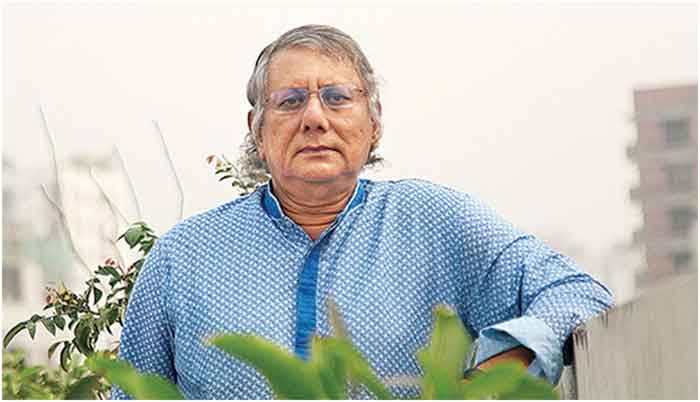

My interview with the celebrated filmmaker centers on his recently released film “Rupsa Nodir Banke” (Quiet flows the River Rupsa). 2017 Ekushey Padak (the second highest civilian award given to a citizen of Bangladesh) winner Tanvir Mokammel needs no glowing introduction. He is a well-known filmmaker, director and published author of our time. He won Bangladesh National Film Awards a total ten times for the films Nodir Naam Modhumoti (1995), Chitra Nodir Pare (1999) and Lalsalu (2001).[5] He is the current director of Bangladesh Film Institute in Dhaka (Wikipedia). Mokammel was born to AFM Mokammel and Begum Sayida Mokammel. His parents were highly educated and progressive-minded. His father was a Magistrate, and mother was a college Professor during the British Raj. They lived in Kolkata’s Park Circus area before the partition. Mokammel was raised in his family home in Khulna town (an industrial city located in southern part of Bangladesh.) In an interview, he once defined his parents as: “unusually modern and cultured persons” for their time. Tanvir got his higher secondary and university education in Dhaka. While a student at Dhaka University’s English department, he became involved in left-wing student politics. In his youth, he also worked as a journalist in “Ekota,” a weekly newspaper for the Communist Party. He had a gift for filmmaking, and along with some friends formed a film society and named it “Dhaka University Cine Circle.” Mokammel’s mother early on recognized her son’s sensitive and creative side. With her blessings and gift of ten thousand takas, Tanvir started his film career. From then on there was no looking back for him. His work and creative pursuits spread across all genres of creative forms. Mokammel writes his own stories, screenplays and seldom directs films by other writers. At a time when film industry in Bangladesh is working in diminished capacity with outdated stories, Mokammel’s films stand out as “Art for art’s sake.” His reputation as a highly talented documentary and feature film maker has crossed borders, race, and religion. He has thus far made fifteen documentaries and seven feature films; “Rupsa Nodir Banke” is his seventh feature film. He is unfazed by all the recognition, and quite nonchalant about getting all the notable awards that are truly deserving of him. With an aura of mysteriousness and great vision, Tanvir Mokammel creates art through his films. He is devoted to making meaningful stories about our land; he is a voice for the voiceless. One of his earliest documentaries, “Bastrabalikara” is about the plight of female garment workers suffering in silence to earn a living for their families. Mokammel is one of the pioneers of such documentaries since the liberation of Bangladesh. Through his films and documentaries, we came to know about many untold stories of injustice, prejudice, sacrifice and the suffering of our fellow citizens. After watching any one of his films, I come away with the feeling that he wants to create a society where people are free and perceive human dignity as their inherent rights. Mokammel is currently busy filming a biopic on Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman titled “Madhumati Parer Manushti.” In his own words why he makes films: “When I was young I would get excited about receiving awards. But, to be honest, these days, I feel least bothered about awards. I have even stopped submitting my films to any competitive festivals. I do not want to be part of any rat race any more. I know no award will help my films to remain viable. My films will survive only if I can create true art. So, my film unit and I try earnestly to create some meaningful art on the screen. The rest is unnecessary for me. I am a firm believer of what Lord Krishna had told Arjun during the Kurukhetra battle: Do your duty and don’t bother for the results, because, that is not for you to enjoy.” (New Age)

This interview was conducted online.

Welcome Tanvir Mokammel. A much-awaited release of the film “Rupsa Nodir Banke” (Quiet Flows the River Rupsha) written and directed by you coincided with Bangladesh’s Bijoy Dibos (Victory Day). As its creator and director, how do you feel about the release of your new feature film?

The film “Rupsa Nodir Banke” was completed way back in February of this year. Then the Covid-19 Pandemic struck. We simply had to sit on with the film for almost ten months. Then we decided, come what may, we would release the film during Bangladesh victory week, that is, in mid-December. I am happy we could do that accordingly. The film had its premiere on 10th December, and from 11th December the film is being shown at Shahbag’s Public Library Auditorium, Star Cineplexes and other outlets. Now we are preparing to release the film online. I am very relieved, and thrilled as well, as the film “Rupsa Nodir Banke”, two years of our labour of love, has been finally released.

In this historical film, through the portrayal of Manobratan Mukhupadhay, the protagonist, you bring alive the character of a real life leftist leader Bishnu Chatterjee of Khulna. The story centers on his life’s journey. Why was Bishnu’s story particularly important to depict him as the lead character in your film? To make the main character and the supporting characters develop, how much fiction was added?

Not much fiction actually. The anti-British Swadeshi movement, the construction of a dam by thousands of peasants, the famine of 1943, the riots of 1946, the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the language movement of 1952, the United Front election in 1954 and finally the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, all were real historical events which the film tried to depict faithfully.

The main protagonist of the film Comrade Manob Mukherjee was modelled, to some extent, on the life of Comrade Bishnu Chatterjee from Khulna. However, there were others as well. Comrade Mohammed Farhad, the general Secretary of the Communist Party of Bangladesh once told me that there were one hundred and thirty-six such dedicated leftist leaders all over Bangladesh who had been in exile in the Andamans and in different other jails. Sometimes they had been in prison for ten, fifteen, twenty years. The story of the film has taken the experiences of mainly four such veteran comrades. Of course comrade Bishnu Chatterjee’s life figured in most prominently in the film, but snippets from the life experiences of Comrade Jiten Ghosh of Bikrampur region, Comrade Gyan Chakravarty from Dhaka and Comrade Ratan Sen, another veteran peasant leader from Khulna, were also incorporated in the storyline of the film.

The film covers important and progressive historic movements. Instead of capturing how the Razakars (war criminals) killed elderly Manob Mukherjee during the 1971 Liberation War, why did you feel it to be essential to focus on other movements as well to pursue the main goal of the film?

Comrade Manob Mukherjee was a political activist. Political movements were very much part of his existence. Besides, our intention was to show the character in our historical perspective. So all the important events and movements of this land during the last few decades, like anti-British Swadeshi movement, the famine of 1943, the riots of 1946, the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the language movement of 1952, and finally the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971, all figured in. We tried to portray the character of Comrade Manob Mukherjee on the backdrop of those major political events and movements of our history in which he was an active participant. To me he was like a Greek tragic character. He had all the great qualities, fought bravely against all the odds, but destiny, here in the form of time, was not in his favor. A real tragic character indeed!

At a time when COVID-19 is raging all across Bangladesh, the showing of the film now clearly poses safety challenges. I had read that the film is being shown at Public Library Auditorium in Dhaka thrice every day. It is also being shown in some Cineplex’s. Are you worried that there may not be a huge audience turnout? Can people really maintain social distancing in a movie theatre?

The Covid-19 is a matter of grave concern. But at the same time the reality has dawned on our people that they have to live with the Pandemic. There simply is no way out. Bangladesh, though being badly affected by Covid-19, has not declared any locked down. Life, in a limited way, is going on. Cinema halls and theatres are open. We had been sitting with the film for long ten months. Moreover, as December is the month of our victory, the liberation of the country, and as our film has also something to do with the liberation war of Bangladesh, we thought it would be the appropriate time to release the film. We knew that due to the Pandemic the turn out in the cineplexes, even in the Public Library Auditorium, where we normally get a satisfactory audience, would be rather low this time. But we had to bear it anyway. During the film shows, we try to remain very careful about the social distancing as well as the health rules prescribed by the government.

But as social gathering is still problematic due to the Pandemic, so we have decided to release the film online as well. From 25th December one may watch the film online.

As far as I know, you do not make movies for commercial success. As an “alternative” filmmaker, your aim is always to promote social change. Since this film was partially funded by the government, why not show it on government sponsored television channels to reach a bigger audience? Though it is not a telefilm, wouldn’t that enable millions who are locked inside their homes to view the film without going to a cinema hall?

The plan of showing the film in TV channels, not only government owned ones, but also in the private channels, and there are quite a few now in Bangladesh, is definitely on the agenda. We sure will do that but after some months. Besides, we are also planning to show the film online so that people can watch the film sitting at home. As the proverb says if the mountain does not go to Mohammad, Mohammad will go to the mountain, If people, due to the Pandemic, do not venture out of their homes to watch our film, we will bring the film to their homes. It will start from 25th December.

Through the powerful voices and sacrifices of your movie characters, you deliver a positive message. What is the central message the protagonist gives that is relatable in the context of today’s society?

I guess quite a few.

First, our Bengali identity. The Pakistanis tried to confuse our national identity. If became easier that way for them then to rule and exploit. The Liberation War of 1971 brought the Bengalee Muslims back to their root, that is, this very riverine delta of Bengal is our motherland, not the sandy Arab Peninsula. If you remember the last scene of my liberation war movie “Nodir Nam Modhumoti” [The River Named Modhumoti], after killing his Razakar uncle, the young Bengalee guerilla Bachchu ran towards the Modhumoti river and bends towards the river to drink water, and then in the soundtrack, the theme song of the film gets played “This Padma, this Meghna, this Jamuna/ This is my country/ This is my love.” So I guess, patriotism against extra-terrestrial Pan-Islamism is definitely a message. Manob fought for our Bengalee identity. Besides, social justice is another issue for which Manob fought all through his life.

Another poignant message from the film “Rupsa Nodir Banke” and the central character of the film Manob Mukherjee is secularism. In my other films like “Chitra Nodir Pare” [Quiet Flows the River Chitra] or “Jibondhuli” [The Drummer], even “Lalon”, all had this message of non- communalism, the desire for a secular society and polity in Bangladesh. You can say, as an Auteur filmmaker, a secular Bengali culture is the central message in most of my films. In addition, the film “Rupsa Nodir Banke” and Manob Mukherjee the main protagonist of the film, remain exponents of that idea too.

In January, “Rupsa Nodir Banke” is going to be screened at the 51stInternational Film Festival in Goa, India. It will be shown at the World Panorama Section of the film festival with the works of other exceptional and noted directors. Given the COVID-19 situation, what are your expectations? As of this writing “The state of Goa, has had 29, 343 coronavirus cases so far, with 368 deaths.” Is a realistic idea to hold a movie festival now? Are you concerned about the timing of the festival?

The Pandemic is definitely a concern. It is still a few weeks away. But I reckon January may not a suitable time to stage a film festival, given the figures you have quoted regarding the Coronavirus victims in Goa. But things have to move on. You remember the Beatle’s song during our youth “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da/ Life goes on”. Pandemic or not, life has to go on. I look at life and the events around me with that spirit now.

It had been widely reported that you made this film keeping the younger generation in mind to some extent. Therefore, you created a historic timeline that stretches from the Swadeshi Movement (of our land) to the 1971 Liberation War. Could you elaborate how you think this film might inspire them?

The present generation, not only in Bangladesh, but also all over the world, lacks interest in history. It is a global phenomenon. This is truer for the Bangladeshi youth where the ruling elites make a constant effort to distort our history, to make people, especially the new generation, oblivious about our glorious past. Therefore, it is imperative to keep history alive. Milon Kundera, the Czech novelist once said, “The struggle of people against power is the struggle of memories against forgetting”. The rulers want people to forget their past as it helps them to rule and exploit more ruthlessly. But people cherish those memories and it is the duty of us artists to keep those memories alive. Hence, I like to make films with historical content and place my character on the backdrop of some historical events. For the film “Quiet Flows the River Rupsa” the historical backdrop was rather on a big canvas, from the Swadeshi Movement of the 1930s up to the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. I believe it is very important for the youth of a country to know the history of his or her land. I guess, the “Quiet Flows the River Rupsa” will serve that purpose to some extent.

The fictional Manob Mukherjee had left his mark through his personal sacrifices. Can we hope he will have a positive impact on today’s youth? Is the new generation up for the task to use Mukherjee as a role model to bring forth momentous changes?

Bangladesh lacks good role models in politics, especially in the recent times. Political idealism, or an idealist man fighting for a just cause, is very rare in contemporary Bangladesh. Hence I wanted to tell the story of Comrade Manob Mukherjee and through him present a character to our youth to show that a man like Comrade Manob lived and worked in this very land and not so long ago too.

From the onset of 1905, the Swadeshi Movement became an emblem of nationalist beliefs in India. How much of this movement was highlighted in the movie?

Quite a bit, I suppose. The very political consciousness that the protagonist of the film Manob Mukherjee acquired was from the Swadeshi Movement. The phase of his shift from a young nationalist to a Marxist internationalist during his youth was shown in the first phase of the film. Reference of Chittraranjon Das and the anti-British struggle of that time also figured in the film. The theme song of the film “Ekbar biday de ma ghure asi” [Bid me adieu mother once] was a song the Swedeshis used to sing. So I reckon the presence of the Swedeshi Movement is quiet present in the visuals and in the soundtrack of the film.

The leftist leaders had continued with their movement until self-rule was established in the Sub-continent. They went through immense struggles and sacrifices (a lot of them were assaulted, arrested and shipped out to the Andaman Islands). With the Swadeshi Movement, India’s industrial sector boomed. Nevertheless, after the Partition the leftist leaders were rather pushed into the background. It happened when Bangladesh became a free nation as well. In your view, why do you think the leftist ideology is seen as a threat in the Sub-continent?

It is a class phenomenon. After the independence of India, and for that matter Bangladesh as well, the workers-peasants did not come to power. Power came into the hands of the national bourgeoisies and to the middle class leaders. They were not in a position, nor had the mental set up, to share power with the leftists, though they both officially and unofficially, would often pay homage to the sacrifices of the left leaders and activists for the liberation of the country. The leftists also had their share of mistakes. Like the ultra-left Randive line after 1947, which the communist Parties of the Sub-continent followed, had alienated them from the masses. They became isolated and marginalised. Later, the Communist Party of India (CPI) or the Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB) regained some ground but it took quite a while, or was never enough to become relevant in the mainstream power politics of the country.

Under colonialism, everyone had faced oppression. Why did the leftist leaders think the effect of colonialism on them was unlike others? Was it because their notions of freedom were entirely different from the others?

They definitely were. The leftists wanted to form Workers-Peasant’s states, at least the hegemony of the working classes. But the national liberation leaders of most of the newly independent countries, emancipated from the shackles of colonialism, were mainly the aspiring national bourgeoisie, or at best, from the middle class. So there was very little chance that the leftists would be happy with the independence as the workers and peasants again became victims. This time instead of the foreign colonial rulers, by the ruling classes of their own country. So conflict was inevitable.

Another reason was the Cold War situation of those decades of the 1950s, 60s, and 70’s. For the ex-colonial Western powers, the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc were their main enemy. So the leftists of the colonies, sympathetic to the Soviet Union, or often supported by the Soviet led socialist bloc, were considered enemies by the colonial powers. So the colonialists treated the leftists in their colonies very harshly, often ruthlessly.

You had directed “Chitra Nodir Pare” and “Nodir Naam Modhumoti” where the flow of the river was used as a narrative. In your films, as a metaphor, a river symbolizes the end of life or a great flow of life? Was the illustration of a river used as a path for the hero to take a journey? Or it was used to capture the minds of the viewers as it is a powerful component of nature?

Besides those two films you mentioned, quite a few of my other films including the new one “Rupsa Nodir Banke” and some documentaries like “Oie Jamuna” [Tale of the Jamuna River] or “Karnaphulir Kanna” [Teardrops of Karnaphuli] are named after some river. This naming of a film mostly takes place in my sub-conscious. A river indicates a place, a people of a region. Actually, we are a riverine country. In Bangladesh after every five or ten kilometres you will come across a river. So rivers exist very much in our consciousness and subconsciousness too. The rivers are in our gene.

Besides, the rivers of Bangladesh are beautiful. A river has one variety of beauty in morning, another kind in afternoon. And sometimes the beauty can be stunning. Therefore, any Bengalee visual artist, a painter, a photographer or a filmmaker, is bound to be attracted to portray the rivers in his/her work. I am just one of those Bengalee artists. I perhaps get more attracted towards rivers as you may notice from the fact that I have no house, no piece of land of my own but I have a boat. I often spend my time on my boat in the rivers.

And another aspect, which you tried to hint may perhaps, has something to do with it. That is the existentialist or the philosophical aspect of a river. Whatever happens on its both banks, a river keeps on flowing. An artist’s life is also a bit like a river. Whatever happens around he has to move on.

Is river a multifaceted element that triggers your creativity?

Yes, it definitely does. I am positive about it. When I am close to a river, I never run out of ideas. All kinds of creative urges come.

To chronicle Manob Mukherjee’s life journey why Rupsa River inspired you over any other?

One reason is spatial. The name of a river suggests an area, a people living in a region beside a river. The name Rupsa River in the film suggests that the events in the film mostly happened in that region near the Rupsa River. Comrade Bishnu Chatterjee of Khulna, whose life story was mostly followed to portray comrade Manob Mukherjee’s life, lived on the other side of the Rupsa River and would often cross the Rupsa to his area of action, which was in Dumuria and Baitaghata region south of Khulna.

The patriotic song “Ekbar biday de Ma Ghure asi” was composed in honor of Khudiram Bose as a farewell to his mother before he was sent to the gallows by the British. Was this particular song chosen to carry an overall message in the film?

That was the intention. The song “Ekbar biday de Ma Ghure asi” is a song used to be sung during the anti-British Swedeshi Movement. The song associates with a time, a period, a movement. The song is still very popular as a patriotic song. So wherever there is a struggle, a reference of sacrifice for one’s motherland, the song is sung. The main protagonist of our film Manob Mukherjee began his political activism during the anti-British Swedeshi Movement and was killed by the Razakars in 1971 during the patriotic liberation war of Bangladesh. During his school days, in a function, Manob also sang this song as a young boy. So we decided to use the song as a kind of a theme song for the film. The lyrics of the song were well suited to the theme and the visuals of the film and could be easily associated with the main protagonist of the film Comrade Manob Mukherjee’s life and sacrifices.

Zeenat Khan is a freelance writer and columnist. She writes short stories and nonfiction. Her multiple stories and nonfiction pieces have been published in an anthology, special supplements in New Age, the Literary page of the Star literature, and weekend magazines. A nonfiction essay was recently published in Kitaab International. Currently, she is in the final stages of editing her short stories to get the collection published by 2022. Since 2019, she has become a regular contributor to the countercurrents.org. She considers herself a social justice seeker and her columns usually focus on how to combat racial and social injustice. She covers many other topics including how to defend human rights issues, gender equality, current social problems, concerns relating to South Asia and beyond. She lives in Maryland suburbs, outside of Washington, DC with her physicist husband.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER