Health expert Srinath Reddy on India’s unpreparedness for the second wave, the danger of variant B.1.617, and waiving patents on life-saving medicines

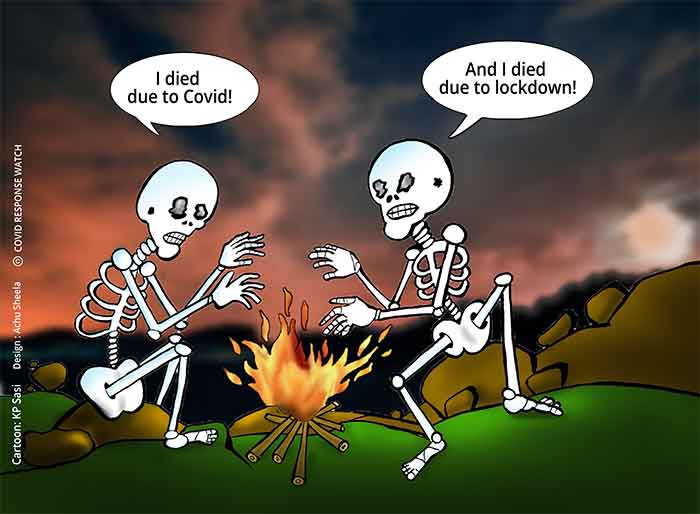

India’s second Covid-19 wave has been particularly vicious. On Monday, 366,161 new infections and 3,754 deaths were reported by the health ministry. We’ve seen hospitals run out of oxygen and beds, morgues and crematoria overflow, and bodies washed up at the banks of the Ganges, while states all around India introduced and expanded strict lockdown and containment measures. Can you give us a sense of the epidemiological situation right now, and how it could get to this point?

Obviously, India is now facing a huge challenge in the second wave, which it did not face during the first one. This is partly because we were caught totally unprepared. There was the very incorrect impression that India might escape the second wave because of herd immunity. This was an assumption which is both scientifically false and operationally disastrous.

The ferocity with which the second wave hit was however unexpected, even by people who believed that there would be a second wave. That’s because, apart from the original virus, a number of variants have entered India, and we had a completely open society for the variants to travel, unchallenged, on the superhighway, infecting a very large number of people.

On top of that came the number of super spreader events during the last four months, with campaigns for elections to both the local bodies and state assemblies, as well as a number of large religious gatherings, unrestrained social celebrations and unrestricted travel. All of these contributed substantially to the huge second wave.

Some of the areas which were heavily affected in the beginning are now seeing improvements, like Mumbai and the state of Maharashtra. Delhi is also beginning to show some signs of improvement in terms of the overall numbers of infected.

In a recent IPS interview with Margareth Dalcolmo, a leading health expert from Brazil, she highlighted the lack of social support and assistance as the most crucial failure of the Brazilian Covid-19 response earlier this year. In short, if people are starving, you cannot expect them to stay at home. With the measures now in India, especially thinking about the post-lockdown period, is there enough social support for the population to avoid transmission?

This is a challenge, but the situation is very different across different parts of India. That’s because we have a federal structure, and the individual state governments are responsible for meeting the essential needs of the people. Of course, the federal government can and should provide income support to those people who are unable to work because of the lockdowns and who are very vulnerable, and that’s a demand that’s been made.

But there are very many ways in which the governments of the provinces of the state, and even local governments. so-called village panchayats, and the local urban body, can play a big role in providing provisions to people who are locked up in their houses, who are isolated or quarantined.

There are some states who do it very well, like Kerala, Tamil Nadu or Odisha. There are some other states which are not doing it well. While we also need policies nationally to provide social support, local bodies and village level bodies also need to implement policies which are much more humane and equity-oriented.

Earlier this week, the WHO reclassified the triple-mutant Covid variant spreading in India you mentioned as a “variant of concern,” indicating that it’s become a global health threat. How concerned are you about the spread of the variant and its mutations in India and beyond?

Actually we have three variants currently active in India.

First is the Kent or the British variant, B.1.1.7, which came probably came to India after it surfaced in the UK in September last year, though Britain only declared it to the world in December. But obviously there was a lot of travel from Britain until very recently. This variant has established itself in the state of Punjab, in Delhi, Haryana, and it’s still active there, and it has spread to some other parts of India as well.

But the variant of concern that’s been announced by WHO, B.1.617, is the so-called double mutant from the state of Maharashtra, a mutant that carried some features that have been noted previously in variants in South Africa and also in Brazil. Now we also see that it has an additional mutation which has been seen earlier in California, and as a result, it carries a much greater threat of higher infectivity.

There’s also a third variant called B.1.618, which has been identified in the state of Bengal, and that seems to be spreading in the eastern region of the country. With all these three variants and the original virus still around, there is a considerable impact on infection rates, unless we severely restrain the virus and its variants through effective control of transmission.

That’s why many states have gone into lockdown or near lockdown, and therefore some of these measures are likely to have an impact soon.

But the big challenge is: what happens after the lockdown? How well can we control the transmission afterwards?

In terms of vaccine escape, however, the good news is that while there may be some impact on the efficacy of vaccines, at least the Indian-made vaccine seems to be acting against all the mutants. And even the AstraZeneca vaccine seems to be having some effect.

It’s not a complete vaccine escape challenge right now. It’s more one of higher infectivity.

As you mentioned, there’s the short-term measures – like the lockdown and other the containment measures – to reduce the spread of the virus, and the question of what to do afterwards to avoid transmission? But then, there’s of course also the long-term question of how does India get out of it for good. India is the world’s largest vaccine producing nation in the world, but as of May 10 Monday had just fully vaccinated 34.8 million people. What went wrong here?

Unfortunately our vaccination programme was misguided by the assumption that there won’t be a second wave, and therefore we could spread out our vaccination efforts over several months. Initially, the idea was to vaccinate health workers and other essential workers, then the vulnerable population above the age of 60 and those with comorbidities above the age of 45. In fact, these three identified groups were supposed to be vaccinated after September, and then we would open up to others. By that time, it was thought that apart from the two vaccines, which just received regulatory approval, there would be other vaccines that would be manufactured in India, either having been developed in India or licenced for manufacture in India.

All of these were tragic miscalculations based on the false premise that there won’t be a second wave. When the second wave erupted with great ferocity, it became very clear very quickly that we were short of vaccines. Therefore the export was now stopped and the imports are beginning. There’s also an urgency to try and produce more in India. The government has started funding vaccine companies, and it is going to be a bit of an uphill struggle for the next two or three months.

Last year, India and South Africa requested a waiver on patents related to Covid-19 vaccines and treatments at the World Trade Organization that, to the surprise of many, has recently received the support of the Biden administration? One of the main arguments against the waiver claims that it wouldn’t really help speed up manufacturing or expand manufacturing of vaccines. Do you concur?

Intellectual property rights have actually done a lot of damage(to) a global response to this pandemic by withholding access to essential technologies. But we must recognise that these technologies are not just confined to vaccines. Even in vaccines, it’s not just the finished vaccine product, it’s also the raw materials which have been so far been restricted, for example, by the United States, because of the Defence Production Act.

It’s not as though the pandemic is going to be over in two months’ time, particularly with a very low proportion of the global population vaccinated. With having very vulnerable populations, unvaccinated, we are going to see the pandemic prolong. It’s absolutely important for us to build global capacity to face this pandemic, and also to prevent new pandemics coming.

We have to be absolutely clear that the world has to be capable of producing more vaccines and treatments, and distributing them in an equitable fashion. That is why I believe the proposal tabled by India and South Africa is absolutely appropriate, and even though it may not immediately land us with vaccines in a month’s time, as the year progresses, our capacity to produce vaccines will be certainly much higher. However, it’s not just about vaccines but other technologies too.

Beyond the patent waiver, is there something that you think the international community – and Europe in particular – should do to show solidarity with India?

Any gesture of solidarity is most welcome because we need a global thrust to counter a global threat. We are not fighting this battle alone. It’s absolutely important for us to recognise that whatever we can do to help each other is very important, and even if it’s not going to make a huge difference immediately, it’ll come as a moral booster for a beleaguered country.

In concrete terms, if we can get access to vaccine stock which has been unutilised, like for example, AstraZeneca stocks in the US, that would help. Some stocks may be lying around in Europe. Johnson & Johnson is still under some cloud, so there will be some unutilised orders which maybe can be diverted to India.

Then, there is an issue of oxygen concentrators and oxygen generation plants, which are being supplied fairly liberally by countries in Europe as well as elsewhere. Moreover, in terms of new drugs that may be coming up, which may help to save lives, sharing them will be very helpful. There is another area that we still could do with more, personal protection equipment for a large number of frontline health workers as well as hospital workers and laboratory workers. There can never be too much of that.

***

This interview was conducted by Daniel Kopp.

Courtesy: ips-journal.eu , Interviews 14.05.2021

International Politics & Society is an online magazine covering sociopolitical issues affecting Europe and the globe. Published by @FESonline

https://www.ips-journal.eu/interviews/tragic-miscalculations-based-on-a-false-premise-5183/

Prof K Srinath Reddy is President of the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) and formerly headed the Department of Cardiology at All India Institute of Medical Sciences. Prof Reddy is the first Indian to be elected as Foreign Associate Member of the National Academy of Medicine (formerly Institute of Medicine) of the National Academy of Sciences, US.

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX