Americans’ trust in the federal government in handling major problems has fallen nearly to all-time lows, finds Gallup.

Based on an annual poll conducted between August 31 and September 31, 2020, Gallup found:

About 48% of Americans say they have a “great deal” or a “fair amount” of confidence in the government to handle international problems and 41% on its ability to handle domestic problems.

A “Trust in Federal Government’s Competence Remains Low” report by Lydia Saad said on September 29, 2020:

Americans want the government to take a more active role in solving the country’s problems, Americans’ levels of trust in the federal government to handle the two broad types of challenges the country faces remain near their all-time lows. Just under half (48%) say they have a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence in the government to handle international problems, and 41% say the same about domestic problems.

The latest figures, from Gallup’s Aug. 31-Sept. 13 annual Governance poll, are essentially unchanged from 2019 and match the averages recorded since President Donald Trump took office in 2017. They are also within one percentage point of the trust levels measured during former President Barack Obama’s second term, from 2013 to 2016, but below those in his first term.

In 2012, after Obama had declared an end to the war in Iraq and was promising to end the war in Afghanistan, Americans were particularly confident in the government’s ability to handle international problems (66%).

Gallup first asked these questions in the 1970s and then picked them up again in 1997, and has since asked them every year except for 1999. The trend since 1997 shows that trust peaked in October 2001, a month after 9/11, at 83% for international problems and 77% for the domestic arena. Since then, these figures have gradually trended downward and have mostly been at or below 50% since 2013.

Americans’ relatively low trust in the government to handle international and domestic problems is reflected in their ratings of the two branches of government responsible for foreign and domestic policy — the executive and legislative.

Currently, 43% of Americans say they have a great deal or fair amount of confidence in the executive branch, similar to Trump’s 42% job approval rating in the same survey. Confidence in the executive branch has been as low during the Trump presidency as it was toward the end of George W. Bush’s presidency (42% in 2008 and 43% in 2007).

At 33%, Americans’ trust in the legislative branch is on the low side for that trend — although not as low as in 2014, when it sank to 28% at a time of extreme partisan gridlock in Congress.

Meanwhile, trust in the judicial branch has remained relatively high across the past quarter century, with 67% currently expressing a great deal or fair amount of trust in it. This exceeds the Supreme Court’s approval rating of 53% in the same poll.

Local Is Best When It Comes to Governing

Gallup has measured trust in several other aspects of American government and public life since 1972. This includes trust in state government, local government, the mass media, the men and women who serve in politics, and the American people as a whole when it comes to making judgments under our democratic system about the issues facing our country.

Local government currently edges out the judicial branch in generating the most trust, with 71% of Americans saying they trust it a great deal or fair amount. Solid majorities also trust state government and the American people, while less than half trust the mass media and the people who run for or serve in public office. However, the current level of trust in the American people (56%) is tied for the record low, previously recorded in 2016.

Since 1972, majorities have consistently expressed trust in local government, state government, the judicial branch and the American people.

Trust has varied for the others, from about seven or eight in 10 viewing each positively at its highest point to as few as 28% at its lowest. Current trust levels in public candidates and officials, the executive branch and the legislative branch are near their all-time lows.

Americans’ Trust in Aspects of Government — Today vs. Historical Highs and Lows % A great deal/fair amount

| 2020 | High | Low | 2020 vs. Low | ||

| % | % | % | pct. pts. | ||

| Local government | 71 | 77 | 63 | +8 | |

| Judicial branch | 67 | 80 | 53 | +14 | |

| State government | 60 | 80 | 51 | +9 | |

| American people | 56 | 86 | 56 | 0 | |

| Men and women in political life | 45 | 68 | 42 | +3 | |

| Executive branch | 43 | 73 | 40 | +3 | |

| Mass media | 40 | 72 | 32 | +8 | |

| Legislative branch | 33 | 71 | 28 | +5 | |

| “High” and “Low” figures are from 1997 to 2019 | |||||

| Gallup | |||||

Partisans’ Trust Varies Greatly

As expected, Americans’ current rating of the executive branch reflects an enormous partisan gap, with 91% of Republicans versus 37% of independents and 6% of Democrats feeling confident in it.

The mass media — sometimes known as the Fourth Estate for its notable political and social influence — is the only other entity measured that rivals the executive branch in provoking different partisan reactions. Democrats (73%) are 63 points more likely than Republicans (10%) to express confidence in it.

The judicial branch, led by the Supreme Court, currently sparks a 24-point partisan gap, with 82% of Republicans and 58% of Democrats expressing a great deal or fair amount of confidence in it. Meanwhile, ratings of the legislative branch differ little by party (just five points), which is typical at times of divided party control of the U.S. House and Senate, such as exists today.

The 85-point difference between Republicans’ and Democrats’ views of the executive branch is the widest Gallup has recorded for this trend dating back to 1997, similar to the extreme political polarization recorded this year for Trump’s job approval rating.

Republicans’ and Democrats’ levels of confidence in the legislative branch have tended to diverge more when the same party controls the House and Senate than they do currently. That was the case in late 1998 and 1999 after Republicans retained majorities in both chambers during the 1998-midterm elections, and from 2007 to 2010 after Democrats gained full control in the 2006 midterms.

While higher than the average five-point gap recorded since 1997, today’s 24-point partisan gap for the judicial branch is similar to the gap seen from 2005 to 2008 and in most years since 2015. Regardless of the magnitude of party differences, the president’s party tends to view the judicial branch more favorably than does the opposing party, and that has continued under Trump.

Today’s relatively modest trust in the American people reflects similar ratings from Republicans (62%) and Democrats (57%), suggesting both parties have reason to be less than enthusiastic about the political acumen of their fellow Americans.

Bottom Line

As the country is engaged in critical efforts to combat the medical, economic and societal effects of the global coronavirus pandemic, Americans’ trust in the federal government to handle domestic issues is near its lowest point in Gallup trends since 1972, as is their trust in the executive and legislative branches, public officials generally, and the American people themselves.

The remaining bright spots in Americans’ views of government, at least for now, are their levels of trust in local and state governments — both of which have played key roles in responding to the pandemic — as well as the judicial branch.

Fearful and Angry About the State of the Country

According to a separate report by Pew Research, after the elections on November 3, the majority of voters said they continued to feel “fearful” and “angry” about the state of the country.

The polarization of America is one of the factors driving resentment on all sides. Aside from an uncontrolled outbreak of the coronavirus, politicians in D.C. have yet to pass a second stimulus package despite the U.S. economy continuing to shed jobs as companies cut back and shutter.

A November 20, 2020 report – Most voters are ‘fearful’ and ‘angry’ about the state of the U.S., but a majority now are ‘hopeful,’ too — by Amina Dunn said:

As the United States struggles with a surge in COVID-19 cases and ongoing disputes about the Nov. 3 election, majorities of voters continue to say they feel “fearful” and “angry” about the state of the country.

However, the share who say they feel angry has declined since June, while more voters now say they feel “hopeful” than did so then, according to a new national survey by Pew Research Center.

Today, 65% of voters say they are fearful about the state of the country, little changed since June. A smaller majority (57%) say they feel angry, down from 73% five months ago.

At the same time, a 56% majority of voters now say they feel hopeful about the state of the U.S., up from 47% in June. And while only about a quarter of voters (24%) say they feel “proud” about the country, that is 8 percentage points higher than five months ago.

Voters who cast their ballots for President-elect Joe Biden are much more hopeful than Biden supporters were in June: 72% now say they are hopeful about the country, compared with 42% then. There also has been a sharp decline in the share of Biden supporters who feel angry, from 80% then to 56% now.

Meanwhile, the share of Biden supporters who feel proud about the state of the country has tripled from a very low level in June, rising from 7% to 22%.

Trump supporters, by contrast, are now far less likely to say they are hopeful about the country than they were five months ago and more likely to be fearful. Only about four-in-ten Trump supporters (39%) feel hopeful, down from 53% in June. The share of Trump supporters who say they are fearful about the state of the country is 11 points higher than it was in June (56% then, 66% now).

As a result of these shifts in opinions since June, roughly similar shares of Trump and Biden supporters now say they are fearful, angry and proud about the country.

Among Biden voters, majorities in all age groups say they are hopeful about the state of the country. But those who are 65 and older are more likely than those in other age groups to say this, while those ages 18 to 34 are least likely to say this (83% of those 65 and older say this, compared with 72% of those 35 to 64 and 60% of those under 35). Similarly, while 29% of Biden voters who are 65 and older feel proud, that compares with 16% among Biden supporters under 35. Those under 35, in turn, are more likely than those 65 and older to say they are angry (63% vs. 49%).

Among Trump voters, those under 35 are somewhat more likely than others to say they are hopeful about the state of the country (46% of 18- to 34-year-old Trump voters, vs. 38% of Trump voters 35 and older).

The public’s overall satisfaction with the state of the country has changed little since before the presidential election. Today, about one-in-five U.S. adults (22%) say they are satisfied with the way things are going in the country; last month, 18% said they were satisfied with national conditions. However, satisfaction is substantially higher than it was in June (12%).

In October, before the election, Republicans and Republican-leaning independents were more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say there were satisfied with the way things were going in the country (30% vs. 7%). Today, similar shares of Republicans (23%) and Democrats (22%) say this.

Another November 13, 2020 Pew report — America is exceptional in the nature of its political divide — by Michael Dimock and Richard Wike said:

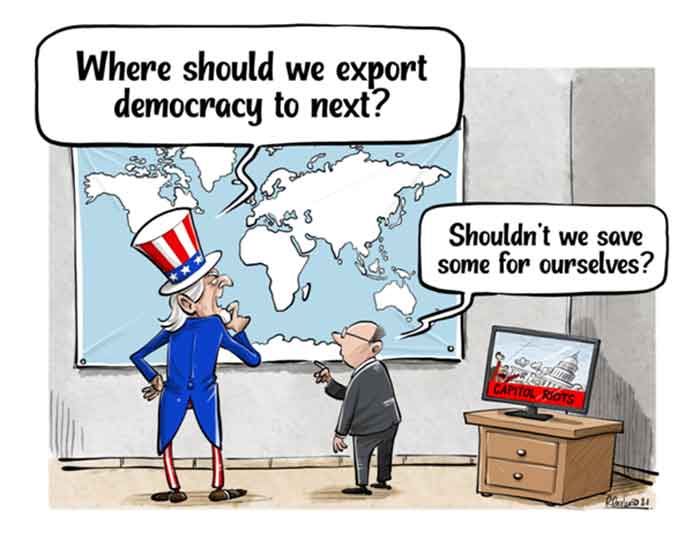

Americans have rarely been as polarized as they are today.

The studies we have conducted at Pew Research Center over the past few years illustrate the increasingly stark disagreement between Democrats and Republicans on the economy, racial justice, climate change, law enforcement, international engagement and a long list of other issues. The 2020 presidential election further highlighted these deep-seated divides. Supporters of Biden and Donald Trump believe the differences between them are about more than just politics and policies. A month before the election, roughly eight-in-ten registered voters in both camps said their differences with the other side were about core American values, and roughly nine-in-ten – again in both camps – worried that a victory by the other would lead to “lasting harm” to the United States.

The U.S. is hardly the only country wrestling with deepening political fissures. Brexit has polarized British politics, the rise of populist parties has disrupted party systems across Europe, and cultural conflict and economic anxieties have intensified old cleavages and created new ones in many advanced democracies. America and other advanced economies face many common strains over how opportunity is distributed in a global economy and how our culture adapts to growing diversity in an interconnected world.

But the 2020 pandemic has revealed how pervasive the divide in American politics is relative to other nations. Over the summer, 76% of Republicans (including independents who lean to the party) felt the U.S. had done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, compared with just 29% of those who do not identify with the Republican Party. This 47 percentage point gap was the largest gap found between those who support the governing party and those who do not across 14 nations surveyed. Moreover, 77% of Americans said the country was now more divided than before the outbreak, as compared with a median of 47% in the 13 other nations surveyed.

Much of this American exceptionalism preceded the coronavirus: In a Pew Research Center study conducted before the pandemic, Americans were more ideologically divided than any of the 19 other publics surveyed when asked how much trust they have in scientists and whether scientists make decisions solely based on facts. These fissures have pervaded nearly every aspect of the public and policy response to the crisis over the course of the year. Democrats and Republicans differ over mask wearing, contact tracing, how well public health officials are dealing with the crisis, whether to get a vaccine once one is available, and whether life will remain changed in a major way after the pandemic. For Biden supporters, the coronavirus outbreak was a central issue in the election – in an October poll, 82% said it was very important to their vote. Among Trump supporters, it was easily the least significant among six issues tested on the survey: Just 24% said it was very important.

Why is America cleaved in this way? Once again, looking across other nations gives us some indication. The polarizing pressures of partisan media, social media, and even deeply rooted cultural, historical and regional divides are hardly unique to America. By comparison, America’s relatively rigid, two-party electoral system stands apart by collapsing a wide range of legitimate social and political debates into a singular battle line that can make our differences appear even larger than they may actually be. And when the balance of support for these political parties is close enough for either to gain near-term electoral advantage – as it has in the U.S. for more than a quarter century – the competition becomes cutthroat and politics begins to feel zero-sum, where one side’s gain is inherently the other’s loss. Finding common cause – even to fight a common enemy in the public health and economic threat posed by the coronavirus – has eluded us.

Over time, these battles result in nearly all societal tensions becoming consolidated into two competing camps. As Ezra Klein and other writers have noted, divisions between the two parties have intensified over time as various types of identities have become “stacked” on top of people’s partisan identities. Race, religion and ideology now align with partisan identity in ways that they often did not in eras when the two parties were relatively heterogenous coalitions. In their study of polarization across nations, Thomas Carothers and Andrew O’Donohue argue that polarization runs particularly deep in the U.S. in part because American polarization is “especially multifaceted.” According to Carothers and O’Donohue, a “powerful alignment of ideology, race, and religion renders America’s divisions unusually encompassing and profound. It is hard to find another example of polarization in the world,” they write, “that fuses all three major types of identity divisions in a similar way.”

Of course, there is nothing wrong with disagreement in politics, and before we get nostalgic for a less polarized past it’s important to remember that eras of relatively muted partisan conflict, such as the late 1950s, were also characterized by structural injustice that kept many voices – particularly those of non-White Americans – out of the political arena. Similarly, previous eras of deep division, such as the late 1960s, were far less partisan but hardly less violent or destabilizing. Overall, it is not at all clear that Americans are further apart from each other than we have been in the past, or even that we are more ideologically or affectively divided – that is, exhibiting hostility to those of the other party – than citizens of other democracies. What is unique about this moment – and particularly acute in America – is that these divisions have collapsed onto a singular axis where we find no toehold for common cause or collective national identity.

Americans both see this problem and want to address it. Overwhelming majorities of both Trump (86%) and Biden (89%) supporters surveyed this fall said that their preferred candidate, if elected, should focus on addressing the needs of all Americans, “even if it means disappointing some of his supporters.”

In his speech, President-elect Biden vowed to “work as hard for those who didn’t vote for me as those who did” and called on “this grim era of demonization in America” to come to an end. That is a sentiment that resonates with Americans on both sides of the fence. But good intentions on the part of our leaders and ourselves face serious headwinds in a political system that reinforces a two-party political battleground at nearly every level.

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER