The 24th edition of the Kolkata international film festival, held in November 2018, showed a surprisingly large number of films from Australia, which has never been counted among the foremost film-making nations of the world; no less than two dozen in all. It is hard to tell whether the ‘focus’ had anything to do with an increasing interest in Down Under on the part of Indian students, professionals, or corporates like the Tatas and the Adanis.

To understand why just a couple of the films on view had anything to do with the aboriginal experience in that country, perhaps one should know the history of genocide and usurpation that made for the existence of ‘white’ Australia. In this context, my mind goes back to the year 1987; even as Australia was preparing to celebrate 200 years of white settlement, oppression of aboriginals – the original people of the vast, never-never island – continued apace. The oppression is naked and heartless in outback settlements, but exists in subtle (and sometimes in not so subtle) forms in the towns and cities as well.

A news agency report dating back to that year speaks of a high court judge who wept as he listened to harrowing accounts of racism and denial of justice to aborigines in a remote New South Wales community. The judge wept and said: “I have been to Soweto in South Africa, to German concentration camps, but this is my own country.”

Despite an occasional admission such as this, not many white Australians seem willing to face the truth that colonization has done little good to the indigenous population. White Australians are yet to acknowledge in large numbers that prejudice against the remaining approximately 150,000 aborigines is rife. Unlike recent arrivals from Asia and Europe, many of whom are more than comfortable in the role of the comprador, the aborigines have never been integrated into the mainstream of Australian society. In these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that the aboriginal issue should be calculatedly glossed over, as in the package of films put together by an Australian citizen of Bengali origin.

People blessed with even a reasonably dependable memory will remember that at the time of the Sydney Olympics in the year 2000, a section of Australia’s original inhabitants put up protest demonstrations to draw the attention of the international community to their plight. The protests drew inspiration from the example of the iconic aboriginal athlete Cathy Freeman, who had repeatedly gone to the media with complaints of how badly her community is treated in a country that never ceases to speak of equal opportunities for all. As was to be expected, in many places the protests faced water cannons and burly, baton-wielding police forces.

Geoff Clark, head of the country’s most powerful indigenous group, said at that time: “We’ve been the subject of mental torture and violence in this country for 200 years… Sport and politics do mix. Our hope is for ‘black gold’ (meaning Freeman winning the gold medal in 400 meter sprint, which she did).” Another aboriginal leader Charles Perkins, grabbed international attention when he threatened that Games visitors “would see burning cars and burning buildings”. Perkins later admitted that his comments were fueled by decades of frustration at the mistreatment of his people, and spoke of only peaceful protests.

For those who care to know, aborigines make for just two percent of Australia’s roughly 20 million population, and are the country’s most disadvantaged group. Even official figures cannot escape showing that aborigines suffer the highest levels of social and economic disadvantage, as well as markedly higher death and incarceration rates. Again, forced removal of aboriginal children from their families – a former government assimilation policy – ended in the 1970s, but also led to the so-called ‘stolen generations’.

It was in Sydney where Australia’s history of white settlement began as a British penal colony in 1787. White Australia has engineered things in such an ingenious manner as to make invisible to the world, the fact that aboriginal settlement stretches back to at least 40,000 years. Stressing the appropriateness of the Summer Olympics being held in Sydney, Clark had said: “This was the place of the first dispossession, the first raids, the first removal of children. This was the place of the first resistance, it was the first demonstration of our will to survive…”

Mervyn Hardinge, a Calcutta journalist of Anglo-Indian lineage who migrated to Australia and used to write a respected column for The Statesman, struck a discordant note even as the loud-mouthed, drink-sodden Australian prime minister of the 1980s, Bob Hawke, claimed: “Australia is one of the most remarkable experiments in nation-building.”

Hardinge observed at a time of wild celebrations to mark 200 years of white settlement: “For the more thoughtful, the melancholy fact remains that January 26, 1787, marked not only the establishment of a convict colony, but the beginning of the dispossession of the aboriginal from his own land and the destruction of a culture… It might be in order at this point to say that one of the purposes of the protest march was to bring to notice the inquiry now being conducted into the deaths of aboriginals in police custody, of which there have been a startling number in recent months.” The thrust of Hardinge’s observation was of a piece with what the aborigine leader, the Reverend Charles Harris, had to say: “We have been victims of apartheid for 200 years.”

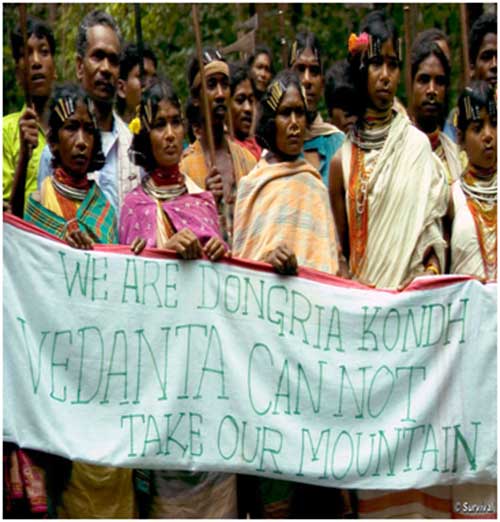

Nearer home, the Adivasis in our own country are faced with a similar spectre of being denied their basic rights to jal (water), jungle (forests) and jamin (land); to traditional lifestyles; and to a socio-cultural identity quite different from that of the ‘outsider’ (diku). Everywhere, the Adivasis are dispossessed, displaced, pauperized, often by official decree. But the truly remarkable thing is that, everywhere, they are defying as best as they can the arson and anarchy imposed on them by waves of guns and governments.

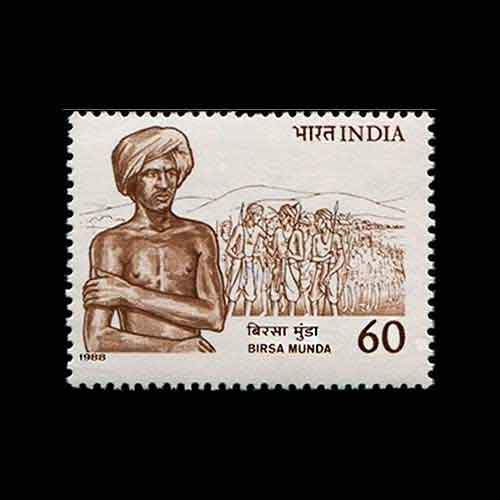

When the genuine Adivasi activist raises his voice in protest, or the Adivasi mother in, say Chotanagpur or the Santhal Parganas, tries to put her child to sleep with a lullaby about the martyred hero, Birsa Munda (1874 -1900), they are in effect echoing the words of their compatriot, the Australian aboriginal leader, Mick Miller, who complained of being “truly strangers in our own home… we are living on the fringes of a white, affluent society, treated as fourth and fifth-class citizens.”

( Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.)

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER