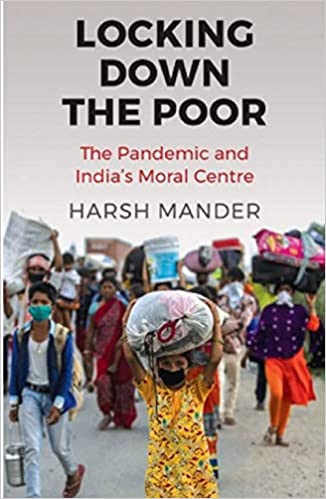

Covid pandemic will remain an important chapter in India’s history. This is not only for the public health challenge it caused but it also brought out the deeply hidden flaws, biases, prejudices of the state and society. It was a mirror reflection of the state and society we are living in. The book by Harsh Mander titled “Locking down the poor: The Pandemic and India’s Moral Centre” is an attempt to display these deeply hidden class biases reflected in Indian society.

The book is divided into 12 chapters and written in a narrative style. The author cites various examples to depict the situation of the ‘other’ who in this case are the Migrants, Muslims and Poor.

What followed the lockdown announcement was India plunging into one of the greatest humanitarian crisis other than partition and Bengal famine of 1943. India already placed low in ‘Global Hunger Index’ became a nation where hunger became much more visible. The poor lost their income source through which they could buy food. They suddenly had to line up in long que for their next meal. Employers stopped paying the workers. Landlords started pressing the workers for rent.

The initial call by the government to work from home, wash hands and maintaining ‘do gaj ki doori’ turned out to be cruel joke on India’s poor people. The society where there was already deeply rampant inequalities, none of the solutions suggested was applicable to a large section of Indian population. Two-third of India’s urban population was in no position to maintain physical distance. In a country, where five people share a single room and there are ten crore such families, this was inapplicable. This was inapplicable in Metro slums, where there is limited access to safe drinking water, sewage and toilets. Moreover, denial of wage income further cut into their capacities to buy water. The poor had already lost their income source.

The steepest wound inflicted by lockdown was on ‘several million migrant workers willfully forsaken by their government, by their employers and by a society whose very existence rests on their skill and labor’. With public transport suspended, inter-state movement banned 30 million inter-state migrants walked or cycled back to their homes. This was higher than the displaced populations during India’s partition. Middle class lives whose daily life is dependent on these migrants whether for erecting a home, plumbing pipes, fixing electricity or painting walls, serving homes, running auto-rickshaws saw the reality of migrants for the first time on the TV screens. In the act of movement of migrants towards villages ‘was the demolition of their faith and trust – in their employers, middle-class neighbors and government’. With no solution in hand, as the migrants started walking back governments was callous and even cruel blaming migrants for not being grateful to state’s food distribution, misled by rumors and being irresponsible in spreading the contagion.

Movement back to villages was a struggle as they had to face beatings of police, survive on biscuits, sleep on roads and railway tracks, hide in truck containers and cement mixers. Having exhausted their savings, they had to ask families in their villages to wire back money so that they could buy cycle to return back. Various stories of the returning migrants are cited by the author. Many died due to exhaustion, hunger, heat-stroke and accidents. Walking in hot conditions and lacking food, the body lost its capacities to produce energy. Cases of human endurance, including a case of a girl cycling with her father for over a 1,000 kilometers to reach home received publicity and praise but author points these need to be seen as manmade tragedies and used for reflection.

When the migrant workers wanted to get back home, there was low empathy shown in transporting them back. Conditions for travel by Shramik trains were made conditional – such as producing medical certificate, making it necessary to register online, payment towards travel made more expensive than its original cost, lack of arrangements made for food & water during the journey back to home. While being unfriendly towards migrants, state turned out to be friendly for its rich and middle classes. Under Vandemataram mission 10 lakh expatriates were transported back to the country, which included middle class students and Indians working abroad. It also transported back students from Kota in Rajasthan.

Many human stories of abandonment, starvation and cases of denial of rights as informal workers are brought out by the author. Many of them were historically dispossessed and living in extreme poverty. Even before lockdown, all types of rights – food security and various forms of labor rights such as job security, statutory wages, safe and healthy working conditions and social security were denied. They were already vulnerable. The lockdown only worsened the condition. While the harshest lockdown was imposed, it was the world’s smallest relief package. The period was also used for taking away labor rights in four states through imposing 12 hour working hours.

The relief measures fell short of the actual requirement. The package announced in the name of ‘Atma nirbhar bharat’ was primarily credit focused. Countries which were led by women Germany, New Zealand, Denmark, Finland and Taiwan turned out to be more sensitive to relief than countries known to be led by those considered strongmen such as India, US and Brazil.

The economic and health costs of the lockdown was huge. MSMEs were hard hit throwing 114 million workers out of employment in April 2020. Studies indicated Covid may cause extinction of about 30-40% smaller, informal firms. Daily earnings of informal women workers saw a deep decline. 18.9 million salaried jobs were lost during four months of Covid. During the first quarter of 2020-21, India’s GDP declined by 23.9%. The period saw severe disruptions in health services for non-Covid issues such as for diabetes, TB, immunization, anti-malarial care, safe delivery services or in need of services for dialysis, heart ailments, and cancer. Mental health issues saw an increase. Steep increase in cases of domestic violence was reported.

The author points to the manner in which the issue of Covid spread was communalized. Citing the ‘Tablighee jammat’ where Muslims from India and abroad had gathered for a religious event, the event was depicted as a major cause for spread. The fake news industry, IT cell and media built on this story and demonized a community. Similar larger religious gathering had taken place during the period, such as ISKON gathering, Sikh gathering, gatherings for Ram Navami at different locations. But no criticism of non-Muslim gatherings were made. Fake videos of how Muslims were intentionally spreading the virus through spitting on food, applying saliva, coughing on Muslims was in circulation. The incident was used to build anti-Muslim hate in the name of Corona Jihad. The propaganda led to attacks on Muslims, which included vegetable vendors, agricultural laborers. Other than communal dimension, using the racial dimension, those from North-east were taunted, shunned in the neighborhoods associating them with Chinese and linking them with spread.

During the lockdown the author points that the health infrastructure was poor with poor bed availability. Getting bed and hospital admission became difficult. Where patients found admission, the bills were inflated in corporate hospitals. The lockdown period was not utilized to address shortage of hospital beds, ventilators, ICU facilities, personal protective equipment’s (PPEs). Testing rates remained quite low in comparison to global rates. There were hardly any consultation done with epidemiologists, social scientists, public health experts, medical practitioners with experience of working with marginalized, collectives of workers, social workers and activists for addressing the challenges. Official communication was one sided with hardly any press briefings.

There were many models which the state could have followed. South Korea had adopted the ‘Trace, Test and Cure’ model. In Kerala, a vibrant community support was built to control surge of the pandemic. In Dharavi, intensive screening, testing, isolation and community participation was adopted and a disaster was averted.

The author points that lockdown was wrong in principle itself. It was disastrous public health, disastrous economics, disastrous sociology and unconscionable public ethics. In a country with embedded economic and social inequalities, this was unforgivable. Countries which resorted to other measures showed more effective results. The Chinese strategy of limited lockdowns in Wuhan and Pakistani strategy of not going for stringent lockdown taking into account working class requirements were able to bring down the curve earlier.

The author points that India could have consulted a mix of public health experts, epidemiologists, economists, social scientists and studied global experiences. A model similar to South Korean model of ‘Trace, Test and Cure’ could have been adopted. It could have gone for limited lockdown without effecting the poor. Unconditional cash transfers of Rs. 7,000 could have been made and supported through universal public distribution system. Government could have arranged repayment of loans of MSMEs for six months to prevent it from sinking. Migrants could have been given time to return to their homes through operating passenger trains. Water supplies could have been supplied in slums. It could have through ordinance prevented private hospitals to charge exorbitantly from Covid cases. Stadiums, Universities and Hotels could have been converted to temporary Covid hospitals. Public and private corporations could have been incentivized to expand production of PPEs, testing kits, ventilators and medicinal oxygen. Front line health workers could have been regularized. Public spending on relief could have been increased. The author points that instead of going for a harsh lockdown, perhaps the policy makers could have thought of Gandhi’s talisman which is to consider the poorest and the most vulnerable before taking a decision.

Quoting Arundhati Roy, Mander points that COVID-19 is a virus but also an X-Ray that exposed the desolation called civilization. It depicted a broken society, where aspirational classes are cut off from the reality of working poor and bereft of empathy and solidarity. The lockdown shows the exile of the poor from our conscience and consciousness. With the privileges of income, savings, home, online entertainment the middle classes welcomed the national lockdown. But they were indifferent to the reality outside their homes.

The book is an essential reading and a commentary on the state response to the pandemic. It forces us to look into how in an unequal society, the poor get further marginalized as they get far removed from the view of official radar in public policy decisions. Drawing human stories from the pandemic and through a commentary on the state of affairs, the author points the need for being more empathetic towards India’s poor, making them a part of conscience and consciousness and bringing them into the center of the moral universe. The book also consists of some positive stories of hope, empathy and solidarity.

T Navin is a writer and works with a Research Institute

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX