The centre’s estimates are flawed and give the impression that the economy has not only weathered Covid-19 but overcome pre-existing difficulties. But in reality, demand is short, dampening economic revival.

Officially, the “growth in GDP during 2020-21 is estimated at -8.0 percent as compared to 4.0 percent in 2019-20”. Further, “GDP at Constant (2011-12) Prices in Q3 of 2020-21 is estimated” as 0.4 percent. This is stated in the press note on The Second Advance Estimates of National Income, 2020-21, released on February 26, 2021. The Q3 data is for October to December 2020.

The implication is that the economy has recovered from the recession in the first half of 2020-21 and is once again growing, even if marginally so. If this is true, then in the final quarter of 2020-21, the economy should recover further. But the issue is whether the economy will recover to its growth rate of 2019 anytime soon. The economy had already slowed down to 3.1 percent in the last quarter of 2019-20, just before the pandemic hit. This was a decline from 8 percent achieved eight quarters back. In brief, the economy was already facing headwinds before the pandemic hit it in March 2020.

If the economy had started to grow in Q3 of 2020-21, does it mean that it has not only weathered the pandemic and lockdown induced problems but also largely overcome the pre-existing difficulties which had led to the sharp slowdown over two years? This question raises three possibilities. First, the pickup has automatically happened after a sharp decline in the economy. Second, it is the result of the policies put into place by the government. Finally, official growth data is incorrect given data and methodological deficiencies.

OFFICIAL DATA FLAWED

The government and the RBI use high frequency data to estimate the quarterly growth in the economy and predict the advance annual growth. A perusal of the list of variables used to estimate the growth rates shows that most of them are from the organised sector and a few from the unorganised one.

Thus, the data are incomplete. Agriculture is the only component of the unorganised sector whose data is used for quarterly estimation. But here also problems arose during the lockdown period. As this author has been pointing out, limited data for agriculture was available and it was assumed that targets were achieved. This was definitely not the case for perishables like fruits and vegetables which rotted in the fields or for poultry and milk, and these items constitute half the production in agriculture.

Thus, during the lockdown, the agriculture sector also declined by at least 10 percent rather than the officially claimed growth at 3.4 percent. No wonder farmers lost incomes and are protesting for the last 100 days.

For the rest of the sectors, the press note says that “the approach for compiling the advance estimates is based on Benchmark-Indicator Method” and “extrapolation of indicators”. Thus, the estimates are approximations. Further, it says, most “information (is) available for the first 9 months”. This methodology is problematic when the economy has experienced a shock and especially a sharp one like the lockdown neither the earlier benchmark indicators nor extrapolations will be valid. So the official estimates become guesses and are likely to be incorrect.

The press note admits that the lockdown had an “impact on data collection mechanisms”. Further, the note says this “will have implications on subsequent revision of these estimates”. Finally it says: “Estimates are, therefore, likely to undergo sharp revisions” and “users should take this into consideration when interpreting the figures”.

This raises the further point that if lockdown prevented data collection in Q1 and Q2 of 2020-21, much of it cannot be collected later on. Thus, the data for these quarters will remain permanently flawed.

Consequently, calculating the growth rate for these quarters and for 2020-21 as a whole, will have errors. The implication is that the official growth data cannot be relied on. Is there an alternative to it?

CURRENT GROWTH

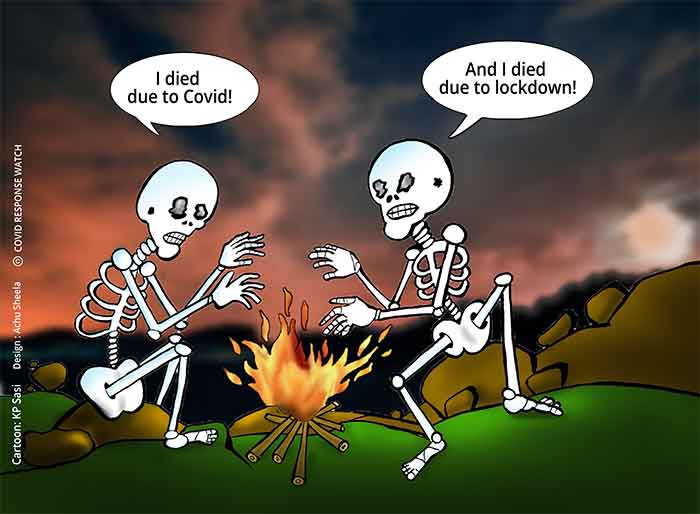

Lockdown is a voluntary cessation of activity. People do not go to work, so factories and offices stop working except for some essential production. Very few are able to work from home in India. So most economic activity ceased in April and May 2020 and the GDP fell drastically. As the economy unlocked, activity revived and the GDP picked up.

The issue is whether economic activity picked up to the pre-pandemic level in Q3 of 2020-21 as the official data indicates. As already argued, the official data is based largely on some indicators collected from the organised sector. Even the complete organised sector data is not available. For instance, data for companies is based on reports to the stock markets but only a few hundred company reports are available at any point of time and not all companies’ reports.

Some sectors of the economy have done well since demand for their products and services increased during the pandemic. For instance, pharmaceuticals, FMCG, telecommunications and IT sector were in great demand. Due to curtailment of public transportation and other reasons, demand for personal transportation has shot up and the automobile industry has grown.

But for the entire manufacturing and services sectors, demand decreased due to decline in employment and consequent fall in demand. People are also worried about another wave of infection, so consumer sentiment remained low even in January 2021. Due to the overall decline in demand, capacity utilisation is at 65 percent according to the RBI governor. That is way below its level in January 2020. As a consequence, investment remains below last year’s level.

A decline in consumption reflects in both reduced output and investment compared to the previous year. In turn, this reflects in low credit off take. The RBI data for January 2021 shows this. The decline is particularly marked in the case of large industry which is responsible for more than 80 percent of the credit taken. The implication is that large industry has not yet recovered to the 2020 January level in January 2021 which is the first month of Q4. So one cannot conclude economic recovery in Q3 based on organised sector data.

UNORGANISED SECTOR

The unorganised sector was very hard hit and has not recovered to its January 2020 level, as the limited data available indicates. Demand for work under MGNREGS remains high and reports suggest that many demanding work under it are not able to get it since funds are exhausted. Also, instead of 100 days of work per year for one person per family, only about 45 days of work has been available. This, in spite of the budgetary allocation having been increased from Rs 60,000 crore to Rs 1.1 lakh crore.

A recent study points out that 20 percent of those who lost work during the lockdown have not been able to regain it. Data also indicates that many have simply dropped out of the workforce, especially women.

AIMO has been reporting that many small businesses are closing. Further, 20 percent are unable to repay EMIs and are likely to default. The RBI has been anticipating a rapid rise in NPAs in the coming months. Further, the rise of e-commerce has been at the expense of brick and mortar stores. CAIT has been saying that many small traders will have to shut shop.

This example also points to the growth of the organised sector at the expense of the unorganised one as demand has shifted from the latter to the former. This leads to an over-estimation of the growth rate of the economy.

Many contract services have not been able to revive to their pre-pandemic levels due to fear in the minds of customers. For instance, services of taxis, beauticians, hair dressers and gyms remain below last year’s levels. Similarly, transportation, travel, tourism, hotels and restaurants have not gone back to their pre-pandemic level of operations. This is true both for the organised and unorganised sectors. In brief, not only has the unorganised sector not recovered to January 2020 levels, even many parts of the organised sector have not. So the Q3 data cannot be relied on.

CONCLUSION

The government, instead of boosting demand, has heavily tilted in favour of supply side policies. Such policies, even if they are the correct ones, will impact the economy over the medium and long term.

So when demand is short and capacity utilisation low, investment will not revive and economic growth will remain down and the long term goal would not be achieved. Supply side policies also lead to greater inequality and that further impacts demand, as has been seen since the time of demonetisation.

Unfortunately, Union Budget 2021-22 does little to check the growing inequality and the stock markets are fuelling greater inequality. Both these trends will further dampen the prospects of economic revival in India.

(The writer was Professor of Economics, JNU, presently Malcolm Adiseshiah Chair Professor, Institute of Social Sciences. He is the author of Indian Economy’s Greatest Crisis: The Impact of the Coronavirus and the Road Ahead (Penguin Random House).

First published: indialegallive.com

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX