36 years after the anti-Sikh pogroms, murders– immediate and subsequent– remain unsolved, unacknowledged, unreported.

This November marks 36 years since the anti-Sikh pogroms in India. Hearing the voices of survivors debunks the propaganda that this violence was spontaneous; or that it was instigated, condoned, and beneficial to only one political party; or that the violence was contained swiftly—survivor stories exemplify how the violence of 1984 started cycles of violence that played out across India.

One mother’s story here connects the violence in New Delhi in November 1984, to violence outside of New Delhi in 1984, to the deathly difficulty of Sikh relocation to other parts of India after 1984. Her struggle exemplifies persistence; resistance; political insight; and personal courage against state-sponsored gaslighting. Excerpts from the chapter “Guavas and Gaslighting” in the new book Faith, Gender, and Activism in the Punjab Conflict: The Wheatfields Still Whisper, illustrate how the blueprints created in the 80s-90s India are playing out in India 2020: demonize one minority community to distract attention from real national problems.

She had only temporarily left her heart in Bidar, Karnataka. Kuldip Kaur had encouraged her youngest child and only son, Ginnu, to move to South India, far from their comfortable South Delhi home. As he had graduated from the elite Modern School, Delhi, Kuldip Kaur wanted to spare her shy, young turbaned boy the violence against Sikhs in North India. A Sikh engineering school in Bidar, Karnataka, sounded like the perfect reprieve while things settled at home.

“They had managed to eject Sikhs from the mainstream. Sikh men were seen with suspicion everywhere around us, after 1984.” During the November 1984 pogroms, Kuldip Kaur’s family had eventually been forced to take refuge in a Hindu neighbors’ home.

“To get reelected, they had unleashed violence on Sikhs. And we began feeling unsafe right at home. My son, he had obtained admission in colleges in Delhi. But we travelled to Bidar Sahib. We paid respects at Nanak Jheera.”

***

The [cola truck] would come for the crates each month. Take away the dozen empty glass bottles for a full set of black, orange, and yellow colas. By November 1, 1984, scrambling to find weapons in their homes, some Sikh households collected these bottles from their kitchens and pantries to use against the marauders—these more fortunate, more wealthy Sikhs had some time to prepare for their defense. Crude Molotov cocktails against mass, armed mobs.

“They had first televised her bloodied body for a whole day, and then the next day, systematic killing began in earnest,” explains Kuldip Kaur of the events that would convince her to send her only son, Ginnu, as far away from Delhi as possible. Indira Gandhi had been assassinated on October 31, 1984. “Now no Sikh was safe,” Kuldip Kaur remembers, sitting in her home in the affluent south Delhi neighborhood.

After operations code-named Bluestar and Woodrose had seared through its countryside, Punjab would become eerily uneventful in November 1984, while an anti-Sikh pogrom unfolded everywhere outside the Sikh heartland, starting with New Delhi. “On three successive occasions in 1984 Sikhs as a people were attacked. On each of those three occasions, their social class, their family back- ground, their service to and positions in the structures of the state signified nothing. The fact that they were Sikh removed their status and their rights from them,” writes Joyce Pettigrew.

“First the assassination news that shocked everyone, and then the rumbles that some mob is marching,” recounts Kuldip Kaur. “People started advising each other: call everyone back home, from schools, from offices, from work sites. Because on television they reported she was killed by Sikhs.” In contra- vention of the usual practice of not revealing information that might incite communal violence, All India Radio had quickly noted that the Prime Minister had been gunned down by her Sikh bodyguards. “But nothing happened that day or night really,” remembers Kuldip Kaur.

Indira Gandhi’s dead body lay at the elite All India Institute of Medical Sciences. Her son Rajiv Gandhi had landed back in New Delhi hours after her death. The market near AIIMS had seen attacks and the first bonfire of Sikh turbans soon after Rajiv’s arrival. About half a dozen deaths were rumored. The chief executives of the ravenous violence that would follow now thronged around Rajiv Gandhi: “Significantly, about 1730 hours, when Rajiv Gandhi came out of AIIMS after seeing the dead body of his mother, he was greeted with the slogan Khoon ka badla khoon se, blood for blood. H.K.L. Bhagat, the doyen of Delhi’s underworld urged the crowd, ‘What is the point of assembling here.’ Their field of operations lay elsewhere.”

***

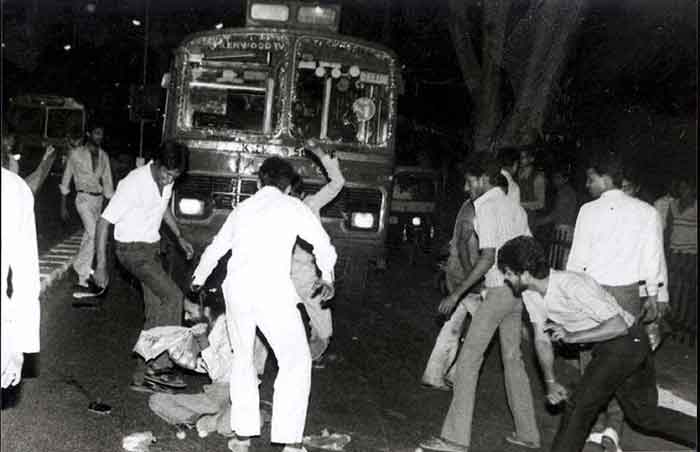

“And then, on November first, the mob started marching,” remembers Kuldip Kaur. “In our market, a posh market, a very famous market, the stores were largely Sikh-owned. They started with looting these shops. Woodlands. Bata. Taking away bagfulls of shoes. And electronics shops, television shops. Just pulled away whatever they wanted. And the Sardar men by now knew not to come out. So some of the women from these families in fact went out to see if they could save their businesses from the arson. And they went to the policemen, who just laughed at them, said, ‘Bachaa lo jo bachaana hai! Try saving what you can!’ They barely got back home safe.”

But homes were not safe either.

“The warnings would crescendo many times throughout the day: The mob is coming, the mob is coming! They hadn’t come on our road yet. But we had neighbors, very good friends, who said, ‘Please don’t stay at home. Come over to our house.’ First, my husband just wouldn’t even hear of the idea. ‘We are not going to hide,’ he said.”

“Then, in the adjoining locality, the mob entered a Sardar house. A big business family. And they desecrated everything, looted everything, rolled the carpets out, stole the silver, and then set fire to the house. And then they got into gurdwaras, and in one gurdwara we knew well, they rolled the local bhai saab in the floor rug and set him on fire. He was half burnt, half alive!”

The June attacks had removed forever any barrier in the Indian psyche to attacking faith centers. “Nothing was sacred anymore, everything was permitted,” wrote Ivan Fera in 1984, tracing the coordinated carnage and ritualistic killings. “It was the first time that such invasions into the psyche of a particular community were carried out for purely political ends. Officially violated to this extent, the Sikhs were now common fodder for everyone.”

“Not in our wildest dreams did we ever think anything like this could happen,” says Kuldip Kaur. “That we would have to scurry to our neighbor’s house. You know, we had a little doggy at that time. My neighbors were the ones who told me, ‘Bring him along too, otherwise when the goons break in, he will come looking for you and give you up!’ I realized they were picturing our possible fate. We stayed, curtains drawn, for a day and a half, holed in. Couldn’t get any supplies. Nothing.”

“And we were the fortunate ones. Across Yamuna, in poor colonies, they brutalized people. Sikhs were tortured to death, slowly, deliberately. Their bodies desecrated.”

***

“The killers had no fear of police or the authorities in satiating their blood lust, calculatedly planned by senior Congress politicians armed with voter lists,” writes eyewitness journalist Rahul Bedi. The foot soldiers were the Jaats, the Gujjars (herders, often relegated to slums in urban areas), and the impoverished Dalits. The Haryana Chief Minister Bhajan Lal had further propelled the murderous storm: droves of Haryana policemen in plain clothes are said to have been bused to Delhi, joined by local strongmen and criminals, aided by the Delhi police. Some poor people, formerly used by Congress strongmen to fill buses to political rallies and protests—a common practice by political parties then and now—used this opportunity to profit, and many to exhibit power over the new national enemy. Rickshaw pullers, drivers, gardeners, maids, mailmen, had temporarily overcome their oppressed status in society and held sudden power to loot, rape, pillage, kill. Those orchestrating the crimes kept their hands milky clean, greeting world leaders for a somber state funeral.

Indira Gandhi’s state funeral had been delayed three nights until November 3. “Only after her funeral things settled down,” Kuldip Kaur remembers. “Even then, the trains, the buses, any sardars coming, going, they were snatched out, hacked to death.”

**

Seven thousand to twenty thousand Sikhs were killed across India; at least 3000 perished in New Delhi alone.

**

Kuldip Kaur says, “I believe this was all about the coming elections. In fact, some people say that even if Indira had not been killed, this would have happened. That she was on the lookout for an excuse to unleash violence on Sikhs, with which the Hindu and Muslim vote bank could be secured. Because, child,” she says in a sweet voice belying no regret at this arithmetic fact, “Sikhs are just very few in number. We are just two percent of India’s population.”

Many remain convinced that the lull of October 31st could hardly have been enough time for the meticulous organizing that wreaked havoc on tens of thousands of this minority community across the country.

“The assassination of Indira Gandhi on the morning of October 31, 1984, pre-empted Indira’s Operation Shanti, to commit mass scale genocide of the Sikhs all over India, by over a week,” writes Dr. Sangat Singh, a retired civil servant, and former officer in the Ministry of External Affairs, India. He says Gandhi’s next political move to solidify her voter base was slated for “around November 8, when the Sikhs would assemble in various Gurdwaras for Guru Nanak’s birthday celebrations. According to the plan, large-scale skirmishes virtually amounting to a war, were to take place all along the India-Pakistan borders. And, it was to be given out that the Sikhs had risen in revolt in Punjab and joined hands with Pakistani armed forces.”

“She had a plan,” says Kuldip Kaur. “But given Bluestar, given Woodrose in the countryside, the anger in Sikhs was high and contagious. Her own bodyguard was provoked. And assassinated her. And so this then gave the government their desired chance!”

***

There is believed to be something special in the soil of Bidar. Masons taste test it before using it to create the black oxidized metal handicrafts, with intricate inlay work, that have brought Bidar repute since the fourteenth century. Bidar was the first independent Muslim kingdom in medieval South India. In the early 1500s, during his travels southward toward Ceylon, Guru Nanak stopped there. The jheera, spring near the gurdwara in Bidar, remained sweet-tasting and brought fame and followers to the Nanak Jheera. Then, three centuries later, in 1699, when Guru Gobind gathered Sikhs and initiated the order of the Khalsa through five beloved ones, one of them, Sahib Singh, was from Bidar. Six miles from Bidar’s jheera, the legendary Sikh woman warrior-leader, Mai Bhago, is believed to have visited to spread the Sikh ethos, as instructed by Guru Gobind himself.

“During our visit,” says Kuldip Kaur, “we decided we will enroll our son in the Sikh-run engineering college there. I told myself that he’ll be safe in Guru ki nagri,” Guru’s own townlette.

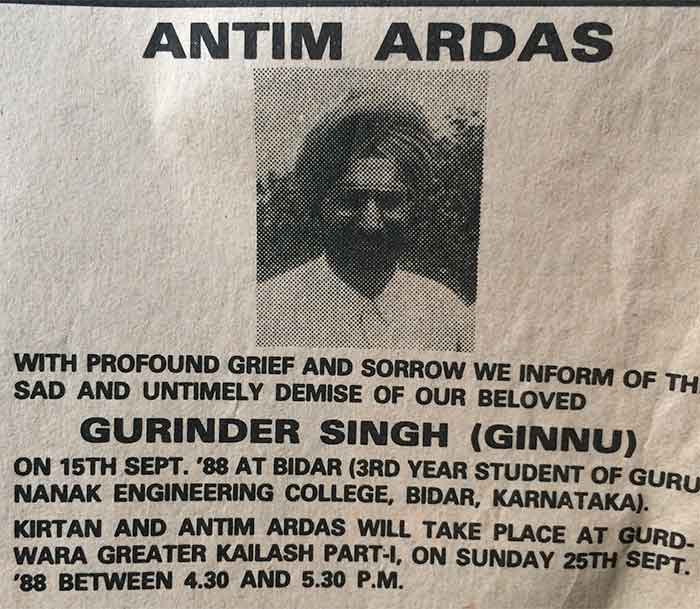

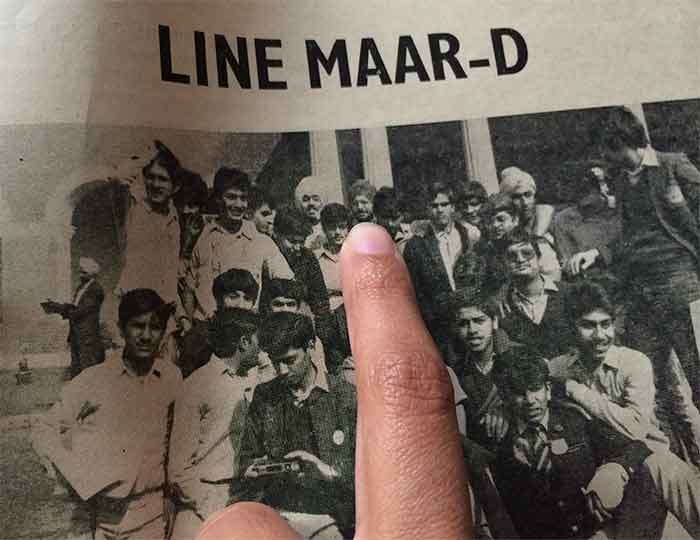

So Gurinder Singh, Ginnu, moved to Guru Nanak Dev Engineering College, Bidar. In September 1988, just short of 22, he was in his fourth year, when things changed forever.

“Shiv Sena had caused disturbances there even in 1987.” [Shiv Sena is a right-wing regional political group, espousing Hindutva ideology, founded in the 1960s in Bombay, Maharashtra] Kuldip Kaur recounts the buildup as she understands it in retrospect. “Joga Singh was the owner and he had expanded to build a medical college, pharmaceutical college, nursing college, besides the engineering college. The Shiv Sena felt Sikhs were gaining too much influence, it is said. We didn’t know what was going on at the time. Later we learnt about these dynamics. And what did the local government do? They removed from duty any influential Sikh officers. There was a Sikh left in charge at the airport, but others had been transferred by 1988.”

Kuldip Kaur traveled south in mid-September 1988.

“I had gone to Hyderabad. And I had bought tickets for September 17, for both of us to return to Delhi. On the thirteenth, Ginnu called me from Bidar to confirm. And then he said, ‘I’ll call you day after.’ I kept waiting on the fifteenth, but no phone call came. I began wondering. And then I tried contacting people in Bidar. And I found someone who knew that Sikh in charge at the airport. They got back to me and said there were some riots. That was the first we heard of anything happening, nothing had come in the news or anything. Nothing had come from the school. I got frantic, I pleaded, Please find out about a Gurinder Singh.”

The media silence on Bidar would run into weeks.

“And then my source got word and said the children are all in the gurdwara, they are safe.”

“See, Nanak Jheera was high up on a hill. They were supposed to be all gathered there.”

“I called again, asking Ginnu be put on the line. They said, ‘He’s okay, but not around.’ Those days, there were no mobiles and all. And he was not living in the hostel. As a senior, he was in a rented house with some other boys.”

“I stayed up that night, consumed by dread.”

“Next morning, I heard a handful of students had been killed. That’s when we left for Bidar.”

“In their rented home, I saw everything had been ransacked. Books strewn all around. And no boys. When we asked around, we learnt that a mob had come, had chased them. There was now no sign of these four boys.”

“These boys hadn’t known, but people said the houses where Sikhs were living had been marked before. … We slowly learnt six boys were definitely dead. My son, it was clear now, was one of those. We knew two of the others were brothers, one was Ginnu’s classmate, the other was in first year, he had just been admitted in July. Bodies had been thrown down a well. The well was seven or eight kilometers from where they were murdered. The rampaging mob wouldn’t have carried them. We heard the police picked up the bodies, put them in a jeep, and threw them.”

“We went the next morning, to retrieve their bodies. All swollen. All. Just from his clothes. Recognized.” She pieces her gasps together. The body had severely decomposed between September 15 and 18 in a well just about a 100 meters from the Superintendent of Police’s residence.

“By then, my husband had arrived. We conducted the cremation, and then left. We returned to Delhi, but nothing ever returned to the same. Our house, many houses, were plunged into darkness.”

As the Sikh students’ families—many educated, all of relative economic privilege, all devastated—slowly began returning home, media reports finally started emerging.

“The general silence was so egregious, we decided a PHRO [Punjab Human Rights Organization] team must go down there to investigate,” says Justice Bains [retired Punjab & Haryana High Court Judge; PHRO founder and human rights activist]. “I went along with Gurtej Singh, who had served in the South during his IAS tenure and was familiar with the region.”

The team arrived in Bidar exactly a fortnight after the violence. Their vehicle, driver, luggage, persons were diligently searched by policemen who stopped them at the city limits. “Now, all this police had kicked into action, while then, for three days, as butchery took place, policemen either looked away or cooperated,” says Bains.

**

The Chief Minister of Karnataka, Mr. S.R. Bommai, recalcitrantly made statements regarding the violence only after much outside attention, and even then only bolstered rumors besmirching the character of Sikh victims in Bidar.

Bidar has not been written about since these early reports. Sikhs, especially outside Punjab, largely learnt to remain silent: bringing attention to their second-class status was fraught with danger; the persecuted community was the easily identifiable “national enemy.”

The post-1984 fear had quickly morphed Sikhs’ sense of their own reality: first outside Punjab, later inside as well, the Sikh community was effectively “gaslighted.” Like an abuser often succeeds in making a victim of domestic violence question her own sanity, memories, values, and truths, this community lost confidence in its own beliefs and experience. Sikhs increasingly found alternative explanations that did not implicate the abusers. For example, the Bidar carnage was rationalized by some as a result of Sikh boys teasing local girls and provoking the local boys—even as the PHRO determined that all available evidence pointed to no actual incident or complaint of such transgression: “In any case, even if some incidents of gross misbehavior of the Sikh students is shown, that would neither explain the organised and determined character of the incidents nor would it justify in any way whatsoever the orgy of loot, arson, and killings.”

For Kuldip Kaur, who had retrieved her last born’s unrecognizable body with her own hands, the reality of the depravity remained crystal clear. “Wasn’t very much we could do. Kept living as best we could, recalling, Teraa [kiyaa] meetha laage.” Your will is our sweet command, said the [fifth] Guru.

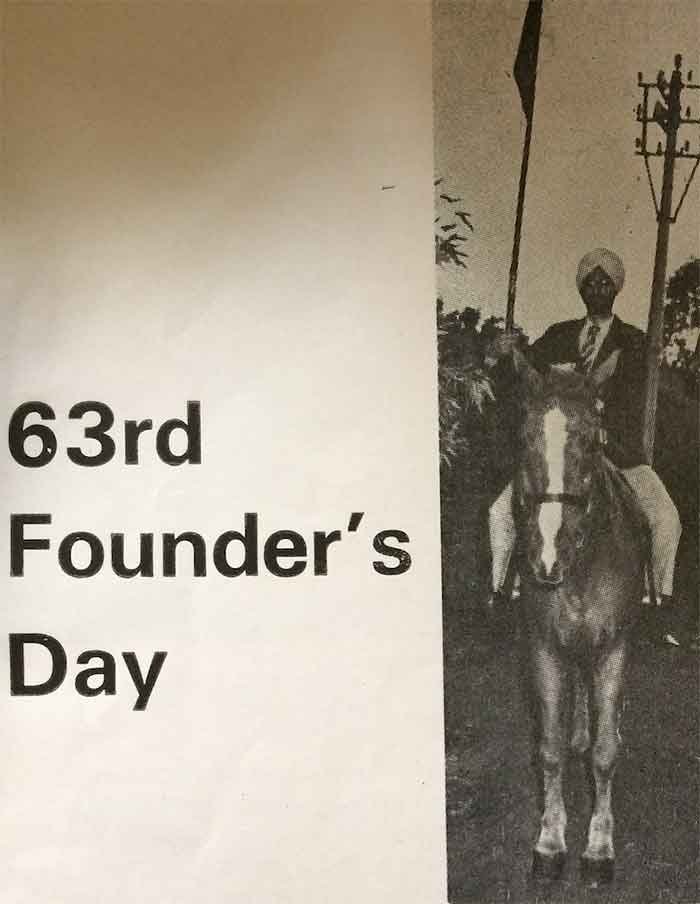

Ginnu’s sister says, “He was such a calm and quiet child, the baby of the family.” She lovingly shows me his yearbook and reports from Modern School, Delhi. A history buff, theater society enthusiast, avid equestrian.

**

“There was a very clear message that we shouldn’t talk about the murders,” says Kuldip Kaur. The Bidar school had quickly been reopened and continued business as usual. One month after the violence, the Principal had sent a stiff form letter commiserating over the family’s loss, with no comment on the injustice of the killing. Incensed, Ginnu’s father, Mohinder Singh, wrote a letter noting how this Principal and Joga Singh, the owner of the educational conglomerate, neither met with any of the bereft parents nor attended the painful last rites. Despite being clearly warned of the impending doom—Joga Singh had even fled with his family for safety—the school administration took no preventive or corrective measures and now shirked their duty again. “All those killed were my sons and all those suffering are also my sons. If you really want your soul not to torment you, you should yourself resign the post and work for the welfare of the remaining students and serve the future youth of the nation for the rest of your life.”

Ginnu’s mother, Kuldip Kaur, remembers, “After his bhog, we thought, Okay, let’s ensure remembrance, and then put out a notice in the newspapers that six children were shaheed in the riots. Didn’t let us use the words ‘riots’ or ‘shaheed.’ So finally we put out the announcement that ‘We lost six precious lives in the madness of this world.’”

The family continues its frustrated attempts at counter-memory and, on every anniversary of the Bidar massacre, they continue to print the newspaper remembrance notices. Ginnu’s father started a trust in his name and wanted to open an eye hospital in his memory: he always remembered cremating decomposing Ginnu’s body without his eyes, which had always blinked behind studious glasses.

Eventually, Bidar’s unacknowledged trauma resulted in another execution. Ginnu’s sister says, “A Sikh student, still reeling from what he had seen, killed owner Joga Singh, holding him responsible for not protecting the boys against the mobs. The student surrendered and received capital punishment.”

“Our lives of course were ruined,” says Kuldip Kaur. “But the entire environment in India also only spiraled down.”

***

Mallika Kaur is a lawyer and author of “Faith, Gender, and Activism in the Punjab Conflict: The Wheat Fields Still Whisper,” Palgrave MacMillan (2019). She teaches at UC Berkeley School of Law.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER