Moumita Alam’s debut poetry collection The Musings of the Dark is a powerful poetic assertion of dissent. Dissent against what? Against state sponsored violence against Kashmiris, violence against anti-CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act) protesters at Shaheen Bagh, violence against migrant labourers, daily labourers during Covid 19 pandemic. She also voices her dissent against structural violence of casteism, fascism, violence against women and weaker sections of society—the poor, the minors, the marginalized, the minority, the underprivileged, victims of rapes, riots. Darkness, Deaths, diseases, shocks at human rights violations, poverty, denial, disdain, blood, bullets, pain, suffering, demand for justice, quest for castles and classless society, drapes her world. Her poems are tinged with notes of sadness, bitterness, anger, despair. ‘The womb of nights are barren/ with no embryo of lights?’ (‘Good Night’, 107). They are raw, violent, bold, direct and powerful. But she argues, asserts, resists, and prevails in the end with her unflinching belief, ‘Revolution will come for sure at the dead of the night’ (‘Prayer for Revolution’, 55). Alam’s poetry crosses boundaries of castes, classes, creeds, continents.

The Musings of the Dark has four sections: ‘The Lost Paradise’ has 27 poems; ‘Shaheen Bagh Poems’ are 15; ‘I Can’t Breathe…’ has 39 and the last section ‘Love, Lost and Lust Poems’ 18. But the said categories blurs if we closely look at the issues her poems unearth. Some poems are political, some social, some inimitably personal. Poems included both in ‘The Lost Paradise’ and ‘Shaheen Bagh Poems’ are hallmarks of her protest against political violence unleashed by abrogation of Article 370 and 35A in Kashmir and the passage of CAA. The poet is deeply shocked, shattered, and in response to the said trajectories she records her wounds:

“Don’t let the bloody fascists dictate

Our hearts

let’s prove them

land they can rule not our hearts.” (‘To my Friend Who Lives in Imposed Graveyard’, 22)

Or

“we often end up our journey

at our starting point

Still we carve to travel our times

with galloping hooves and stars in our eyes.

Some end half circle path with bullets in chest

And pallets in eyes” (The Journey without Destination, 35)

In the name of development fascist rulers imposed Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) on Kasmiris and denied their right to freedom and self-determination, made the ‘heaven on earth’ a forgotten land of ‘half-widows, orphans,/ cloven vaginas, bleeding breast’(‘Development’, 44), a land where ‘bullets are far cheaper than chocolates’ (‘For the Boy Who could have Lived More’, 38).

Alam’s Shaheen Bagh poems challenge police brutality on peaceful protesters against CAA at Shaheen Bagh. She records the communal killings taken place in ghettos of Godhra, in the valley of Narmada, in Muzaffarnagar, in Nellie or on the bank of Jhelum, in the forest of Bastar, in Kucheipedar or in lush land of Nandigram, Marichjhapi, in Jaffrabad, Maujpur, Chand Bagh . ‘All the cities of mine are smelling warm gun-powders/ the sirens of the khakis, and that killing shout’ (‘Where is my City?’, 50). Her irony is apparent in ‘Busiest Persons’, only the grave diggers have hay day. They tirelessly digging grave for the ‘million hands, legs, eyes, stomachs, intestines’ of the dead routinely found in Kashmir, Syria, Palestine, Libiya, Iraq, Yemen. She mocks ‘the dead conscience/ Of the left, right, centre, liberals’ (p.51). She protests against the so called nationalist fads, the bhakts who openly chant in frenzy, ‘Goli Maro/ Khatam Karo/ Rape karo’. They don’t want Azaad, Maryam or their synonyms. Her pain and anger find expression in such lines:

“The would-be Azaad wobbled every time

THEYspurned at his mother’s protruding belly

THEY only broke the neck of Maryam

to teach parents a lesson of nationalism” (‘Azaad and Maryam’, 62).

Alam’s Covid poems portray woes of the wretched of our land—the poor, the daily wagers, the migrant labourers. Drawing room lovers bathed in cologne may celebrate government’s ‘stay at home’ order. But what will a hawker do?

“I dream every night to sell three melons more

to have two roti extra

and be able to buy a cotton

frock for my daughter” (‘Grave in Home’, 71).

The tragedy Dharmveer who had to cross 2000kms by cycle for ‘one gulp of boiled rice’ from his mother at home, died at midway, and a ‘petal kissed his dead lips’, ‘In big cities the makers live in graveyards/ And the lumpen dead souls/ have big buildings’ (78), the loneliness of the old and young , ‘The roads are full of empty hearts and dreamless eyes’, (80), ‘nights and the days all are/ sewn in the monochromatic silence’ (100), ‘No kiss. No smooches. No hug. No sex.’ (‘self-Quarantine’, 96), the misfortune of Mangoo Ram who is walking from Delhi to Munger without food or water and in one day he may be found ‘like the carcass of the cows’ by the roadside, (86)—hammers at our conscience. Her ironical attacks on the stupidity and stolidity of Indian educated, literate, ill-literate mass who bang thaalis, beat dufflis, clap and clap to ‘defeat the sounds/ of millions losing job’ during pandemic is a bitter pill of reason and conscience:

“and we are madly happy

banging thaalis, glasses, cylinders

bedpan, potty seats, sprained pots,

used unused mugs of toilets,

stools, and the confused madman of the roadside

with no utensils

is dangling his penis in delight;” (‘The Great Indian Thali Banging’, 93). ‘the wailing of the doctors, nurses/ for the gloves, masks/ ventilators, test kits’ is silenced by the chaos. ‘Millions of diyas and candlesticks are/burning in my city/ the darkness of the night seems more dark/

today! (‘Cities in Blackout’, 84). And her attacks on insanity of Indian mass comes complete with her asking: ‘Unperturbed by the noise or crying the cow is chewing grass’, ‘peeing on the same food it is eating,’ ‘pooping on the very place wherein it’s sitting.’ ‘Is not the cow a great teacher?/ or are we not the master of the cow?’ (‘The Cow’,108). Freedom is ‘cosmetic’. It has lost its way leading us to an arid land of blood, betrayal, hatred, where freedom equals beastly living, tongue-tied, head drooping, or helplessly agreeing with everything like Faulkner’s Darl in As I Lay Dying (1930) who reckons the mockery of ‘love’ his family bestows on him and protests in madness yes yes yes yes yes yes yes yes.

Alam’s ‘Love, Lost and Lust poems’ is too intimate. Of course there is a protest against patriarchy, against her ‘chained sky’, ‘I looked up to the sun/ but the sun is man’ (‘Mother’, p. 54), ‘she is a good girl/ she never asks for sex/ orgasm or no orgasm/ does not matter/ she is a good girl/ we possess her all’ (‘Our Relationships’, 135), ‘Now it is your responsibility son/ The burden changes hands and/ another man’s son become the/ Papa’s son/ his own daughter was a responsibility./ the papa felt relieved for the first time/ After her birth/ Now he has only son and son. (Homecoming’, 133). But there are also agonies of a loved heart betrayed by her love. ‘I sign the final divorce paper/ but the paper is burnt/ It can’t kill the memories/ the memories chase my breath.’ (Move On’ 132). Her appeal to her love is to love her as a human being, not to ‘tear apart the hymens to satisfy only/ your male ego’, not to ‘scratch the skins like/ a butcher skinning off a dead goat’, ‘Do learn, oh boy/ a female body/ has many more than/ two silky roads with/ the Carfax in its centre.’ (Do Learn how to Love’, 126). She paints the wounds a divorcee has to undergo. In fact lust engulfs the males she is familiar with. They pine for her bad luck, and as if to fill her empty sky they want ‘hard sex’. What a betrayal of the benevolent!

Alam is also concerned with environment ‘We poisoned the rivers/ destroyed the forests/ shot the flying birds/ and killed our brothers to/ celebrate colours of victory’, ‘on the pond by the mango garden where the birds/ had their kingdom/ We built palaces to make us / proof against bird’s song’ (The Lost Decade’, 98).

Alam’s collection is attuned with Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s immortal lines, ‘Bol, ye thora waqt bahut hai/ Jism or zaban ki maut se pahle / Bol, ke sach zinda hai ab tak/ Bol jo kucch kahna hai kah le’. Alam is a powerful voice. But she could have been more precise.

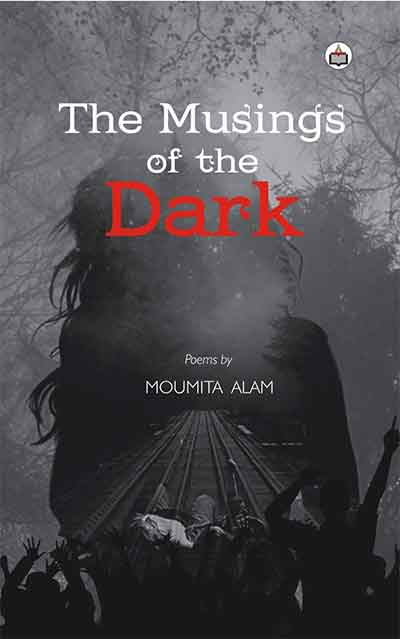

The cover of the collection is impressive and has an aesthetic appeal.

The Musings of the Dark

Moumita Alam

Authorspress, New Delhi, 2020

ISBN: 978-93-90155-59-0

Page: 142

INR: 295 ।$ 15

Abu Siddik teaches at Plassey College, West Bengal, India. He is a bilingual author and has been published in India and abroad. He has three critical books— Representation of the Marginalized in Indian Writings in English (Falakata College Cell, 2015), Misfit Parents in Faulkner’s Select Texts (Authorspress, 2015), Banglar Musolman (Sopan, 2018); two poetry books and a short story, published by Authorspress in 2020 —Rugged Terrain, Whispering Echoes, A Birdwatcher and Other Stories. Website: www.abusiddik.com

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX