India’s social sector expenditures are amongst the lowest among all major economies of the world. In this concluding part of our budget analysis of Union Budget 2021-22, we present proposals on how the Centre can more than double its social sector expenditures.

Part I: Snapshot of Subsidies Given to Rich in Budgets

According to the Economic Survey, the annual document on the state of the economy, prepared by the Ministry of Finance under the supervision of the Chief Economic Advisor of the Government of India, the total social service sector expenditure of the government (including both Centre and States), has been below 7% of the GDP during the first four years of the Modi Government. In this year’s Economic Survey (for fiscal 2020-21), the government claims that it has risen to 7.5% of GDP in 2019–20 RE and further to 8.8% of GDP in 2020–21. But just like it has been doing for other statistics, the government has been indulging in exaggeration of its social sector expenditures too. For instance, the Economic Survey 2018-19 had claimed that the social sector expenditure that year was going to be 7.3% of GDP; next year, the Economic Survey 2019-20 stated that social sector expenditure of 2018-19 (revised estimate) was expected to be 7.6% of GDP; but this year’s Economic Survey 2020-21 admits that actual social expenditure for 2018-19 was only 6.7% of GDP. We do not expect actual social expenditures for both 2019-20 and 2020-21 to be above 7% of GDP.

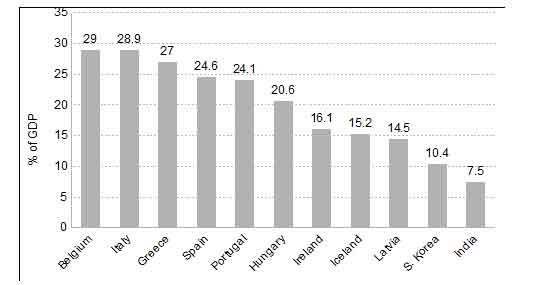

But even at 8.8% of GDP, the government’s social sector expenditures are way below those of developed countries. Thus, for the last many years, the average social sector expenditures for the 27 member countries of the European Union (EU–27) have at around 30% of GDP. In fact, India’s social sector expenditures are “woefully below (India’s) peers” too, as admitted by the RBI in its annual assessment of the union budget some years ago (see Chart 1, that is based on figures given by the RBI in this report). And since all these countries have per capita GDP much higher than India, it means that India’s actual, per capita, social sector spending is much lower than what these comparative figures suggest.

Chart 1: Social Sector Expenditures as % of GDP[1]

Despite these already low social sector expenditures, the Modi Government has reduced the Centre’s social sector spending on several important social sectors like education, nutrition and pensions in its successive budgets since it came to power in 2014 (we have discussed this in our previous articles on the budget – parts 3 and 4). In healthcare, which is in such deep crisis that the country has become the disease capital of the world, total Central government expenditure on health continues to hover at a dismal 0.3 to 0.35% of the GDP since 2014!

Even after the pandemic struck the country in early 2021 and the economy collapsed due to the lockdown, pushing crores of people to the edge of starvation, the government refused to increase its social sector expenditures by a significant amount. The relief package announced by Prime Minister Modi himself of Rs 20 lakh crore, equivalent to almost 10 percent of the GDP, turned out to be sheer bombastry of the highest order. The bulk of the financial assistance promised by the government was in the form of loan offers; the actual expenditure made by the government from its budget, which alone can be called a ‘relief package’, was just around Rs 2 lakh crore, or one-tenth of the amount announced by the PM, a ridiculous sum as compared to the scale of the massive economic devastation being faced by the people. It was the lowest relief package amongst all the major economies of the world.[2]

Why is the government not willing to increase its social sector expenditures? The government claims that it does not have the money, that it is facing fiscal constraints; just recently the finance minister claimed that the government’s subsidy bill is becoming “unmanageably high”; mainstream economists also claim that the government is financially constrained and should rationalise its subsidy bill—a euphmism for saying they need to be reduced; intellectuals writing in the media express delight whenever the government cuts its social sector expenditures.

All of them are lying! That the government doesn’t have the money is humbug. The real reason why the government doesn’t want to increase its social sector expenditures is because it is doling out enormous amounts of subsidies to the big corporate houses and the rich. These subsidies are to the tune of several lakh crore rupees every year! Obviously then, it is not going to have money to give for social welfare expenditures directed at benefiting the poor.

In a deft use of language, while the breathtaking ‘subsidies’ given to the rich are euphemistically called ‘incentives’ and justified as being necessary for ‘growth’, the social sector expenditures—whose purpose is to provide the bare means of sustenance to the poor at affordable rates—are condemned as ‘subsidies’, as being wasteful, inefficient, benefiting the middle classes rather than the poor, promoting parasitism, and so on.

Here is a snapshot of some of these subsidies being given to the rich:

a) Tax Exemptions

During the seven years it has been in power, the Modi Government has given tax exemptions to the rich—in corporate taxes, income taxes and excise duties—of several lakh crore rupees every year. An analysis of the Union Budget documents reveals that these exemptions total at least Rs 38 lakh crore over the period 2014–21.[3]

Because of such tax concessions to the rich, the overwhelming majority of the ultra-rich in the country pay hardly any taxes. Data made available by the Income Tax department reveals that in 2017–18, just 20 individuals paid a tax of more than Rs 50 crore.[4] This, despite the fact that in 2018, according to the Forbes list of world’s billionaires, India had 141 dollar billionaires!

The rich are having a gala time. India’s personal income tax collection both as a percentage of revenues and as a percentage of GDP is much lower than not just the USA and OECD but also the BRICS countries (as a percentage of GDP, personal income tax in USA was 10%, around 8% for the OECD countries, 5% for China, 3.6% for Russia, and 8.5% for South Africa, but was just around 1% for India.)[5]

Because of these enormous tax concessions to the rich, the government’s direct tax revenues (meaning the taxes on incomes) are obviously going to be low. The government is compensating for this loss in revenues by increasing its reliance on indirect taxes (which are imposed on goods and services). That is the reason for the huge rise in petrol and diesel prices in recent times – the government has increased excise duties on them to such an extent that taxes on them constitute more than 50% of their retail price.

Direct taxes fall directly on the rich; while indirect taxes fall on all, both rich and poor. An equitable system of taxation taxes individuals and corporations according to their ability to pay, which in practice means that in such a system, the government collects its tax revenue more from direct taxes than indirect taxes. The Economic Survey 2017–18 admitted that India has a much lower proportion of direct taxes in its total tax revenue as compared to other emerging market economies. In most developed and developing countries, the direct tax revenue as a percentage of total revenue is between 55% to 65%; for Europe, this proportion is about 70%. But in India, the ratio is the exact opposite: for every Rs 100 collected by the government as tax revenue, only around Rs 30 comes from direct taxes.[6]

b) Loan Waivers

During the first six years of the Modi Government (that is, 2014–2020), and three quarters of fiscal 2020–21, public sector banks have waived loans given to big corporate houses of at least Rs 8.9 lakh crore.[7]

This figure does not include the interest accruing on these loans; including that, the loss would be four times this amount.[8]

Additionally, public sector banks have restructured loans of the ‘high and mighty’—a roundabout way of writing off loans—probably of the order of several lakh crore rupees (the actual amount is not known).[9]

Even after all these write-offs, the total non-performing assets (a euphemism for bad loans) of public sector banks had gone up to Rs 7.57 lakh crore as of 31 December 2020.[10] Most of these are loans to big corporate houses. Considering the nature of the ruling regime, the great majority of these are also going to be written off very soon.

Adding up all these amounts, it means that since it came to power in 2014, the Modi Government has written off, or is in the process of writing off, at least Rs 25 lakh crore of loans to big corporate houses. (This estimate assumes that write-offs in the name of loan restructuring are as much as the loan write-offs. This figure does not include interest accruing on these loans; including that, the figure may be much more than this.)

c) Other Transfers of Public Funds to Private Coffers

The Modi Government has handed over control of the country’s mineral wealth and resources to private corporations in return for negligible royalty payments, transferred ownership of profitable public sector corporations to foreign and Indian private business houses at throwaway prices, given direct subsidies to private corporations in the name of ‘public–private–partnership’ for infrastructural projects, and so on. These transfers of public wealth to private coffers have resulted in enormous losses to the public exchequer.

To give just one example of this open dacoity on public wealth, the Modi Government has indulged in an accelerated privatisation of public sector enterprises during the past six years. During its seven years in power, it has sold off government stake in public sector companies to earn Rs 3.6 lakh crore.[11] For the year 2021–22, it has set a target of earning an ambitious Rs 1.75 lakh crore from disinvestment. For achieving these targets, it plans to sell off some of the best performing public sector companies, including IOC, NTPC, Oil India, GAIL, NALCO, BPCL, EIL, BEML, etc., and also privatise public sector banks and insurance companies. While mainstream economists and a docile media have hailed these disinvestment targets, what no one mentions is that this privatisation is actually causing a huge loss to the government. Thus, for instance, the government has begun the process of selling of its entire 53 percent stake in Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd (BPCL)—a vertically integrated oil and gas company with investments in refining, marketing, upstream and gas business. The government, according to news reports, is hoping to earn Rs 40,000 crore from the sale. According to the Public Sector Officers’ Association, the present worth of BPCL’s physical assets is Rs 9 lakh crore, which would mean that the government’s stake is worth at least Rs 5.2 lakh crore (even without adding a premium for handing over control of the company)—more than 13 times what the government expects to earn from its sale![12]

This is the case with each and every public sector unit being privatised by the Government—each of these public assets has been sold at heavily discounted prices to foreign and Indian private corporations. So, when the Government claims that it is hoping to earn Rs 1.75 lakh crore in disinvestment income in 2021–22, actually in this process the (notional) loss to the public exchequer is going to be of the order of 10–20 lakh crore rupees.

d) Refusal to Act against Black Money

One of the important promises made by the Narendra Modi during the 2014 elections was that if voted to power, he would take action to bring back the black money stashed abroad by the corrupt, and deposit Rs 15 lakh in the account of every citizen.

But after winning the elections, the Prime Minister Modi made a complete U-turn on the issue. In fact, soon after coming to power, the Modi Government went to the extent of refusing to divulge the names of foreign account holders in the Supreme Court. Commenting on the application moved by the attorney general on behalf of the government in the Supreme Court, senior advocate Ram Jethmalani, who was the petitioner in the case, stated, “The government has made an application which should have been filed by the criminals. I am amazed.”[13]

In February 2015, Indian Express released the list of 1,195 Indian account holders and their balances for the year 2006–07 in HSBC’s Geneva branch, in what has become infamous as ‘Swiss Leaks’. The names included several prominent Indian businessmen—Mukesh Ambani, Anil Ambani, Anand Chand Burman, Rajan Nanda, Yashovardhan Birla, Chandru Lachhmandas Raheja and Dattaraj Salgaocar—and the top diamond traders of the country—Russell Mehta, Anoop Mehta, Saunak Parikh, Chetan Mehta, Govindbhai Kakadia and Kunal Shah. The Modi Government simply sat over the names. HSBC whistleblower Herve Falciani, talking to the media in November 2015, said the Indian government “had not used information on those illegally stashing away black money in foreign bank accounts, and still millions of crores were flowing out”.[14]

Again, in 2016, 11 million documents held by the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca were leaked by an anonymous source, and obtained and made public by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The documents show the myriad ways in which the world’s rich exploit secretive tax havens to hide their wealth. The leak, that became known the world over as the Panama Papers scandal, contained the names of 500 Indians who have links to offshore firms, including politicians, businessmen and films stars. The names include those of Amitabh Bachchan, Aishwarya Rai, DLF owner K.P. Singh, Garware family, Nira Radia, Harish Salve, and Gautam Adani’s elder brother Vinod Adani, to name a few.[15] Once again, the government did nothing.

According to one newsreport, the biggest case of black money parked in offshore havens being investigated by Indian authorities is that of business tycoon Gautam Adani.[16] Considering the close relations between Adani and Modi, and the fact that Adani grew from being a small time businessman to one of India’s biggest business tycoons during just the decade when Modi was Chief Minister of Gujarat, and to becoming the second richest person in India during Modi’s Prime Ministership, it is obvious that Adani will never be prosecuted.

The Modi Government is the most pro-corporate, pro-rich government to have come to power at the Centre since independence. It is a government by the rich, for the rich. It is the country’s biggest corporate houses who had financed Modi’s election victory in 2014, and have been backing him ever since;[17] Modi has reposed the trust they bestowed on him by running the government solely for their profit maximisation. Even during the pandemic, while the government refused to increase its social sector expenditures and provide a decent relief package to the people to alleviate the enormous distress caused by the lockdown, it allowed the corporate houses to continue their plunder of the country’s wealth. Consequently, even as the economy is set to contract by a record –8% in 2020–21, the number of billionaires in the country went up by 40, taking the number of billionaires in the country to 177, according to the Hurun Global Rich List 2021.[18]

The government’s unwillingness to act against those who have illegally stashed huge sums of money abroad, its refusal to take firm steps to curb illicit flows of black money, has resulted in huge loss in tax revenues to the government.

Consequence: Low Government Revenues

In every capitalist country in the world, including the developed capitalist countries, while their governments essentially run the economy for the profiteering of the rich, they also collect significant amount of taxes from them and spend it on providing education, healthcare and other welfare services for their people. Most developed countries have a very elaborate social security network for their citizens, including unemployment allowance, universal health coverage, free school education and free or cheap university education, old age pension, maternity benefits, disability benefits, family allowance such as child care allowance, allowances for those too poor to make a living, and much more.

In contrast, in India, the tax and non-tax concessions and transfers to the corporate houses have reached such mindboggling levels under the Modi Government that India’s total government revenue as percentage of GDP is not only far below the developed countries, it is also way below the other Emerging Market Economies. In 2019, general government revenue as percentage of GDP averaged 46.5% for the 19 countries of the Eurozone area, going up to above 50% for countries like Belgium, France, Denmark and Finland. It was 29.1% for South Africa, 33.9% for Argentina and 31.9% for Brazil; the average for Emerging Market and Middle-Income Economies was 27.1%. For India, however, general government revenue (Centre + States combined) in 2019 was only 19.7% of GDP.[19]

Part II: An Alternate, Pro-People Budget: Some Suggestions

If the government partially withdraws some of the concessions / subsidies / transfers of public wealth being given to the rich, and imposes some additional taxes on them, it can raise enough additional revenues to finance a big hike in its social sector expenditures. Here are a few examples of the measures the government can take.

i) Reducing the Huge Tax Concessions Given to the Rich

The Modi Government has been giving at least Rs 6 lakh crore in tax concessions to the rich every year. Even if the government reduces these concessions by 75 percent, it will result in an increase in the government’s annual tax revenues by Rs 4.5 lakh crore. (This figure excludes the possible increase in revenues if the government takes action to curb illicit flows of money.)

ii) Reducing the Huge Transfers of Public Funds to the Rich

The government is writing off bank loans given to the rich to the tune of a few lakh crore rupees every year; it is transferring ownership of public sector corporations to the private sector at throw-away prices; it is allowing private sector corporations to exploit our country’s mineral resources and earn huge profits in return for negligible royalty payments; it is giving corporate houses enormous subsidies on their investments in the infrastructure sector; and so on. Even if it partially withdraws these concessions, it will increase government revenues by several lakh crore rupees every year. For our calculations, let us conservatively assume this increase to be Rs 3 lakh crore every year.

iii) Imposition of Wealth Tax on the Richest 1 percent

There is nothing very anomalous about a wealth tax. In fact, inequality in the world has grown to such extremes that even the annual jamboree of the world’s super rich held at Davos, Switzerland has expressed concern, and ‘establishment’ economists across the world have been demanding imposition of wealth taxes on the rich to reduce it. Wealth taxes exist in several European countries. [20]

According to an estimate made by Credit Suisse in 2019, the richest one percent in India own 42.5 percent of the total wealth of the country, which works out to $5361 billion or Rs 380.631 lakh crore.[21] Imposition of a low 2 percent wealth tax on this would earn the government Rs 7.6 lakh crore in revenue. (Incidentally, during the 2020 USA Presidential elections, both Warren and Sanders had proposed a minimum wealth tax of 2 percent, rising to 6 / 8 percent for those with fortunes over $1 billion).

iv) Imposition of Inheritance Tax on the Richest 1 percent

This tax is also perfectly in sync with the ideology of capitalism. While supporters of capitalism argue that the rich are so because of their special qualities like ‘innovativeness’ and ‘entrepreneurship’, there is no reason why their children should be in possession of all their wealth; and so it is perfectly justified if governments impose a substantial inheritance tax on the very rich. Several developed countries had a large inheritance tax till the 1980s; during the past three decades, due to the rise of neoliberalism, many have either removed or reduced it. Recently, an OECD report called for (re-)introduction of inheritance tax as a way of reducing wealth inequality. Inheritance tax rate in France continues to be 45 percent, and in South Korea and Japan is 50 percent.[22]

For India, if the government imposes a modest inheritance tax rate of 33 percent on the richest 1 percent people in the country, then, assuming that about 5 per cent of the wealth of these top 1 per cent gets bequeathed every year to their children or other legatees, the government would earn 380.6 lakh crore x .05 x .33 = Rs 6.28 lakh crore as inheritance tax revenue every year.

v) Total

These four suggestions given above would fetch the government an additional (4.5 + 3 + 7.6 + 6.3 =) Rs 21.4 lakh crore in revenue. That would send out budgetary outlay zooming from Rs 34.8 lakh crore in 2021-22 BE to Rs 56.2 lakh crore.

Financing a Huge Increase in Social Sector Expenditures is Dooable

Assuming that the government’s social sector expenditures (Centre + States combined) in 2021–22 are around 7% of GDP, that would amount to Rs 15.6 lakh crore. This means that if the Centre reduces some of the enormous subsidies it is giving to the rich and implements the suggestions given above, the resulting increase in Centre’s revenues of Rs 21.4 lakh crore would be enough to more than double the total social sector expenditures of both the Centre and States combined.

To be more specific, this increase in government revenues would be more than enough to finance:

i) An increase in total educational spending (Centre + States) to 6% of GDP, from the present 3% of GDP. Additional spending required = Rs 6.7 lakh crore.

ii) An increase in total health spending (Centre + States) to 3% of GDP, from the present 1.5% of GDP. Additional spending required = Rs 3.3 lakh crore.

iii) Implement a universal pension scheme and provide all the old people in the country a (non-contributory) monthly pension of Rs 2,000 per month. There are an estimated 12 crore people in the country above the age of 60. So cost to government = 12 crore x 2000 x12 = Rs 2.9 lakh crore.

iv) Implement a universal PDS, and provide all citizens 35 kg of rice /wheat and 5 kg of millets (at Rs 3/2/1 per kg respectively) and 2 kg of pulses and 1 kg of edible oil (at subsidy of Rs 50 per kg for both) per household per month. Additional spending required = Rs 1.70 lakh crore (for 2021–22).

v) Triple government expenditure on nutrition schemes (including anganwadi services, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana and Mid-day Meal scheme). Additional spending required = Rs 70,000 crore.

vi) Genuinely implement MGNREGA. Additional spending required = Rs 1.3 lakh crore.

vii) Double government spending on agriculture. Additional spending required = Rs 1.4 lakh crore.

viii) Total = 6.7 + 3.3 + 2.9 + 1.7 + 0.7 + 1.3 + 1.4 = Rs 18 lakh crore.

After implementing all the above suggestions, the government would still have Rs 3.4 lakh crore to finance many more such proposals.

In demanding of the government that it implement the above suggestions, we are only actually asking the government to implement the dreams of our country’s founding fathers, which are encapsulated in the Directive Principles of the Constitution. They call upon the State to strive to:

- provide good quality education, health care and nutrition to all citizens, and provide all citizens meaningful work and a living wage that ensures them a decent standard of life and full enjoyment of leisure.

References

- “Government’s Social Sector Spending “woefully” Below Peers: RBI”, April 11, 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com.

- “India’s Covid-19 pandemic fiscal cost lowest among major nations: Report”, 19 June 2020, https://www.business-standard.com.

- Our estimate. Budget documents reveal that in 2014–15 and 2015–16, the Modi Government gave tax exemptions to the country’s uber rich totalling Rs 11 lakh crore. In 2016–17, the government changed its methodology of making this calculation to show a much lowered figure—we have calculated that actual tax concession was the same as the previous year, Rs 5.5 lakh crore. In the subsequent years, the government stopped making a full estimate of these tax concessions. Considering the overall attitude of the government towards giving subsidies to the rich, we can safely estimate that tax concessions for the subsequent years must be at least at the same level as the first three years, if not more. So, total tax concessions for 7 years = 5.5 x 7 = Rs 38.5 lakh crore. For more on this, see our article: Neeraj Jain, “Pandering to Dictates of Global Finance”, Janata, 19 February 2017, http://www.janataweekly.org.

- “Two Crore Indians File Returns but Pay Zero Income Tax”, 23 October 2018, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com.

- Rajul Awasthi, “India’s ‘Billionaire Raj’ Era: Time to Reform Personal Income Tax”, September 20, 2017, https://thewire.in.

- “Of Bold Strokes and Fine Prints: Analysis of Union Budget 2015–16”, Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability, March 2015, pp. 18–19, http://www.cbgaindia.org. See also Economic Survey 2017-18.

- According to a report in Business Today, public sector loan write-offs during the first four years of the Modi Government total Rs 3.08 lakh crore, of which loans pertaining to agriculture total only Rs 27,000 crore: “Bad Loans Worth Rs 80,893 Crore Written Off by Banks Till September Quarter”, 3 December 2019, https://www.businesstoday.in. See also: Prasanna Mohanty, “Reality Check: RBI Acts Penny-Wise-Pound-Foolish in Dealing with NPA Crisis”, 6 November 2019, https://www.businesstoday.in. For the years 2018–19, 2019–20 and first three quarters of fiscal 2020–21, figures taken from: “Banks Wrote-Off Rs 1.15 Lakh Crore In 9 Months Of FY21, Says Anurag Thakur”, 9 March 2021, https://www.bloombergquint.com.

- Sucheta Dalal, “Loan Write Offs Is the ‘Biggest Scandal of the Century’”, 9 May 2016, https://www.moneylife.in.

- For more on this, see our booklet, “ Is the Government Really Poor?”, Lokayat publication, Pune, 2018, http://lokayat.org.in.

- “Banks Wrote-Off Rs 1.15 Lakh Crore In 9 Months Of FY21, Says Anurag Thakur”, 9 March 2021, https://www.bloombergquint.com.

- “Government Raises Rs 2.79 Lakh Crore Through Divestment in Last 5 Years”, 3 December 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com. For the years 2019–20 and 2020–21, figures taken from 2021 budget documents.

- “Government All Set to Disinvest ‘Revenue Churner’ BPCL; Here’s What it Means”, 25 November 2020, https://www.dnaindia.com; Piyush Pandey “Notional Loss in BPCL Sale Plan at Rs 4.5 lakh cr.”, 10 December 2019, https://www.thehindu.com.

- Dhananjay Mahapatra, “Now, Modi Govt Too Refuses to Name Foreign Bank Account Holders”, October 18, 2014, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com.

- Ashish Mehta, “Surgical Strike? This was Aspirin for Cancer”, November 9, 2016, http://www.governancenow.com; Ritu Sarin, “Exclusive: HSBC Indian List Just Doubled to 1195 Names. Balance: Rs 25420 Cr”, February 9, 2015, http://indianexpress.com.

- “Panama Papers: From Amitabh Bachchan to Adani’s Brother, Names of 500 Indians Leaked”, April 4, 2016, http://www.business-standard.com; “Exclusive: Panamagate India”, April 8, 2016, http://www.theindianeye.net.

- “What Exactly is Black Money, and Can Demonetisation Make a Dent in It?” November 12, 2016, http://www.thenewsminute.com.

- See for example: Siddharth Varadarajan, “The Cult of Cronyism”, March 31, 2014, http://newsclick.in.

- “India adds 40 billionaires in pandemic year; Adani, Ambani see rise in wealth: Report”, 2 March 2021, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com.

- “Fiscal Monitor – April 2020”, Statistical Appendix, https://www.imf.org.

- Martin Hart-Landsberg, “A Wealth Tax: Because that’s Where the Money Is”, 19 November 2019, https://mronline.org.

- Global Wealth Databook 2019, October 2019, Credit Suisse, Switzerland.

- “Use Inheritance Tax to Tackle Inequality of Wealth, Says OECD”, 12 April 2018, https://www.theguardian.com; “Inheritance Tax: A Hated Tax but a Fair One”, 23 November 2017, https://www.economist.com; Michael Förster et al., “Trends in Top Incomes and Their Taxation in OECD Countries”, May 2014, https://www.researchgate.net.

Neeraj Jain is a Btech in Electrical Engineering. He is a social activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. This article was earlier published in Janata.

GET COUNTERCURRENTS DAILY NEWSLETTER STRAIGHT TO YOUR INBOX