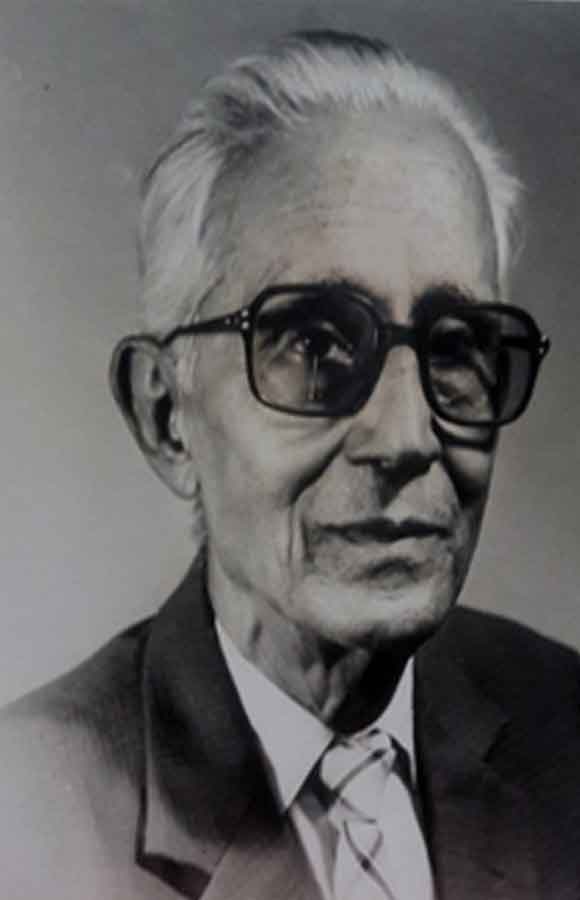

When I was a boy I once heard my father wondering to my mother why “a day did not have more than twenty-four hours”. I know it is difficult to believe, but it is a fact that my father spent several decades of his life working fourteen to sixteen hours a day. When he ate, slept or relaxed, only he and his gods knew. Half his waking hours was spent in the chemical laboratory of Tisco from where he retired as a junior chemist; the other half was devoted to collecting and sending news to agencies, notably the Press Trust of India (PTI); to daily papers (first Hindustan Standard, and later Amrita Bazar Patrika); and to Current, the well-known Bombay weekly edited by D.F.Karaka. These publications have gone the way of all newsprint, but not before leaving their impress on many a mind.

Job satisfaction is something that we all seek; or, at any rate, ought to. If the work we do, brings no pleasure or excitement with it, it gradually turns us into machines listlessly following a set of rules, a list of do’s and dont’s. It did not require intelligence of a high order to realize that my father drew his sustenance from his family and from journalism. His heart was never in his Tisco job which, I guess, was kind of a torture to him. However, it had to be done because of daal-bhaat considerations. I am almost certain that my father’s heart beat faster at press conferences and at the telegraph office. This despite the fact that there was hardly any money in journalism in those days. Then why did a handful of gifted and hard-working people who could have ‘done better’ elsewhere, gravitate to it? Mystery of mysteries! Devi Chatterjee or N.K.Sane (of The Democrat) of Jamshedpur, N.N.Sengupta of Ranchi (of The New Republic fame), or Hirendranath Chatterjee of Dhanbad (synonymous with the Jharia-Raniganj coal-belt who gave the region its first trade journal, The Coalfield Times) kept their respective pens going for as long as destiny allowed them to, because a big part of their heart and their mind belonged to the Fourth Estate.

If the quest for honour and excellence which was the hallmark of their professional lives is conspicuously absent in the ranks of today’s journalists, it only goes to show how far times have changed and standards have fallen. There are some who say that comparisons are odious, but then, there are others who will never cease to compare if for no other reason than to comment on the steep decline that has come to attend our lives in practically every aspect.

Father, in whose footsteps I followed as a journalist, was often given to telling me to do my job as best as I could or not do it at all. He would say, “Don’t write for paanwallahs.” Not that he had a low opinion of paan-sellers, it was his way of advising me to scrupulously avoid bazaar gossip – the shallow and the frivolous. “The Statesman is The Statesman not for nothing; readers rely on it because they know that the news it carries are checked and double-checked – they are factual, not fabricated as is often the case with its contemporaries.” However, he would make it clear that views and comments is something entirely different. It is a matter of great pride and satisfaction to me that he religiously practised the strictures he laid down for me. In the process, he ran into serious trouble more than once with corporate and other demons, but it seemed to me that he derived a certain contentment in facing certain difficulties in the pursuit of his professional duties.“Don’t compromise on quality, and certainly not on truth” –my mentor’s words still ring in my ears.

Father used to say that his insignificant Tisco job gave him the money needed to run the family, but it was PTI, Amrita Bazar Patrika, Durga Das’s Indian News and Feature Alliance (INFA), or Nikhil Chakravartty’s India Press Agency (IPA) that gave him an identity worth having. In the period ’fifties to the ’seventies, there was no politician, bureaucrat, labour leader, industrial executive or social butterfly who did not know him personally in erstwhile Bihar, or whom he did not know well. Many a man-in-the-street, too, figured prominently in his list of friends and acquaintances. He felt that a journalist of all people could not afford to neglect anyone, least of all the seemingly powerless common man, because everyone, big or small, was a potential source of news; of facts and figures that mattered. The net result of this belief unerringly practised by him was that it was difficult to find a more popular figure than him in the Jamshedpur landscape.

INFA or IPA could not pay father much, but he kept sending them news and features for years because he felt that together, he and the news agencies were playing an important social role – keeping readers informed about what was happening in and around the Jamshedpur industrial zone. One thing to note about the despatches he sent was that these invariably had a pro-working class slant. Owing to his proximity to important INTUC leaders like Professor Abdul Bari, a firebrand and conscientious objector if ever there was one, and Michael John, or AITUC veterans like Kedar Das, Dr. Udaykar Misra, Barin De or Sunil Mukherjee (all associated with the historic 1958 strike by Jamshedpur’s steel workers), father was able to score many a ‘scoop’ relating to labour unrest, or tripartite negotiations between union, management and government on bonus and other vital issues. His uncanny expertise in flashing such news nationwide before his press colleagues had even an inkling of what was happening around them, earned him an enviable reputation as a resourceful and reliable newshound. However, he relished competition and would never fail to admire someone if the latter beat him to the tape. In this connection it would be in order to mention the high regard he had for the professional acumen consistently shown by The Statesman ‘staffer’ in Jamshedpur, Deoki Nandan Singh, who died prematurely, or for N.N.Sengupta, the founder-editor of The New Republic who, too, passed away in his prime. I remember father speaking highly of Mr. Sengupta’s editorials, especially those on tribal affairs.

Father could not have been happy with the fate that his despatches sometimes suffered at the hands of big-city sub-editors who clearly thought no end of themselves. At times, the very spirit of a newsitem would be so altered in the name of ‘subbing’ that he would wring his hands in despair. The stickler for accuracy that he was, he would suffer acutely. Years later in the ’seventies when I worked for a short while as a sub-editor in the head office of one of the country’s leading daily papers, I saw with my own eyes how nonchalantly some of the senior ‘subs’ went about mauling ‘a copy’ painstakingly sent out by an accredited ‘stringer’ in some mofussil town. Remembering my father’s anguish, I made it a point to be respectful to reports sent out by small-town correspondents. As I saw it, the humble ‘airport correspondent’ or ‘legal reporter’ deserved to be taken as seriously as seasoned campaigners reporting from London, Washington DC, Tokyo or Beirut.

I would be failing in my duty if, at this point, I were not to devote a few words to an unforgettable trainer of sub-editors by the name of Jiten Sen who I had the good fortune of meeting at the newspaper office mentioned earlier. In the space of just a few weeks, Jiten Sen taught me and three fellow-probationary ‘subs’ the essentials of subbing so thoroughly that I remember his lessons clearly to this day. A friend and associate of Jayaprakash Narayan and B.P.Koirala, the Nepali Congress leader, Jiten Sen was also a fantastic story-teller who regaled us once with the saga of how King Tribhuvan of Nepal fled to India in the face of grave danger to himself and his family in Kathmandu. Memories of this aged man with a wry sense of humour and impeccable knowledge of how English was to be spoken and written are still vivid in my mind.

In the closing months of the year 1972, father would often go into a huddle with his three sons about the possibility of starting a ‘viewspaper’ from Jamshedpur which would ideally cover industry, especially steel and heavy engineering, politics, social affairs, literature and the arts. There were several reasons for his wanting to start what began under the name Panorama but had to switch over after some issues to Motif following a government instruction asking for a renaming. The primary reason for his wanting to start a paper was that he thought that a city of Jamshedpur’s size and importance deserved at least one serious publication which would attend to the problems of the place and its potential to do better. If he had the resources, perhaps father would have gone in for a daily, but since he did not possess even a minute fraction of what was required to embark on such an expensive project, he did the next best thing he could have done in the circumstances – he founded a weekly. The other important reason to start the weekly was that he wanted to be as free and effective as possible in his twin tasks of reporting and editorializing. Having worked under others not always with satisfactory results, he knew very well the limits to free expression that would be suddenly imposed by higher-ups who always seemed to know better. If he had his own paper, he told himself and his sons, he would be able to write whatever he thought was in the best interest of the community.

Surprisingly, the encouragement he got whilst he was still thinking about his ‘dream child’ came not from me – a journalist, like his father – but from his other two sons, one an engineer and the other an architect. My two elder brothers gave our father the solid emotional and psychological support that he was perhaps looking for and which, doubtless, he deserved. It was only after some time that I fell in line and began to do what was expected of me. If I was initially hesitant in throwing my weight, for what it was worth, behind the idea of the weekly, it was because I had seen more than one journalistic or literary venture wither away for want of public support even in such a large and comparatively enlightened place as Calcutta.

For as long as it lived, that is, from January 1, 1973, to December 31, 2007, Motif carried the stamp of my father’s personality – his attitudes and his aspirations, his concerns and his commitments. Perhaps it would be correct to say that his personality was influenced in measure big and small by the substance of some remarkable people he came in contact with during a long and colourful life. Two elder brothers exerted two different kinds of influence – from Herombo Charan Chatterji, employed in a civil engineering job in distant Kakinada in what was then Madras Presidency, he imbibed a strong sense of duty toward family and friends; and from Shiti Kontho Chatterji, the first staff correspondent of Amrita Bazar Patrika in Dhaka (East Bengal), he learnt his first lessons in journalism which were to stand him in good stead in later life.

Born in the mosquito-infested village of Konokshar in Bikrampur (now in Bangladesh), father belonged to what he frequently described as an “honourable family of some education and little means”. The poverty he had to contend with in his boyhood and youth would have been far worse if the generous hand of his second brother Herombo Charan had not been lovingly extended to alleviate the family’s straitened circumstances. It was a habit with my father to tell people very close to him that “Gobindo Chandra Chatterji was my jonmodata (biological father), but it was Herombo Charan Chatterji who was my onnodata (hallowed provider)”. Couched in that clearly pronounced statement were, I think, two distinct emotions – heartfelt gratitude bordering on reverence for the much older brother, and a deep sense of disappointment verging on resentment for a father who could have been more responsible towards his progeny. To make things clearer, my grandfather belonged to a generation many of whose members lost no time in getting a second wife once the first died. They kept on having children without a thought as to what would be the latter’s fate in the absence of their begetter. This was exactly what happened to my father who was only four years of age when my grandfather passed on. From his first marriage my grandfather had several children, and from his second, as many as seven sons and a daughter. My father was the youngest of the eight and had an early life that he would have liked to forget but for the affection he got from Herombo Charan; “my saintly brother” was what my father called him.

For his “poor and luckless” mother, my father felt life-long sadness. She was an unlettered woman but knew the value of education. She was forever encouraging her youngest child to do his studies well “Porashuna bhalo koira koro, shob dukkho ghuichcha jaibo” (Do your studies seriously, everything will turn out well).On the verge of retirement from his Tisco job when father was able to build a modest house, he named it ‘Sarala Smriti’ after his mother who knew little or no happiness in her married life. To be able to commemorate his mother, however humbly, must have seemed a great achievement to my father.

Perhaps a few more words about Herombo Charan are necessary. Right till the day when my father graduated from Jagannath College (now Jagannath University) in Dhaka, he kept receiving financial and emotional support from his beloved Shona-dada. If it is true that the personal is political, and the more personal the more political, then the quality of helping out people in distress that my dear father showed all his life is to be greatly attributed to the example he had before him in the shape of the portly, smiling figure of his elder brother slaving away in distant Kakinada to provide not just for his large immediate family but for several of his younger brothers living precariously in the backwaters of East Bengal. As it often happens in such cases, our Shona-jetha did not have a long life; he was in his early fifties when he had pneumonia, and died. Also dead within months of his untimely death were three widows in the village of Konokshar; therein hangs a forlorn tale. These childless women had lost their husbands at a young age, whereupon they were turned out by their in-laws. Learning of the destitution in which they were spending their days, Herombo Charan took it upon himself to send them a little money every month to take care of their need of rice, salt and jaalaani (cooking fuel). They would go around the village telling people how their “son Herombo” never failed in his self-owned commitment to them. So, when Herombo Charan died, so did the three widows – all of starvation and in quick succession of each other.

*****

One could say that journalism was in my father’s blood. His father was a small-time lawyer with many mouths to feed. However, he made time to do some writing in the local Bengali papers. I am speaking of late 19th-century and early 20th-century Bikrampur in what is now Bangladesh – a region where education was highly valued and graduates were to be found in many homes. When Gobindo Chandra, my grandfather, died, my father was but a child. After years of struggle in his ancestral village, one day he found himself in Dhaka city to study science in Jagannath College which boasted of several luminaries on its faculty. It was while he was still a student in Dhaka, the second city of undivided Bengal renowned for its intellectual and cultural heritage, that he served as an apprentice to his third brother Shiti Kontho, who was then attached to the Calcutta English-language daily Amrita Bazar Patrika, which enjoyed great popularity among educated city people. Shiti Kontho, our Ranga-jetha, was a short, dark man inordinately fond of the British whose ways he was given to aping, sometimes with pathetic results. Possessed of a volatile temper that frequently visited both his helpless wife and my equally helpless father who was living under his roof in Dhaka, Ranga-jetha, however, had his good points as well. He was a thorough professional and a stickler for perfection in whatever he did. His favourite author was Charles Dickens whose novels he read and re-read with fanatical devotion. He dutifully passed on his love of reading as well as his adherence to principled journalism to his much younger brother, my father. I have a feeling that Dickens was their favourite because in their own financial inadequacy and in the materially deprived nature of their lives, they could easily identify with the great writer’s best-known characters, victims of poverty and class tyranny.

Be that as it may, if there was one thing not to be found in journalism in my uncle’s time in Dhaka or, later, in my father’s days in Jamshedpur, it was money. There was social prestige if someone was found to do his scribe’s job honestly and well, but remuneration worth mentioning was hard to come by. Even the best of newspapers or the well-known news agencies were miserly, sometimes in the extreme, when it came to paying their ‘staffers’, let alone the poor ‘stringers’, unprotected by law of any kind, yet expected to give of their best at all times. My father is best remembered by some people in Jamshedpur for the distinguished stint he served with PTI. Today’s young journalists are likely to be shocked or maybe amused to learn that a veteran like my father gave his heart out as Jamshedpur’s ‘PTI man’ for a princely sum of Rs.75/- a month! Then, what was it that made him practise his chosen vocation in the exemplary manner he did for so many long years? It could only have been for the love of it. How often did I hear him say, yes, there was no money in journalism, but there was prestige and finally the feeling of doing something useful for society which gives so much in so many ways to each of us all the time. Today’s smart young men and women seated before computers typing out their ‘copy’ may remain untouched by such sentiments, but truly there was a sense of mission in those early journalists which their counterparts of today would do well to learn from. But, are they prepared, are they willing, do they have it in them to give new positive twists to the profession when it is precariously situated at the crossroads?

Many an honest and fearless journalist has had to pay dearly at least once in his working life. My father’s role during the 1964 communal disturbances in Jamshedpur and the price he had to pay for it is a case in point. In those dark days when gangs of thugs were allowed by a callous administration to roam freely and hold the city to ransom, father, along with some others of similar disposition, went about asking people of both communities to eschew violence. Their efforts bore result, but father, who had on some earlier occasion incurred the wrath of the then Congress Chief Minister of Bihar, Krishna Ballabh Sahay, was put in jail on charges of having instigated hatred! He was detained in jail for one whole month without any charge being formally brought against him. K.B.Sahay was known for his vindictiveness towards those who refused to carry out his wishes. Perhaps, father would have been unlawfully kept in jail even longer if journalists of Bihar had not come out in full strength against the injustice done to him.

Writing in the valedictory issue of Motif, Amal Tribedi, a Purulia journalist, dwelt on the incident of father’s incarceration at some length. “Some journalists of West Bengal, too, made it an issue and brought pressure on the Bihar government to release Devi-da. Added to this were questions raised on the floor of the State Assemblies of Bihar and West Bengal. The matter even went up to the Lok Sabha. As a result of the combined pressure on the K.B.Sahay government, Satyendra Narayan Singh, Home Minister of Bihar, visited the Jamshedpur jail to meet Devi-da. Mr. Singh expressed his regrets and arranged for Devi-da’s release.”

Almost a decade after the communal carnage, this writer re-visited it in the shape of a poem which was carried in The Illustrated Weekly of India of the Times of India group by its then poetry editor, Nissim Ezekiel. Written in a simple style that one hoped would appeal to common readers, the poem sought to fuse the personal with the political. Every death diminishes its beholder, but there are some deaths that diminish more than others. On top of that, if the death is that of a friend, is any language sufficient to express the anguish in the soul of the one left behind?

Victims

I remember the night the murderers came:

fire and bigotry in their midnight eyes,

gnarled fingers caressing flashing blades.

Swiftly they set to work. Father,

smalltown journalist, incurable do-gooder,

committed to

“You may or may not be a poet

but a citizen you must be”

rings the police and fire brigade.

Two hours later the law arrives.

By then, the Ali’s – father and son –

are securely settled in Allah’s deathless realm.

Mounir, neatly halved,

lies frozen in his mother’s arms,

his father stabbed only sixteen times.

After a week father is arrested:

bloody communalist, suave author of death.

He takes it coolly, without protest,

simply turns to us and says,

“To suffer

you don’t always have to do wrong”

the meaning of which escaped me then.

Years later I realized

with brine-hot remorse

it was at that moment my childhood died.

Mounir Ahmed or his father, Mubarak Ali, were not the only victims of the carnage that visited Jamshedpur in the bedevilled summer of 1964. Mohit Choudhury was a Muslim, young, educated, well-employed and of a pleasant disposition. He was in love with and expected to marry Tripti Bhattacharjee, who had similar plans. But destiny intervened, the marriage never happened. Mohit was waylaid by a well-armed group of hoodlums and stabbed to death. Tripti never married, immersed herself in studies, collecting more than one degree. In course of time she started a college called the Institute of Labour Studies in Jamshedpur and remained its director till her death. My father was Devi-da to both; she was Tripti-pishi to us. Till his very end, whenever father came across a report in the papers about a communal disturbance, he would let out a silent sigh, presumably for the two bright young people who could not come together.

Vidyarthy Chatterjee writes on cinema,society, and politics.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER