to the principal aspiration in the manifesto of New India Cinema – namely, to forge new paths in terms of vibrant art and truthful politics. Made more than a quarter of century after independence, the film sought to do away with many of the falsehoods that had came to be lodged in both the folklore and the partisan history of liberation from British rule. The unfair demonization of Muslims being solely responsible for the vivisection of the sub-continent needed to be seriously attended to. And this was done remarkably well in artistic terms by Sathyu. The national award for integration that the film got represented the highest recognition that it could possibly have received.

The friendship between the besieged shoe-maker Mirza and his well-off Hindu neighbor (played with characteristic feeling by A.K.Hangal) – a friendship that has no use for the evil that transpires all around them in the name of ‘patriotism’ or ‘separate identities’ – is one of the pivots on which the film’s storytelling, or indeed its politics of accommodation, rests. As Attia Hossain, the novelist wrote at the time of the film’s release: “The tragic content of Garam Hawa becomes a classic document of human dignity against the inhuman aspects of historical events.”

If the worth of a work of art lies in its ability to withstand the test of time, it goes without saying that Garam Hawa passes that test admirably well. Almost fifty years after its making when we see it today, there are many who feel the same turbulence of spirit or the same compassion for its undeserved victims that we experienced at our first viewing. The universalism of the film’s theme and the passion with which it had been fleshed out, made a critic write: “Remarkably mature both politically and cinematically, Garam Hawa is directed with rare delicacy. Several scenes – notably the death of the old grandmother, at last recapturing her lost memories of her wedding day so long ago – are worthy of Satyajit Ray.”

Here, an interpretation is perhaps called for. While Ray’s appreciation of Garam Hawa is there for all to read in his well-known book of essays, Our Films, Their Films, Iqbal Masud, the eminent critic and a Ray admirer himself, was not so sure about his fondness for the film. While remarking that Satyu’s debut called for serious notice, Masud found himself not so happy with some of the more sentimental passages in the film.

Be that as it may, Garam Hawa, based on a short story by the renowned modernist Urdu writer, Ismat Chugtai, is, by common consent, one of the more creative and insightful denunciations on celluloid of the tragedy of Partition, engineered by the watchful, malevolent-midwife eyes of the departing British. When such a holocaust descends on a country, no doubt many individuals suffer for no fault of theirs, but, simultaneously, a few grow stronger in their resolve not to give into the forces of dehumanization. Salim Mirza and his graduate-son Sikander (played by Farooque Sheikh) are to be counted among those who refuse to be demoralized by the tragic turn of event in their lives, or see themselves in the role of the ‘victim’. Rather, their actions show hat they, especially Sikander, are firmly rooted in the belief that flight to an alien land to escape the trials in one’s own, is not for them. Attia Hossain rightly points out: “Sathyu’s Salim is restrained, dignified, compassionate, and committed.” In other words, qualities least expected of someone who has lost his young daughter, his flourishing business, his ancestral haveli, and a succession of departing, Pakistan-bound relatives, to an overwhelming turn of history in the face of which he is helpless, like millions of others, but far from defeated.

In the end, Garam Hawa signifies the triumph of humanity and hope over despair and empty rhetoric. If Sathyu failed to make another film that came anywhere near Garam Hawa in terms of art or politics, the principal reason for it could be that it is difficult, if not impossible, to repeat a masterpiece.

*** *** ***

Since long, fictional cinema has been used by filmmakers the world over to reflect, among other things, working class realities as an integral part of the total human experience. Garam Hawa is set in that precarious period when thousands of North Indian Muslims went over to West Pakistan while many times that number chose to stay back in what had for generations been their home and hearth. Jinnah’s two-nation theory did not appeal to those who decided to stay back, meaning children-of-the-soil- like Salim Mirza. This is the religio-socio-political background of the film.

However, there is an equally important aspect that Sathyu can be said to have explored, namely, the economic-working class aspect. Focusing on the compulsions of earning one’s daily bread by the sweat of one’s brow, especially in a time of violence and calculated mischief-making, the director, in his own almost unobtrusive way, sought to portray laboring lives as a mixture of despair and some defiance.

Salim Mirza, or his son, Sikander, are the kind of proud citizens of whom the working-class movement in any land/society/community would be rightly proud of. Mirza is a small shoemaker who plies his trade with the help of bank loans and the cooperation of a handful of devoted workers. He is not rich, but earns enough to live in reasonable comfort with his family in their ancestral haveli. But partition sees to it that bank loans are denied even to honest and honourable people like him; every Muslim is an object of suspicion, likely to run away to Pakistan without repaying the money they had taken.

On the one hand, Mirza’s business languishes; on the other, his relatives leave one after another for Pakistan on one pretext or the other. Family tragedies do not spare him either. In the end, he is left with just his wife and his unmarried younger son, Sikander, a jobless graduate. Contrary to advice from all and sundry, Sikander decides on staying back and carving out a place for himself in the midst of the surrounding prejudice and anarchy.

In this regard, a sequence showing Sikander and his Sikh and Hindu friends, all jobless like him, having tea in a wayside stall, deserves special notice. When Sikander is sarcastically advised by one of his friends to go to Pakistan where jobs would be easy to come by for a person like him, the former is provoked enough to strike back immediately, saying he has as much right as anybody else to stay where he is and demand his right to suitable employment in the land of his birth. Needless to emphasize, this is a telling sequence fraught with many meanings around class and religious identities in particular. However, witnessing this sequence in India of 2020 when social and political degeneration appear to have reached rock-bottom, the right to work and gainful employment that it talks of, sounds almost farcical.

Tragically, at the moment of writing when the country is writhing under the punishing wheels of the majoritarian juggernaut, many a right which should have been automatically available to the large Muslim minority is being questioned, and even outright denied in a manner reminiscent of the times in which Garam Hawa is set. In fact, many Sikander of today is having an even tougher time than that faced by the rightly-spirited predecessor in Sathyu’s film. In the circumstances, it is not uncommon these days to hear the lament that their ancestors were wrong in turning a deaf ear to Jinnah.

Garam Hawa ends on a note of dramatic protest. If it looks didactic to some viewers, perhaps they need to be told that the protest is only following the logic of the tale. In a significant twist, the father learns from the son that running away from problems, be they of the religious, economic, or any other kind, can provide no lasting solution. Rather, life’s fulfillment is in proving equal, if not superior, to the struggle. Eminently befitting the theme, the closing frames of Garam Hawa show the young and the old, or the experienced and the energetic, all coming together under an inquilabi banner in a procession drawn from all sections of society asking for the right to work; the right to earn a decent living in return for hard labour; and, finally, the right to live with honour and in peace with one’s fellows.

Hope, they say, is the most insistent, the most persistent of all our desires. Even in the most hopeless of situations, strugglers and sufferers have been known not to abandon hope. At a time when the working class movement is, sadly, but a faint shadow of what it was even thirty years ago, having fallen victim to contradictions of diverse kinds combined with relentless assaults by corporate and their protectors in the State machinery, the shining examples of Salim Mirza and Sikander, if recalled with deserved seriousness, could serve as a source of hope and confidence.

Salim Mirza is no doubt an employer, in the sense that a handful of workers take orders from him and are paid by him, but the profit motive in his case never reaches the point of excessive self-interest. True, it can be imagined, that Mirza’s employees do not eat as well as he does or live as comfortably, but neither do they waste away in hunger, which is very often the case with trader-worker relationships in our country. Moreover, the kind of respect that Mirza gets from his workers cannot happen without some amount of sacrifice on the part of the employer himself.

Another point worth considering is that Salim Mirza never regards himself as superior to his employees. If he has any airs, they are those of gentle, cultured relic of a past fading out in the wake of religious animosities with underpinnings of material interest. When his small workshop, resembling a humble cottage industry more than a serious business proposition, is gutted in a fire caused by rioters, the man of patrician looks and delivery does not consider it beneath his station to squat on the floor with his workers and handle the tools of the trade in an exemplary collective effort to make the business stand once more on its feet. Clad in a lungi and a similarly humble upper garment, Mirza effortlessly gets down on his haunches and sets to work in a comradely fashion to defeat the vicissitudes of fortune (read, the conspiracies of history) affecting him, his family, no less his workers and their families. In a revelatory reversal of roles, the fateful trajectory connecting yesterday’s employer to today’s worker of sorts is established. However, it would be naïve at best and suicidal at worst (at least for the working man) to read in the scene the possibility of a discourse negating theorizings relating to the inevitability of conflict of interests between different classes or, more precisely, between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’.

In bits and snatches such as the above sequence, Sathyu’s progressive politics is revealed. However, it is in the procession sequence with which Garam Hawa ends, that one daresay, the director’s social philosophy comes to the fullest view. It is common knowledge that following partition, the condition of the job market was extremely distressing, but particularly for those Muslims who decided to stay put and make a fresh beginning in the land of their ancestors. For Muslims living in the Hindi-speaking heartland, like the Mirzas, it was a particularly difficult choice to make – should they migrate to a new country almost wholly composed of fellow-religionists and promising better prospects of physical safety and professional success, or continue to live in their traditional homeland clouded by the spectre of accusations of being ‘the enemy within’.

It is in this background that the plight of Salim Mirza and his family, reduced to just three by death, migration, or the evaporization of hope in the breasts of the less-than-stout, may be seen. The Mirzas had been inhabitants of Agra for generations together, visibly blessed with some amount of property, education, and social standing. Given the prevalent conditions, it was inevitable that they would be viewed with suspicion, along with other Muslim families that saw no reason to opt for Pakistan. That, despite such formidable odds, Sikander should dare to demand proper employment in free India as a matter of right, demand it openly and stridently along with the educated unemployed belonging to other religious communities, should serve as a source of inspiration to those young Indians who find themselves in a similar position today. With artistic vision and social insight, Garam Hawa not only identified several key working-class realities, but suggested how problems arising from these realities could be faced with honour and courage.

Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER