Narayan Govind Sagar, a 74-year-old farmer in Sangli district of Maharashtra, holds a Below Poverty Line ration card. He has four acres of land, but ground is rocky and there is little water, so farming is hard. Despite all this, though, he is quite parsimonious and managed to save Rs25,000. He went to the ICICI Bank at Khargani village in 2010 to deposit his hard-earned money in a fixed deposit. He was assured at the bank that he would get a handsome rate of interest that would double his money in five years; one year later, however, he was informed that he had an insurance policy, and would need to pay Rs25,000 each year as annual premium. He was warned that if he did not pay that sum, his earlier deposit would be forfeited.

Under pressure, and to save what money had already been deposited, he borrowed Rs25,000 to pay the premium. But that is hardly something he can keep doing each year. Now, he wants his money back, with interest. At the bank, though, he is told that what he has is not a fixed deposit but an insurance policy; that under the terms of the policy, no money is now due to him as he has forfeited the sum through non-payment of annual premium. He says he returned after five years to get the money back, but staff at the bank had changed and he was unable to lodge a complaint or follow up.

Sachin Srimanth Khilari, 28, is a farmer in Khargani, the village in which ICICI Bank has a branch. Khiladi dropped out of school after finishing Class 7. His family owns five bighas of land, and he also rears goats. He says he earns about Rs4 lakh a year.

He had approached ICICI bank with Rs2 lakh that he wanted to put into a fixed deposit in 2014, after the family sold some goats. The manager of the ICICI Bank in his village, he says, persuaded him to deposit the money instead into a policy that offered a more attractive rate of interest; he says he was promised a 15% rate of interest. He was also told that he would have to deposit Rs2 lakh each year as part of the terms of the policy, and he did not anticipate a problem with that.

His father later received Rs4 lakh after the partition of inherited land with his brother; Khilari’s uncle had agreed to pay Rs1 lakh later. When Khiladi deposited that money in the bank, the manager told him to add that amount too in his policy, rather than leave it idle in his account. He was told the rates of interest were better in the policy; he could make a deposit, he was told, on an old policy and pay in advance, before the premium amount fell due each year. When he received the Rs1 lakh that remained for the plot, that amount too was similarly “deposited into the policy”.

He had made four deposits in this time, and each time, he discovered later, a new policy was being sold to him. He was reminded of a pending premium by an official of the bank, and when he protested that he had actually deposited Rs8 lakh, with Rs6 lakh ahead of when his annual premium fell due, he was informed that he had not one but at least three policies. He would be required to deposit at least Rs6 lakh annually as premium. If he missed paying the premium, he stood to lose the amount he had already deposited.

Khiladi said he rushed to the bank, met the manager and explained that he had asked for only one policy, and did not understand how three different policies had been sold to him. Khiladi says the bank manager assured him that all was well; he said the lady who explained to him that he could forfeit his money had joined only recently and was mistaken. He was assured that he had only one policy, and the money could be availed in 10 years, if he paid his annual premium.

The procedure of tele-verification for such policies appears to be manipulated by bank staff – Khiladi said he received one call from the bank, and was instructed by the manager not to divulge too much and to only respond with ‘yes’ to the call. Under the norms, insurance policy sale also requires production of income tax returns documents, which were never asked in this instance. In two of the policies, Khiladi’s income is shown as Rs8 lakh per year – he claims the forms were not filled in his presence, and his income was exaggerated. Anti-Money Laundering (AML) guidelines of the Reserve Bank of India make it clear that the insurer is responsible for verifying the income of those seeking insurance; it is unclear how policies that required payment of Rs6 lakh annual premium could be sold to a man whose income is Rs8 lakh per annum, even if that sum is assumed to be his real income.

As word spread of the loss of money through such deposits, some villagers got together – four of them took a complaint to police at the Attapadi police station in Sangli district with the aim of lodging an FIR. Policemen, however, refused to file an FIR.

On October 17, 2020, as their attempts to get an FIR lodged failed, the four made an entry in the Aaple Sarkar website of the state government, launched five years ago to ensure that public services can be accessed as a right. The complaint was forwarded to the Superintendent of Police, Sangli Rural, but no action has yet been taken. Under the norms, action in such matters should be taken in three weeks.

Police inspector Bajrang Kamble of Attapadi police station said, “We needed expert advice on whether the terms of the contract had indeed been violated and a case could be made out, so we have sent it on for that purpose.” Asked how long the procedure might take, since it was over 45 days since the complaint was lodged on the Aaple Sarkar website, he said he could not tell precisely.

Sachin Khilari told Countercurrents, “I was surprised that a retired Deputy Superintendent of Police whose name was Sonawane (the reporter could not find out his first name) would turn up at the police station and begin negotiations with us. He has even called me a couple of times and assured me that my money would be returned, so long as I kept quiet and did not encourage others to make demands too. He said he had started work with ICICI about three months ago, I do not know in what capacity. While at the police station, I briefly lost my cool, and told him that he was retired and had nothing to do with the matter. But each time he was present at the police station, the officer who currently serves as deputy SP, Vita, was also present.”

This reporter could not get through to Sonawane at the phone number provided by Khilari; contact could also not be made with the officer in Vita to check what his role in this matter was.

An email seeking a response on what action is being taken to prevent such fraud on poor people was sent to top officials of ICICI Prudential, CEO NS Kannan and CEO of ICICI Bank Sandeep Bakshi. Shubham Mukherjee, head of corporate communications of ICICI Pru Life, responded seeking a meeting of ICICI Pru Life officials with this reporter. He was instructed to send an email, since a meeting would be unnecessary. He then wrote to the editor of Countercurrents, explaining, “We are a customer-centric organization and have sold millions of policies in our 20 years of existence in an industry which is strictly regulated by IRDAI (Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India). …We also have reasons to believe that the case details are being twisted and redressal being suggested is not in tune with IRDAI’s grievance redressal system. And hence all the more reason that we are given a chance to share our perspective.” Mukherjee sought a Zoom call with the editor of Countercurrents, and was told that he could convey his points to the reporter instead.

In his note to the editor, Mukherjee said, “A company statement on a complicated topic like this seldom does justice to the broader issue. Besides, it fails to capture our industry-leading customer metrics like the grievance ratio, which is one of the best in the industry. It’s therefore no surprise that this year we also won the FICCI award for excellence in customer service.”

Mukherjee send in a response to this reporter that did not address the question raised, about what was being done to prevent mis-sale of insurance to the poor. He laid the responsibility squarely on the regulator: “…have a robust grievance redressal mechanism as mandated by the Regulator, for the entire insurance industry…Importantly, the Regulator has access to view every grievance registered with the Company.” In November 2019, during a hearing of a PIL in the Rajasthan High Court on this matter, IRDAI, the Regulator, admitted that it had received 4,09,750 complaints of unfair business practice in 2018-19 alone. In a document submitted in court, IRDAI said, “It is impractical to investigate each and every complaint.”

This reporter had sought to know from ICICI Pru Life how many retired police officers may currently be engaged with the ICICI Group in Maharashtra; the question was left unanswered.

It may be pertinent to point out that an award for excellence may be a different thing from excellence itself. Former US President Barack Obama won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009, even though he was responsible for the deaths of several innocent civilians in drone strikes.

Meanwhile, without winning any award at all, Udaipur-based Nitin Balchandani has been aiding poor villagers in getting their money back. Balchandani, a former ICICI Pru Life employee-turned-whistleblower, has carefully documented over 350 cases of mis-sale of insurance by ICICI Prudential, through branches of the ICICI Bank in his state. Balchandani says he quit his job when he realized that insurance was being sold to people who he knew would be unable to keep paying premium.

Since 2012, when he quit his job at ICICI Prudential, Balchandani has been aiding poor villagers in the region near his home in Udaipur to file complaints with the IRDAI, Reserve Bank of India, the Serious Fraud Investigation Office, the Prime Minister’s Office and other authorities. ICICI Prudential filed a case against him, accusing him of stealing confidential information. That case was dismissed by the Rajasthan High Court in January 2018, since no evidence of wrongdoing was produced in court.

Balchandani has now formed a small office under the name ‘Insurance Angels’ to aid those who have lost money. Some of the people who have received their deposits back with assistance from him include an NRI businessman and a senior retired journalist from a well-regarded English national daily. Some of his clients have paid him a fee for his help in retrieving deposits. He drafts letters of complaint and pursues the matter until ICICI Pru Life is forced to act.

Balchandani said, “I have found that each time a case of fraudulent sale of insurance by bank employees is brought to the notice of authorities, attempts are made to pay back the sums owed and hush up the matter. However, fresh cases of fraud occur elsewhere. It is impossible to get the mainstream media to even report this matter. ICICI Bank perhaps has huge clout, given it offers advertisement revenue to media outlets. Even when fraud is reported and carefully documented, police officials do not act. I have single-handedly documented over 350 cases in Rajasthan, and now that I have uploaded videos on YouTube, people from Maharashtra too have seen them and reached out to me. The pity is that these are often poor people with meager sums as savings. They are also not aware of where to turn to for help. The literature that comes with the policies is in English, and some of them are illiterate, cannot read even Marathi properly. Imagine how hard it will be for poor farmers to negotiate with corporates if the new farm laws are actually implemented, when this is the case with deposits of such hard-earned savings!”

Despite all his efforts over the past eight years, Balchandani is amazed that the fraudulent sale continues, and that this matter of defrauding the very poor gets almost no media coverage at all, except on websites like The Wire.

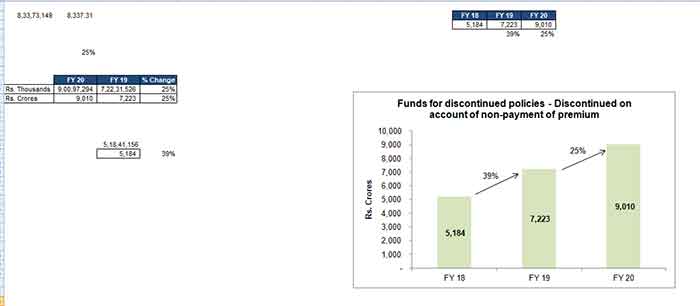

Meanwhile, a perusal of the financial statements of ICICI Prudential Life shows that over Rs9000 crore is listed under ‘funds for discontinued policies’; this sum has been rising steeply over the years.

Rosamma Thomas is a freelance journalist from Pune

SIGN UP FOR COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER